Sixth Story

Let’s go back to the fixing of parameters. Remember: ‘‘If the gust response parameter, G, is fixed to give a certain response level, and the operational Mach number and the aircraft weight are also fixed, then from (1) it is clear that at-S becomes constant.’’ So G and Mare fixed.

Now let’s turn to W So why or how has weight been fixed? This is another paper chase. It takes us to a document that we have come across before:

It is desirable both from the point of view of development time and cost, that a proposed aircraft to any given specification should be as small as possible. For any project study the optimum size of aircraft is obtained by iteration during the initial

design stages. The size of aircraft which emerges from this iteration process is a function of many variables. Wing area is determined by performance and aerodynamic requirements. Fuselage size is a function of engine size and the type of installation, volume of equipment, fuel and payload, aerodynamic stability requirements and the assumed percentages of the internal volume ofthe aircraft which can be utilised. (English Electric/Short Bros. 1958, 2.1.8)

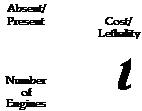

So there are many variables, too many for us to magnify. Let’s stick with engines. For aircraft size (and therefore weight) is not simply a matter of the ‘‘size and type of installation.” It’s also, and even more immediately, a function of the number of engines. Here is OR 339 again: ‘‘The Air Staff require the aircraft design to incorporate two engines’’ (Air Ministry 1958, para. 9). Two engines. But why? Well, we already know the answer because we looked at the English Electric brochure in the previous chapter. Pilots don’t like flying supersonic aircraft with only one engine when that engine fails.9 So the pilots are back again. This time they are not being frightened by oscillation or nauseated, but they are worrying about something else. Another difference that is absent but present: the worry is that supersonic aircraft are more likely to crash, and the OR 339 aircraft has to travel a long way from home.

But there are other possible differences. We know that Vickers Armstrong wanted a single-engine aircraft: ‘‘From the very beginning of our study of the G. O.R. we believed that if this project was to move forward into the realm of reality—or perhaps more aptly the realm of practical politics—it was essential that the cost of the whole project should be kept down to a minimum whilst fully meeting the requirement. This led us towards the small aircraft which, by concentrating the development effort on the equipment, offers the most economical solution as well as showing advantages from a purely technical standpoint.’’10 And these were the arguments: it would sell better; it would be more lethal per pound spent; and it could interest the Royal Navy because they might use it on their aircraft carriers (Vickers Armstrong 1958c, 2-3).

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

![]()

Heterogeneity/Noncoherence

Aircraft safety, pilot worry, the need to fly far from base. This set of considerations tends to fix W at a higher value and thus make the aircraft heavier. Cost, cost-effective lethality, naval use, practical politics, sales, this second set of considerations tends to fix W at a lower value and thus make the aircraft lighter.

So there are two sets of connections, two sets of relations of difference. This is old territory for those who study technoscience. It’s a controversy. As we know, the Air Ministry is going to disagree with Vickers and stick with its large, twin-engine aircraft: ‘‘The reply by D. F.S. to D. O.R.(A)’s request for a study on the single versus twin engined aircraft was received 16th July. It showed fairly conclusively that the twin engined configuration is the less costly in accidents’’ (AIR8/2196 1958b, para. 43).

But if it is a controversy, it is something else too. It is another form of absence/presence. For controversy and disagreement are absent from W. They are absent from the formalism. There is no room for controversy in formalisms. Trade-offs, reciprocal relations, all kinds of subtle differences and distributions yes, but controversies no. And noncoherences not at all.

For, if the arguments about the size of the aircraft, about W, about the number of engines it should carry, are a form of controversy, they are also an expression of noncoherence, dispersal, and lack of connection. For the Air Ministry is talking about one thing while Vickers

|

106 Heterogeneities |

is talking about another: ‘‘We must be perfectly clear as to what is the principal objective of the design. It is to produce a tactical strike system for the use of the Royal Air Force in a limited war environment, or a ‘warm peace’ environment, and should thus be aimed at providing the maximum strike potential for a given amount of national effort. It is not—emphatically not in my view—to produce a vehicle to enable the Royal Air Force to carry out a given amount of peace-time flying for a minimum accident rate’’ (Vickers Armstrong 1958a, 1). Vickers is talking about cost/lethality, and the Air Ministry is talking about accident costs. This is a dialogue of the partially deaf. It is a dialogue in which the ministry decides—in which it ‘‘has’’ the power. But there is something else, a point to do with the absence/presence of noncoherence. For what is present encompasses, embodies, connects, makes links that are absent—except that such links aren’t connections at all. They aren’t connections because they aren’t coherent and they aren’t joined up into something consistent. Except that they are nevertheless brought together, in their noncoherence, in what is present. (Present) coherence/(absent) noncoherence. Like the performance of jokes in Freud’s understanding, noncoherent distribution or interference is a fifth version of heterogeneity. |