Two Last Flights for SpaceShipOne

Scaled Composites received about $25 million from Paul Allen for twenty tasks that Burt Rutan had specifically outlined, which covered

building SpaceShipOne all the way through competing with it. “Task 21 was that we would fly SpaceShipOne every Tuesday for five months, reasoning that if we did that you could then make with confidence a commercial business plan,” Rutan said.

But Task 21 wasn’t funded. Rutan figured that once he got the data on the real costs of flying SpaceShipOne, he would then approach Allen. “That would be the opportunity for Paul and me and both of our friends to be astronauts,” Rutan explained. “If you just count only the passengers, you’ve got forty-four people. So, maybe twenty of my friends could be astronauts and twenty of his friends could be astronauts. That would be kind of cool. That was the plan. But something got in the way of the plan. I underestimated the impact of SpaceShipOne on the media and the public, and I underestimated its effect on historians.”

Shortly after Melvill flew SpaceShipOne into space the first time, Rutan received a letter from Valerie Neal, the curator of post-Apollo human spaceflight for the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum. “It was clear to all of us right away once Mike Melvill had made the first flight in June that this was a remarkable achievement, whether or not it won the Ansar і X Prize,” Neal said.

“We think that SpaceShipOne either itself may prove to be the pivotal craft that leads to a commercial spaceflight space-tourism industry, or it’s the leading edge of that. You know there are enough developments going on right now. It looks as if this is the cusp of a new revolution in spaceflight.”

So, the National Air and Space Museum expressed its interest in acquiring SpaceShipOne to join it with other remarkable vehicles in the Milestones of Flight gallery, which includes the original 1903 Wright Flyer, Spirit of St. Louis, and the Bell X-l that broke the sound barrier, Glamorous Glennis. But the National Air and

Ґ л

|

Fig. 10.11. When SpaceShipOne made it first spaceflight on June 21,2004, the National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution immediately recognized the significance of the event. By becoming the first nongovernmental, privately funded vehicle to reach space, SpaceShipOne earned a place in the Milestones of Flight gallery with the Spirit of St. Louis, Bell X-1, 1903 Wright Flyer, and Apollo 11 command module Columbia.

Courtesy of Virgin Galactic

Ґ Л

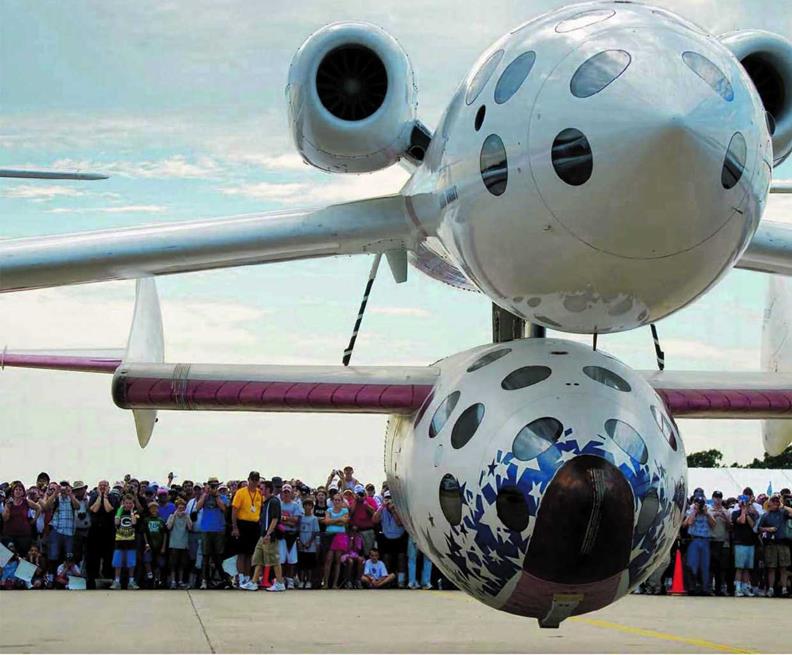

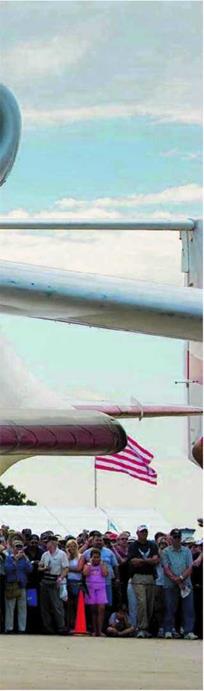

Fig. 10.10. On June 27, 2005, Burt and Tonya Rutan, in SpaceShipOne, and Mike and Sally Melvill, in White Knight, landed at Oshkosh, Wisconsin, for the Experimental Aircraft Association’s (EAA) 2005 AirVenture. An active EAA member, Burt Rutan introduced the VariViggen, the first aircraft he designed and built, at the 1972 AirVenture. Now he and Melvill, also a longtime EAA member, gave a special showing of SpaceShipOne and White Knight to many of their closest supporters. Tyson V. Rininger

V______________________________ J

Space Museum didn’t realize the extent to which Allen was involved. Rutan said that he would have to bring Allen into the dialog as well.

