Welcome Back to Earth

President Nixon and a large entourage left Washington on the evening of July 22 to begin the trip to the Apollo H splashdown and then to undertake the president’s round-the-world diplomatic mission. After spending the night in San Francisco, on July 23 they flew to Johnston Island, a small atoll 750 miles west of Hawaii. During that flight, Nixon, NASA Administrator Paine, and national security adviser Kissinger spent some time discussing the president’s desire to increase international participation in the U. S. space program; Paine remembers that “we made a great deal of progress in laying out the plan for international cooperation.”34 Borman was also aboard Air Force One, and met separately with the president and Kissinger, also to discuss international space cooperation.

The president’s party arrived on Johnston Island at 5:00 p. m. local time. Those of the group that would view the Apollo H splashdown then boarded helicopters for the hour and a half trip to the aircraft carrier Arlington, where they would spend the evening. As he had earlier met with Ehrlichman to plan his trip to meet the returning Apollo 11 astronauts, President Nixon had attempted to stage manage his trip to the splash down. He recognized that Secretary of State William Rogers and Kissinger would have to be part of the diplomatic trip, but he did not want them to accompany him to the recovery; instead, Nixon declared, they would stay on Johnston Island awaiting his return. Nixon did not want to share the event with

|

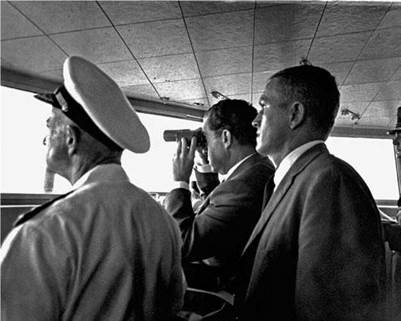

President Nixon, Apollo 8 astronaut Frank Borman (right) and Admiral John McCain (left) watch as the recovery carrier Hornet approaches the Apollo 11 capsule after it splashed down in the Pacific Ocean on July 24, 1969. (NASA photograph 6900598) |

a large entourage; his presence as the crew returned from the Moon was “to be his triumph, not theirs" Nixon told Ehrlichman that “no staff— no Dr. [Doctor]—only two SS [Secret Service]—no press pool—nobody” was to ride on his helicopter to the recovery carrier. Ehrlichman described these directives as an example of the “forlorn and impossible wishing game he liked so well.” He added “as he knew it would, Nixon’s entourage at the splashdown included the full complement of bodyguards, a vast press contingent, the President’s doctor, Haldeman, Haldeman’s aide, and, of course, both Rogers and Kissinger.”35

Haldeman in his diary described in vivid detail both the trip from the Arlington to the smaller recovery carrier Hornet to view the splashdown and the event itself:

Up at 4:00 for 4:40 departure. It was beautiful on the flight deck, absolutely dark, millions of stars, plus the antenna lights on the ship. Borman said it looked more like the sky on the back side of the moon than any he had ever seen on earth. Helicopter left in the dark and flew over the ocean to the Hornet. Landed and went through quick briefings on the decontamination setup and the recovery plan. Then waited on the bridge for the capsule to appear.

It did, in spectacular fashion. We saw the fireball (like a meteor with a tail) rise from the horizon and arch through the sky, turning into a red ball,

then disappearing. Waited on the bridge for an hour or so until we could see the helicopters over the capsule and raft in the sea. We steamed toward them. Watched the pickup, first through binoculars, then with naked eye. P [the president] was exuberant, really cranked up, like a little kid. Watched everything, soaked it all up.

Then the pickup helicopter landed on deck. P ordered band to play “Columbia the Gem of the Ocean.” . . . Then down to the hangar deck for P chat with the astronauts in quarantine chamber. Great show. He was very excited, personal, perfect approach. Then prayer and “Star Spangled Banner.” Then “Ruffles and Flourishes” and “Hail to the Chief,” and we left.36

The Apollo H command module Columbia splashed down on target at 5:51 a. m. local time (12:51 p. m. EDT) on July 24, 13 miles from the Hornet. After donning their “biological containment garments,” Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins were helped from their spacecraft into a raft, then lifted into a waiting helicopter. By now, the Hornet was only a quarter of a mile away, and the helicopter carrying the Apollo H crew landed on its deck at 6:57 local time.

