X1: The First Ansari X Prize Flight (16P)

“Ladies and gentlemen, we are at the start of the personal spaceflight revolution, right here, right now. It begins in Mojave, today. What is happening here in Mojave today is not about technology. It is about a willingness to take risk, to dream, and possibly to fail,” said Peter Diamandis during the morning of September 29, 2004, as XI, the name of the first required flight of SpaceShipOne in the quest for the Ansari X Prize, prepared to launch.

Mojave was abuzz. A little more than three months earlier, Mike Melvill had earned his astronaut wings as he piloted SpaceShipOne on a history-making flight just past the 100- kilometer (62.1 miles or 328,000 feet) line demarking the start of space. Now Rutan’s team set their sights on the most exciting and influential prize of the new millennium.

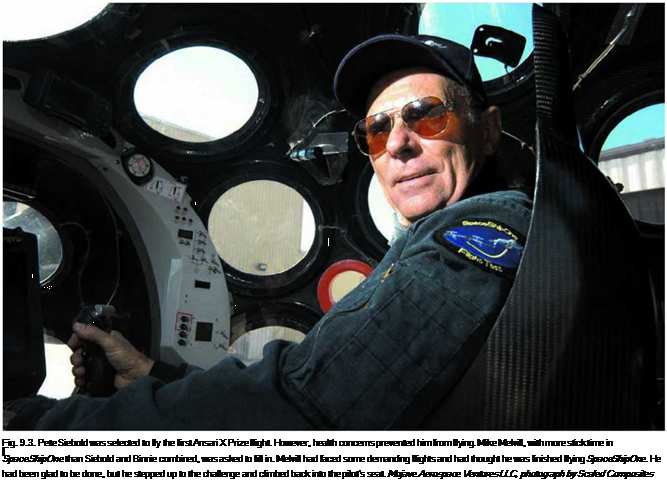

Pete Siebold, who had already flown two glide flights and one powered fight in SpaceShipOne, was selected to pilot the flight. Siebold had been training for three years for this moment, but a health scare forced a very disappointing change.

“There were two other guys that were more than qualified to fly that flight,” Siebold said. “At the time, I didn’t feel as though I was doing the team any justice by putting myself in that situation and flying

the mission when I probably wasn’t in the right frame of mind and not to mention healthy enough.” Siebold made the tough decision, but very fortunately his health issues were eventually determined to be nowhere near as serious as first suspected.

Rutan then turned to the test pilot with the most experience flying SpaceShipOne. Mike Melvill would get his chance to become an astronaut a second time, but to do so, he’d have to get back into training again. Figure 9.3 shows Melvill at the controls in the cockpit of SpaceShipOne preparing for XI.

Like Spirit of St. Louis, SpaceShipOne was stripped of anything absolutely nonessential. The lighter the craft, the greater the margin SpaceShipOne had for clearing the 100 kilometers (62.1 miles or 328,000 feet) because the removal of each and every pound enabled the spacecraft to go an additional 150 feet (46 meters) higher. SpaceShipOne needed all the help it could get. Melvill’s earlier spaceflight had cleared the 100 kilometers by only the slimmest of

margins, less than 500 feet (150 meters). And during this spaceflight, SpaceShipOne was not even carrying the full payload required by the rules of the Ansari X Prize.

Ironically, as the Scaled Composites team scrimped for a pound here and a pound there, removing a total of about 45 pounds (20 kilograms), they would have to add weight to simulate two passengers. “We had to carry 400 pounds [180 kilograms] in the back seat, which was a heck of a lot more load in that thing than we ever had before. And I had to be ballasted,” Melvill said.

Since Melvill weighed only 160 pounds (73 kilograms), he had to be ballasted up to 200 pounds (90 kilograms).These were the rules. But keeping the gross weight as low as possible was still critical. Every pound that didn’t have to be carried was a pound that the force from the rocket engine didn’t have to lift.

Figure 9.4 shows Melvill gesturing “okay” from a removable port as final preparations were made. SpaceShipOne was carried

|

ґ

Fig. 9.4. Mike Melvill gives the thumbs up from the cockpit of SpaceShipOne as last-minute preparations are made. For the Ansari X Prize,

SpaceShipOne had to carry enough weight to simulate three 198-pound (90-kilogram) people. SpaceShipOne just barely made it past 328,000 feet (100,000 meters) without the extra weight, so it was necessary to bump up the performance of the rocket engine. Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, photograph by David M. Moore

into the air at 7:12 a. m. PST by White Knight with Brian Binnie behind the controls.

