X2: Winning the Ansari X Prize (17P)

On this day, the 47th anniversary of Sputnik, Brian Binnie was selected to pilot SpaceShipOne for the second of the two flights required to win the Ansari X Prize. Melvill, who had been a backbone of the program, had paved the way for Binnie only five days earlier. Melvill would now be there flying White Knight along with Matt Stinemetze as flight engineer.

Gone.

Flight Test Log Excerpt for 17P

Date: 4 October 2004

Flight Number Pilot/Flight Engineer

SpaceShipOne 17P Brian Binnie

White Knight 66L Mike Melvill/Matt Stinemetze

Objective: Second X Prize flight: again ballasted for 3 place and 100 kilometer goal (328,000 ft). (We also really wanted to break the X-15 354 kft [thousand feet] record.)

(source: Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, provided courtesy of Scaled Composites)

V___________________________________________________________

“He dropped me, and I dropped him,” Melvill said. “That was fun.”

White Knight and SpaceShipOne lifted off together at 6:49 a. m. PST on October 4, 2004, in the chill of the desert morning with the Sun rising. In an article Binnie wrote for Air <$_ Space, he echoed the thoughts of Melvill, “The program to develop and test Burt Rutan’s SpaceShipOne (SSI) had many different demands, but I can safely say the one that made the pilots uniformly uncomfortable was the hour – long wait in SSI while the White Knight carrier aircraft dragged it up to release altitude. During this time, there is little to do and the mind is somewhat free to wander.”

As the world watched, the pressure on Binnie was enormous. With the prize of $10 million on the line, Branson waiting down below poised to begin work on SpaceShipTwo, and the fact that it was ten months since the last time he flew SpaceShipOne, which resulted in a crash landing, Binnie had plenty to wrestle with inside his head. “For me personally, a problem or failure or inability to pull this off for whatever reason, the other side of that coin was a bottomless pit. It felt to me like an abyss.”

Tensions ran high on the ground, too. “I knew that if there would be any glitches, people would say that this is not ready for prime time,” Ansari said. “And it’s not ready for commercialization and all these things.”

But when it came time to launch, every trace of doubt or uncertainty disappeared with the first flash of the rocket engine. Binnie’s years of navy flying and skills as test pilot took control. At 7:49 a. m., an hour after takeoff, and 47,100 feet (14,360 meters), Stinemetze pulled the lever to drop SpaceShipOne.

Table 9.1 gives the transcript of the communication between Binnie and Mission Control from the moments before separation to when the feather was locked down after reentry.

“We had no reason to delay,” Binnie said. “So, as soon as I was separated, I armed and fired the rocket motor.”

Ignition occurred immediately, and off Binnie went. SpaceShipOne zoomed past White Knight close enough for Melvill and Stinemetze to hear the hybrid rocket engine, a spaceman’s version of buzzing the tower. Figure 9.10 shows SpaceShipOne beginning to make its turn toward space. After 10—12 seconds, Binnie was thinking, “Okay, I’m still alive. I’m still in the loop. I’m still managing this thing.” But as SpaceShipOne transitioned into supersonic flight, he relaxed. The hardest part was over.

“We wanted to get to the X Prize altitude and a secondary goal of trying to beat the X-15 record,” Binnie said. “So, we wanted lots of altitude. But we also wanted to exit the atmosphere without any rolls or gyrations or large body rates so that we didn’t scare off Branson and the whole SpaceShipTwo efforts. There was that dual-edge sword of precision flying on one side and performance on the other.

“We wanted to get the nose up to 60 to 70 degrees as quickly as we could, initially, a very aggressive turn,” Binnie continued. “Once we got there, we started slowing down the pitch rate on the vehicle so that we went from 60 degrees to about 80 to 82 degrees over the next 50 seconds or so. The bulk of the flight was just milking the nose between those pitch attitudes. And then the last 20 to 25 seconds was the start of a pull again to get to about 87 to 88 degrees nose up.”

г

![]() Fig. 9.10. Brian Binnie faced the toughest flight of his entire life on October 4, 2004. He hadn’t flown SpaceShipOne since the crash landing. Now he was behind the controls of SpaceShipOne while the world’s eyes watched his every move. Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, video capture provided courtesy of Discovery Channel and Vulcan Productions, Inc.

