Airmail Story

|

I |

t was not long after the Wright brothers were first successful in marketing their airplane to the French and to the U. S. Army, in 1908 and 1909, that the idea occurred to someone in the Post Office Department that the airplane could be useful in delivering the mail—and faster than the railroads. Federal funding for airmail delivery was not forthcoming in spite of a bill introduced in Congress in 1910 by Congressman Morris Sheppard for that purpose. Beginning in 1911 without specific government funding, limited experimentation with airplanes hauling mail (15 pounds a load) was initiated. Congress was not convinced that the entire process of flying mail to a point over a United States Post Office, and dropping it from various heights to the ground, was not too hare-brained to be dignified by appropriations. Only in 1916 did Congress finally approve limited funding ($50,000 from the “Steamship Fund”) for the establishment of a trial airmail route, in large part because of the rapid improvement in the reliability of aircraft. In 1918, specific funding was finally approved (the Sheppard bill had been hung up in Congressional debate for eight years) with a $100,000 appropriation for the purchase, operation, and maintenance of airplanes for use by the Post Office Department.

A Rough Beginning

Operations began by using airplanes and pilots furnished by the Army Signal Corps. It soon was clear that the airmail experiment was, in reality, a training device and exercise for the Army, and that delivery of the mail often amounted to an afterthought. It also became clear that the lack of training and experience of Army pilots, particularly in cross-country flying and navigation, was going to be a problem. Otto Praeger was Second Assistant Postmaster General of the United States from 1915 to 1921. He believed that the carriage of mail by air would be a logical next step in mail service to the country, and he also believed that the carrying of mail would have the secondary benefit of proving the use of the airplane for commercial purposes. After World War I, it seemed that business interests in the United States could not figure out how to put the airplane to any beneficial or productive purpose. This was the age of barnstormers, daredevils, adventurers, and a sideshow mentality that overshadowed most other thinking on the subject of airplanes. Banner towing, the selling of rides, and the occasional charter hop from one municipality to another was about the extent of commercial benefit associated with aviation. Besides, flying was fraught with danger.

The aircraft available after World War I were numerous, but they were mostly JN-4s, the latest version of which was the H model. This airplane had an average speed of 50 miles per hour, 60 tops, and could carry some 150 pounds of mail. The route fixed as the first experimental airmail route was between New York and Washington, D. C., a distance of 218 miles, with an intermediate stop at Philadelphia, and the date set for its inauguration was May 15, 1918. Airplanes would depart both New York and Washington at the same time. In Washington, President Woodrow Wilson was in attendance, attesting to the magnitude and portent of the event, as was Otto Praeger and other Post Office dignitaries. (See Figure 10-1.)

The pilot selected for the Washington departure, Lt. George Boyle, was chosen more for his family contacts than for either his experience or his skill. (See Figure 10-2.) As the president watched, Lt. Boyle called “contact” and the propeller was pulled through for start, but nothing happened. After several attempts, amid an embarrassing silence from the august assembly, someone thought to check the airplane’s gas tank. It was empty. Upon being filled, the engine coughed to life and presently brand-new airmail pilot Boyle was finally airborne, and the airmail service had been launched, much to the relief of the Post Office and Army officials gathered there. (See Figure 10-3.) But there was yet another problem.

A pilot wishing to fly from Washington to Philadelphia is required to follow a generally northerly course, owing to the fact that Philadelphia is north of Washington. Lt. Boyle, however, turned to the south shortly after take off and landed in a pasture farther away from Philadelphia than where he started. The day was saved by the southbound mail, which arrived in Washington 3 hours and 20 minutes after it left New York. The second leg of the northbound route, from Philadelphia to New York, was salvaged when Boyle’s difficulties became known,

![]() whereupon the second-leg pilot loaded his airplane with Philadelphia mail and took off for New York.

whereupon the second-leg pilot loaded his airplane with Philadelphia mail and took off for New York.