Separation occurred at 8:10 a. m. PST when flight engineer Matt Stinemetze, who sat in the back seat of White Knight, released SpaceShipOne from an altitude of 46,500 feet (14,170 meters). Clear of White Knight and no longer pushing forward on the control stick, Melvill fired the rocket engine, which had been enhanced to provide greater performance by increasing the amount of propellant and burn time.

“You could sure hear it,” Melvill said. “It was very loud—it was extremely loud.

“But it is a fabulous ride going up. I think that people who go on the next one—the passengers—will get the most exciting thing they ever did. A lot of noise. They are going really fast. The acceleration is dramatic. You are accelerating at a huge rate. You just watch the speed going up.”

The cockpit shook as Melvill pulled the nose up, making a very sharp turn toward the sky above. “The straighter you flew it, the

|

|

f ^

Fig. 9.5. A video-capture image shot from a chase plane shows SpaceShipOne spiraling up during its boost. Melvill struggled to control the rolls but still allowed SpaceShipOne’s rocket engine to fire so he would be sure to pass the 328,000-foot (100,000-meter) mark. SpaceShipOne rolled twenty-nine times. Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, video capture provided courtesy of Discovery Channel and Vulcan Productions, Inc.

V__________________ )

higher it would go in the same amount of time,” he said. “We didn’t need to burn the motor for its full length that it was capable of burning because it went up there quite easily.”

During his previous flight, though, he had battled wind shear, rocket asymmetries, and pitch control failure. These had prevented him from flying a very straight trajectory. Melvill was more than determined to nail the trajectory on this flight.

As SpaceShipOne blasted through the upper atmosphere, Melvill had closed up the two donuts on theTONU display, which meant he was doing a great job flying the planned trajectory, and he monitored the energy altitude predictor, an instrument that predicted how high SpaceShipOne would go once the rocket engine was shut down.

“You may be at 160,000 feet [48,770 meters],” Melvill said, “and it will say, if you turn it off right now, you’ll go all the way to 328,000 feet [100,000 kilometers]. So, you watch that instrument. That’s the primary instrument to know when to turn it off. Initially, we did it with a timer, and we just said you’re going to run 55 seconds. And at the end of 55 seconds, we’d shut it off.”

But only 60 seconds after lighting the rocket engine, traveling at Mach 2.7, SpaceShipOne was in trouble. The crowd hushed as the contrail from SpaceShipOne switched from a nice, smooth line to a wild corkscrew in the sky. Things happened fast. But from the angle of the shot displayed on the jumbo screen, it was hard to tell what was actually happening. Figure 9.5 shows SpaceShipOne rolling out of control, viewed from the cockpit of a chase plane.

“When he started doing the rolls, I thought he was dead,” recalled Erik Lindbergh. “I thought that was it—the craft was going to break up and he was done.”

Thousands of people were gripped in silence.

“I didn’t think he was doing rolls. I thought he was tumbling at that point,” Lindbergh recalled.

SpaceShipOne rolled right uncontrollably at an initial rate of 190 degrees per second, spiraling up toward space.

“I had one of the walkie-talkies, and I could hear Melvill talking to ground control,” Ansari said. “He said that everything is fine. It didn’t look fine. But because he was convinced that everything was fine, I felt comfortable.”

The rocket engine kept burning while SpaceShipOne still spun its way up, reaching a maximum speed of Mach 2.92 (2,110 miles per hour or 3,400 kilometers per hour). Melvill still kept his eye on the energy altitude predictor. As he explained, “Unless you see 328,000 feet [100,000 meters] in that window, you are not going to win the X Prize. So, you don’t want to turn it off until you read at least that much or more. And so that was why I didn’t turn it off when we were doing all those rolls, because it didn’t say 328,000 feet [100,000 meters] yet. I went to turn it off thinking, wow, something was wrong here. And when I looked at the energy height predictor, it was not predicting that we would go high enough. So, I just left the motor running and just ignored the rolling.”

At a total burn time of 77 seconds, Melvill finally shut off the rocket engine. His altitude was 180,000 feet (54,860 meters) at that point and only about halfway through its ascent. But as Melvill got higher and higher, the air became too thin for him to counteract the rolls with either the subsonic or supersonic flight controls. SpaceShipOne left the atmosphere still rolling at 140 degrees per second.

