THE CONSPIRACY

In contrast to the low priority assigned to the military space station projects at the overcommitted TsKBEM, the Ministry of Defence encouraged the development of Chelomey’s Almaz. Although this project suffered protracted delays, by 1969 it was the only real Soviet space station project. It is true that there were ideas for joint endeavours in space station development between Mishin’s team in Kaliningrad and Chelomey’s in Reutov, but owing to the poor relationship between the two Chief Designers no one at the TsKBEM wished to approach Mishin officially to propose a formal collaboration. Even the Kremlin recognised that rivalry between the bureaus had seriously damaged the Soviet space programme. Once, even the mighty Ustinov said that Mishin and Chelomey behaved just as if the bureaus were their personal ‘‘principalities’’. Although the Kremlin could have ordered strategic integration, in practice it did little to force the bureaus to collaborate.

In the meantime, the Americans had been very busy. In August 1965 NASA had assigned a group of experts the task of defining a programme of long-term scientific research in Earth orbit using Apollo hardware. This drew up a phased programme that would lead to a scientific space station. Over the years most of these projects were dismissed, but in the spring of 1969 it was announced that a ‘Sky Laboratory’ (Skylab) would be launched in 1972. It would be a 90-tonne giant, and with a length of 36 metres and a diameter of 6 metres it would have a volume of 400 cubic metres – four times that of Almaz. The pace of the American space programme renewed the Kremlin’s concern. It was clear that the USSR had lost the race to land a man on the Moon, work on the Almaz space station was seriously behind schedule, and all that the TsKBEM had to offer was the Soyuz spacecraft. The Soviet response to the American plan would therefore have to be quick and efficient.

In August 1969 a group of designers led by Boris Raushenbakh, the TsKBEM Department Chief responsible for the development of spacecraft guidance systems, put it to Boris Chertok, their boss, that a propellant tank of the Soyuz rocket should be converted into a space station. It was estimated that this could be done within a year, and could be launched before Almaz – and before Skylab, of course. As the Chief Designer, Mishin was the top man. His First Deputy was Sergey Okhapkin,

who was in charge of the development of rocket systems, including the N1 launcher. Next was Konstantin Bushuyev, the Deputy Chief Designer for the development of unmanned and manned spacecraft, including the Soyuz spacecraft and its L1 and L3 variants. Deputy Chief Designer Chertok was the fourth man, and his responsibility was the development of guidance, control and electrical systems for launchers and spacecraft. Chertok was one of the pioneers of Soviet rocketry, having worked with Korolev and the other leading Soviet rocket designers in analysing the design of the V-2 rockets that were confiscated from the Nazis. Raushenbakh had left Keldysh’s tutelage to join Chertok’s group in the early days of OKB-1, and was one of the few top Soviet spacecraft designers whose name was known in the West. His proposal was to modify a tank to accommodate various systems from a Soyuz spacecraft, and to install solar panels, a docking mechanism and a hermetic tunnel to provide access from a docked Soyuz. The fact that this structure was to be launched by the Proton rocket meant that its mass could be no greater than that of Almaz, but it would be much simpler.[22]

Initially, Chertok hesitated. His main concern was the limitations implicit in the systems developed for the Soyuz spacecraft. An additional issue was that a vehicle having three times the mass of the Soyuz would require more powerful engines to maintain its orbit and to control its orientation. Furthermore, this propulsion system would require to be able to support a mission of many months, rather than a brief Soyuz flight. Chertok consulted his old friend Aleksey Isayev. In 1944 Isayev had been appointed the Chief Designer of OKB-2 (in 1966 renamed Himmash), and had worked with Chertok and Korolev in Germany. He was now the leading designer of rocket engines for both unmanned and manned spacecraft. When Chertok explained the TsKBEM’s idea, Isayev said that he had already developed such a propulsion system for Chelomey’s Almaz. The logical way to proceed would be to combine the proven systems of the Soyuz spacecraft with those already developed for the Almaz station. Thus was born an idea with dramatic implications for the future of world cosmonautics.

Interestingly, only a small group were involved in originating this project. Taking the lead was Konstantin Feoktistov. As a Department Chief in Bushuyev’s group, he was of similar rank to Raushenbakh. He had been involved from the earliest days in the design of the Vostok spacecraft, and in return for leading the modification of that capsule to accommodate three cosmonauts he had been assigned to the crew of the first Voskhod flight in October 1964. The Soyuz spacecraft was very much one of his ‘offspring’. On hearing of the proposal to convert a propellant tank into a station, Feoktistov asked: why start with an empty tank? There were several Almaz prototypes standing idle in Chelomey’s factory in Fili. It would be better to modify one of these.

