The Science in Hubbles Iconic Pictures

Kessler explains that some astronomers were initially dismissive of Hubble’s “pretty pictures.” They felt such images had less to do with science and that the public would accept the false color photos as what Hubble actually sees. But as Kessler points out, Hubble was the vehicle for changing this perception, particularly in the case of the stunning images of the Eagle Nebula (M16) released in 1995 (plate 20). A group of astronomers at Arizona State University led by Jeff Hester were interested in photo-evaporation, by which they suggested radiation from a massive star in the nebula is evaporating gaseous material away from sites of newly forming stars. Kessler notes that Hester’s team “did not plan the observation with the intention of creating a visually impressive picture.”27 However, their remarkable image of the Eagle Nebula awed scientists and general audiences alike. And, as anticipated, in the nebula’s 10-trillion-kilometer gaseous columns, Hester’s team identified regions of newly forming stars.

Upon release of the Eagle Nebula images, Kessler reports, “The New York Times, Washington Post, USA Today, and other major newspapers printed articles featuring the image, and Newsweek, U. S. News and World Report, and Time all ran stories in the following weeks.”28 Kessler highlights the fact that while the news reports detailed Hester’s theory regarding new star formation, the real emphasis of the news coverage was the spectacular beauty of the cloud pillars in the Eagle Nebula, subsequently dubbed the “Pillars of Creation.” A report in 1999 on Hubble’s popularity by the Space Telescope Science Institute indicates that “web hits at the time of the M16 release were about a half a million a month.”29 The fascination with Hester’s image of the Eagle Nebula demonstrated that stunning astronomical photos could capture both important scientific data and amazing spacescapes that readily communicate complex information to general audiences. Kessler points out that NASA quickly realized the tremendous public support for Hubble might be better served through an organization that would regularly request, produce, and release images taken by Hubble. The Hubble Heritage Project emerged out of such interest.

Commenting on what he and members of the Hubble Heritage Project were looking for in the composition of spectacular photos like that of the Eagle Nebula, Jeff Hester explains:

I want [people] to realize, when they look at images like that, that what they are looking at is humans acting on this urge within us. Going out there and proactively building the technology and the tools that allow us to reach out with our minds and our aesthetic and our imaginations and our sense of wonder and our sense of curiosity. . . . That these [photographs] are not just nicely aesthetic, but. . . testaments to what we as people are able to do. To take images of columns of clouds of gas and dust several thousand light years away in which stars are forming, and to bring them home and to make that part of the universe known to us, to extend the sphere of the human mind and imagination out to encompass those things.30

Hester nevertheless understands the difficulty in communicating complex scientific information:

[Science] demands a rigorous vocabulary, the vocabulary of mathematics. It demands that you learn to think in that vocabulary. That’s not a vocabulary that’s accessible to a lot of people. . . . [I]t really matters that you find a way to get around the vocabulary problem, that you find a way to bother to think about who it is that you’re talking to, what is it that they are familiar with . . . [so] that instead they can start to get their arms around [it] a little bit.31

The Hubble Heritage Project’s home page provides thumbnails of approximately two hundred images; these are the best of the best from among tens of thousands of images taken by the facility.32 According to Kessler, the project was the brainchild of planetary scientist Keith Noll and astronomer Howard Bond. Along with Anne Kinney and Carol Christian, these scientists collaborated to create Hubble Heritage images to promote public education and general interest in astronomy and space science. Kessler contends that they have expertly achieved these goals by blurring the boundaries between art and science to contribute to both astronomical investigation as well as popular understanding of cosmology. Keith Noll summarizes the project’s objective:

“[M]y real hope for this is that there are kids that have our pictures on their walls, that maybe spend some time dreaming about what it’s like to be in space, what it would be like to travel to these exotic places. . . . But what I really hope is that they all sort of carry this little bit of awe and mystery with them in their lives, so that everything isn’t just about getting up and driving in traffic and paying bills. It kind of helps to remember. . . how amazing the universe is.33

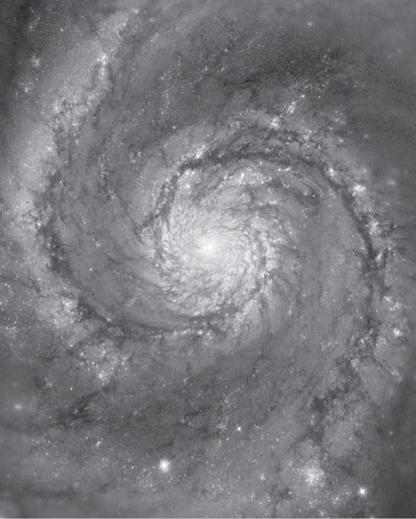

Hubble’s photos easily convey some of the most fascinating aspects of star birth and death, and solar system formation. In many cases it doesn’t require specialized or scientific training to immediately grasp the import of some of Hubble’s most remarkable images. This is true for the Hubble photos of the Eagle Nebula and its collapsing gases in star birth regions, the newly forming star systems in the Orion Nebula (M42) with its proto-planetary disks the size of our Solar System, the star birth visible in the arms of the Whirlpool galaxy as illustrated in the mosaic of M51 (figure 11.2), or the bizarre and complex cloud formations produced by dying stars at the heart of planetary nebulae.

Perhaps the simplest reason for the Hubble telescope being so cherished is that in a single bound, complex scientific investigation can be conveyed in a handful of amazing images. The tremendous energy radiated as stars blow off their gaseous outer layers is evident at a glance from a single image. While the average person may not have imagined the import of a star’s magnetic field in shaping planetary nebulae, the effects of intense radiation and stellar winds are nearly palpable in such photographs. In images with less obvious information, a simple caption can make the meaning immediately comprehensible to the nonspecialist. A short caption regarding the pillars of dust in the Eagle Nebula towering to 10 trillion

|

Figure 11.2. M51 is a nearby spiral galaxy called the Whirlpool galaxy; this is how the disk of the Milky Way would appear if we could gaze down on it, rather than being embedded in the disk. A nearby companion galaxy is triggering intense star formation in the spiral arms. Hubble Space Telescope can resolve individual bright stars in this galaxy (NASA/STScI/Hubble Heritage Team). |

|

Figure 11.3. The Red Spider Nebula (NGC 6537) has waves of dust and gas extending a hundred billion kilometers. First cataloged by William Herschel over two hundred years ago, the subtle patterns are due to shock waves caused as outflowing material runs into the interstellar medium, a gas more sparse than the best vacuum on Earth (NASA/ESA/STScl/G. Mellema). |

kilometers, or 6 trillion miles, or explaining that stellar winds in the Red Spider Nebula (NGC 6537) produce waves of dust and gas a hundred billion kilometers high (figure 11.3), while nearly incomprehensible, has afforded general audiences unprecedented understanding of the incredible energy and matter involved in star birth and death.34 Hubble images of gravitational lensing caused by large clusters of galaxies, majestic barred spirals whirling through space, and spectacular globular clusters have been indelibly etched into the public imagination. But beyond this popular appeal, the Hubble Space Telescope has generated enough unique data to qualify as the most successful scientific experiment in history.