|

|

|

FIGURE 10-1 President Woodrow Wilson at the inauguration of airmail—May 15, 1918. |

|

FIGURE 10-2 Major Reuben Fleet (on the left) briefs airmail pilot Lt. George Boyle before he begins his flight on May 15, 1918. |

|

Ш Scheduled Airmail Service

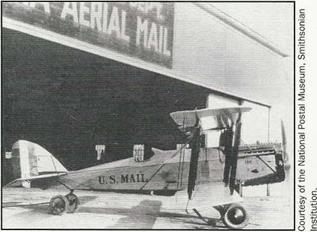

The experimental airmail service continued for about three months, until August 10, 1918, with an impressive record of 88% completion of flights attempted. The experiment using Army personnel had come to an end, and since it was the intention of the Post Office to use civilian pilots to operate the new, permanent airmail system, six new pilots were hired and new planes were put in service. (See Figure 10-4.) On August 12, 1918, the world’s first regularly scheduled airmail service was begun between New York

and Washington. On May 15, 1919, service was commenced between Cleveland and Chicago, the first segment of what was to ultimately become the transcontinental airmail route of the United States Post Office. Service on the segment from New York to Cleveland was deferred due to the adverse terrain, the Allegheny Mountains, which lay between those two cities.1 Attempts to inaugurate that service in December 1918 had failed due to the fact that every airplane sent aloft had been forced down by weather. But by July 1, 1919, that service had been begun as well. The

|

|

New York-Chicago route segment would come to be known as the “graveyard run,” and it would claim the lives of 18 airmail pilots.

The mail was mostly flown in Curtiss Jen – nys from the beginning of experimental service, but it was clear that more powerful and larger airplanes were needed. The Army had developed an appreciation for Glenn Martin’s airplanes during World War I, and was about to order the improved MB-2 bomber when the Post Office took over airmail delivery from the Army. In 1919, the Post Office applied some of the Congressional airmail appropriation to order six Martin MPs (mail planes), specially designed with nose cargo compartments capable of holding up to 1,500 pounds of mail, which were put into service in 1919 and 1920. Pilots crashed four of the new Post Office MPs on the New York to Chicago route, and the Post Office finally transferred the other two to the Army Signal Corps.

The Jennys gave way to the De Havilland DH-4 with Liberty engines, also leftovers from the war, that had earned the name “flying coffins” because of their propensity to catch fire on crashing, a not uncommon occurrence. (See Figures 10-5 and 10-6.) These planes generally had as

|

FIGURE 10-6 DH-4. |

instrumentation an airspeed indicator, an altimeter of sorts, and an oil compass. The planes had to be flown visually, by reference to horizon, sky, and land outside of the cockpit. Navigation was also by outside reference, referred to as “pilotage,” “contact flying,” or “ded reckoning.”2 Landmarks on the ground were the prime navigational reference for these early cross-country pilots, and when clouds or fog obscured these, finding one’s way became problematical, indeed. The airmail service did not operate at night; the mailbags were delivered to the trains for continuation of the journey until the next day, when once again the mail flew.

|

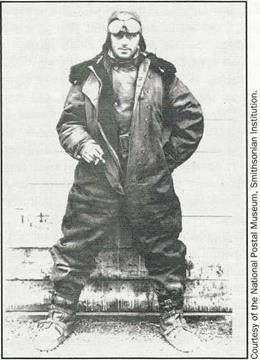

FIGURE 10-7 Wild Bill Hopson, airmail pilot. |

These two incapacities severely hampered the fledgling airmail service from fulfilling its promise.

• First, the lack of instrumentation to fly “blind,” or by instruments alone, was a problem that had to be addressed by the aircraft manufacturers, their vendors, and by the pilots themselves.

• Second, the lack of any land-based navigational infrastructure by which airplanes might find their way at night or in adverse weather conditions was a problem too big for individuals or the fledgling aircraft community.

A navigational infrastructure was an undertaking for government.

The first airmail pilots (see Figures 10-4 and 10-7), like Max Miller and Wesley Smith, began pushing the limits of “blind” flying, usually in order to extricate themselves from situations inadvertently encountered, like flying into clouds or fog. Smith is said to have taken a half empty bottle of whiskey aloft, which he placed on top of his instrument panel, to practice flying wings level with the whiskey level. Soon, he found that a curved tube filled with liquid and containing a ball, like a carpenter’s level, was available, and this he fastened to his instrument panel. And so it went. It was found that turns made at a constant, steady rate could be timed and the airplane could be rather accurately rolled out on predetermined headings. Sperry introduced a two-axis gyroscopic instrument that allowed a pilot to determine whether his airplane had inadvertently entered a turn. This was followed up with a three- axis instrument that showed changes in pitch attitude.