The Cash Prize

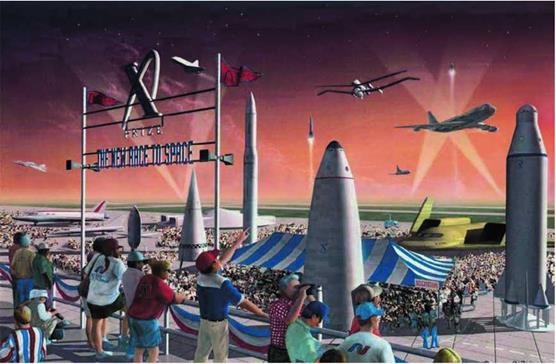

This was all a lot of careful planning, but $ 10 million of prize money does not just materialize out of thin air. This figure does not even include all the expenses needed to run the competition. All totaled, it was a lot of spacebucks. The early conceptual drawing in figure 2.11 gives an indication of the broad, forward thinking of the ambitious X Prize.

In 1995, Diamandis established the X Prize Foundation in Rockville, Maryland, with the help of Maryniak, Lichtenberg, and Colette M. Bevis. That same year Diamandis met Doug King, the president of the St. Louis Science Center, who offered to help raise $2.5 million if the X Prize Foundation would relocate there. St. Louis embraced Diamandis, and with its aviation heritage, the decision to move was an easy one.

During a fundraiser in St. Louis, a local businessman named Alfred Kerth reminded Diamandis that Charles Lindbergh created the Spirit of St. Louis Organization. This organization was a group of ten business leaders who contributed a total of $25,000 to purchase the aircraft used by Lindbergh to cross the Atlantic Ocean. “And Spirit of St. Louis—the airplane—was named after that organization,” Diamandis said. “So Kerth said, ‘Let’s get one hundred people to contribute $25,000 or more from the St. Louis region and call them the New Spirit of St. Louis Organization. It will be the funding mechanism to kick this whole thing off.’ ”

On May 18, 1996, three days before the anniversary of Lindbergh’s historic flight, under the St. Louis Arch, the X Prize was announced. Guests of the ceremony included twenty astronauts; Dan Golden, the administrator of NASA at the time; the Lindbergh family; and Burt Rutan, who on that day made his interest clear. The race was on, and teams had until January 1, 2005, to claim the X Prize.

By 2001, the X Prize was still not fully funded. Bob Weiss, movie producer and vice-chairman of the X Prize Foundation, proposed the idea of a hole-in-one insurance policy to Diamandisrize. With a hole-in-one insurance policy, an insurance company essentially bets against an event happening. This is not uncommon in golf tournaments, where a player can win a car or a great deal of money if he or she makes a hole-in-one on a specific hole on the golf course. If no player makes a hole-in-one, then the insurance company keeps the insurance premiums paid by the tournament organizers and pays nothing out. However, if a player does make a hole-in-one, then the insurance company pays the check.

f ■ ^

Fig. 2.11. The vision of Peter Diamandis and the X Prize Foundation was to rekindle the public’s interest in space and foster the development of private spacecraft that would open the door to the stars for more than just the very limited number of astronauts from government-sponsored programs. X PRIZE Foundation

Fig. 2.11. The vision of Peter Diamandis and the X Prize Foundation was to rekindle the public’s interest in space and foster the development of private spacecraft that would open the door to the stars for more than just the very limited number of astronauts from government-sponsored programs. X PRIZE Foundation

___________________ J

The X Prize Foundation moved ahead with the insurance idea, but premiums were not inexpensive. “I would have to pay out $50,000 every other month sometimes and a large balloon payment at the end,” Diamandis said. “And there were times that I would literally have a week in which to raise $50,000 or I would lose all the premiums I had paid earlier.”

After being in existence for six years, the X Prize was much more fragile than most people knew. It was very difficult to raise money to support the day-to-day operations, let alone funding the $10 million prize money.

During the height of Erik Lindbergh’s involvement, he had become the vice president of the X Prize Foundation. In 2002, he retraced his grandfather’s famous flight on the 75th anniversary of the historic crossing of the Atlantic Ocean by the Spirit of St. Louis. Flying a modern Lancair Columbia 300, named the New Spirit of St. Louis, Eric Lindbergh flew the same flight path but did so in a little more comfort and safety. He could actually see out the front windshield and did not require the use of a periscope. He averaged 184 miles per hour (296 kilometers per hour), and the flight lasted 19.5 hours compared to 108 miles per hour (174 kilometers per hour) and 33.5 hours for his grandfather’s transatlantic flight.

“When I decided to fly across the Atlantic in the Columbia, I did it really to support X Prize,” Erik Lindbergh said. “That was the main thrust of it. That was one of many efforts by individual directors that saved X Prize at a specific period in its history.”

Almost one million dollars was raised, with a majority going to the X Prize. But that wasn’t enough to keep it from ditching before reaching the final destination.

Anousheh Ansari

Anousheh Ansari’s fascination with space and the stars began when she was a little girl living in her native country of Iran. At sixteen, she and her family immigrated to the United States. Ansari, shown in figure 2.12, did not speak English, but education was extremely important to her family. She would pick up the language, a bachelor’s in electronics and computer engineering, and a master’s in electrical engineering on the way to co-founding Telecom Technologies, a multi – million-dollar telecommunications company.

In all this time, her desire for spaceflight never wavered. “Because I didn’t become a professional astronaut, I have been looking for other ways,” Ansari said. “So, even before meeting Peter Diamandis, I did a lot of looking around on the Web and other places, trying to see what was happening with the space program and if there would be an opportunity for civilians to fly. I had visited the X Prize website and a couple of other websites where they were advertising for tickets for suborbital flights. I did a little bit more research and found out they were basically just doing a lot of conceptual design of these suborbital vehicles to compete in the X Prize. I believed that it would happen soon enough, and probably my first experience or first chance would be on suborbital flight.”

In 2001, Fortune magazine ran an article about the forty wealthiest people under the age of forty. Ansari made number thirty-three on the list, ahead of Jim Carrey at number thirty-six and Tiger Woods at number forty. But in a sidepiece, Ansari made it clear to the world that space was her number-one goal. There, Ansari had expressed “her desire to board a civilian-carrying, suborbital shuttle.”

“I read that like three times,” Diamandis said. “So, I convinced myself that it really said suborbital flight.”

|

|

г >

Fig. 2.12. Captivated by space from her childhood days, Anousheh Ansari never stopped believing that some day she would make it to space. In 2004, the Ansari family was officially named the title sponsor of the X Prize. Two years later, Anousheh Ansari’s dream came true. Prodea Systems, Inc.

All rights reserved. Used under permission of Prodea Systems, Inc.

V_____________________________________ )

Diamandis and Lichtenberg immediately contacted Ansari to arrange a meeting. “From the first moment we sat across the table and started to talk about it, Peter had us sold,” Anousheh Ansari said, speaking of her and her bother-in-law, Amir Ansari, who had shared the same excitement about space.

Ansari began backing the X Prize in 2002. However, it wasn’t until May 2004 that the Ansari family was announced as the title sponsor. “Our sponsorship was absolutely needed for X Prize to succeed,” she noted. “At the time we joined the organization, if we had decided not to, I don’t know if they would have survived. We felt that we couldn’t let that happen. This was too valuable. It was difficult to put together such a good group of people again. The momentum was right. We couldn’t just let it go. And at the same time, the reason we did it was because we love flying to space. And it wasn’t like I want to do it just once, and we knew there were millions of people around the world that felt the same way. We wanted to do something to help build an industry so this would become something that would be available, and you can do it again and again and again.”