Dirigibles

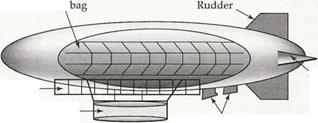

The second entry into the lighter than air category was the craft known as the dirigible. The marked distinctions between a balloon and a dirigible are the elongated shape of the dirigible; the control planes to allow pilots of the dirigible to turn, descend, and climb; and the presence of engines to provide thrust.

Both balloons and dirigibles used hydrogen gas to provide a lifting substance until the gas helium was extracted from natural gas in 1917. Since the United States had a monopoly on helium, no other country was privileged to use it in their airships. Instead, they were required to continue to rely on the very flammable hydrogen gas.

The first dirigibles (the term used here interchangeably with the term “airship”) flew in France between 1851 and 1884. The word dirigible is derived from the French diriger, meaning to steer. Airship, on the other hand, is a literal translation of the German, Luftschiff (airship).

Airships are of two main types, rigid and non-rigid. (See Figure 5-2.) The rigid airship was highly developed after the turn of the 20th century by Ferdinand Adolf von Zeppelin, a former German cavalry officer, who became acquainted with balloons during a visit to the United States. His LZ-1 became the first rigid airship to fly in a

17- minute sojourn over Lake Constance in 1900. This craft was 420 feet in length, supported by hydrogen gas, and cruised at 20 miles per hour with two 16 horsepower engines. Count von Zeppelin became a national hero because of his development of the very imposing and exciting “Zeppelins,” which could be seen overhead proceeding majestically through the German countryside. In 1909, Count Zeppelin formed the first passenger line for the carriage of passengers by air, Deutsche Luftshiffahrts A. G. (DELAG). DELAG, the airship company, carried passengers all over the country of Germany after its inauguration, and by 1913 had conducted over 1,600 flights, carrying 35,000 passengers without mishap.

With the advent of World War I, Germany and England geared up to produce airships by the hundreds. The British navy produced 200 airships between 1915 and 1918, more than Germany, and almost all of them were used for antisubmarine patrol. Germany produced 125 Zeppelins between 1914 and 1918, and employed them in offensive engagements over the English countryside, dropping bombs and otherwise wreaking havoc among the terrified population. The Zeppelins proved quite vulnerable to antiaircraft battery fire and to fighter aircraft. Of the 125 Zeppelins manufactured and placed in service during the war, only 6 survived.

|

Non-rigid airship (blimp)

Semirigid airship

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Several countries produced airships after the war. Both England and France built dirigibles, but accidents and mysterious disappearances caused the French to cancel their program in 1923. England continued operating dirigibles until 1930. Aerodynamic improvements were made as the technology advanced. The English R-34, completed in December 1918, had a total air resistance of only 7 percent of a hypothetical flat disc of the same diameter. The United States built its own dirigibles and even received a Zeppelin as a war prize from Germany after the cessation of hostilities in 1918. The 660-foot ZR-III was the 126th Zeppelin constructed by Germany

and was later renamed Los Angeles and placed in service by the U. S. Navy.

After the war, the Zeppelin continued to be used in passenger service between America and Germany, as well as between Germany and South America. Zeppelin flights continued until the occurrence of the Hindenburg disaster in Lakehurst, New Jersey, in 1937. The Hindenburg was undoubtedly the greatest airship ever constructed, boasting restaurants, staterooms, lounges, and other amenities for the enjoyment of its transatlantic passengers.

The Goodyear Company built airships for the United States, including the Akron in 1931,

commissioned for service in the U. S. Navy, and the Macon in 1933, also a navy craft. Both the Akron and the Macon were lost to weather, the last of a long line of airships that had come to similar grief. It was believed that the rigid airframe employed in the dirigibles was not sufficiently flexible, given its rather large dimensions, to withstand the vicissitudes of rough air and storms. The days of the rigid airship thus came to an ignominious close with their last production in the 1930s.

The non-rigid airship, or blimp, was placed in service by the United States Navy in World War II in convoy operations, and proved effective as an anti-submarine weapon. The only service to employ blimps in World War II, the United States Navy, worked 170 of the nonrigid airships over the Atlantic during the war, escorting 89,000 ships and logging some 500,000 hours flying time.

Today, blimps are used almost exclusively as promotional devices, employing television cameras for golf event coverage or other sporting events, or displaying brand names of commercial products on their ample sides. The advent of international terrorism after September 11, 2001, however, has caused renewed interest in the subject of blimps as a potential countermeasure against terrorist attacks in the United States.