The Aerial Experiment Association

For the first time, the Aero Club of New York had been invited to attend, and in response to invitations from the exhibits committee, the leading lights of the aeronautical world, including Chanute, Langley, and Baldwin provided displays. Alexander Graham Bell, the inventor

|

of the telephone, was also there exhibiting his “tetrahedral kite,” a strange-looking contraption that he believed provided a means of lift. Although invited, the Wright brothers declined to attend, saying “It would interfere with our plans if we should make public at once a description of our machine and methods.”1

Bell visited the Curtiss exhibit (see Figure 8-2), and came away convinced that Curtiss was the greatest motor expert in the country. Curtiss was a practical, down-to-earth kind of man. Although intrigued by his experiences with Baldwin and others whom he had met in the aeronautical groups, he was not altogether convinced that winged flight was to be a practical reality. But Dr. Bell was practical, and he was a proven commodity—his reputation was fully established. Bell’s enthusiasm rubbed off on Curtiss, so a correspondence relationship between the two was established based on the idea that manned, controlled flight of an airplane was possible.

Curtiss wrote to the Wright brothers in May 1906, inquiring of their interest in his engines. The Wrights were not interested, but in September that year Curtiss was in Dayton at the behest of Baldwin in order to make repairs to a Curtiss engine being used on a

Baldwin dirigible. Baldwin, as a well-known aeronaut, knew the Wrights and introduced Curtiss to them. Curtiss was able to discuss with them their flying machine progress in some detail, and they showed him photographs of their machine in flight taken during the previous two years at Huffman Prairie. Although Curtiss remarked that it was the first time he had been able to believe that manned flight was possible, no one of any recognized credibility had ever actually seen the Wrights in the air. Although Baldwin would later say that Curtiss never had any thought at this time of taking up flying, it is reasonable to think that this visit with the Wrights might have combined with the Bell relationship to ignite that very interest.2

In October that year, Alberto Santos – Dumont made the first public airplane flight in the world in Paris. His 14-bis flew a distance of 200 feet at a height of 10 feet at 25 miles per hour. Spurred on by these developments and his own long-standing belief and commitment to flight, Bell bought one of the Curtiss engines and asked Curtiss to deliver it, in person, to Bell’s Nova Scotia home. He said he would pay Curtiss a consulting fee of $25 per day, plus expenses. He also invited Curtiss to join a small group of

men dedicated to finding a practical solution to the problems of flight. They agreed to meet at the Bell estate on Cape Breton Island in July 1907.

Bell had arranged to have the other members of his proposed investigative group at his house at the same time; there were Douglas McCurdy and Casey Baldwin, both recent graduates of the University of Toronto with master’s degrees in engineering, and Lt. Thomas Selfridge, whom we discovered in Chapter 7. Selfridge was a military expert in gliders and aeronautics and, like Curtiss, had some prior acquaintance with the Wright brothers. The group spent the next week at the Bell estate, becoming acquainted and discussing a wide range of issues relating to the scientific and engineering aspects of the problem of flight. General concepts of the operation and funding of the proposed undertaking were laid out by Dr. Bell. When he left at the end of the week, Curtiss came away favorably impressed with the great enthusiasm exhibited by the 60-year-old Bell, and with the way in which each man’s talent and experience complemented that of the others.

Details of the undertaking were worked out on a subsequent visit to the Bell house in September 1907. The group, known as the Aerial Experiment Association (AEA), was formally established on the next visit in October 1907, and although no profit was expected from their activities, it was agreed that all benefits and discoveries would be shared equally among the members. They began with gliding experiments using Bell’s strange tetrahedral design and then working with the proven Chanute designs of the biplane glider. They experimented with lift and control before moving on to any motorized attempt at flight.

The group moved operations from Nova Scotia to Hammondsport, where fabrication and machine working expertise was available at Curtiss’ shop. They were learning fast, and they had a lot to learn; yet they were making excellent progress. At the end of that year Curtiss wrote to the Wrights telling them of the work of the AEA and offering a gift to the Wrights of his latest 50-horsepower engine. He also alluded to the publication of the government’s recent request for proposals and specifications for the purchase of a flying machine, adding: “You, of course, are the only persons who could come anywhere near doing what is required.”3

On January 15, 1907, Thomas Selfridge wrote to the Wrights asking if they would share details of their glider construction and the results of their experiments with reference to the center of pressure “both on aerocurves and aeroplanes.” The Wrights responded three days later and referenced the requested information as being available in public addresses by Wilbur Wright and Chanute, both from 1903. They also referenced the information available in their patent. Everything that was disclosed by the Wrights to Selfridge was apparently already in the public domain.