However, Chelomey was sure to oppose any attempt to requisition his spacecraft, the Ministry of Defence and Minister Afanasyev would reject any further delays in Almaz development and, of course, Mishin would not appreciate a proposal to use a

|

The development of the Soyuz spacecraft was led by Department Chief Konstantin Feoktistov. |

competitor’s hardware in a TsKBEM project. But Feoktistov and Chertok thought differently. Their strategy was to avoid anyone who might raise an objection, and to go straight to Dmitriy Ustinov, who was on the Central Committee of the Kremlin and was in overall control of the Soviet space programme. They were sure he would understand the strategic implications of the idea. However, it was no simple matter to contact Ustinov. Normally such an approach would be made by Mishin, as head of the bureau. But Mishin was in Kyslovodsk, taking his annual leave; and anyway he would object. In Mishin’s absence, Bushuyev was one of the few people with the authority to seek a meeting with Ustinov.

Feoktistov recalls: “Several times Bushuyev, Chertok and I reviewed this matter. Chertok, and his engineers who’d worked on the development of guidance systems, supported the idea of moving immediately. But Bushuyev hesitated because Mishin would be against the idea, and we would not have the support of our own bureau.’’

Someone suggested that Bushuyev should call Ustinov and ask for a meeting, but Bushuyev did not wish to take such an important step without the knowledge of his bureau chief. However, Feoktistov had a reputation for being disobedient, and he proposed that he call Ustinov. Intriguingly, although Feoktistov was not a member of Communist Party, he readily arranged a meeting with one of the most influential men in the Central Committee.

Ustinov was aware that even under the most optimistic scenario, Almaz would not be ready until early 1972. If everything went to plan Almaz would beat Skylab, but if the launch were to fail, or if the station were to experience a problem that would prevent a crew from boarding it, then the Soviet Union would again trail behind the Americans. Another issue was that as a military project, the design and operation of the Almaz station should remain a secret. Skylab was a scientific project funded by NASA. If the first Soviet space station could be portrayed as a civilian space project, and it was given lavish coverage in the newspapers, then it would serve to mask the true role of the subsequent Almaz stations – about which much less information would be released. That is, to launch a scientific station first would serve as a maskirovka, or deception, designed to hide the real project. Ustinov fully appreciated this point. He invited Chertok, Bushuyev, Feoktistov, Raushenbakh and Okhapkin to his office on 5 December 1969. Also present were Leonid Smirnov, who was Aleksey Kosygin’s deputy for space matters and chairman of the VPK since 1963, Afanasyev, Keldysh and some of Ustinov’s officials. As Mishin was on vacation it was reasonable that he should not be invited, and Chelomey, being in hospital, was conveniently unavailable.

In advance of the meeting, the TsKBEM people agreed to let Feoktistov talk first. His presentation was very convincing. It would be possible to equip the core of one of Chelomey’s stations with the solar panels of the Soyuz spacecraft, together with its guidance and command systems. In approximately a year’s time, Feoktistov said, the Soviet Union would have the world’s first space station. Chertok then noted that the systems of the Soyuz spacecraft were considered to be reliable because they had been tested during 14 unmanned and manned orbital flights. The development of a docking system incorporating an internal tunnel was underway. Keldysh asked how the construction of such a space station would interfere with the development of the N1-L3 lunar programme. Okhapkin said that the two projects were separate, and the designers involved in the lunar programme would not be needed for the station. Of course, Ustinov knew that both Soviet lunar programmes were under review. After the success of Apollo 8 in December 1968 the L1 circumlunar project launched by a Proton rocket had lost its purpose, and the N1-L3 lunar landing was contingent on successfully introducing the N1 launch vehicle – and after two spectacular failures in January and July 1969 some people were beginning to doubt that this would ever fly. And then, of course, the Americans had already won the race to the Moon.