Fig. 9.10. Brian Binnie faced the toughest flight of his entire life on October 4, 2004. He hadn’t flown SpaceShipOne since the crash landing. Now he was behind the controls of SpaceShipOne while the world’s eyes watched his every move. Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, video capture provided courtesy of Discovery Channel and Vulcan Productions, Inc.

s________________________ ;

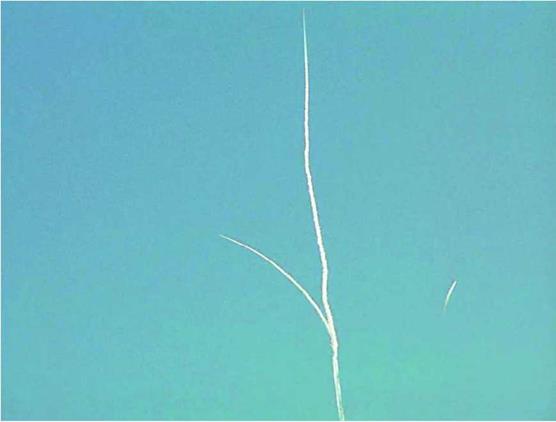

The exhaust from SpaceShipOne s rocket engine streaking upward as the contrail from White Knight veers off to the left can be seen in figure 9.11.

Binnie continued, “The initial pitch attitude to 60 to 65 degrees meant you were going to take advantage of all that rocket motor energy that is available to you and convert that to altitude. And the pull-in endgame meant you were keeping angle of attack on the vehicle and making it less susceptible to rocket-motor asymmetry in the thin upper atmosphere, where you have a delicate balance between controlling those asymmetries with little aerodynamic control power to resist it.”

After 84 seconds, Binnie shut down the rocket engine when SpaceShipOne had reached 213,000 feet (64,920 meters), zipping upward as fast as Mach 3.09 (2,186 miles per hour or 3,518 kilometers per hour). Like a pot of gold at the end of a rainbow, $10 million waited at the other end of the ballistic arc.

“I went scooting right through the X Prize altitude and past the X -15 old record by 13,000 feet [3,960 meters] or so. I got to the point after rocket motor shutdown and the feather coming up, and I hadn’t touched any of the reaction control system yet to control body rates. The vehicle was just absolutely stable. I actually used reaction control to give myself a different view so I could take some pictures.”

C ^

C ^

Fig. 9.11. The contrail of SpaceShipOne streaks spaceward as the contrail of White Knight peels off to the left. Brian Binnie fired the rocket engine for 84 seconds, shutting it down at 213,000 feet (64,920 meters). Dan Linehan

V J

г ^

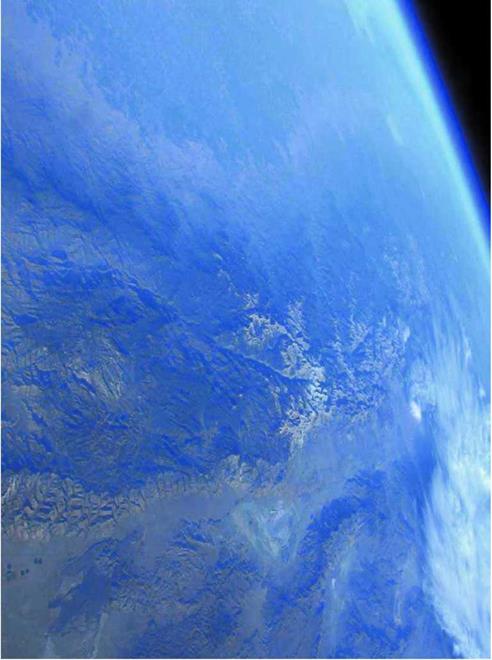

Fig. 9.12. Well past the boundary of space, Brian Binnie had entered the black sky. SpaceShipOne coasted to an apogee of 367,500 feet (112,000 meters), surpassing the X-15 altitude record of 354,200 feet (108,000 meters). Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, photograph by Scaled Composites