“So,” Neal recalled, “it was right at the end of November or early December when Allen and Rutan both said, ‘Yeah, we’re really interested

in donating this to the museum. Come on out and let’s talk and let’s have a look at it together.’”

Rutan had to face a tough decision. He explained, “When we got that request, Paul Allen called and said, ‘Listen, I don’t want you to fly it anymore. Just get the X Prize. Two more flights and

|

|

Ґ

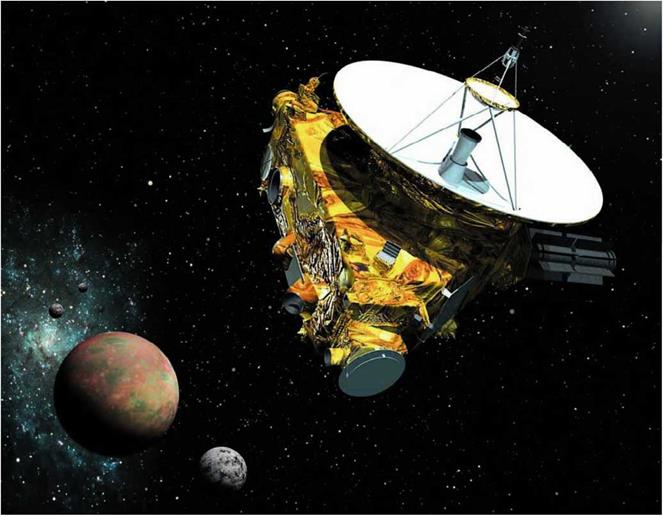

Fig. 10.12. Carrying a small piece of SpaceShipOne, the space probe New Horizons, launched in 2006, races to the edge of the Solar System. The first mission ever to the dwarf planet Pluto, it will arrive in 2015. NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory-Southwest Research Institute

V______________________________________________________________________________

that’s it.’ We had three or four motors, so we could have easily flown one more flight. My first thought was to fight with him. I said, ‘No, you’ve got to prove a business plan. If this is going to go on to the next step, you got to do this.’ And then I realized that he really was right.”

Preserving the legacy was more important.

Valerie Neal recalled, “What I had asked Rutan to do before he delivered it to us was to return it to its June configuration. After that June flight, before the X Prize flights, quite a number of decals were added to it, and the Virgin Galactic logo was added to it. And the appearance was considerably different.”

Even the dent in the engine fairing from that flight was put back. That’s how seriously Scaled Composites took her request. So, right after SpaceShipOne was hung in the museum, the damage drew some quick notice. “The director of the museum came in and said, ‘I hope we didn’t do that last night.’ And I said, ‘No, no, it came that way,’” Neal said.

However, even before being transferred to the museum, Rutan wanted to fly White Knight and SpaceShipOne to Oshkosh. He wanted to do something special for the Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA), which had stood by him from the time of his very first aircraft. With Mike Melvill behind the stick of White Knight and SpaceShipOne attached below, he flew from Mojave but stopped right before reaching the air show in Madison, Wisconsin, to pick up some very important passengers. Burt Rutan and his wife, Tonya, climbed into SpaceShipOne, while Sally Melvill joined her husband in White Knight.

They touched down at Oshkosh on June 27, 2005. “It was very emotional because it was like a homecoming for the triumphant soldier,” said Tom Poberezny, president of EAA. “And here was Burt coming home to an audience that truly appreciated what he did because they’ve grown up with him. They’ve appreciated every design innovation he has ever done, his successes, his failures, his trials, his tribulations.”

Figure 10.10 shows the EAA crowd gathered around SpaceShipOne andWhite Knight.