Ustinov was enthusiastic about the space station conversion, not only because if it worked it would demonstrate that the Soviet Union was ahead of the Americans in this aspect of manned spaceflight, and not only to provide a maskirovka for Almaz, but also because Ustinov had never liked how Chelomey had exploited the personal support of Khrushchov and his links with the Kremlin and the Ministry of Defence

|

|

|

|

The N1 lunar rocket was Vasiliy Mishin’s dream. |

to expand his activities into manned spacecraft. Ustinov wanted all such work to be undertaken by a single design bureau. Converting the core of a military Almaz into a civilian space station would not only enable the Soviet Union to once again claim leadership in space, it would also put Chelomey in his place!

The meeting ended with the decision to immediately prepare a project time-scale, and by the end of January 1970 to issue a decree to endorse the plan. Although the TsKBEM rebels were surprised by the ready acceptance of their proposal, they had (to coin a phrase) been ‘pushing an open door’. Brezhnyev accepted the importance of space stations for national prestige. In fact, he had referred to them several times in speeches which he made that autumn, and on 22 October, in welcoming home the crews of the ‘group flight’ of Soyuz 6, 7 and 8, he had asserted that the USSR had a broad space programme which was planned years in advance and would unfold in a logical manner. The strategy was to downplay American successes and not to admit Soviet failures. This was why the USSR was only one of two European states (the other being Albania) not to run ‘live’ TV coverage of the first manned lunar landing. In order to convey the impression that the Soviet space programme was following a grand plan, Brezhnyev had spoken of ‘‘space cosmodromes” from which men would set off on journeys to the planets. Obviously, however, this plan would unfold by a series of ever more ambitious steps, the first of which would be relatively modest. By the end of November 1969 Academicians Keldysh and Boris Petrov had written in newspaper articles that space stations would permit unprecedented monitoring of meteorology, oceanology, ecology and aspects of the economy; they would serve as laboratories to study physics, geophysics, advanced technology and astronomy; they would serve as factories; and later they would test systems needed by the promised interplanetary spaceships.

|

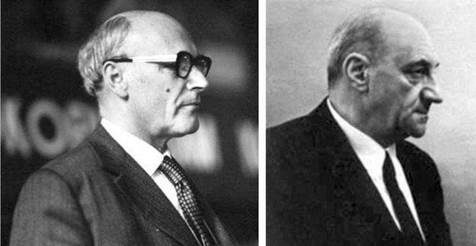

Space stations and the Kremlin. Kosygin (left) and Brezhnyev (second right) with the crew of Soyuz 9: Sevastyanov and Nikolayev. |

DOS IS BORN

Although Mishin and Chelomey were united in their opposition to the plan to create a hybrid Long-Duration Orbital Station (DOS) by using Almaz and Soyuz systems, the Kremlin’s directive was firm. Chelomey was satisfied to ensure that this project would not further delay Almaz, but Mishin was furious at what he referred to as the “conspiracy”. In one meeting Mishin threatened: “If I hear that anybody else apart from these two – Bushuyev and Feoktistov – occupies himself with this DOS, I will send him to hell.’’ He opposed the DOS effort not only because his staff had gone behind his back to initiate it, but also out of concern that, despite assurances to the contrary, it would jeopardise the N1-L3 programme. Even once it was underway he never really endorsed the project, and at times he openly criticised it.

Not only were the TsKBEM designers eager to develop the hybrid space station, so too were the engineers in Fili who had spent five years designing the systems for Almaz and wished to find out how well they performed in space. In fact, Chelomey himself was not very popular in Fili. Initially, Fili had been an independent design bureau (OKB-23) headed by the famous Chief Designer Vladimir Myasishchev, and between 1951 and I960 had created the successful M-4 and 3M strategic bombers. While it was designing the M-50 jet bomber and a manned rocket plane, Chelomey, with the support of Khrushchov, but against the will of the Air Force, had drawn the bureau into his own organisation, naming it Branch No. 1. Myasishchev had gone to the Moscow Aviation Institute. The DOS project provided an opportunity for Fili to regain a degree of autonomy, and Viktor Bugayskiy, who was in charge there, was keen to collaborate with his TsKBEM counterparts.

