■ Gliders

From the early to mid 19th century, to the Wright brothers’ success in 1903, controllable flight of “heavier than air” craft was a preoccupation throughout the civilized world among dreamers, engineers, and assorted tinkerers. The sketches and writings of Leonardo da Vinci in 1505 were the only known serious, theoretical treatment of the subject of flight until the publication in 1810 of a series of articles by the Englishman Sir George Cayley.

Today, Cayley is considered to be the founder of the science of aerodynamics because of his pioneering experiments with wing design and the effects of lift and drag, and his formulations concerning control surfaces and propellers. He concluded, by observing birds, that a curved surface (a wing) would support weight and, under the proper configuration of fuselage and other accoutrements, would permit flight. As a scientist, he kept meticulous records of his observations and the results of his experiments. In years to come, this documentation would greatly assist those who followed him in the quest for flight.

In 1804, Cayley built and flew a model of a glider that incorporated the principles of the cambered wing, and in 1808 he flew a full-scale version of this glider as a kite, thereby proving his basic wing theory. Cayley worked on his theories all his life. Between 1849 and 1853, he designed and built the first human-carrying gliders in history. His research probed the engineering essentials of aircraft design today, including the ratio of lift to wing area, the determination of the center of wing pressure, the importance of streamlining, the concept of structural strength, and the concepts of stability and control. Cayley’s work became the foundation of most of the future experimentation in flight.

Throughout the course of the 19th century, many pioneers contributed to the persistent quest of manned flight. Some got the cart before the horse, like the Englishmen John Stringfellow and his cohort William S. Henson. In their zeal they attempted to form a company called the “Aerial Steam Transit Company” in 1843, for the purpose of operating an international airline. The first problem the company had was the absence of any form of aerial conveyance, such as an airplane. There also was no form of propulsion to make the aerial conveyance go anywhere, although Stringfellow apparently worked at high pitch to develop a lightweight steam engine to be placed on the yet undesigned airplane. The attempt came to naught when the English House of Commons rejected the motion to form the company, with great laughter.

In apparent recognition of the unlikely commercial success of their venture, Henson married and moved to the United States, where no record has been located to support evidence of any further aeronautical involvements. But Stringfellow persisted and, in 1848, he was successful in developing a three-winged model aircraft on which he placed a lightweight steam engine that actually flew a distance of 120 feet. He is thus credited with producing the first engine-driven aircraft capable of free flight and, under the auspices of the Aeronautical Society, exhibited his machine at the world’s first exhibition of flying machines held in the Crystal Palace in London in 1868.

Others, such as the French sea captain Jean – Marie Le Bris, are noted more for their efforts than their successes. His legacy was a series of glider crashes occurring after short, unmanned flight. Francis Wenham was an Englishman who pursued the elusive reality of flight without success, but who did design and build the first wind tunnel. Wenham was a marine engineer, as was the Frenchman Alphonse Penaud, who brought to their interest in flight an engineering discipline that would enhance the ultimate success of achieving manned flight.

Penaud’s work was important to the Wright brothers’ success, by their own admission. Penaud is known for his experimentation with model aircraft, with results long studied by aeronautical engineers and historians. Penaud had shown that models are effective for purposes of experimentation. He demonstrated the usefulness of the twisted rubber band as a means of propulsion for model airplanes. These models were among the first powered, heavier than air objects ever to fly and went far to encourage experimenters that manned, powered flight was possible. Penaud’s “planaphore,” a model monoplane with tapered dihedral wings, an adjustable tail assembly, and a pusher-type propeller mounted on the tail of the airplane, flew as a demonstration in 1871 in Paris. The planaphore covered a distance of 131 feet and is acknowledged to be the first recorded flight of an inherently stable aircraft.

Efforts to find a workable means of propulsion, or thrust, for aircraft were the primary interests of two other engineers. Clement Ader, a French electrical engineer, and Hiram Maxim, chief engineer for an early electric utility, experimented with steam engines, at the time the only known reliable form of moveable power.

During the 1880s Ader built flying machines to which he attached 40-horsepower and 20-horsepower steam engines. The engines were effective in producing sufficient power to propel his clumsy and unwieldy machines, all of which were completely without any effective means of control, and by turns they all suffered the ignominy of the crash and burn.

In 1893, Hiram Maxim built an enormous biplane. It was 200 feet in length with a wingspan of 107 feet, and he mounted on it not one but two 180-horsepower steam engines. The platform for the engines, the boiler, and the three – man crew was 40 feet long and 8 feet wide. The machine was effectively affixed to the ground by attachments to a track over which it ran. It was made to move along the track at speeds of up to 42 miles per hour in a fashion described at the time by a journalist at the scene:

When full steam was up and the propellers spinning so fast that they seemed to become whirling disks, Maxim shouted, “Let go!” A rope was pulled and the machine shot forward like a railway train with the big propellers whirling, the steam hissing and the waste pipes puffing and gurgling, it flew over the 1800 feet of track in much less time that it takes to tell it.

