The Tireless Twins

Here are the basics of these twin long-distance explorers. The Voyagers are nearly identical spacecraft, each weighing about 800 kilograms, the same as a very small car. The heart of each spacecraft is a ten-sided polygon which contains the electronics and which shelters a spherical tank holding the hydrazine fuel. The polygon is fronted by a ten-foot diameter high-gain antenna, which has kept communicating with the home planet even as it receded to a tiny

|

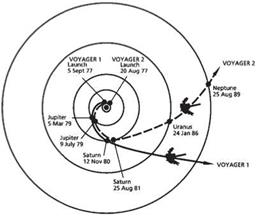

Figure 4.1. The twin Voyagers used gravitational assist to exceed the Sun’s escape velocity and leave the Solar System. Despite its later launch, Voyager 1 reached Jupiter four months ahead of Voyager 2 due to a more direct path. Both spacecraft rendezvoused with Saturn, but only Voyager 2 had an encounter with Uranus and Neptune (NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory). |

dot billions of miles away. Attached to one side of the polygon is a gold long-playing record; this apparent incongruity will be discussed later. Voyager’s ten scientific instruments are attached to a couple of booms that extend away from the central polygon. The instruments include cameras and spectrometers, and there are devices for measuring magnetic fields, charged particles, cosmic rays, and radio waves. The video camera is based on a design developed by RCA in the 1950s. That seems hopelessly archaic, yet the Voyager vidicons were very robust and they worked flawlessly.10 The mission cost $865 million through the Neptune encounter, and has been continuing on a dribble of funds as the spacecraft head beyond the Solar System. That works out to 5 cents per mile, cheaper than running a fuel-efficient car like a Toyota Prius. Actual fuel efficiency is even better. Each launch vehicle had 700 tons of fuel; so far the Voyagers are getting about 80,000 miles per gallon!

Solar power is inadequate in the outer Solar System; too little radiation would reach the spacecraft. Voyager used an onboard power system called a Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator, or RTG. Three of these were attached to a boom coming off the spacecraft. RTG’s had been used by the Vikings and the Pioneers previously, and subsequently they’ve been used by the Galileo, Ulysses, Cassini, and New Horizons spacecraft. Each RTG uses a fist-sized radiation source containing plutonium oxide to generate heat, which is continuously converted into electrical current.11 Plutonum-238 (which is distinct from the Plutonium-239 that’s used in nuclear weapons) decays with a half-life of eighty-eight years. The Voyagers were getting 470 Watts of power at launch, but now they’re down to 250 Watts. That gentle decline in power is an inevitable consequence of nuclear physics, and as power has diminished, instruments have been switched off. In a few years, the gyroscopes will be shut down, and in the mid-2020s the Voyagers will go silent.

These are remarkable little spacecraft. Even though they are long in the tooth and obsolete by modern standards, they continue to generate scientific discoveries after thirty-five years. Think of it—they communicate at 160 bits per second, or a lower information rate than spoken speech and 25,000 times slower than “basic broadband” Internet service; they do their work with less than three light bulbs’ worth of power; and they’ve barely used half of their 220 pounds of hydrazine fuel after traveling 10 billion miles! On the Earth, 8-track tape decks and LP records have been relegated to yard sales; at the edge of the Solar System they’re still cutting edge. Moreover, the Voyagers are not too old to learn “new media” tricks. They have 25,000 followers on Twitter between them, with Voyager 2 being the more garrulous of the pair.

Ed Stone is the “father” of these middle-aged twins. Stone has had a storied career, serving as director of the Jet Propulsion Lab and chair of the Division of Physics, Mathematics and Astronomy at Caltech. He’s a Fellow of the National Academy of Sciences and winner of the President’s National Medal of Science and NASA’s Distinguished Service Medal. He also has asteroid 5841 named after him. Stone has been principal investigator for nine NASA missions, but the Voyagers hold a special place in his affections. He started working on the project in 1972; he’s now seventy-six, and he has no intention of retiring or slowing down. He intends to follow their progress all the way into the depths of interstellar space. In a 2011 interview, he allowed himself some introspection: “What a journey, what a thrill. . . . We were finding things we never imagined, gaining a clearer understanding of the environment the Earth was a part of. I can close my eyes and still remember every part of it.”12