By March of 1908 the AEA had its first powered machine. Called the Red Wing, it was a biplane with the Curtiss V8 40-horsepower engine, with a rudder mounted aft and an elevator forward, like the Wrights’ Flyer. Although Selfridge had been in charge of its design (each of the members took responsibility for one aircraft design), on the day of the inaugural flight he had been recalled by the Army to Washington, so it fell to Casey Baldwin to pilot the craft. Mounted on ice runners on the frozen surface of Lake Keuka near Hammondsport, the Red Wing lifted off and actually flew almost 100 feet before settling back on the ice. Its second flight five days later was its last, but it covered 318 feet, 11 inches, before crashing back onto frozen Lake Keuka due to lateral control problems. Contemporary reports described the flight as the first public heavier than air trip in America.

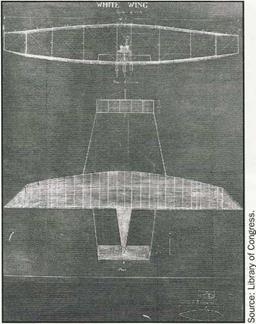

Casey Baldwin oversaw the next design, the White Wing (see Figure 8-3). It incorporated the salvaged engine from Red Wing and sported motorcycle wheels and tires, the first known aircraft to do so. An innovative steerable nose wheel was fashioned allowing a more controllable take off. After their learning experience with Red Wing, the group brain-stormed the problem

|

FIGURE 8-3 White Wing. |

of lateral control. They did not plan to incorporate “wing warping” since they were aware that this was the Wrights’ patented method of lateral stability and that, by law, a royalty would have to be paid for its use. Because of Professor Bell’s reputation and wide experience as an inventor, and because all of the flights of the AEA were open to the public, they took pains not to use any devices that might infringe the Wright patent. Bell came up with the idea of moveable panels located on the extreme ends of the wings which could be tilted up or down to either reduce or increase lift for that wing. He called these devices “ailerons,” or little wings.

Although unknown to the members of the AEA, the idea for ailerons had been first proposed some 40 years earlier by an English inventor, M. P.W. Boulton, who secured an English patent in 1868. Ailerons had also been experimented with in 1904 by the Frenchman, Robert Esnault-Pelterie, and again in 1906 by Santos – Dumont. Bell said that his idea for ailerons came from studying birds.

Beginning on May 18, 1908, White Wing made a series of seven flights before being destroyed in another crash. Baldwin, Selfridge, and Curtiss all flew the machine, with Curtiss setting a distance record of almost 1,000 feet on his first attempt. The AEA was making steady progress. Every flight was a new and important learning experience. Curtiss was next in line to design and supervise construction of a successor to White Wing.

About this time the weekly magazine Scientific American, in conjunction with the Aero Club of America, offered a beautiful silver trophy and a monetary prize to any aeronaut who could achieve certain prescribed flying goals in each of three successive years. The goal for the first year was that the airplane must fly in a straight course for a distance of one kilometer (3,281 feet). This was a feat already easily accomplished by the Wright Flyer (although few believed it), but the additional requirements set by the contest were that the flight be made in public and that the aircraft take off and land on wheels. The Wright Flyer did not have wheels. Besides, Wilbur had arrived in Paris on May 29, 1908 to begin a series of public flying displays planned for the European scientific community and the crowned heads of Europe. At the same time, Orville was putting the final touches on his plans for the public trials with the U. S. Army at Ft. Myer, scheduled for September. The Wrights were not interested in mere contests, and although they were especially invited by the Aero Club to make the first attempt, Orville declined.

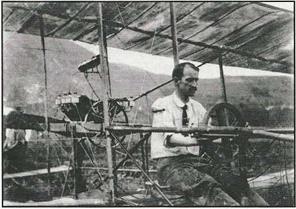

But Curtiss was interested, and he began modifying the White Wing design in order to produce an entrant for the Scientific American Cup. The new craft, dubbed by Dr. Bell the June Bug, incorporated the same 40-horsepower engine as the previous biplanes as well as the ailerons used in White Wing (see Figures 8-4 and 8-5). Its wings were painted yellow. Curtiss flew the June Bug successfully three times on June 21, 1908 and again on June 25, achieving sustained flight of 3,240 feet. The AEA was the first entrant to

|

FIGURE 8-5 Glenn Curtiss seated in the June Bug. |

|

|

contact the Aero Club and to request a trial for the Scientific American trophy (see Figure 8-6). A demonstration was scheduled for July 4, 1908 at Hammondsport.

