Gliding to Mojave

With the wings returned to the normal flight configuration, SpaceShipOne became a glider. The hard part was certainly over, and the pilot had time to take a breath and take in the view again. But his work was not completely over. Figure 3.17 shows SpaceShipOne gliding over the high desert of Mojave.

If SpaceShipOne was off course during the boost phase, it could be far away from where it needed to land. However, the spacecraft had a glide ratio of seven to one. So, SpaceShipOne had glide range of about 60 miles (97 kilometers) after it defeathered. “It’s got an awful lot of capability to deal with poor trajectory,” Doug Shane said.

The pilot also had to resolve a technical glitch with the global positioning system (GPS) receiver. It would drop out or lose its way during spaceflights. “The GPS receiver was never previously tested in that high and in that fast of a flight regime,” Pete Siebold said. “And so it had software difficulties of its own. The GPS receiver was something you buy from a company off the shelf. It just didn’t perform the way it was supposed to.”

In one of the spaceflights, the GPS receiver reset by itself, but for the other two, the pilot had to reset it.

“So, we had to do a power cycle. The avionics go away while it is booting back up, and then it does a realignment of the inertial navigation system once it powers up again. But we could live with that fault. We had workarounds,” Siebold said.

The spaceship glided down for 10—15 minutes and was much lighter now that the oxidizer and fuel were burned off. SpaceShipOne was not able to land safely with a full load of oxygen and fuel. The extra weight changed the balance, and it was just too heavy for the landing gear to take. So, for an abort, it would have to dump all the nitrous oxide, but it still had to manage with the remaining mass of rubber.

Although SpaceShipOne did a good job gliding down and getting close to the airport, it did not have all the controls or responsiveness of a typical glider, so its maneuvering when it came to landing was limited. Early in the program, a few landing attempts were almost too short or too long for the runway.

Pete Siebold and Brian Binnie modified the landing technique, allowing SpaceShipOne to easily compensate for coming in too high or too low. “We would fly at 8,500 feet [2,590 meters] above sea level above our touchdown point,” Siebold said. “And we had a 360-degree turn to make back to that point again, and then we would be lined up for the final touchdown on the runway. The original technique allowed you to vary the radius of that turn. If you were too low, you could decrease the radius, and your circumference was your flight path. And if you were too low, you could make up for being low on energy by flying that tight radius. Or you could widen it out.

“We also had one last-ditch effort to make any adjustments, and that was to put the landing gear down. When the landing gear was up,

![]()

Ґ

Ґ

Fig. 3.18. Landing proved to be a bigger challenge than anyone had anticipated. There was only one shot at it. SpaceShipOne had to come in at the right altitude and speed or it risked overshooting or undershooting the runway. Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, video capture provided courtesy of Discovery Channel and Vulcan Productions, Inc.

V__________________________________________________

с л

Fig. 3.19. Once SpaceShipOne touched down, steering was very limited. The nose skid and the rear landing gear’s brakes brought the craft to a quick stop, but since it was unpowered, it needed some help to get off the runway. This photograph shows Sir Richard Branson, Paul Allen, and Burt Rutan (left to right) sitting on the tailgate with SpaceShipOne under tow. Dan Linehan

Fig. 3.19. Once SpaceShipOne touched down, steering was very limited. The nose skid and the rear landing gear’s brakes brought the craft to a quick stop, but since it was unpowered, it needed some help to get off the runway. This photograph shows Sir Richard Branson, Paul Allen, and Burt Rutan (left to right) sitting on the tailgate with SpaceShipOne under tow. Dan Linehan

V J

it was a seven-to-one glide ratio. With the landing gear down, it was a four-to-one glide ratio. The problem was that once you put it down, you couldn’t put it back up. So, you had to be sure that you had sufficient elevation to make the runway.”

SpaceShipOne would spiral in for a landing while reaching key altitude points that were provided by the TONU. An energy predictor similar to what was used during boost showed the pilot where SpaceShipOne would be at the key altitudes based on the current turn and descent rates. The pilot would then adjust his speed and turn so that SpaceShipOne would end up at the place it needed to be.

