Beginnings

|

T |

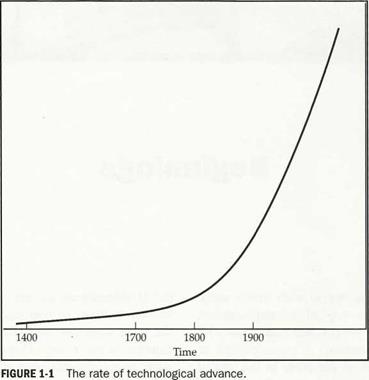

his is a story that begins with man’s earliest reported technological accomplishment, the invention of the wheel, and continues with an ever-increasing intensity. A curve plotted on one axis as time and on the other as the rate of technological advance will depict a flat to gradually rising line, becoming at a point a rapidly rising line, disclosing a recent very high rate of technological accomplishment. (See Figure 1-1.) Between 1790 and 1870, for example, there were just over 40,000 patents granted in the United States for that entire 80-year period. During the 30 years between 1870 and 1900, the Patent Office granted over 400,000 patents, a 10-fold increase in slightly more than one third of the time. In 1870, there was nothing in America that could be called a steel industry; but by 1900, over 10 million tons of steel were being produced annually, more than the rest of the world combined. As men struggled to fly, the rate of technological innovation was beginning to move up, but it had been a long time coming.

All modern-day accomplishments are based, to one degree or another, on the efforts and accomplishments of those who went before. The ancient Phoenicians sailed the confines of the Mediterranean Sea by reference to land, and also by reference to the sun and stars. The length of

the Mediterranean, its east and west limits, were known to them as Asu (east) and Ereb (west), the word roots that form the names of Asia and Europe in use today. Ocean travel was coastwise. Improvements were made to the shapes of sails and hulls used in early maritime commerce. Insurance and accounting came into vogue in the maritime trading centers around the Mediterranean, in the city-states such as Venice. Gunpowder arrived by the 9th century and, by the late 12th century, the magnetic compass was coming into common use on land and sea.

But the rising curve of progress really only begins with the rise of Western Civilization and the Rule of Law. Circumstances conducive to invention and innovation depend on many factors, including incentive to innovate—like the profit motive—and protection for the results of invention, like patent law. These and other relevant factors depend on a stable, progressive, and lawful society, and a strong government. Magna Carta (The Great Charter), in 1215, establishing for the first time limitations on the arbitrary powers of the King of England, is widely regarded as the cornerstone of personal liberty. Its principles have evolved into broad constitutional concepts embraced today. In 1420 began a period of progress and enlightenment known as the Renaissance

|

(rebirth), a time of advances in astronomy, anatomy, engineering, physics, and art. Great leaps of mind made by the luminaries of that day included the idea that man might actually fly—or so believed Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519). His sketches depicting wings to support manned flight disclose that he understood the same basic airfoil concept used today. His ideas on the subject were lost for a period of 300 years before rediscovery.

«When once you have tasted flight, you will forever walk the earth with your eyes turned skyward, for there you have been, and there you will always long to return, w