Big Surprises from Tiny Enceladus

Before Cassini arrived at Saturn, astronomers had paid little attention to Enceladus, a moon one-tenth the size of Titan. The Voyagers had shown in the 1970s that Enceladus was like an icy billiard ball, reflecting almost 100 percent of the Sun’s light. Its surface gave indications of activity since some parts were old and heavily cratered while others seemed to have been altered by volcanism in the last hundred million years. But nothing in earlier data prepared scientists for what Cassini would reveal.

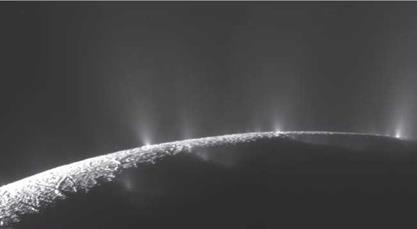

In 2005, plumes were seen rising from the fractured, icy surface (figure 5.5). It took several years and numerous observations by Cassini’s instruments to build up a picture of what was going on, but this is what we know. Enceladus emits geysers of tiny ice particles from a number of hot spots on its surface, near the southern polar region. The plumes are ejected at over 1,000 mph, greater than the escape velocity. They rise thousands of miles above the surface and form Saturn’s E ring.42 The geysers arise from geological features called “tiger stripes” that are 100-200°F warmer than

|

Figure 5.5. Saturn’s tiny moon Enceladus has all the ingredients for life: liquid water, energy, and organic material. Evidence for subsurface water came in the form of plumes visible above the moon’s sunlit edge. The plumes are composed of tiny ice crystals, ejected at hot spots on the surface from a salty underground ocean (NASA/JPL/SSI). |

other areas of the moon. Geologists think there’s spreading and tectonic activity in the tiger stripes, similar to what happens near deep-sea ocean ridges on Earth. Tidal heating must play a role, but the cause of the active geology on Enceladus is still a mystery, since the neighboring and similarly sized moon Mimas is inactive. Cassini has swooped through the plumes on several occasions, three times approaching the moon within 30 miles, “tasting” the material with its instruments to determine the chemical composition. The plumes are made of tiny ice particles and vapor that includes methane, ethane, propane, acetylene, and other organic molecules. The chemical composition may be like a comet. Most excitingly, the plumes contain sodium chloride—common salt. That’s the best indication so far that Enceladus has a subsurface ocean that occasionally erupts through the surface.

Much of this information was gathered in a series of swooping flybys, the closest of which zoomed within 15 miles of the surface. The imaging team calls these maneuvers “skeet shoots.” The spacecraft is moving so fast and is so close to the moon that the camera can’t track or lock onto any particular geological feature. Some images resolve features as small as 10 meters across, about the size of a living room. In late November 2009, Cassini made its eighth flyby of the tiny moon, the last before Enceladus entered the shadows of the long, cold Saturnian winter. With no new mission slated to return to the outer Solar System for at least fifteen years, it will be a while before we see images like this again. Meanwhile, the presence of liquids on Titan and inside Enceladus naturally leads to speculations about biology. Our dreams turn to the possibility of creatures floating in the dark and frigid depths of lunar seas far from their sheltering stars.