Fig. 9.12. Well past the boundary of space, Brian Binnie had entered the black sky. SpaceShipOne coasted to an apogee of 367,500 feet (112,000 meters), surpassing the X-15 altitude record of 354,200 feet (108,000 meters). Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, photograph by Scaled Composites

V J

Binnie reached an apogee of 367,500 feet (112,000 meters), which exceeded the Ansari X Prize requirements by nearly 7.5 miles (12 kilometers), and experienced weightlessness for more than 3.5 minutes. Binnie had a little time to take pictures, and figure 9.12 shows one of his photographs. In addition to taking photos, as figure 9.13 shows, he had the chance to do some zero-g testing on a miniature SpaceShipOne. Binnie did not release M&Ms in space as did Melvill, and it’s still unconfirmed whether Binnie ate his allotment during the captive-carry phase. Doug Shane would not speculate on the origin of several faint crackling sounds heard over the Mission Control radio.

Although weightless at apogee, SpaceShipOne had not truly escaped Earth’s pull. SpaceShipOne started to freefall and began to

accelerate, reaching Mach 3.25, which was the fastest speed it had ever reached on any of the flights. As SpaceShipOne descended into the thick atmosphere, air friction now decelerated it, and at 105,000 feet (32,000 meters), Binnie faced a peak force of 5.4 g’s pushing against his body.

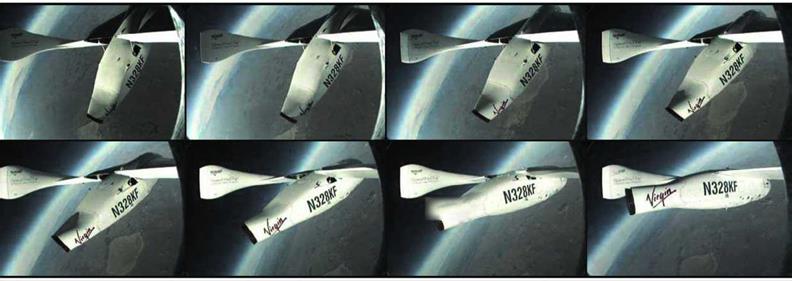

As the g-forces subsided and SpaceShipOne slowed down below the speed of sound, Binnie retracted the feather at an altitude of 51,000 feet (15,540 meters). The video frames, at two-second intervals, in figure 9.14 show the transition of the feather mechanism from the extended position to the retracted position. After reentry into Earth’s atmosphere, the feather had done its job. The pair of pneumatic actuators, which can be seen connecting either side of the fuselage to the trailing edge of the

r~

r~

Fig. 9.13. Brian Binnie’s trajectory was spot-on during the ascent. The hard part was over, now that gravity had taken over control of the trajectory. Binnie had 3.5 minutes of weightlessness to savor. He snapped photos and sailed a SpaceShipOne model back and forth across the cockpit. Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, video capture provided courtesy of Discovery Channel and Vulcan Productions, Inc.

Fig. 9.13. Brian Binnie’s trajectory was spot-on during the ascent. The hard part was over, now that gravity had taken over control of the trajectory. Binnie had 3.5 minutes of weightlessness to savor. He snapped photos and sailed a SpaceShipOne model back and forth across the cockpit. Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, video capture provided courtesy of Discovery Channel and Vulcan Productions, Inc.

V_________________________________________________________

wings, pulled downward. This caused the feather to retract, making SpaceShipOne streamlined once more and readying it for the glide back to Mojave.

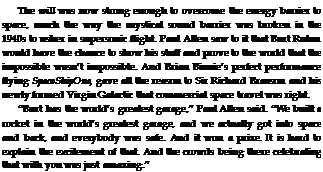

SpaceShipOne, now configured as a glider, drifted homeward. Figure 9.15 shows Sir Richard Branson, Paul Allen, and Burt Rutan spotting SpaceShipOne in the sky above Mojave.

The world watched SpaceShipOne gliding down for 18 minutes.

“I don’t know,” Ansari said, “maybe naively, I just felt that there was no more danger and everything would be fine or if there were any glitches or problems, they would be very much manageable. I wasn’t too worried because I had watched landings of SpaceShipOne a few times before.”