The astronauts had an hour before interacting with the president, first undergoing a quick medical examination, then taking a shower and changing into comfortable clothing. Armstrong later reflected “there were the Nixon ceremonial activities to attend to. We needed to do that and get it behind us so we could celebrate.” Collins added that after showering and shaving, “we were looking for something to do, and it’s not long in coming.” The crew was summoned to the end of the quarantine facility and “parting the curtains we see that the hangar deck has arranged for some sort of ceremony—the first of many, I would guess.” After the band played Ruffles and Flourishes, “in marches none other than President Nixon, looking very fit and relaxed as he stands by a microphone just outside our window.”As he spoke with the crew, Nixon demonstrated his lack of facility with small talk, attempting to joke that his conversation with the crew while they were on the Moon was a collect call, pointing out Frank Borman standing nearby, and asking whether the crew knew the results of the baseball All Star game and whether they were fans of the American or National League. One of Nixon’s biographers suggested that his conversation “set some sort of record for inappropriateness.” He told the astronauts that he had spoken to their wives—“three of the greatest ladies and most courageous ladies in the whole world today”—and had invited them to a dinner on August 13. He asked the crew “Will you come?” Demonstrating his “penchant for hyperbole and weakness for gross exaggeration,” Nixon “came out with the all-time Nixonism,” telling the crew that “this is the greatest week in the history of the world since the Creation, because as a result of what happened in this week, the world is bigger, infinitely” and “as a result of what you have done, the world has never been closer together before.”37

Shortly after 9:00 a. m., President Nixon and his party boarded their helicopters for the return trip to Johnston Island; by early that afternoon, they were on their way to Guam, the first stop in a tour that would bring

|

President Nixon jokes with the Apollo 11 crew in their mobile quarantine facility. (Photo courtesy of Milt Putnam, the Navy photographer who recorded the recovery of the Apollo 8, 10, and 11 crews after their return from the Moon.38) |

Nixon to the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, India, Pakistan, Romania, and the United Kingdom before returning to Washington on August 3. At each stop on the journey, Nixon evoked “the spirit of Apollo 11.” For example, when he landed in Manila, the president said “as we think of that great venture into space, as we think of the first man setting foot on the moon, we realize the meaning that that has, clearly apart from the technical achievement, we realize that if man can reach the moon, that we can bring peace to the earth. And that should be the great lesson of that great space journey for all of us.” In Romania, Nixon added “mankind has landed on the moon. We have established a foothold in outer space.” He added “but there are goals that we have not reached here on earth. We are still building a just peace in the world. This is a work that requires the same cooperation and patience and perseverance from men of good will that it took to launch that vehicle to the moon. I believe that if human beings can reach the moon, human beings can reach an understanding with each other on the earth.” As had been planned from the start of the Nixon administration, and indeed from 1961 as President Kennedy had laid out his rationale for sending Americans to the Moon, the Apollo 11 triumph was used by President Nixon as a powerful tool in Earth-bound diplomacy.39

Missing in Richard Nixon’s communications during the Apollo 11 mission and his subsequent world tour was any mention of John F. Kennedy. However, some in NASA did recognize President Kennedy’s role. As the Apollo 11 spacecraft splashed down in the Pacific Ocean, one of the video screens in the front of the mission control room at NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston had displayed Kennedy’s 1961 challenge, while another screen noted simply: “Task Accomplished.”40

On the evening of August 10, 21 days after leaving the surface of the Moon, the Apollo 11 crew members were released from their Houston quarantine. Early on the morning of August 13 they left Houston on what promised to be an exhausting day. The crew and their wives and children were flown by Air Force Two to New York City for a ticker-tape parade. According to Armstrong’s biographer, “not even the revelry at the end of World War II or the parade for Lindbergh in 1927 matched in size” the crowd watching the crew’s parade through Manhattan; one estimate of the turnout was 4 million people. Then on to Chicago, where the crowds were “even wilder.” Finally the astronauts arrived in Los Angeles for the huge dinner celebrating their mission.

Richard Nixon acted as master of ceremonies for the evening. The assemblage included representatives of 83 countries, governors from 44 states, 14 members of the president’s cabinet (“More members of the Cabinet than are usually present at a Cabinet meeting,” joked Nixon), the chief justice of the Supreme Court, 50 members of Congress, a bevy of Hollywood stars, NASA officials and astronauts, aerospace industry executives, and the man who Nixon had defeated in the contest to be president, former Vice President Hubert Humphrey. At the culmination of the evening, Vice President Spiro Agnew presented the Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian award, to each of the Apollo 11 crew members. Then the astronauts spoke. Michael Collins said “here stands one proud American, proud to be a member of the Apollo team, proud to be a citizen of the United States of America which nearly a decade ago said that it would land two men on the moon and then did so, showing along the way, to the world, both the triumphs and the tragedies—and proud to be an inhabitant of this most magnificent planet.” Buzz Aldrin added, “There are footprints on the moon. Those footprints belong to each and every one of you, to all of mankind, and they are there because of the blood, the sweat, and the tears of millions of people. These footprints are a symbol of the true human spirit.” Neil Armstrong hoped that “this is the beginning of a new era, the beginning of an era when man understands the universe around him, and the beginning of the era when man understands himself.” President Nixon closed the evening, saying “It has been my privilege in the White House, and also in other world capitals, to propose toasts to many distinguished people, to emperors, to kings, to presidents, to prime ministers. . . Tonight, this is the highest privilege I could have, to propose a toast to America’s astronauts.” Reflecting on the event the next day, Haldeman suggested that the “dinner was a truly smashing success. . . Highly emotional and patriotic evening that completely succeeded in meeting all the P’s objectives. Well worth all the work.”41