Speed/Heroism

As a final example of the working of the strategies of coordination in the brochure, I want to touch briefly on the issue of speed.

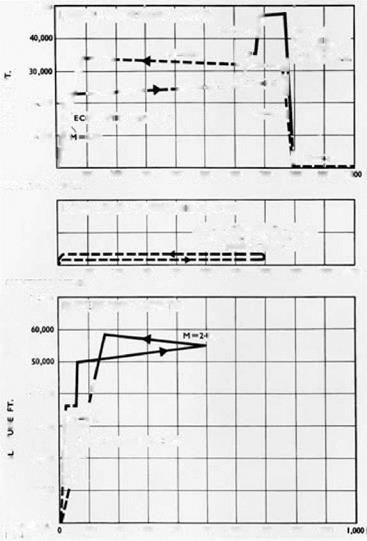

Like exhibit 2.2, exhibit 2.15 deploys syntactical and discursive conventions to create an object that is capable of flying both fast and low. Exhibit 2.16 uses graphing conventions that are somewhat related to those of cartography, both to identify an aircraft that is capable of the long-range missions identified by more direct cartographic means in exhibit 2.11 and again to offer a message about speed. But the making of an object that is singularly fast uses many more conventions, and some of them are much less direct in character. For instance, exhibit 2.1 depicts an aircraft (which we may now agree is the TSR2) from behind and below. Though this is not given in its per – spectivalism, a competent reader will also note the undercarriage is retracted. This means that in the depiction the aircraft is being made to fly, made to move, though it is true that we are given no clues as to how fast it might be moving. But this is not the case for the front cover (exhibit 2.7). Like exhibit 2.1 this is again in part produced by the technologies of perspectivalism. At first sight it might seem that the viewpoint is that of the pilot. But this isn’t quite right because the pilot, confined to his cockpit behind the heavy canopy that protects him, would not enjoy a spectacular all-round view of the kind on offer here. In which case the representation may not so much be what the pilot sees but rather what the aircraft itself can see. Perhaps, then, it is a representation of the view the aircraft would enjoy as it flew at two hundred feet.

I have mentioned perspective, but there is another visual strategy at work here, one that is crucial for performing a distinction between

EXHIBIT 2.15 ”TSR2 is designed to operate at 200 ft. above ground level with automatic terrain following, at speeds of up to Mach 1.1. It is capable of Mach 2 plus at medium altitudes.” (British Aircraft Corporation 1962, 4)

_____________________________________________________________ Objects 29

EXHIBIT 2.16 Sorties (British Aircraft Corporation 1962, 10;

EXHIBIT 2.16 Sorties (British Aircraft Corporation 1962, 10;

© Brooklands Museum)

|

|

0 ИМ ЮС Л» +M SCO MC J«1 MJ ЇСі) I. WO NAUTICAL MILtl |

|

4,000 |

|

Hi n JW 40ft SCO МО KM 8» Wfl |

stasis and movement—and which also tells us the direction of that movement. It works, as is obvious, by blurring many of the lines and surfaces in the visual depiction. The principle is straightforward: as in a cartoon strip all those lines not parallel to the direction of travel are blurred. If the viewpoint itself is traveling, then static objects are blurred. Seen from a static position it is, of course, the other way

round. However, it is the first of these alternatives that is being mobilized here. And since the convention is indeed superimposed on a version of perspectivalism, those lines that are not blurred converge to a vanishing point: the place into which the aircraft will shortly disappear.

As is obvious, there is a connection between all of these exhibits.

All embody strategies for making speed, albeit by different means.

Through these different texts and depictions the TSR2 is being turned into a very fast aircraft. But in exhibit 2.7 something else is going on too. Here speed is being made a relative matter, turned into a question of contrast. A division between movement and statis is being performed. This is implicit in the technology of blurring superimposed onto perspectivalism. This exhibit suggests that the aircraft is only present for a split second. Right now it is, to be sure, above the buildings that are dimly discernible below. But in half a second they will be gone. They will have disappeared as the aircraft itself disappears into the vanishing point.

And what is the significance of this? I offer the following suggestion: we are witnessing not only speed but also a depiction that helps to reflect and perform a particular version of male agency. Thus I take it that the front cover is telling, in a way that the textual and graphing conventions of exhibits 2.15 and 2.16 do not, that this is not just a fast aircraft and one that flies low. We are also being told that it is an exciting aircraft to fly. That it is a thrill to fly. That it is, in short, a pilot’s aircraft.

The creation of speed is not, to be sure, itself a strategy of coordination. Rather, it is an effect of a series of such strategies. It is crucial, however, for all sorts of reasons. Some of these are ‘‘technical’’ in character (to use a term of contrast that I will try to undermine in chapter 6). There are, indeed, technical or strategic reasons for the aircraft to fly very fast and very low. But others are not. Thus I suggest that speed is the raw material on which another effect builds itself: the depiction and performance of heroic agency. In this way it helps to make a particular kind of reader—not simply a ‘‘technical’’ subject who responds to the technical attributes of the TSR2, one who wants to know how far it can fly, whether it can defend the Australian Northern Territory from the Indonesians or the communist Chinese, Objects 31

or whether it can fly under the enemy radar screen. It also helps (and here is the other half of that dangerous contrast) to make a subject that is aesthetic, indeed erotic, one that enjoys fast and even dangerous flying. Thrills and spills: there are coordinating strategies for linking these together. And unless we can generate a reader of this kind from the specificities of the materials of the brochure, then we are, indeed, missing out on something very important about the effects of the strategies for coordinating those different object specificities.13