Astronomy’s Human Genome Project

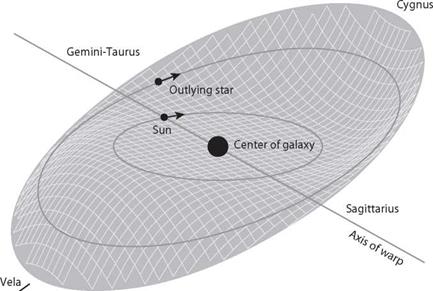

Michael Perryman has dubbed the Hipparcos mission astronomy’s equivalent of the Human Genome Project.22 Perryman explains that as astronomers more accurately map the location, velocity, and vector of stars in our galaxy we can understand the age and morphology of the Milky Way, how our galaxy has evolved in the past, and what the future holds for our Solar System and the galaxy. For instance, the Hipparcos mission has contributed to our better understanding of the galaxy’s current structure. We know our galaxy is not a perfect spiral, but is instead a barred spiral that’s warped so that the limbs at one end curve up and at the other bend down (figure 8.3). Another major contribution of Hip – parcos, for astronomers and popular audiences, is that the mission improved the estimates of distances to stars harboring exoplanets. In this way, it has crystallized our sense of the growing number of distant worlds in space. We’ve seen in the earlier chapters on the Solar System that planets and moons are potential abodes for life. As the Human Genome is a project to map the underlying structure of terrestrial life, so Hipparcos is a tool to help astronomers map plausible sites for extraterrestrial life. The search for life beyond the Earth is a foundational scientific pursuit, and it has attracted attention from some unlikely quarters.

The Vatican has maintained an observatory over the centuries in order to officially determine dates of the calendar year; the Gregorian calendar has been used in the Western world since 1582. However, astronomers of the Vatican Observatory more recently

|

Direction of Magellanic Clouds Figure 8.3. Hipparcos measured the positions for hundreds of thousands of stars and so was able to map out the disk of the Milky Way over 500 light-years. This was enough to detect a subtle warp in the disk, exaggerated in this schematic view. The shape of the disk is like a brimmed hat with the brim turned down on one side (ESA/Hipparcos). |

have been focusing on other concerns. In November 2009, Pope Benedict XVI called leading astronomers, astrobiologists, and cos – mologists to Vatican City to spend a week presenting recent findings regarding exoplanets orbiting nearby stars and to discuss the possibilities of intelligent life in those star systems.

Of the Vatican’s interest in exobiology, science reporter Marc Kaufman noted: “Just as the Copernican revolution forced us to understand that Earth is not the center of the universe, the logic of astrobiologists points in a similarly unsettling direction: to the likelihood that we are not alone, and perhaps that we are not even the most advanced creatures in the universe. This. . . may conflict with the stories we tell about who and what we are.”23 During the five-day meeting scientists addressed subjects such as the origins of life, extremophiles and their habitats, the likelihood of such life thriving on moons in the outer solar system, and whether life’s biosignatures could be detected on exoplanets.

As yet, exoplanets are mostly gas giants with little chance of life on them, but as the detection limit has reached Earth mass with NASA’s Kepler satellite, research spurs scientists, philosophers, and theologians alike to contemplate the implications for our place in the universe. “The questions of life’s origins and of whether life exists elsewhere in the universe. . . deserve serious consideration,” explained Jose Gabriel Funes, a Jesuit priest who is also the director of the Vatican Observatory. Co-author Chris Impey, who presented a paper at the meeting and co-edited the written pro – ceedings,24 comments: “Both science and religion posit life as a special outcome of a vast and mostly inhospitable universe. There is a rich middle ground for dialog between the practitioners of as – trobiology and those who seek to understand the meaning of our existence in a biological universe.”25 Reporter David Ariel, who also covered the meeting, aptly noted, “The Church of Rome’s views have shifted radically since Italian philosopher Giordano Bruno was burned at the stake as a heretic in 1600 for speculating, among other ideas, that other worlds could be inhabited.”26

For the moment, most of the vast inventory of stars remains out of reach. But several hundred relatively nearby stars are known to have planets, and Hipparcos has been an essential tool in measuring their distances. These new and potentially habitable worlds range from a dozen to a few hundred light-years away. Spanning the entire galaxy, one estimate is of 8 billion terrestrial habitable worlds around Sun-l ike stars, each of which has the potential to host life.27 This number is the same order of magnitude of the number of base pairs derived from the Human Genome Project, making literal the analogy of a vast mapping project to parse life in the Milky Way.