First Commercial Astronaut (15P)

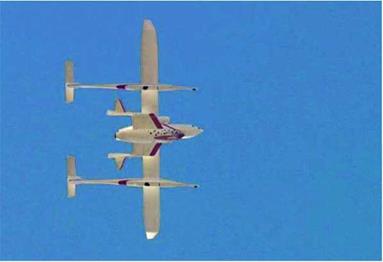

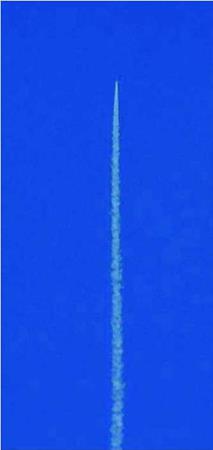

At 6:47 a. m. PST on June 21, 2004, White Knight lifted off from Mojave’s Runway 30, as shown in figure 8.10, to the cheers of twelve thousand spectators. Several days earlier, Mojave Airport officially became Mojave Air and Space Port after receiving its launch site operator license. It would have been another typical windy desert early morning with the Sun still not fully awake, except for a gangly looking airplane toting a stout little rocket plane on the first part of its journey to the hopeful reaches of space. Figure 8.11 shows the mated pair spiraling up to the launch altitude.

At an altitude of 47,000 feet (14,330 meters), White Knight could no longer guide SpaceShipOne any further and cut the rocket craft free to continue the quest on its own.

“You release the back pressure, and then the airplane starts to climb,” Mike Melvill said. “And at that point you must have the motor running. You unguard the switch that turns the elec – trons on to the ignition system, and you unguard the switch that fires it.

“A rocket motor doesn’t start off like a jet engine. It starts off as hard as it is ever going

Flight Test Log Excerpt for 15P

Date: 21 June 2004

Flight Number Pilot/Flight Engineer

SpaceShipOne 15P Mike Melvill

White Knight 60L Brian Binnie/Matt Stinemetze

Objective: First commercial astronaut flight by exceeding 100 kilometers (328,000 ft).

to be right there. The first time it lights, it is going as strong as it will ever be. In fact, it gets weaker as you go along. The initial kick on your back is very strong—more than 3 g’s. Your eyeballs go in at 3 g’s. And then you make about a 4-g turn. And you do that by just pulling back on the stick. In only 9 or 10 seconds, you are supersonic. You are supersonic about two-thirds of the way through that turn. And then you can’t use the stick anymore. You have to use the trim. So, that transition is something you have to learn in the simulator.”

But before completion of the pull-up, severe wind shear rolled SpaceShipOne to the left. As Melvill tried to regain wings level, SpaceShipOne rolled 95 degrees to the right and then 90 degrees to the left. He soon got control and had SpaceShipOne flying vertical, as in figure 8.12. But he ended up far off course.

A minute into the burn, as the oxidizer ran low in the tank, it began to transition from a liquid to a gas. The roar of the rocket engine made a drastic change. “As it starts sucking gas, it chugs,” Melvill explained. “And it goes boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, like that as it is going up. It really rattles your head. It doesn’t do that for too long. But it is disconcerting the first time it happens. I didn’t know what the heck that was all about.”

But the rocket engine wasn’t finished with its mischief. “The rubber that is on the inside of that thing has got ports in it, pieshaped ports that run the whole length of the rubber fuel. So, as you are burning all the surfaces of the inside of each of these pie-shaped ports, they are coming together. You end up with a plus – sign—shaped piece of rubber that is very thin that runs the whole length of the machine. It will break off eventually and go out the back. That must have broken off and got sideways in the nozzle or something because it made a tremendous bang. It really rattled the airplane. I thought the whole tail had fallen off the airplane.”

To improve the airflow around the rocket engine for this flight, a fairing was added, which extended from the back of the fuselage over the sides of the nozzle. But heat from the rocket engine caused it to buckle. It was necessary to modify the design slightly for the next flight. It was unlikely the source of the sound Melvill heard.

Melvill seriously wondered if he’d be able to make it back, but Mission Control could see that the tail booms were just fine from the live video feed of the onboard camera. Unfortunately, Melvill didn’t have the capability to view this imagery. A failure of the primary pitch trim control, which Melvill needed while moving at supersonic speed, also occurred while the rocket engine blasted away. This only

