Winning Hearts and Minds

SITE offered the State Department twin benefits: a benign technological tool to offset communist China’s influence, and a technology that would help to bring literacy and development to the rural population. This was perfectly in line with what the communication scholars and media experts were promoting in the early 1960s, the idea that television and other media of mass communication would help national development. Stalwarts in communication and development studies such as Daniel Lerner, Wilbur Schramm, and Everett M. Rogers based their theories of development and media efficacy on Walt Rostow’s influential Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto.19 In the book Rostow stressed that the economic and technological development achieved by the Western nations were the result of increased media use. If the developing countries could follow the path of modernization initiated by the West, they would leapfrog centuries of inaction and underdevelopment and catch up with the modernized West.20 Rostow who later became the national security adviser to President Lyndon Johnson, was himself interested in putting “television sets in the thatch hutches of the world” to defeat both tradition and communism with the spectacle of consumption.21 The political value of communication satellites was also emphasized by Arthur C. Clark:

Living as I do in the Far East, I am constantly reminded of the struggle between the Western World and the USSR for the uncommitted millions of Asia. The printed word plays only a small part in this battle for the minds of the largely illiterate population and even radio is limited in range and impact. But when line of sight TV transmission becomes possible through satellites directly overhead, the propaganda effect may be decisive. . . the impact upon the peoples of Asia and Africa may be overwhelming. It may well determine whether Russian or English is the main language of the future. The TV satellite is mightier than the ICBM.22

India was particularly appropriate for a satellite experiment in the direct broadcasting of TV. First, there was no existing TV distribution network, which could be utilized by conventional means. The population was distributed relatively homogeneously throughout the subcontinent rather than concentrated in a few large cities easily reached by conventional TV, and there was a high level of Indian government support for this kind of experiment. This contrasted with other developing countries, for instance, Brazil. There, a substantial portion of the population was concentrated in coastal cities, all of which already possessed TV networks, while only the scattered inland population lacked TV. So, India stood apart as an ideal laboratory for testing the technology. Wallace Joyce, in the International Scientific and Technological Affairs of the State Department, particularly liked Webb’s idea. It had the potential for India to exert “regional leadership” in space-related educational TV for development purposes in the surrounding Asian and other modernizing regions.23

For Frutkin, the instructional television project was a constructive step forward in cooperation between one of the world’s superpowers and a progressive, neutral, developing nation. “For other developing countries, it should serve on a non cost basis to test the values, the feasibility, and the requirements of a multi-purpose tool which could be critical to accelerating their progress in an increasingly technological world.”24 There is “some measure of generalization, hyperbole, and technological misconception” when it came to direct broadcasting of television, remarked Frutkin. In order to realistically consider the problems and technological hurdles associated with direct broadcasting he sought an “actual experience

|

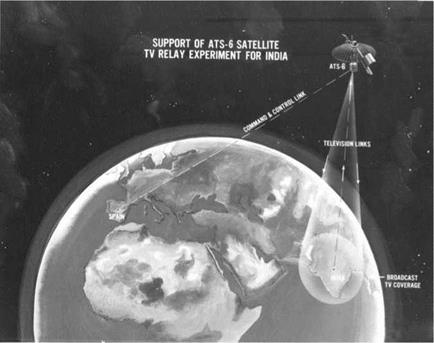

Figure 12.2 Artist’s conception of ATS-6 support. Source: NASA. |

with the medium.” The experiment represented a “rarely grasped opportunity to use modern technology so as to leapfrog historical development stages.”25

The Indian space experts too were interested in exploring the potentialities of TV as a means of mass communication in a developing country. In 1967, only Delhi, the capital city of India, had television transmission services. The Indian broadcast planners organized under the Ministry of Information and Public Broadcasting (MIPB) wanted to extend the television services by first focusing on the cities and gradually extending it to rural villages through transmitters. Seeing the cities to be already “information rich” through various other media, Vikram Sarabhai, in contrast to the broadcast agency—which blamed the space agency for unnecessarily encroaching on their domain—wanted the villages to receive the high technology first. In June 1967 Sarabhai sent a team to NASA to study the prospects of using a satellite over a conventional transmission links. After looking at various options, the visitors focused in on a “hybrid system for rebroadcast stations for high population areas, and a satellite for interconnection and transmission to low-population density areas.” The interaction between NASA, Indian actors, and the business corporations in America planted the seed for the Indian National Satellite (INSAT), which was developed during the early 1980s.26

To test the efficiency of such a massive system for the entire Indian population officials at NASA and the State Department conceptualized a limited one-year SITE project using the ATS-6 satellite (figure 12.2). The SITE project was not without domestic resistance, however. To reach a consensus among different agencies Sarabhai set up an ad hoc National Satellite Telecommunications Committee (NASCOM) in 1968. SITE was finally approved after an extensive debate in the parliament.

An agreement was signed between NASA and ISRO in 1969 wherein NASA agreed to provide this satellite for one year. NASA would provide the space segment while ISRO took charge of the ground segment and programs. NASA helped ISRO by offering training facilities to its engineers at different NASA facilities and by helping in the procurement of critical components when these were urgently required at short notice. Numerous ISRO-NASA meetings held in India and America helped sort out interface problems and in acquainting each other with the progress of the SITE project. In order to plan the for the year-long project, the Indian space agency undertook a small experiment called Krishi Darshan (Agricultural TV Program). Around 80 television sets were placed in rural villages around Delhi to test “software development, receiver maintenance, and audience information utilization.”27 To prepare for the future, joint studies were also done by ISRO engineers with NASA and private corporations such as Hughes Aircraft, and General Electric for configuring systems for INSAT. In 1970, ISRO engineers undertook a study at Lincoln Labs at MIT for spacecraft studies of INSAT. Sarabhai planned INSAT as a follow on after the SITE experiment.28