Melvill was able to keep from being disoriented by focusing on the Tier One navigation unit and not glancing out the windows. He activated the feather and then focused on nulling-out the rolls with the reaction control system. “I just pushed it on, turned on both systems, and just left it on until it stopped it,” Melvill said.

By the time SpaceShipOne stopped rolling, it had completed twenty – nine rolls. The vehicle now continued to coast to an apogee of 337,700 feet (102,900 meters), but now Melvill could enjoy the 3.5 minutes of weightlessness and the view while still having time to take a few photos out the window.

On reentry, SpaceShipOne hit a top speed of Mach 3.0. Still in the feathered configuration, it decelerated from supersonic to subsonic,

|

|

Ґ

Fig. 9.6. By using the reaction control system (RCS), Mike Melvill stopped the rolls. He reached an apogee of 337,700 feet (102,900 meters), which gave him about 10,000 feet (3,000 meters) to spare.

Now, coming down was the easy part. Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, video capture provided courtesy of Discovery Channel and Vulcan Productions, Inc.

V__________________ )

л

л

Fig. 9.7. SpaceShipOne’s second spaceflight was nearly over as it approached Mojave’s runway. But before Melvill had gotten close to the airport, he did some early celebrating by rolling SpaceShipOne once more to make it an even thirty. Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, video capture provided courtesy of Discovery Channel and Vulcan Productions, Inc.

V___________________ J

|

|

|

|

|

г ; л

Fig. 9.9. On October 4, 1957, Sputnik became the first man-made object to orbit Earth. The Soviet Union had launched the beach ballsized satellite, which circled the planet for three months. Sputnik put the space race between the United States and Soviet Union into overdrive. Decades later, on this day, SpaceShipOne was ready to finish a race of its own. NASA

V__________________ )

while it reached a peak g-force of 5.1 g’s at 105,000 feet (32,000 meters).

At 61,000 feet (18,590 meters), Melvill retracted the feather to begin his glide back to Mojave. As SpaceShipOne descended, the chase planes caught up and tucked in behind. Figure 9.6 shows the view of SpaceShipOne from the Alpha Jet.

During the 18-minute glide to Mojave, SpaceShipOne suddenly rolled completely around, surprising the chase planes. But this roll wasn’t uncommanded. Melvill performed a victory roll, rounding out his total rolls for the flight at thirty.

Figure 9.7 shows SpaceShipOne coming in for a landing as the crowds lining the runway cheered.

“It was fabulous—it really was—knowing that we at least were halfway there. We went plenty high. And coming back and all the excitement, everybody was just thrilled to death,” Melvill said.

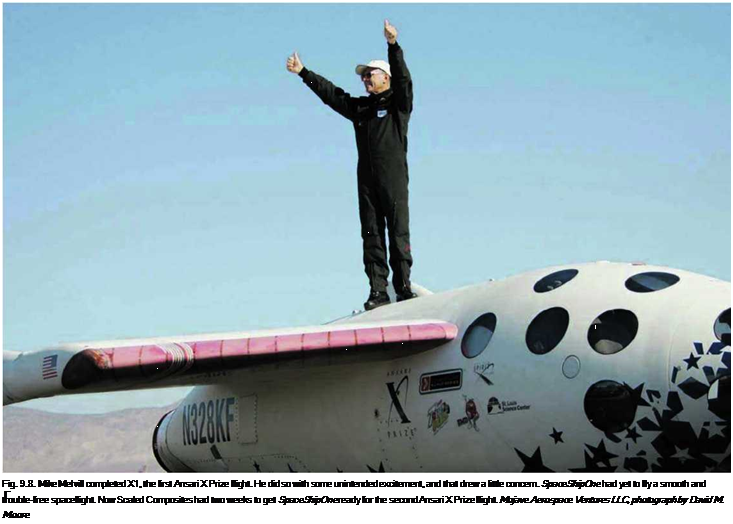

Melvill’s flight exceeded the altitude requirement by nearly 10,000 feet (3,050 meters) and satisfied the other rules set by the Ansari X Prize. To fulfill the remaining conditions, SpaceShipOne had to repeat the spaceflight within two weeks. Standing on SpaceShipOne, Melvill celebrated successfully completing the XI, as shown in figure 9.8.

“We knew what we had to do. My task was to not damage the airplane. I wasn’t going to go for any altitude records but just plenty of margin and burn the engine as little as possible and land the airplane as smooth as possible so we didn’t have to fix anything. We didn’t even change the tires. We refueled it, and it was ready to go. We could have gone the next day,” Melvill said.