![]() r~

r~

Fig. 8.10. As White Knight fired up its engines and began taxiing to the runway, it rounded the corner, around the control tower, to find a crowd of twelve thousand well-wishers lined up along the flightline. At 6:47 a. m. on June 21,2004, SpaceShipOne began its first journey into space. Tyson V. Rininger

r ^

r ^

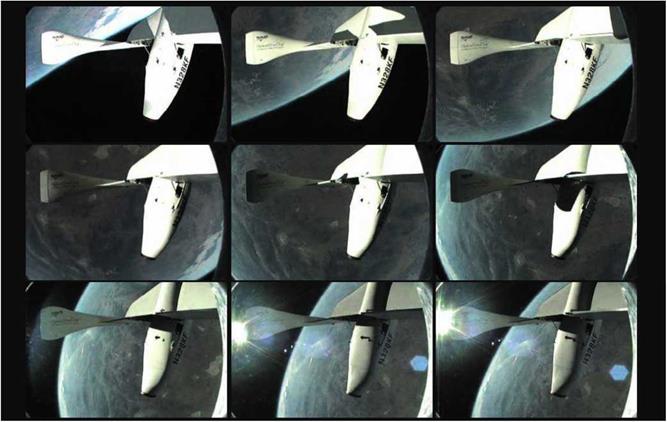

Fig. 8.12. Mike Melvill ignited the rocket engine, "turned the corner," and blasted nearly straight up. The rocket engine burned for 76 seconds and shut down at 180,000 feet (54,860 meters). After reaching a maximum speed of Mach 2.9, SpaceShipOne coasted the rest of the way up to space. Tyson V. Rininger

V_______ )

|

Fig. 8.13. SpaceShipOne reached an apogee of 328,491 feet (100,124 meters), barely above the Ansari X Prize goal. During Mike Melvill’s 3.5 |

minutes of weightlessness, he released two handfuls of M&Ms into the cockpit to float around in zero gravity. Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, video capture provided courtesy of Discovery Channel and Vulcan Productions, Inc.

V__________________ )

deepened his worry. However, he was able to get pitch trim control back by switching to the backup.

Melvill obviously had his hands full, and he wasn’t finished battling the rocket engine. He said, “The thrust is supposed to be right down the centerline. The nozzle is an ablative nozzle. It would burn away, and if it burns away a little bit on one side compared to the other side, you can end up with a yaw going on or a pitch. It burned like about a half a degree from being straight.

“Full rudder would only just deal with a half a degree from asymmetry in the thrust. I put the rudder on the floor, but it still went sideways across the ground. It is just amazing how quickly you go from one place to another if that happens.”

By this point, the good-luck horseshoe pin that Sally Melvill pinned to her husband’s flight suit just before the flight must have weighed five pounds.

“Poor trajectory control drew the airplane way far downrange. It spent an awful lot of energy going downrange rather than straight up where you want it to go,” Doug Shane said.

|

Г

seconds. The shadow of the feather on SpaceShipOne quickly moved position as SpaceShipOne’s orientation to the Sun rapidly changed. Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, screen captures provided courtesy of Discovery Channel and Vulcan Productions, Inc.

Boosting SpaceShipOne to Mach 2.9 (2,150 mile per hour or 3,460 kilometers per hour), the rocket engine cut off at 180,000 feet (54,860 meters) after firing for 76 seconds. SpaceShipOne coasted toward space, but concern rapidly grew whether or not it would reach the Ansari X Prize goal of 328,000 feet (100,000 meters).

Paul Allen could only watch and wait as the Mission Control staff tracked SpaceShipOne’s progress. “You’ve got a human being in a very small projectile that is going straight up at Mach 3,”Allen said, “and me pacing around behind the scenes going, ‘I just want Mike to get back on the ground safely.’ And you got an altimeter that just zips around as SpaceShipOne accelerates upward during the engine burn. And then it starts coasting. The altimeter is just wrapping itself around itself as fast

as it can, and then it starts slowing. You are wondering if SpaceShipOne is going to get high enough, and then it did but barely.”

Before reaching apogee, Melvill raised the feather in preparation for reentry. Gravity was calling SpaceShipOne back, and the spacecraft crept up slower and slower until it finally stopped. Measurements of the altitude were being taken from several different sources, and for a moment, there was nothing but uncertainty. SpaceShipOne did beat the mark by just a fraction, making it to 328,491 feet (100,124 meters), but substantially short of its targeted 360,000 feet (109,700 meters).

Despite the problems Melvill faced in the cockpit, he had a few moments to enjoy the 3.5 minutes of weightlessness. While in zero-g, he wanted to give a good demonstration of the weightless

|

|

![]()

experience. From a zipped pocket on the left arm of his flight suit, Melvill grabbed two handfuls of M&Ms, which he had bought on the way to the airport earlier that morning, and cast the multicolored candies out into the cockpit. Figure 8.13 shows Melvill in the cockpit with M&Ms floating about.

“The sky was jet black above, and it gets very light blue along the horizon. And the Earth is so beautiful, the colors of the Earth, the colors of the high desert, and along the coastline. And all that fog or low stratus that’s over L. A. looked exactly like snow. The glinting and the gleaming of the Sun on that low cloud looked to me exactly like snow,” recounted Melvill at a press conference after the spaceflight.

“And it was really an awesome sight. I mean, it was like nothing I’ve ever seen before. And it blew me away. It really did.”

Figure 8.14 shows video frames, at three-second intervals, of SpaceShipOne, with its feather extended, as it races through space over

Earth. In just a matter of seconds, it moves from one side of Earth to the other. Notice how the shadows change position as the orientation of SpaceShipOne rapidly changes with respect to the Sun. By the last frame, the Sun is behind the portside tail boom.