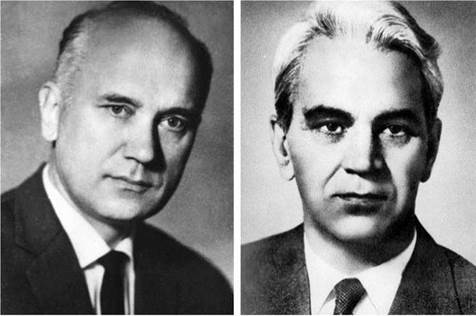

In fact, the first task was to establish a genuine management structure that would integrate the Kaliningrad and Fili design teams. In December 1969, shortly after the meeting with Ustinov, Okhapkin, Bushuyev and Chertok asked Mishin to nominate Yuriy Semyonov as the Leading Designer for the DOS programme. Semyonov had participated in the design of the Soyuz spacecraft and managed the L1 circumlunar programme, whose cancellation was imminent. Semyonov was also a son-in-law of Andrey Kirilenko, the fourth man in the Kremlin’s hierarchy. Although it is only a supposition, it is possible that Ustinov played a role in the nomination; the rationale being that someone with Semyonov’s connections ought to be able to counter any attempts by either Mishin or Chelomey to undermine the rapid pace set for the DOS development. On 31 December the basic organisational documents were drawn up. In January 1970 Mishin officially appointed Semyonov and three deputies: Dmitriy Slesarev was responsible for modifying the Soyuz for use as a space station ferry;[23] Valeriy Ryumin was responsible for the station’s systems; and Viktor Inelaur was responsible for the guidance apparatus. Later, Arvid Pallo was appointed as a fourth deputy. Also, Mishin nominated his own deputies as general managers of the entire programme. Bushuyev, assisted by Feoktistov, was responsible for the development of all aspects of the programme. Under their direct control were Pavel Tsybin, who

|

Yuriy Semyonov led the development of the DOS space station at the TsKBEM. |

managed the development of the Soyuz, and Leonid Gorshkov, the designer of the Orbital Block (i. e. the station itself). In addition, Chertok led the guidance group, with Raushenbakh and Igor Yurasov as deputies; Lev Vilnitskiy was responsible for the docking systems; Vladimir Pravetskiy was responsible for life support systems; Oleg Surgachov was responsible for thermal regulation systems; Yakov Tregub and his deputy, Boris Zelenshchikov, were responsible for the testing of all the systems, cosmonaut training and mission control; Gherman Semyonov was to supervise the preparation of the station for shipment to the cosmodrome; and Aleksey Abramov and Vladimir Karashtin were to manage the launch preparations. In Fili, Bugayskiy nominated Vladimir Pallo as his deputy for the DOS project. This was a wise choice, because when Semyonov added Arvid Pallo to his team the two brothers were well placed to coordinate joint activities. All the leading people of the DOS project have been named here because, by managing the activities of thousands of engineers, technicians and others, they defined the basis for not only the Soviet manned space programme but also, in the long term, the world’s manned space programme.

On 9 February 1970 the Central Committee and the Council of Ministers issued decree No. 105-41. It was one of the most important decrees in the history of space station development. One of its directives was that all pertinent documentation and all existing hardware, including Almaz cores, be transferred to the DOS programme.

After studying the design documents, Feoktistov drew up the specifications of the station to maximally exploit the capabilities of the Proton launcher: it was to have a maximum diameter of 4.15 metres, a length of 14 metres and an initial mass of 19 tonnes. With a volume of almost 100 cubic metres, which was almost ten times that of the Soyuz, it would be able to accommodate comfortable facilities for the crew,

consumables for a long mission and a wide variety of apparatus. One of the design requirements was that most of the built-in apparatus must be accessible to the crew for maintenance, repairs or replacement. In fact, this requirement became one of the greatest design challenges. The complexity of the DOS station is evident from the fact that it had 980 instruments (according to another source 1,300) connected by in excess of 1,000 cables that had a total length of 350 km and a mass of 1.3 tonnes!

The next big decision was the maximum possible operating life of the first station, designated DOS-1. This would depend on the altitude of the orbit, the available fuel and the power supply. Although the upper atmosphere is exceedingly rarefied, if the station were to start off in the range 200-250 km the drag would cause the orbit to decay at an increasing rate, until the station re-entered and was destroyed. It would be necessary to fire the rocket engine periodically to maintain the desired altitude. It was calculated that it would be necessary to use about 3 tonnes of fuel annually to maintain DOS-1 at an altitude of 300 km, 1 tonne at 350 km, and a mere 200 kg at 400 km. A higher orbit was therefore desirable to maximise the operating life of the station. However, the higher the station’s altitude, the more fuel the Soyuz would use to make a rendezvous. Furthermore, a higher altitude would expose the crew to more intense space radiation. The next big issue was the total period of occupancy. This would be dependent on the reserves of air, water and food. Since one man would consume about 10 kg of materials per day, it was decided to load the station with sufficient stores to support three men for three months – a period that would be accumulated by a succession of crews. It was on the basis of such analyses that the documentation for the DOS-1 station was drawn up in February 1970.