“After we developed that and utilized it, we landed to within 500 feet [150 meters] of a given touchdown point on every subsequent flight. That was real rewarding,” Siebold said.

SpaceShipOne approached the runway at an airspeed of 140 knots indicated airspeed. But in order to put its gear down, it had to perform a special maneuver. “There were other peculiarities with the gear system,” Siebold explained. “You couldn’t put it out at your normal approach speed. So, the speed at which you flew the pattern was too fast to put the gear out and too fast to land. So, what you had to do was in your turn from base to final, you actually had to pull the nose up, slow the airplane down, put the gear out, dump the nose, with gear extension at 125 knots, and then speed back up to 140 knots.” Figure 3.18 shows SpaceShipOne gliding down to the runway at Mojave Airport.

The pilot had one last challenge to face. As it turned out, it was one that Charles Lindbergh faced seventy-seven years previously in

Ґ

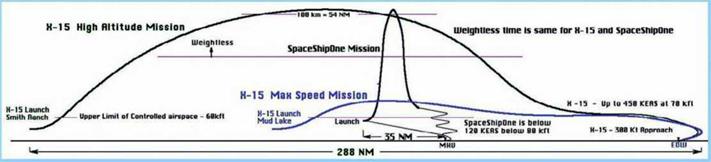

Fig. 3.21. The North American X-15 was the only other manned, winged suborbital vehicle. SpaceShipOne shared some similarities with it, but trajectory was not one of them. The high-altitude and high-speed mission trajectories of the X-15 are shown in comparison to the SpaceShipOne trajectory. Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, provided courtesy of Scaled Composites

г

Fig. 3.20. The X-15 had enough fuel to power its rocket engine for about 2 minutes, so it required a B-52 to lift it to launch altitude. The X-15 flew from 1959 to 1968, posting a top speed of Mach 6.70, or 4,520 miles per hour (7,270 kilometers per hour), and a maximum altitude of 354,200 feet

(108,000 meters) on separate flights. NASA-Dryden Flight Research Center

v_____________________________________________

Table 3.2 SpaceShipOne’s and X-15 Suborbital Mission Comparison

Program goals

Number of vehicles in program Crew capacity

Number of rocket-powered flights

Combined time of rocket-powered flights (hours:minutes:seconds)

Number of flights above 100 kilometers (62.1 miles/328,000 feet)

1 st stage

Separation altitude Engine type Oxidizer and fuel Maximum engine burn time Trajectory for boost and reentry Maximum airspeed Maximum altitude Weightless time Reentry method Reentry max q Approach airspeed Touchdown airspeed Landing surface

Number of vehicles lost during flight testing Number of fatalities during flight testing

X-15

High speed and altitude 3 1

199*

30:13:49*

2

NASA B-52 carrier aircraft

45.0 feet (13,720 meters)

Liquid

Liquid oxygen and anhydrous ammonia 141 seconds (high-speed mission)

Approximately 40 degrees (high-altitude mission) Mach 6.70

354,200 feet (108,000 meters)

3.5 minutes

Pilot controlled pull-up

1.0 psf (550 KEAS)

270 KEAS

180 KEAS Lake bed 1 1

|

the Spirit of St. Louis, which had no front windshield. “The visibility out of SpaceShipOne is pretty restricted, and you got these really small windows, and there is no window in front,” Melvill said. “So, when you are lined up with the runway, you can’t see the runway. With a normal airplane, you can look out the front and see the runway.

“This one, the windows were on the sides, and as long as you were turning toward the runway, you could see it through the side window. But as soon as you lined up with the centerline, you couldn’t see it anymore. The whole airport disappeared. So, that was a little bit

disconcerting I think for all of us. That’s why we had a chase plane sitting right on the wing calling out how high we were above the ground and basically keeping us straight as well.”

At 100 to 110 knots equivalent airspeed, the main landing gear at the rear hit first, and then the nose skid followed. There was no real way to steer once it touched down. The wooden tip of the nose skid brought it to a smooth, but slightly smoky, stop in front of an ecstatic crowd. Figure 3.19 shows SpaceShipOne being towed from the runway accompanied by Paul Allen, Burt Rutan, and Sir Richard Branson.