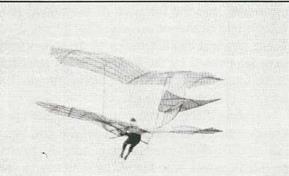

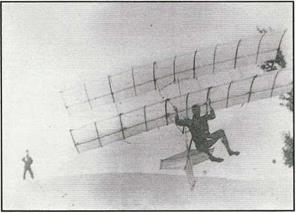

Otto Lilienthal (see Figures 5-3 and 5-4), a German engineer who believed that glider flight was a necessary prerequisite to powered flight, constructed and tested a series of monoplanes in the nature of what we today would call hang gliders. He made the most accurate and detailed observations about the properties of curved

|

|

|

FIGURE 5-4 Otto Lilienthal in flight—"to fly is everything.” |

surfaces, presenting for the first time observations concerning aspect ratio, wing shape, and profile, and conducted various experiments in his workshop that were built on the already proven idea of the cambered wing. In 1889 he published Birdflight as the Basis of Aviation, which contained the findings and conclusions from his experiments and which were presented in tabulated format. Beginning in 1894, he proved, through repeated successful glides of distances of over 1,000 feet, that manned flight was possible.

Between 1891 and 1896, Lilienthal made over 2,000 gliding flights, many over distances in excess of 1,000 feet, and for this period there are 137 known photographs of him in flight. He wrestled with the concept of control, using dexterous movements of his body to keep the glider in proper attitude, but was unable to develop an otherwise effective means of control. On August 9, 1896, the lack of control took its toll when his glider stalled at an altitude of 50 feet and plummeted to the ground, fatally injuring him. As he lay dying in the open field where he crashed, he was heard to have said, “Opfer mtissen gemacht werden.” Thus was started the tradition that has transcended the epoch of aviation, in the translation of his last words, “Sacrifices must be made.” Lilienthal’s exploits were publicly acknowledged, and photographs, interviews, and publication of his experiments and calculations were widely circulated. Percy Pilcher, a Scotsman and marine engineer and lecturer in naval architecture at Glasgow University, was intrigued by Lilienthal. He fashioned his own form of glider, but did not fly it until after he was permitted a visit to Lilienthal with the opportunity to practice in his proven machines. Pilcher died in his own gliding crash in 1899. He was later cited by Wilbur

Wright as having influenced the brothers’ experiments, who credited both Pilcher and Lilienthal in the success of the Wrights’ experiments.

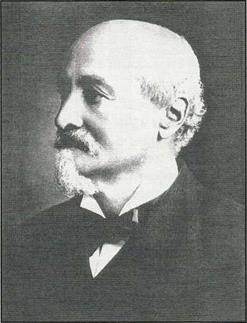

Octave Chanute was arguably the most important single influence on Orville and Wilbur Wright as they relentlessly pursued their goal of manned, powered flight. Chanute was an accomplished and successful civil engineer, president of the American Society of Civil Engineers, and

|

|

|

FIGURE 5-5 Octave Chanute. |

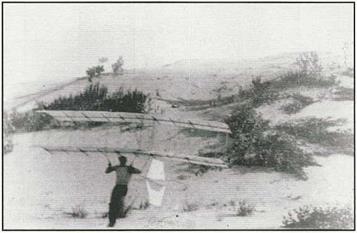

designer of the first railroad bridge over the Missouri River. (See Figure 5-5.) His interest in flight can be best understood as a hobby until he was in his sixties, when he published a book called Progress in Flying Machines, which compiled his extensive investigation of flight experimentation and research up to that time. (See Figures 5-6 and 5-7.) In 1896, Chanute began a series of experiments using gliders of his own design and construction. A short train ride from Chicago to the south lays the Indiana state line, along the shore of Lake Michigan. In June of that year, Chanute, his associate Augustus Herring, and two others established a campsite outside of Miller Junction, Indiana, among the famous dunes along Lake Michigan. Winds from the lake and the elevation of the dunes provided a very suitable venue for glider experimentation, and the isolation of the region provided some degree of privacy. (See Figure 5-8.) These physical characteristics of the topography were later noted by the Wrights in the selection of the Outer Banks of North Carolina for similar, although even more favorable, characteristics.

|

During this encampment, the Chanute party experimented with Lilienthal glider designs, making modifications that to them seemed appropriate. Progress was made, particularly in the six-winged version known as the “Katydid.” The party returned to the area in August 1896, and continued experiments with gliders, this time

|

FIGURE 5-7 Box-type glider (double-decker) design later used by the Wright brothers. |

concentrating on the double-deck kite version that would become the model for the Wright’s successful efforts a few years later. Chanute was encouraged by the results of the double-decker tests, and upon his return to Chicago he published the results in an article entitled “Recent Experiments in Gliding Flight.” The next year he followed this up with an article in the Journal of the Western Society of Engineers, wherein he recounted not only the 1896 experiments but also additional flights conducted by Augustus Herring in 1897. This free distribution of information was typical of the generous Chanute, who was genuinely committed to the advancement of manned flight regardless of any issue of credit for it.

The Wright brothers became seriously interested in the subject of manned flight in 1899. They wrote to Secretary Langley at the Smithsonian Institution, who was also in the process of experimenting with the idea of manned flight, and in that way became aware of the efforts of Chanute. Wilbur Wright first corresponded with Octave Chanute in 1900, and expressed particular interest in the structural engineering concept of strut and wire bracing that Chanute first introduced to aircraft design with the double decker. From this developed a lengthy and prolific correspondence and association between Chanute and the Wright brothers that extended for a decade, until his death in 1910. Chanute became a friend and confidant to the Wrights, and even accompanied them to the Outer Banks on several occasions. As a man of some stature as compared to the unknown Wright brothers, he defended them and vouched for their accomplishments during the secretive five-year period following their first successful controlled and powered flight in 1903, when, as we shall see, no one else would.

«All agreed that the sensation of coasting on the air was delightful, w

Octave Chanute, regarding first glider flights, 1894

|