The event was well attended by the July 4th crowd, most of whom had never seen an airplane, but thunderstorms prevented any flying until late in the afternoon. The assemblage lolled about for most of the day, sprouting umbrellas against the periodic thunderstorms. When the weather permitted, about 5 p. m., the June Bug was rolled out from under its tented enclosure and was made ready for flight. When the June Bug rose into the air, the astonishment of the crowd was evident, but the result was less than

satisfactory: a flight of only 2,200 feet. The problem was due to an incorrect attachment of the tail section to the fuselage. Once corrected, the June Bug again became airborne at 7 p. m. and flew over one mile in 1 minute and 42 seconds, successfully winning the trophy for the first time (of three required wins).

Everyone in the aviation community had glowing praise for Curtiss and the AEA for their magnificent achievement, with one exception. On July 20, 1908, Orville Wright sent a letter to Curtiss warning that use of the Wright’s control system was a violation of their patent and was not to be used for a commercial purpose or for exhibitions. Although the members of the AEA did not agree that their use of ailerons on the June Bug infringed the Wright patent, they all realized that the days of the AEA were numbered.

Two months later, on September 17th, Thomas Selfridge, one of the original four, was killed in the crash of the Wright Flyer (see pages 53-55) at Ft. Myer. On September 26, the day after Selfridges’ funeral, Dr. Bell convened the remaining members of the Aerial Experiment Association and in an address to the group summed up their extraordinary association together:

m We breathed an atmosphere of aviation from morning till night and almost from night to morning. Each felt the

stimulation of the discussion with the others, and each developed ideas of his own upon the subject of aviation, which were discussed by all. I may say for myself that this Association with these young men proved to be one of the happiest times of my life, w

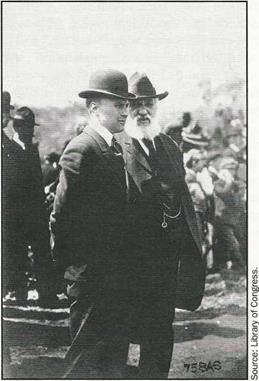

It was agreed that the AEA would continue but for six months more (see Figure 8-7). As the last project of the AEA, McCurdy oversaw the design and construction of the Silver Dart, an improved version of the June Bug, with a larger, liquid-cooled engine and a more efficient propeller. This craft was first flown in December, and on February 23, 1909, became the first flight of a controlled airplane in Canada at Baddeck Lake.

|

FIGURE 8-7 Lt. Thomas E. Selfridge and Dr. Alexander Graham Bell at Baldwin trials, August 18, 1908. |

In March, after the Silver Dart flew a circular course for over 22 miles, the AEA held its last meeting and closed its activities.

McCurdy and Baldwin would go on to form the Canadian Aerodrome Company with the goal of making airplanes for sale to the Canadian Army. Although they continued to fly the Silver Dart, and to construct several more airplanes of similar design, their efforts ultimately come to naught.

Curtiss, on the other hand, was just getting started. In March 1909, he produced a variant of the June Bug, called the Golden Flyer (also known as the Gold Bug), which he sold to the Aeronautic Society of New York for $5,000. This was the first commercial private sale in the United States. The Aeronautic Society, which began flying the craft at commercial exhibitions, agreed to pay the Wrights a royalty, but Curtiss refused.

Instead, he entered the Scientific American competition and, on July 17, 1909, was awarded the Scientific American trophy for the second time, flying a distance of 25 miles. On August 29, 1909, Curtiss won the speed competition (Gordon Bennett Cup) over a closed course at Rheims, France against stiff competition that included Louis Bleriot, who had made the first international flight on July 25, 1909 by flying the English Channel between Calais and Dover. Bleriot’s airplane, incidentally, also utilized ailerons for lateral control. Flying a stripped down version of the Golden Flyer, Curtiss set a world speed record of 43 mph at Rheims, barely edging out Bleriot.