The first meeting between the TsKBEM and TsKBM experts was in March 1970. Feoktistov presented the technical specifications to the Fili team. Then Semyonov outlined the structure of the programme, its management, and the responsibilities of not only the TsKBEM and the TsKBM but also their subsidiary factories. The M. V. Khrunichev Machine Building Plant (ZIKh), which the TsKBM managed, was to be responsible for building the DOS stations and the Proton rockets that would launch them. The Plant for Experimental Machine Building (ZEM) had been part of the TsKBEM since 1966, and its role would be to test the station’s apparatus. Because each institution had its own structure, work philosophy, methodology and standards, the task of coordination was formidable. If prior experience was anything to go by, designing, developing, testing and launching a space station would take at least five years, but the DOS managers set out to do so in a period of approximately one year!

The first challenge was to arrange the transfer of the Almaz cores to the TsKBEM. Several days after the first meeting between the two engineering teams, Semyonov went to see Chelomey in Reutov. It was a difficult and strained meeting. Although Semyonov was armed with the Kremlin’s decree, Chelomey accused the TsKBEM of “stealing’’ his work. Only after a telephone call to Afanasyev was Semyonov able to persuade Chelomey to transfer four Almaz cores.[24]

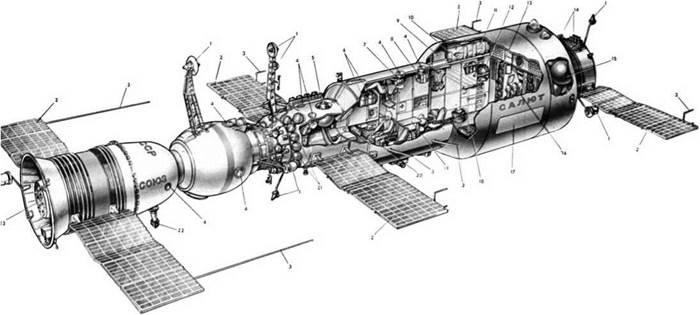

![]() The first DOS space station and a docked Soyuz ferry: (1) rendezvous antennas; (2) solar panels; (3) radio-telemetry antennas; (4) portholes; (5) the Orion astrophysical telescope; (6) the atmospheric regeneration system; (7) a movie camera; (8) a photo camera; (9) biological research equipment; (10) a food refrigeration unit; (11) crew sleeping bags; (12) water tanks; (13) waste collectors; (14) attitude control engines; (15) propellant tanks for the KTDU-66 main engine; (16) the sanitary and hygienic systems; (17) micrometeoroid panel; (18) exercise treadmill (not shown, but it was aft of the large conical housing for scientific equipment viewing through the floor); (19) the crew’s work table; (20) the main control panel; (21) oxygen tanks; (22) the periscope visor of the Soyuz descent module; (23) the KTDU-35 main engine of the Soyuz spacecraft. The conical housing for the main scientific equipment is not shown.

The first DOS space station and a docked Soyuz ferry: (1) rendezvous antennas; (2) solar panels; (3) radio-telemetry antennas; (4) portholes; (5) the Orion astrophysical telescope; (6) the atmospheric regeneration system; (7) a movie camera; (8) a photo camera; (9) biological research equipment; (10) a food refrigeration unit; (11) crew sleeping bags; (12) water tanks; (13) waste collectors; (14) attitude control engines; (15) propellant tanks for the KTDU-66 main engine; (16) the sanitary and hygienic systems; (17) micrometeoroid panel; (18) exercise treadmill (not shown, but it was aft of the large conical housing for scientific equipment viewing through the floor); (19) the crew’s work table; (20) the main control panel; (21) oxygen tanks; (22) the periscope visor of the Soyuz descent module; (23) the KTDU-35 main engine of the Soyuz spacecraft. The conical housing for the main scientific equipment is not shown.