When the air show ended, Melvill took off with a small crew to head for Dulles Airport in Washington, D. C., after first stopping over in Dayton, Ohio, the hometown of the Wright brothers. But the adventure was far from over. White Knight doesn’t have very long legs. Its range is only about 500 miles (800 kilometers). When it reached

Dulles Airport, someone must have noticed White Knight carrying a missile-like object. “So, they turned us around and drove us away right in the middle of the approach,” Mike Melvill said.

“I said, ‘If you turn us around, we will run out of gas.’ And the air – traffic controller said, ‘I don’t care. Make a one-eighty and get out of here. I don’t want to see you again.’ And I said, ‘You need to get your supervisor because this has all been pre-briefed.’ Pretty soon the airline guys on the same frequency were saying, ‘Hey, come on. This is the guy delivering SpaceShipOne to the National Air and Space Museum.’”

Even after arrangements had been made with the airport and with the officials from the National Air and Space Museum on the ground, Melvill was denied. But he could always be counted on when the situation did not go exactly as planned. With almost no gas, he was able to land on a runway that wasn’t being used by the airlines. After detaching SpaceShipOne from White Knight and spending about an hour on the ground, Melvill lifted off in White Knight. The mothership had left its baby for good. Figure 10.11 shows SpaceShipOne in the Milestones of Flight gallery after the donation ceremony on October 5, 2005, hanging next to Spirit of St. Louis and Glamorous Glennis.

Although SpaceShipOne’s mission was suborbital spaceflight, it was actually able to completely break away from Earth’s gravitational pull. In 2007, a small piece of SpaceShipOne, aboard the space probe New Horizons, zipped by Jupiter on its way to a rendezvous with Pluto and its moon Charon. It will then continue on further to the edge of the Solar System into the mysterious Kuiper Belt, a region of space responsible for the demotion of Pluto from a planet to a dwarf planet after the discovery of a tenth planet. Launched in 2006, this is the first mission aimed at exploring these celestial objects. Figure 10.10 shows a conceptual drawing of the space probe on its journey.

In June of 2015, New Horizons and the SpaceShipOne fragment will have completed the interplanetary cruise phase on the way to Pluto. Earth will be 3.06 billion miles (4.92 billion kilometers) away when the closest approach occurs. Eleven years earlier, to the month, SpaceShipOne had first entered space, giving real hope to those with dreams of floating free in space.

A character in Clarke’s 2010: Odyssey Two, in summarizing what he expected from an upcoming space trip, simply stated, “Something wonderful.” By the time New Horizons actually reaches Pluto, that phrase will be invoked many times thanks to the accomplishments of commercial space travel that are to come.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![]()

В: Chase Plane Crews

|

Flight No. |

Duchess: Low Altitude |

Extra 300: High Altitude |

Alpha Jet: High Altitude |

Starship: High Altitude |

|

01C |

(a) |

(a) |

(a) |

(a) |

|

02 C |

(a) |

(a) |

(a) |

(b) |

|

03G |

(a) |

(a) |

(a) |

(b) |

|

04GC |

Jon Karkow |

Pete Siebold |

||

|

05G |

Jon Karkow |

Pete Siebold |

||

|

06G |

Brian Binnie |

Jon Karkow |

||

|

07 G |

Chuck Coleman |

Brian Binnie |

||

|

08G |

Mike Melvill Chuck Coleman |

Jon Karkow |

||

|

09G |

Chuck Coleman Matt Stinemetze |

Pete Siebold |

||

|

10G |

Mike Melvill Chuck Coleman |

Marc de van der Shueren Jeff Johnson |

Jon Karkow |

|

|

11P |

Mike Melvill Chuck Coleman |

Marc de van der Shueren Jeff Johnson |

Jon Karkow |

|

|

12G |

Mike Melvill Chuck Coleman |

Jon Karkow |

||

|

13P |

Mike Melvill Chuck Coleman |

Marc de van der Shueren Jeff Johnson |

Jon Karkow Robert Scherer |

|

|

14P |

Pete Siebold Dave Moore |

Marc de van der Shueren Jeff Johnson |

||

|

15P |

Chuck Coleman Cory Bird |

Marc de van der Shueren Jeff Johnson |

Jon Karkow Robert Scherer |

|

|

16P |

Chuck Coleman Cory Bird |

Marc de van der Shueren Jeff Johnson |

Jon Karkow Robert Scherer |

|

|

17P |

Chuck Coleman Cory Bird |

Marc de van der Shueren Jeff Johnson |

Jon Karkow Robert Scherer |

|

(a) Data not reported in SpaceShipOne/ White Knight Flight Log. (b) The Starship, owned by Robert Scherer, was flown during this flight, but the crew was not reported. |