The Mission

Although the rovers subsequently got into some amazing scrapes, there was nothing “seat of the pants” about NASA’s planning for the mission. Each of the science instruments was exhaustively tested in the lab and in an environment designed to roughly mimic Mars.

Then, 150 potential landing sites were winnowed down to four and finally two. Site selection was an agonizing process, balancing science and safety, and taking into account any steep inclines and potentially hazardous rocks in the footprint of the landing area. To the scientists and engineers involved in the mission, the launch was a double-edged sword. On the one hand, after years of preparation and testing, nothing more could be done except watch the launch play out. On the other hand, $800 million of effort was on the line, and there were many opportunities for disaster. Everyone involved knew that over the previous thirty years, nearly half of the missions to Mars had been lost or had failed.

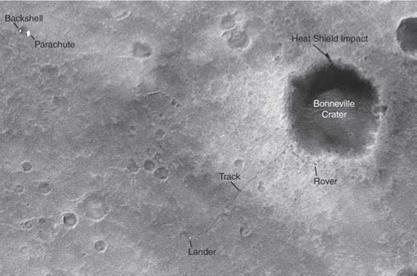

On January 4, 2003, after a journey of 300 million miles and seven months, Spirit entered the Martian atmosphere traveling at 12,000 mph, or twenty-five times the speed of sound. What followed was what team members called “six minutes of terror.” The spacecraft heated up and was buffeted by winds in the upper atmosphere. Five miles up, the parachute deployed on schedule and then rockets fired to further slow the descent. Cocooned by airbags on all sides, Spirit hit the surface and bounced four stories high in a lazy arc in the weak gravity. After bouncing a dozen or so more times and traveling a quarter of a mile, it came to rest (figure 3.2). The “bouncing bag” method had been used for Mars Pathfinder; it removes the need for a completely soft landing, but at the expense of unpredictable ricochets from the surface. In the control room at JPL in Pasadena, over two hundred scientists, engineers, and NASA managers exhaled. And then let out a raucous cheer.

Spirit landed in the Gusev crater, on a rolling surface of red soil and small rocks. Opportunity landed three weeks later on the far side of Mars in the middle of a flat plain called Meridiani Planum, bouncing into a crater just 70 feet in diameter. Scientists were elated and called it a “hole in one” since the crater rim seemed geologically interesting, but the result was pure luck since the spacecraft could not have been targeted that accurately. This was the first example of serendipity or circumstance playing a role in the mission. Spirit and Opportunity have identical hardware “DNA,” but their different environments began to play a role soon after landing. Both rovers went through a series of system checks before rolling gingerly off their platforms to begin exploration of the red planet.

|

Figure 3.2. The landing site, tracks, and location in September 1997 of the Spirit rover, as seen by the orbiting Mars Global Surveyor camera. Like its twin Opportunity, Spirit was designed to last for three months, yet it was active for over six years and drove nearly five miles before getting stuck in soft sand and being declared inactive by NASA in 2011 (NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory). |