Technological Component: The Software

The term “software” was generally used for the program content of the satellite broadcast. An enormous amount of programming had to be produced for SITE as the satellite was available to India for approximately 1,400 hours of transmission.36 All India Radio, later Doordarshan, took the overall responsibility for producing these programs. The educational programs were produced in three base production centers: Cuttack, Hyderabad, and Delhi. The production of such a large number of programs, keeping in view the basic objectives and the specific audience requirements, was a challenging task. Most of the studio facilities available to SITE were small, underequipped, and understaffed. This fact, coupled with the time pressure for production, created a continuing pressure toward easy-to-produce “entertainment” programming, even when audience feedback indicated a preference for the so-called hard core instructional programs.37 Since the software part demanded a lot of attention from the Indian side Frutkin made every attempt to ensure that it was done properly. “When he visited India in January 1975, seven months before the experiment started, he insisted on a physical examination of television studios and programs.”38

Doordarshan formed separate committees to assist program production relating to agriculture, health, and family planning. These committees were helped by institutions like the agricultural universities, teachers training colleges, the Indian Council of Agricultural Research, and so on.39 Other departments and agencies like the Film Division, the National Center for Educational Research and Training (NCERT) under the Department of Education, along with independent producers, contributed to making film material for the software content of the SITE project. SITE broadcasts regularly reached over 2,300 villages. Their size varied from 600 to 3,000 people, with an average of 1,200 inhabitants. Thus, about 2.8 million people had daily access to SITE programming.40 The programs were available for some four hours a day and were telecast twice, morning and evening.

SITE ended on July 31, 1976. Seeing the success of the project the Indian officials and policymakers requested an extension of the program for one more year, but the request was not granted and ATS-6 was pulled back to the American region.

Frutkin, who orchestrated the SITE project for NASA, said that the one-year experiment proved the possibilities of the use of advanced satellites for mass communication. And he clearly knew that it would bring monetary benefits. “We took the satellite back. What was the consequence? India contracted with Ford Aerospace for a commercial satellite to continue their programs. . . the

BROADCAST SATELLITE BRINGS

BROADCAST SATELLITE BRINGS

EDUCATION TO INDIAN VILLAGE

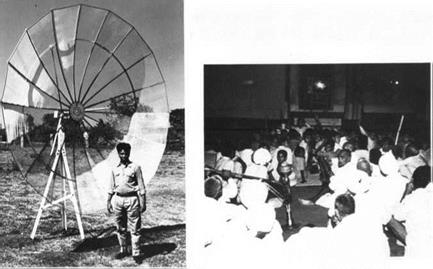

Figure 12.4 ATS receiver and SITE watchers. Source: NASA.

point is, this program not only was an educational lift to India and demonstrated what such a satellite could do, but it brought money back into the U. S. commercial contracts for satellites for a number of years.”41 Years earlier in a House Committee report on the implications of satellite communications, he expressed the same view: “I’m quite confident that by virtue of our participation in this experiment, India will look to the U. S. first for the commercial and launching assistance it requires for future programs. And I think this is a very important product of our relationship.”42

SITE was regarded by many as a landmark experiment in the rapid upgrading of education in a developing country (figure 12.4). It became the most innovative and potentially the most far-reaching effort to apply advanced Western technologies to the traditional problems of the developing world. For the first time NASA and ISRO cooperated very closely in an effort to determine the feasibility of using experimental communication satellite technology to contribute to the solution of some of India’s major education and development needs.43 For NASA the experiment provided a proof that advanced technology could play a major part in solving the problems of less-developed countries. It was seen as an important expression of US policy to make the benefits of its space technology directly available to other peoples and also a valuable test of the technology and social mechanisms of community broadcasting. Seeing Indian states to be linguistically divided, the US State Department hoped that the experiment offered India an important and useful domestic tool in the interests of national cohesion. The experiment also stimulated a domestic television manufacturing enterprise in India with important managerial, economic, and technological implications. It provided information and experience of value for future application of educational programs elsewhere in the world.44

Frutkin was emphatic about the value of SITE for other developing countries. “The Indian experiment is, of course, of prime significance for developing countries, those which have not been able to reach large segments of their population, those which have overriding social problems which might be ameliorated through communication and education and particularly those where visual techniques could help to bypass prevalent illiteracy.”45 The SITE experiment played a crucial role for India too. The results of the year-long SITE project were evaluated carefully by the Indian government. The data played a major role in determining whether India should continue to develop her own communication satellite program (INSAT) or fall back on the use of more traditional, terrestrial forms of mass communication in order to transmit educational programs to the populace.46 Thanks to SITE the first-generation Indian National Satellite (INSAT-1) series, four in total, was built by Ford Aerospace in the United States.47

The SITE project represented an important experimental step in the development of a national communications system and of the underlying technological, managerial, and social supporting elements. Following the proposal made by India, Brazil too initiated a proposal for a quite different educational broadcast experiment utilizing the ATS-6 spacecraft. The project was intended to serve as the development prototype of a system that would broadcast television and radio instructional material to the entire country through a government – owned geostationary satellite.48 Frutkin saw the Indian project and the Brazilian experiment to be a model for other developing countries. In 1976 Indonesia became the first country in the developing world to have its own satellite system, the Palapa satellite system, manufactured by engineers at NASA and at Hughes Aerospace.49

SITE showed India that a high technology could be used for socioeconomic development. It became one justification for building a space program in a poor country—the question became “not whether India could afford a space program but can it afford not to have one”?50 “Modernization” through science and technology was not new to the Indian subcontinent. In more than two centuries of British occupation India witnessed a huge incursion of technologies—railways, telegraph, telephone, radio, plastics, printing presses for “development” and extraction.51 The geosynchronous satellite in postcolonial India can be seen as an extension of the terrestrial technologies that the British used to civilize/ modernize a traditional society. In this case the United States replaced the erstwhile imperial power to bring order, control, and “modernization” to the newly decolonized states through digital images using satellite technologies that were far removed from the territorial sovereignty of nation-states.52