The Privatization of Airmail

|

P |

elivery of mail was a feature of colonial America, although a haphazard and irregular practice, and was mainly a function of private enterprise. Mail was often left and picked up at taverns and inns. Benjamin Franklin served as Philadelphia’s postmaster beginning in 1737, and was appointed the deputy postmaster general for the American colonies in 1753. He brought order to the system by mapping routes between stations, establishing post roads and mileposts, and inaugurated the use of stagecoaches to deliver mail under contract. He was appointed postmaster general by the Continental Congress in 1775 and the practices he had put in place continued.

The Constitution of the United States specifically authorizes Congress to establish post offices and post roads. When California was admitted to the Union in 1850 and the discovery of gold (a main source of wealth for the United States at the time) made rapid communication essential between the seat of government and commercial centers in the east and the new, developing west coast, the government contracted with the privately owned “Pony Express” to deliver the mail. The Pony Express shortened mail delivery over the 2,000-mile route to about 10 days. Expedited communication has, from time immemorial, been a highly valued

quality of civilization and a legitimate, necessary governmental function.

Congressional legislation in the 19th century made railroads officially “post roads.” The Post Office Department contracted with the railroads to deliver intercity and transcontinental mail, which was the mainstay of national mail delivery until well into the 20th century. In the late 19th century, passenger trains included “postal cars,” where mail was sorted en route by postal employees.

The government “airmail” experiment that was begun in 1918 was a government operation because there was no reliable private sector to perform that mission. Contrary to the practice in other countries, passenger and cargo transportation has not been a government function in the United States. Even when the railroads were nationalized between 1917 and 1920 due to the requirements of transportation control in World War I, they were returned to private operation as soon as practicable. Although the government dalliance with airmail delivery was a successful experiment to advance a legitimate government function, it also hastened the building of an aviation infrastructure of lighted airways and landing fields that could inure to the benefit of a private aviation transportation system. As late as 1925,

|

|

however, it was hard to find much evidence of an emerging privately operated transportation system.

From the Wright’s first flight in 1903 to the middle of the 1920s, there had been only two known attempts to start a scheduled passenger flying service, or airline, in the United States. The first was the St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line inaugurated on January 1, 1914 to serve the

18- mile over water route between the two Florida cities with a 26-foot Benoist XIV flying boat. (See Figures 12-1 and 12-2.) Although the little air service carried 1,200 passengers over the twenty – three minute route during the next several months, at a fare of $5.00 each, business sagged with the departure of the northern tourists and their money in the spring, and the company folded.

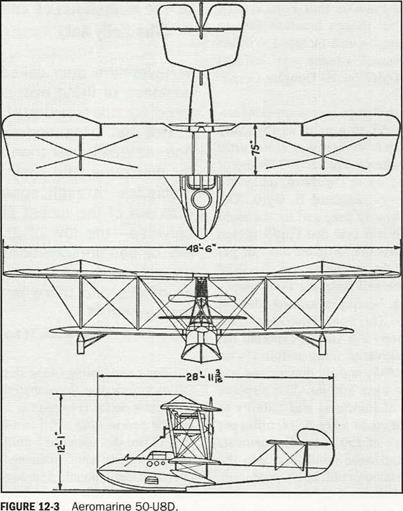

The other one was a short-lived idea of a Manhattan Cadillac dealer by the name of Inglis M. Uppercu. Uppercu ran an aerial sightseeing service in New York that he had started as an offshoot of having manufactured seaplanes (see Figure 12-3, Aeromarine Corp) for the Navy during World War I. In 1920, he bought out a small Key West to Havana mail line and began to supplement the cargo with passengers. Prohibition (which outlawed the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages) went into effect in the

United States beginning in 1920 as a result of the 18th Amendment, and Uppercu correctly figured that Cuba and the Bahamas, with their plentiful rum and sunshine, would make a fetching destination for thirsty and cold Americans.

He formed Aeromarine West Indies Airways and during his first year carried 6,814 passengers in seven flying boats, flying 95,000 miles. He noted that people who seemed to be terrified of flying at altitude over land appeared to have no fear of flying a few feet above water in a flying boat. The airline published schedules and met them. During its second year, the fleet was expanded to 15 aircraft, which carried 9,107 passengers on 2,000 flights. After two widely publicized accidents, resulting in the deaths of several passengers, and receiving exceedingly bad press that emphasized the complete absence of any kind of government mandated safeguards for the flying public, the bloom was off the rose. Uppercu shut down his airline in 1923.

Henry Ford, who by the middle of the 1920s was quite successful as the manufacturer of automobiles, saw that he had a legitimate business use for airplanes in the middle 1920s. Ford Motor Company had automobile plants in various locales, including Detroit, Cleveland,

|

Chicago, and Dearborn, and it was necessary to carry parts and machinery between them on a regular basis. Ford became acquainted with William E. Stout, an idea-man and former airplane designer, who had a passion to build an all-metal airplane. The craft would be built of duralumin, not quite as light as aluminum but twice as strong. Ford decided to back Stout who did, in fact, produce a single engine high wing monoplane constructed almost completely of metal, all as advertised. Its corrugated metal sides and thick wings looked remarkably like those produced in Germany by the Junkers Company,

but no one said anything. It was powered by the Liberty water-cooled engine, carried eight passengers and was dubbed Maiden Detroit.

Ford not only bought the plane, he bought the plant as well. He started Ford Air Transport and began a regular service between his plants. He then set Stout on a course to develop a bigger all metal airplane, one that would go down in history as the Ford Trimotor.

In 1924, Stout’s efforts resulted in the trimotor Ford 3-AT, a bulbous-nosed monstrosity configured with the pilot seated in an open cockpit above the high-winged fuselage. The

design was so horrendous that Ford retired Stout and turned the design function over to his team of engineers, which included William McDonnell. McDonnell’s name was destined to lead the merged McDonnell Douglas Corporation in 1967.

The story goes that progress on converting the mongrel 3-AT to a more aesthetically pleasing and efficient design was slow, until one day in 1926 when a Fokker F-7 Trimotor monoplane showed up in Dearborn, under the command of Admiral Richard E. Byrd. The airplane was gratuitously hangared for the night at Ford’s field, and it is said that Ford’s design team with tape measure in hand did not get much sleep that night. In due course, the Ford 4-AT Trimotor emerged from the Ford team’s plans and sketches, bearing a striking likeness to the Fokker F-7. The Ford Trimotor, affectionately dubbed the “Tin Goose,” sported the same heavy cantilevered wing without wire bracing as did the F-7, and its dimensions and engine mountings were similar. The airplane conveyed a sense of sturdiness and stability to the 14 passengers it could carry at 100 miles per hour over a distance of 250 miles. Refinements in this basic design were continued into the 1930s, with 199 Trimotors ultimately produced.

In spite of the individual efforts of a number of adventurers and various businessmen, in 1925 there was no momentum to be found in the world of commercial aviation. Progress was measured in fits and starts, like the two defunct airlines mentioned above, and popular confidence was justifiably lacking due to the unreliability of the engines and aircraft of the time. Passenger air traffic was basically unknown. We saw in Chapter 11 how things were about to change for the better in the quality and reliability of aircraft engines, and progress was also being made in airframe design and construction, yet aviation wandered aimlessly over the countryside. That is, except for the airmail. What the private sector needed was a reason to fly.