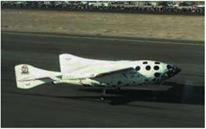

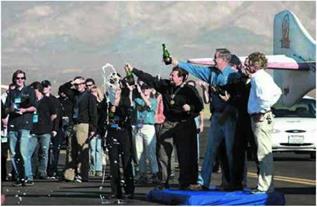

After only 24 minutes from being dropped by White Knight, SpaceShipOne’s wheels hit the runway for a perfect landing, as shown in figure 9.16.

“Oh, it was absolutely wonderful,” said the 434th human to reach space, summing up his spaceflight.

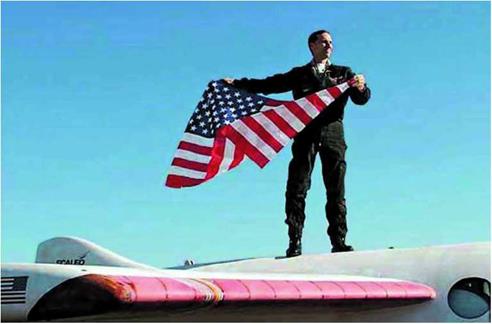

Once the nose skid brought SpaceShipOne to a stop and the door popped open, Binnie was instantly welcomed back by his wife as Rutan, Allen, and Branson congratulated him on the victorious flight. Towed by a pickup truck, SpaceShipOne paraded up and down the flightline in front of the thousands and thousands of cheering supporters as Binnie stood triumphantly atop, as shown in figure 9.17.

“The whole experience was very emotional for me,” Ansari said. “Even though I had nothing to do with the design and the hard work that the engineers and the team had put into building SpaceShipOne, I just felt like part of the team. I was just so proud and happy that they were successful, and that was the greatest joy to see that happen.”

Eight years after it was announced, the Ansari X Prize was finally captured, just like the Orteig Prize, first offered in 1919 and claimed in 1927. The difference was that aviation would not just take a giant leap into the air but would leap past where the air was thin to the beginning of space.

Г Л

Fig. 9.14. As SpaceShipOne fell back to Earth, the feather eased it into the atmosphere. At 51,000 feet (15,540 meters), Binnie retracted the feather, as shown by the sequence given at two-second intervals. Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, video captures provided courtesy of Discovery Channel and Vulcan Productions, Inc.

ґ

![]() Fig. 9.15. Sir Richard Branson, Burt Rutan, and Paul Allen (left to right), search the sky and spot SpaceShipOne as it nears the end of its 24-minute journey up and down from space. X PRIZE Foundation

Fig. 9.15. Sir Richard Branson, Burt Rutan, and Paul Allen (left to right), search the sky and spot SpaceShipOne as it nears the end of its 24-minute journey up and down from space. X PRIZE Foundation

v___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

f

f

Fig. 9.16. Brian Binnie finished his flawless performance by making a perfect landing. After about a year and a half of flight testing, seventeen flights altogether, SpaceShipOne touched down on the runway for the last time. Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, video capture provided courtesy of Discovery Channel and Vulcan Productions, Inc.

V_________________________________________________

г ^

Fig. 9.17. In a matter of days, not weeks, SpaceShipOne made two spaceflights. No other vehicle in the history of space travel had accomplished this feat. Brian Binnie’s performance not only restored his confidence in himself but made it clear to the world that the future of space travel was happening right here, right now. X PRIZE Foundation

Fig. 9.17. In a matter of days, not weeks, SpaceShipOne made two spaceflights. No other vehicle in the history of space travel had accomplished this feat. Brian Binnie’s performance not only restored his confidence in himself but made it clear to the world that the future of space travel was happening right here, right now. X PRIZE Foundation

|

|

___________________ J

r ; >

r ; >

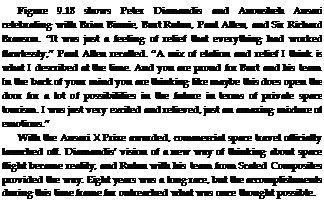

Fig. 9.18. SpaceShipOne had done it. Eight years after its announcement by Peter Diamandis and the X Prize Foundation,

Brian Binnie had captured the Ansari X Prize. Burt Rutan, Paul Allen, and the rest of their team had pulled off the seemingly impossible.

Now was the time to celebrate the historic accomplishment and also to revel in the wonderment as the door to space flung wide open.

