The Beginning of Naval Aviation

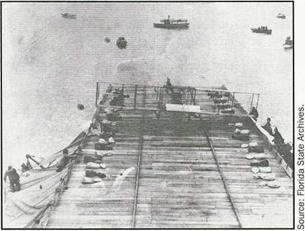

Curtiss remained busy. His sojourns in California during 1910 convinced him of the benefits of the winter climate there compared to the snow of Hammondsport and frozen Lake Keuka in New York. Late that year he leased North Island in San Diego Bay and offered free pilot training to both the Army and the Navy, receiving his first military students early the next year. In November 1910, a pilot employed by Curtiss, Eugene Ely, was the first to take off an airplane from a Navy vessel, the USS Birmingham, anchored at Hampton Roads, Virginia. (See Figure 8-8.) Two months later in January 1911, Ely became the first to land an airplane back aboard a vessel, the USS Pennsylvania anchored in San Francisco Bay, utilizing in both cases specially constructed wooden platforms on the ships, and in both cases without the benefit of any wind over the decks of the anchored ships. (See Figure 8-9.)

|

He set up shop facilities for conducting experimentation with floats in order to develop a successful seaplane, at that time called a

|

|

|

FIGURE 8-9 Eugene Ely making the first landing aboard a Naval vessel, January 1911. |

hydroplane. Although he had experimented with floats on the June Bug in 1908, and again in May and June 1910 with a canoe fitted centrally beneath one of his D2 machines, he had not been successful in getting an airplane off the water. At North Island, tests showed that significantly greater engine power was required to permit a takeoff from water as compared to land, so various hull designs were tested.

A breakthrough known as a “stepped” configuration essentially solved the problem of the water takeoff. The “stepped” hull design

incorporated a recessed aft section, so that the bottom of the aft section of the hull was higher than the forward portion of the hull. As speed increased, the aft section of the hull came out of the water first, which greatly reduced drag and produced a planing effect of the hull on water that later came to be known as “being on the step.” These original designs were modified and improved, spray patterns were controlled, and the improved hulls ultimately allowed take off from the water with close to the same horsepower as that required from land. By 1912, the Curtiss-designed aircraft hull had become state – of-the-art for the world. Further improvements were made as engines were mounted on the upper frame of the airplane, and as airframes were redesigned to account for pitch changes caused by these changes in the center of thrust. The Curtiss flying boats proved highly popular and sales were made to many foreign countries all over the world.6 (See Figure 8-10.)

|

In February 1911, he built his first tractor seaplane, with the engine and propeller at the front of the airplane (to avoid damaging water spray to the propeller) and the elevators at the rear. At the request of the Navy, he personally flew this craft out to the USS Pennsylvania anchored in San Diego harbor, where the airplane was winched aboard and then redeployed to the

water, completing the demonstration for what would become a common practice for the use of airplanes for scouting missions from warships. On May 8, 1911, the Navy ordered two Curtiss hydroplanes.