The DOS-1 station will be described in detail later, and here it is necessary only to explain how it differed from Almaz. The transfer compartment housing the docking system was at the front of DOS-1, rather than at the rear. Whereas on Almaz there was a hermetic tunnel through the unpressurised propulsion module, in the case of DOS-1 the docking system provided access to a small compartment that had been added to the front of the Almaz structure. On the exterior of this compartment were two solar panels of the type developed for the Soyuz spacecraft. A hatch led to the compartment which combined the Almaz crew and work compartments.[25] As in the case of Almaz, the rear of the main compartment was dominated by a large conical housing, but now the apparatus was for scientific rather than military observations. Another change was that the propulsion system developed for Almaz was discarded, and a system based on that of the Soyuz spacecraft was affixed in its place. This unit carried a second pair of solar panels.

The following DOS-1 systems were taken from Soyuz spacecraft:

• guidance and orientation

• solar panels

• Zarya radio-equipment

• RTS-9 telemetry system

• Rubin radio-control system

• command radio lines

• central post and main control panel

• Igla rendezvous and docking, and

• regenerators for oxygen.

In addition, the system for controlling the complex was taken from the Soyuz, but it was modified to take account of the station’s greater mass. The thermal regulation system had also to be upgraded. These were in-house systems to the TsKBEM. The

|

A model of a Soyuz spacecraft (left) about to dock with the first DOS space station. The conical housing for the main scientific equipment has been ‘airbrushed out’. |

|

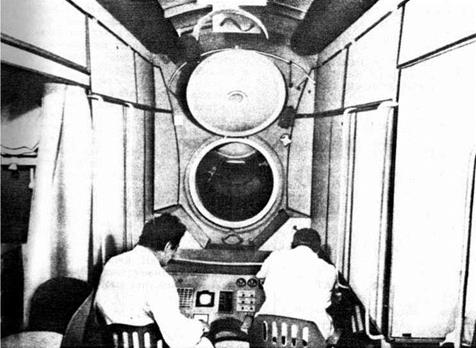

Two engineers work at the main control panel of the DOS station, with the open hatch to the transfer compartment in the background. |

Sirius system for information analysis was supplied by Sergey Darevskiy’s Special Design Bureau. It was based on the Soyuz command display, and on DOS-1 it was on the left-hand side of the main control panel, in front of the commander’s seat. It provided the following indicators:

• the pressure in the fuel tanks

• the distance and speed of the station relative to an approaching spacecraft during rendezvous and docking

• the voltage and current in the electrical power system

• the environmental parameters inside the station

• onboard clocks, and

• a globe to enable the cosmonauts to readily determine the position of the station in relation to terrestrial geography.

The development of the various scientific and medical apparatus also challenged the designers. Never before had so many scientific instruments been installed in one spacecraft: this apparatus weighed 1.5 tonnes in total. Most of it was designed and developed outside the TsKBEM, in coordination with the Academy of Sciences. For example, the Orion ultraviolet telescope was devised by the Byurakan Observatory and the OST-1 solar telescope by the Crimean Observatory. For each instrument on the station, the mission planners had to develop a programme of experiments for the crew to conduct.

Everyone involved in the project worked without holidays in order to build, test and launch the first space station within a period of one year! The project itself, and all the basic systems, were developed by Kaliningrad. Design schemes and system diagrams were prepared by Fili. The manufacturing process was organised by ZEM, where Ryumin and Pallo, Semyonov’s deputies, worked alternate shifts around the clock. The station and its mockups (including wooden ones) were fabricated in the Khrunichev Plant. The final testing of the station was planned and conducted by the TsKBEM.

Even more remarkably, this coordinated effort was conducted without the support – and indeed against the wishes – of the leaders of the two design bureaus: Mishin and Chelomey!

In December 1970, after less than a year, Khrunichev completed the construction of the DOS-1 station. It was transferred to the TsKBEM for further testing, and then delivered to the Baykonur cosmodrome in March 1971.

Specific references

1. Chertok, B. Y., Rockets and People – The Moon Race, Book 4. Mashinostrenie, Moscow, 2002, pp. 239-249 (in Russian).

2. Afanasyev, I. B., Baturin, Y. M. and Belozerskiy, A. G., The World Manned Cosmonautics. RTSoft, Moscow, 2005, pp. 224-226 (in Russian).

3. Afanasyev, I. B., Unknown Spacecrafts. Znaniye, 12/1991 (in Russian).

4. Semyonov, Y. P., ed, Rocket and Space Corporation Energiya named after S. P. Korolev. 1996, pp. 264-269 (in Russian).