X PRIZE Foundation

V__________________ )

Table 9.1 Transcript of SpaceShipOne’s Ansari X Prize-Winning Spaceflight

This transcript was prepared using video filmed during the second Ansari X Prize spaceflight attempt from inside the cockpits of SpaceShipOne and White Knight and from inside Mission Control. The spaceflight was called X2 because it was the second attempt required by the Ansari X Prize and also called 17P because this rocket-powered flight was the seventeenth time SpaceShipOne flew. White Knight lifted off with SpaceShipOne from Mojave’s Runway 30 at 6:49 a. m. PST on October 4, 2004. The entire spaceflight lasted 1.6 hours (wheels up to wheels down for White Knight). The time stamps are hours:minutes:seconds a. m., PST. The transcript runs from just before SpaceShipOne is dropped from White Knight to just past feather retraction and lock after reentry. Acronyms used are:

AFFTC: Air Force Flight Test Center at Edwards Air Force Base

AST: Federal Aviation Administration Office of Commercial Space Transportation

BB: Brian Binnie in SpaceShipOne

BR: Burt Rutan in Mission Control

DS: Doug Shane in Mission Control

MC: Staff in Mission Control

MM: Mike Melvill in White Knight

MS: Marc de van der Schueren in the Alpha Jet chase plane

SS1: SpaceShipOne

|

Time stamp and speaker |

Dialogue |

Notes |

|

7:49:17 MM |

"SCUM status?" |

The Scaled Composites Unit Mobile (SCUM) was a mobile ground control station. |

|

7:49:19 DS |

"SCUM is go for release and ignition, elevons to go." |

BB pushes the control stick forward, preparing for release. |

|

7:49:22 MM |

"Three. Two. One." |

|

|

7:49:25 MM |

"Release." |

|

|

7:49:27 BB |

"Release." |

|

|

7:49:28 BB |

"Armed." |

|

|

7:49:28 BB |

"Fire." |

|

|

7:49:32 BB |

"Good light." |

|

|

7:49:37 DS |

"Coming up ten seconds, Brian." |

Rocket engine burn time at 10 seconds. |

|

7:49:39 BB |

"Copy." |

|

|

7:49:42 DS |

"Rates look good and low." |

|

|

7:49:46 DS |

"Okay, start the nose-down trim." |

The trajectory must be timed in order to end up at zero angle of attack as late as possible. |

|

7:49:49 DS |

"Looking great at twenty seconds." |

Rocket engine burn time at 20 seconds. |

|

7:49:54 DS |

"Doing okay?" |

|

|

7:49:55 BB V |

"Doing alright." |

|

(Source: Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, provided courtesy of Scaled Composites) |

|

7:49:58 DS |

"Copy that. Thirty seconds, a little nose up trim is probably okay now." |

Rocket engine burn time at 30 seconds. |

|

7:50:02 MM |

"You look great." |

|

|

7:50:07 BB |

"Starting to settle out." |

|

|

7:50:09 DS |

"Okay, forty seconds." |

Rocket engine burn time at 40 seconds. |

|

7:50:10 DS |

"The energy’s on the line. The trajectory looks good." |

The actual trajectory is tracking with the predicted trajectory. |

|

7:50:13 BB |

"Copy." |

|

|

7:50:16 DS |

"Touch of nose up trim." |

|

|

7:50:19 DS |

"Fifty seconds." |

Rocket engine burn time at 50 seconds. |

|

7:50:21 DS |

"Two hundred energy." |

This reading stands for a projected altitude of 200,000 feet (60,960 meters) for SS1. It does not stand for SSI’s actual altitude. Both MC and AFFTC use energy altitude predictors to project the maximum altitude SS1 would reach if its rocket engine were to shut off and SS1 were to coast the remainder of the way up. The projected altitude gives an indication at any given time whether or not SS1 will reach the target altitude of 328,000 feet (100,000 meters). |

|

7:50:22 DS |

"A little right roll trim." |

A slight correction is made to the trajectory. |

|

7:50:26 DS |

"Nose pitch up, Brian, nose up trim." |

|

|

7:50:30 BB |

"There is the shaking." |

The liquid to gas transition, which occurs as the N20 begins to run low in the oxidizer tank, causes this to happen. |

