Naive Readings

Exhibit 2.1 is from page twenty-five of the brochure. As is obvious, this is a drawing, the drawing of an aircraft. Then the question arises immediately: how naive do we want to make the reader? If we insist on a radical version of naivete then we need to say that there is nothing about the picture that links it with the TSR2. For yes, it is a picture of an aircraft. But there is no caption to say that this aircraft is the TSR2.

EXHIBIT 2.1 Perspectival Sketch of Aircraft (British Aircraft Corporation 1962, 25;

© Brooklands Museum)

© Brooklands Museum)

EXHIBIT 2.2 ”The T. S.R.2 weapons system is capable of a wide range of reconnaissance and nuclear and high explosive strike roles in all weathers and with a minimum of ground support facilities.” (British Aircraft Corporation 1962, 4)

EXHIBIT 2.3 ”In T. S.R.2, high grade reconnaissance is allied to very accurate navigation and this suggests the application of the aircraft to survey duties. In many areas the navigation accuracy of better than 0.3% of distance travelled is a significant improvement on the geodetic accuracy of existing maps. This degree of precision enables new maps to be made or old ones to be corrected with a minimum of accurately surveyed reference points.” (British Aircraft Corporation 1962, 17)

Exhibit 2.2 appears much earlier in the brochure—indeed on the first full page of text. Here we don’t learn anything about an aircraft. Instead, we learn that the TSR2 is a weapons system. We also learn that this weapons system fulfills a range of roles, and that it does so in ways that are independent of the effects of weather and elaborate ground-support facilities. But is it an aircraft? Again, to be sure, it depends just how naive we want to be. But ifwe were to dig in our heels then we would have to say that we’ve learned that the ‘‘TSR2’’ is a weapons system, but not that it is an aircraft.

Exhibit 2.3 tells us something about TSR2 and navigation. Here the naive reader does indeed learn that TSR2 is an aircraft, but that reader also learns something about the character of this aircraft: that it has

|

|

EXHIBIT 2.4 ”In T. S.R.2 the internal and external communications facilities are completely i ntegrated. Two control units provi de for i ntercommunicati on between the crew and for control of the radio equipment installed.” (British Aircraft Corporation 1962, 29)

to do with remote sensing and surveying. TSR2, or so it is being suggested here, is an aircraft capable of accurate navigation—but also, and perhaps more remarkably, one that is capable of making maps.

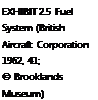

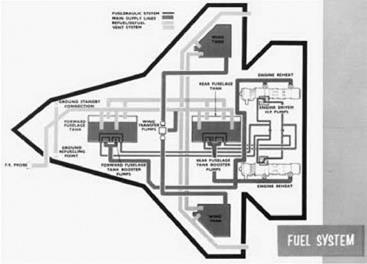

How many more versions of naivete do we need? Exhibit 2.4 turns the TSR2 into a communications system. Exhibit 2.5 (though, like the drawing in exhibit 2.1, it does not mention the TSR2 by name), turns it into a fuel system, complete with pipes, tanks, pumps, and engines. And exhibit 2.6 (again we need to enter the caveat about the absence of a name) turns it into a global traveler, moving to and fro between Britain, Australia, and a host of other points around the globe.

Let’s stop the experiment now. We could pile up more exhibits, but we have learned what we need to learn for the moment: a naive reader who does not start out with an idea of what it is, this TSR2, who does not make connections, will learn that it is many and quite different things.1 Let me stress the point: ‘‘the TSR2’’ is not a single

object; neither, whatever the exhibits might suggest, is it many different parts of a single object. Instead it is many quite different things. It is not one, but many.

This is the problem of difference: we have different objects. Or it is the problem of multiplicity: we have multiple objects. In other words, a reader who insists on being naive is likely to find that he or she is dealing not with a single object but rather with an endless series of different objects, objects that carry the same name—for instance “TSR2’’—but which are quite unlike one another in character.

Of course, we know that it is not really like that. We know—or at least we assume—that the object, the TSR2, is indeed an object. But why is this? Why do we make this jump? And how does it come about? The ability to pose such questions is the reason for avoiding a historian’s sensibility and the justification for being naive. An initial assumption of naivete enables us to ask why the reader for whom the brochure was intended would assume that it was, indeed, describing a single object, a single aircraft, rather than a whole flock of different machines. In other words, an initial assumption of naivete is a methodological position.2

But why be naive? To answer this question I need to talk of strategies of coordination. In particular, I will identify a series of mechanisms that work to connect and coordinate disparate elements. The

|

|

|

|

|

TSR2 brochure, or so I want to suggest, embodies and performs a number of these.