With the pitch trim control anomaly resolved, all Melvill had to do was let SpaceShipOne’s feather handle the “carefree” return into the atmosphere. SpaceShipOne hit 5.0 g’s while reaching Mach 2.9 during reentry.

“We started out over Boron and wound up directly over the top of the Palmdale VOR [VHF omnidirectional radio beacon]. That is a long way south, right out of the restricted area,” Melvill said. In fact, SpaceShipOne reentered over Palmdale Airport at 65,000 feet (19,810 meters), some 30 miles (48 kilometers) south of Mojave Air and Space Port.

“It was perfectly safe to be flying as an airplane or glider out there,” Doug Shane said.

г ; ^

г ; ^

Fig. 8.17. In a surprise presentation, Patti Grace Smith, the FAA’s associate administrator for Commercial Space Transportation, awarded Mike Melvill the first-ever commercial astronaut wings. In flying SpaceShipOne above 328,000 feet (100,000 meters), Melvill satisfied the primary Tier One goal of getting to space. Now it was time to set the sights on the prize. Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, photograph by David M. Moore

V_____________________________________ )

SpaceShipOne had better than a 60-mile (97-kilometer) glide range. It defeathered at 57,000 feet (17,370 meters) and started to glide back to Mojave.

“I got back to Mojave at 40,000 to 50,000 feet [12,190 to 15,240 meters]. I think we could make it from L. A., LAX probably, if we ended up really off course,” Melvill said.

Doug Shane would eventually get a call from the FAA for a meeting. Palmdale was the location of the air traffic control center responsible for all of Southern California. When Shane met with the FAA, an official enthusiastically said Scaled Composites could have all of LA Center’s airspace, no questions asked. All it would cost is one ride.

Figure 8.15 shows SpaceShipOne coming in for a perfect landing after a tumultuous spaceflight. As the spacecraft came to rest, completing only its fourth powered flight, Melvill, who had worked for Burt Rutan since 1978 and been Rutan’s first employee, became the first commercial pilot of a vehicle to and from space. The Scaled Composites team became the first nongovernment space program to

successfully send a human to space. And figure 8.16 shows Burt Rutan and Paul Allen congratulating Melvill on accomplishing a true milestone of flight. Also waiting to congratulate Melvill was Apollo astronaut Buzz Aldrin, who welcomed him to the club. Melvill became only the 433rd person in space since Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin was the first to reach space in 1961. This works out to an average of ten new people to reach space per year since the very start of human spaceflight.

During a presentation shortly after the spaceflight, the FAA had a surprise for Melvill. “I am very pleased and honored to present, for the very first time, these FAA commercial astronaut wings to Mike Melvill in recognition of this tremendous achievement,” said Patricia “Patti” Grace Smith, associate administrator for the Office of Commercial Space Transportation.

Figure 8.17 shows Melvill with his astronaut wings standing next to Paul Allen and Patti Grace Smith. “I wasn’t expecting anything like that,” said Melvill. “It was really a thrill.”

The FAA now issues astronaut wings to any member of a crew, including passengers, on a spacecraft that exceeds an altitude of 50 miles (80.5 kilometers) during a spaceflight. The 50 miles (80.5 kilometers) was an arbitrary boundary traditionally used by the U. S. military. Internationally, the bar is higher, and the accepted boundary of space, which was used for the Ansari X Prize, is set by the scientifically based Karman Line of 100 kilometers (62.1 miles).

The primary goal of the Tier One space program set by Burt Rutan and Paul Allen had been achieved once SpaceShipOne returned safely to Mojave after reaching space. To that end, SpaceShipOne was optimized for altitude, not payload. Any unnecessary weight would have adversely impacted performance. So, even though SpaceShipOne made it past the Ansari X Prize altitude goal, the passenger requirement wasn’t met.

Scaled Composites had much to think about now that the focus of Tier One was ready to change. Their first spaceflight had not gone entirely as planned, but the Ansari X Prize was now legitimately within reach. Yes, SpaceShipOne had made it to the altitude required by the Ansari X Prize—with only a few hundred feet to spare. Serious problems were encountered, however, and SpaceShipOne wasn’t even hauling the extra weight of a payload. It was necessary to review the spaceflight data and evaluate and repair the damage to SpaceShipOne. Corrective action was required to ensure these mishaps would not repeat and that the performance was improved to meet the demands of the Ansari X Prize.

The Ansari X Prize was to expire in half a year. Within that time, Scaled Composites had to fly two qualifying flights. Six months sounds like a lot of time, but margins of error for spaceflight are razor thin. For the challenges they faced—risking a test pilot’s life and possibly derailing the drive for private spaceflight for many years if something catastrophic occurred—six months were more like six weeks. The need for an additional powered flight before making an attempt at the Ansari X Prize had to be considered.

|