|

7:50:31 DS |

"Okay." |

|

|

7:50:33 DS |

"Roll right." |

|

|

7:50:36 DS |

"Three hundred thousand." |

The predicted altitude is 300,000 feet (91,440 meters). |

|

7:50:41 DS |

"Three twenty-eight." |

The predicted altitude is 328,000 feet (100,000 meters). |

|

7:50:44 DS |

"Radar is three twenty-eight." |

The predicted altitude is 328,000 feet (100,000 meters) as measured by AFFTC. |

|

7:50:45 BB |

"Copy that." |

|

|

7:50:48 DS |

"Three fifty suggest shutdown." |

The rocket engine is still firing, and if it is shut down at this point, SS1 will coast to 350,000 feet (106,700 meters). |

|

7:50:53 BB |

"Roger. Shutdown." |

BB lets the rocket engine burn an extra 4-5 seconds. |

|

7:50:58 BB |

"And the rates look good." |

|

|

7:51:00 DS |

"Okay. Copy that." |

|

|

7:51:01 DS |

"You are going to want to track north for the entry." |

A box, approximately 2.5 square miles in size, is set by AST for SS1 to make the reentry. |

|

7:51:03 DS |

"You are just across the orange line on the south." |

The orange line is an AST boundary. |

|

г

|

|

( 7:52:37 BR |

"Ten thousand feet over X-15." |

This comment is made in MC and not heard over the radio. |

|

7:52:48 BB |

"Boy, it’s really quiet up here." |

|

|

7:52:59 DS |

"Okay, flight is through this position coming downhill through three fifty." |

The actual altitude of SS1 is 350,000 feet (106,700 meters). |

|

7:53:03 DS |

"And current position is five southwest." |

|

|

7:53:06 DS |

"Correction, five south of the bull’s-eye." |

The bull’s-eye is the center of the AST box. |

|

7:53:08 DS |

"Looks like the entry point is between main base and north base." |

This is to let the chase planes know that reentry will occur between Mojave Air and Space Port and Edwards Air Force Base. |

|

7:53:17 DS |

"Brian, if you can keep it upright for GPS, that’s good." |

|

|

7:53:19 DS |

"And, again, orient northwest please for the entry." |

|

|

7:53:25 BB |

"Copy that, Doug." |

|

|

7:53:36 DS |

"And Brian, a little blip of right yaw trim would be good." |

|

|

7:53:43 DS |

"That looks great." |

|

|

7:53:45 DS |

"Doing okay?" |

|

|

7:53:48 BB |

"I’m doing great, Doug. Uh, camera is, uh, stowed again." |

|

|

7:53:54 DS |

"Copy that, passing two six zero." |

The actual altitude is 260,000 feet (79,250 meters). |

|

7:54:03 BB |

"And it’s northwest you want for the heading right?" |

|

|

7:54:06 DS |

"Affirmative." |

|

|

7:54:09 DS |

"That’ll point you back at high key." |

High key is a glide mode of the TONU. |

|

7:54:21 DS |

"All systems are green here, Brian." |

|

|

7:54:22 DS |

"Don’t worry about temps in the back end." |

|

|

7:54:24 DS |

"We’re looking good here." |

|

|

7:54:26 MS |

"Alpha’s got a visual." |

The Alpha Jet chase plane spots SS1. |

|

7:54:27 BB |

"Okay, here comes the g’s." |

|

|

7:54:29 DS |

"Copy that." |

|

|

7:54:31 DS |

"One hundred fifty thousand." |

The actual altitude is 150,000 feet (45,720 meters). |

|

7:54:37 BB |

"There’s three." |

BB is referring to the number of reentry g’s. |

|

7:54:41 DS |

"Max Mach is past three two six." |

SS1 reaches a maximum of Mach 3.25. |

|

7:54:45 BB |

"Five g’s." |

|

|

7:54:58 DS |

"Peak g is passed." |

![]()

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

SpaceShipOne’s journey had not ended with the Ansari X Prize, although the mission and the destination had substantially changed. SpaceShipOne was about to embark on two of its longest flights ever, one across the United States and one across the Solar System. Tyson V. Rininger