The author had the good fortune to be present at the Apollo 11 launch

Even before Apollo 11 lifted off, the crew and mission planners back in Houston had agreed that if all was going well, Armstrong and Aldrin would skip their scheduled rest period and start their extra-vehicular activity on the lunar surface as soon as they were ready. Within an hour after landing, Armstrong received permission to begin the crew’s moonwalk at approximately 9:00 p. m. Informed of this change in plans, President Nixon arrived in the White House office area just before 9:00 p. m., only to be advised that preparations were running more slowly than expected. Almost two hours later, Armstrong stood on the outside of the lunar module, ready to climb down to the surface of the Moon. A worldwide audience watched his ghost-like image descend the module’s ladder; then, Armstrong announced that he was ready to step off the lunar module. He took his historic “one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind” at 10:56 p. m. on July 20, 1969. (In the excitement of the moment, Armstrong did not fully articulate the “a” in his statement, although some later acoustic analyses suggested that he had indeed included the article in what he said. In retrospect, Armstrong himself was typically enigmatic, saying to his biographer “I would hope that history would grant me leeway for dropping the syllable and understand that it was certainly intended, even if it wasn’t said— and it actually might have been.28) Aldrin soon followed Armstrong to the lunar surface, stepping off the lunar module at 11:15 p. m.

|

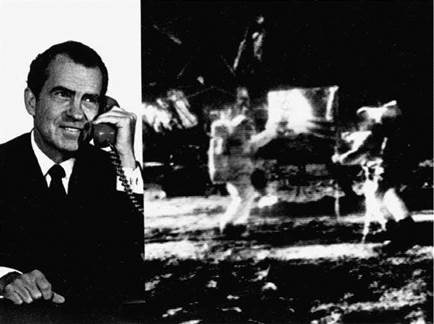

President Richard Nixon talks to Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on the surface of the Moon, July 20, 1969. (NASA photograph GPN-2000-1672) |

President Nixon watched the historic first steps on the Moon on a small television in his private office in the White House, next to the more formal Oval Office. Borman and Haldeman were with him. According to Haldeman, Nixon was “very excited by the whole thing. Was fascinated by the moon walk.” The president then went into the Oval Office, where from 11:45 to 11:50 p. m., in the dispassionate words of the his official “Daily Diary,” he “held an interplanetary conversation with the Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin Aldrin on the Moon.” The conversation was shown on split-screen television and seen live around most of the world, but not in the Soviet Union.29

Nixon had available to him for this conversation two different versions of prepared remarks, one written by lead speechwriter Ray Price and the other by William Safire, but he used neither version. Borman says that he and Safire composed the actual comments, while Haldeman suggests that Nixon “wrote his own remarks.” Safire recalls that he was watching the preparations for the moonwalk from his home and was struck by the idea that the president should work the theme of “tranquility” into his remarks, given that Eagle had landed on the Moon’s Sea of Tranquility. Safire called the White House and asked that his thought be relayed to the president as he prepared for his Apollo 11 phone call. Whatever the source of the rhetoric, what the president said reflected the themes—pride, power, and peace—that Nixon had from the start of his preparations wanted to associate with the lunar landing. Nixon told Armstrong and Aldrin as they stood beside the American flag on the lunar surface:

Hello Neil and Buzz, I am talking to you by telephone from the Oval Room at the White House, and this certainly has to be the most historic telephone call ever made from the White House.

I just can’t tell you how proud we all are of what you have done. For every American this has to be the proudest day of our lives, and for people all over the world I am sure that they, too, join with Americans in recognizing what an immense feat this is.

Because of what you have done the heavens have become a part of man’s world, and as you talk to us from the Sea of Tranquility, it inspires us to redouble our efforts to bring peace and tranquility to earth.

For one priceless moment in the whole history of man all the people on this earth are truly one—one in their pride in what you have done and one in our prayers that you will return safely to earth.

Armstrong replied to the president: “It is a great honor and privilege for us to be here representing not only the United States, but men of peaceable nations, men with an interest and a curiosity, and men with a vision for the future.”30

The president’s phone call came as a complete surprise to Aldrin, who found it “awkward” and decided not to respond. Armstrong had been alerted before launch that there might be a “special communication” while the two astronauts were on the Moon, but he was not told that it would be

President Nixon on the line. Armstrong did not share this “heads up” with Aldrin. Armstrong later suggested that “If I’d known it was going to be the president, I might of tried to conjure up some appropriate statement.” Armstrong’s not sharing his advance information with Aldrin was typical of the relationship between the members of the Apollo 11 crew, described by Collins as “amiable strangers.”31

On the morning of July 21, the front page of the The New York Times in a 96-point banner headline announced “Men Walk on Moon.” (In the early edition of the paper, sent to press before Aldrin had joined Armstrong on the lunar surface, the headline had been singular—“Man Walks on Moon.”) The newspaper also included on its front page the poem Archibald MacLeish had composed to commemorate the occasion, titled “Voyage to the Moon.”32

Eagle with Armstrong and Aldrin and 49 pounds of lunar samples aboard lifted off of the Moon’s surface at 1:54 p. m. on July 21, first to rendezvous in lunar orbit with Columbia, where Collins had been patiently waiting, and then to head back for an early morning splashdown in the South Pacific on July 24. The crew had little to do on the return trip, and reverted to characteristics that Borman had noted in his July 14 memo to Nixon. Armstrong asked mission control for a report on the stock market, and Collins rummaged around the various storage areas of the spacecraft, hoping, with tongue in cheek, that someone had surreptitiously smuggled aboard a small supply of cognac.33