Eugen Sanger

Born in 1905, he was of the generation that came of age as ideas of space flight were beginning to germinate. Sanger’s own thoughts began to take shape while he was still in grammar school. His physics teacher gave him, as a Christmas present, a copy of a science-fiction novel, AufZwei Planeten (“On Two Planets”). “I was about 16 years old,” Sanger later recalled. “Naturally I read this novel avidly, and thereafter dreamed of doing something like this in my own lifetime.” He soon broadened his readings with the classic work of Hermann Oberth. “I had to pass my examination in mechanics,” he continued, “and had, therefore, made a particular study of this and related subjects. Then I also started to check and recalculate in detail everything in Oberth’s book, and I became convinced that here was something that one could take seriously.”

He then attended the Technische Hochschule in Vienna, where he tried to win a doctoral degree in 1928 by submitting a dissertation on the subject of rocket – powered aircraft. He did not get very far, later recalling that his professor told him, “If you try, today, to take your doctor degree in spaceflight, you will most probably be an old man with a long beard before you have succeeded in obtaining it.” He turned his attention to a more conventional topic, the structural design of wings for aircraft, and won his degree a year later. But his initial attempt at a dissertation had introduced him to the line of study that he pursued during the next decade and then during the war.

In 1933 he turned this dissertation into a book, Raketenflugtechnik. It was the first text in this new field. He wrote of a rocket plane burning liquid oxygen and petrol, which was to reach Mach 10 along with altitudes of 60 to 70 miles. This concept was significant at the time, for the turbojet engine had not yet been invented, and futurists, such as Aldous Huxley who wrote Brave New World, envisioned rockets as the key to high-speed flight in centuries to come.21

Sanger’s altitudes became those of the X-15, a generation later. The speed of his concept was markedly higher. He included a three-view drawing. Its wings were substantially larger than those of eventual high-performance aircraft, although these wings gave his plane plenty of lift at low speed, during takeoff and landing. Its tail surfaces also were far smaller than those of the X-15, for he did not know about the

![]()

|

stability problems that loomed in supersonic flight. Still, he clearly had a concept that he could modify through further study.

In 1934, writing in the magazine Flug (“Flight”), he used an exhaust velocity of 3,700 meters per second and gave a velocity at a cutoff of Mach 13- His Silbervogel, Silver Bird, now was a boost-glide vehicle, entering a steady glide at Mach 3.5 and covering 5,000 kilometers downrange while descending from 60 to 40 kilometers in altitude.

He stayed on at the Hochschule and conducted rocket research. Then in 1935, amid the Depression, he lost his job. He was in debt to the tune of DM 2,000, which he had incurred for the purpose of publishing his book, but he remained defiant as he wrote, “Nevertheless, my silver birds will fly!” Fortunately for him, at that time Hitlers Luftwaffe was taking shape, and was beginning to support a research establishment. Sanger joined the DVL, the German Experimental Institute for Aeronautics, where he worked as technical director of rocket research. He did not go to Peenemunde and did not deal with the V-2, which was in the hands of the Wehrmacht, not the Luftwaffe. But once again he was employed, and he soon was out of debt.

He also began collaborating with the mathematician Irene Bredt, whom he later married. His Silbervogel remained on his mind as he conducted performance studies with help from Bredt, hoping that this rocket plane might evolve into an Amerika – Bomber. He was aware that when transitioning from an initial ballistic trajectory into a glide, the craft was to re-enter the atmosphere at a shallow angle. He then wondered what would happen if the angle was too steep.

He and Bredt found that rather than enter a glide, the vehicle might develop so much lift that it would fly back to space on a new ballistic arc, as if bouncing off the atmosphere. Stones skipping over water typically make several such skips, and Sanger found that his winged craft would do this as well. With a peak speed of 3-73 miles per second, compared with 4.9 miles per second as the Earth’s orbital velocity, it could fly halfway around the world and land in Japan, Germany’s wartime ally. At 4.4 miles per second, the craft could fly completely around the world and land in Germany.”

Sanger wrote up their findings in a document of several hundred pages, with the title (in English) of “On a Rocket Propulsion for Long Distance Bombers.” In December 1941 he submitted it for publication—and won a flat rejection the following March. This launched him into a long struggle with the Nazi bureaucracy, as he sought to get his thoughts into print.

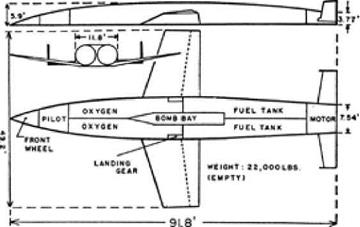

His rocket craft continued to show a clear resemblance to his Silbervogel of the previous decade, for he kept the basic twin-tailed layout even as he widened the fuselage and reduced the size of the wings. Its bottom was flat to produce more lift, and his colleagues called it the Platteisen, the Flatiron. But its design proved to be patentable, and in June 1942 he received a piece of bright news as the government awarded him a Reichspatent concerning “Gliding Bodies for Flight Velocities Above Mach 5.” As he continued to seek publication, he won support from an influential professor, Walter Georgii. He cut the length of his manuscript in half Finally, in September 1944 he learned that his document would be published as a Secret Command Report.

The print run came to fewer than a hundred copies, but they went to the people who counted. These included the atomic-energy specialist Werner Heisenberg, the planebuilder Willy Messerschmitt, the chief designer Kurt Tank at Focke-Wulf, Ernst Heinkel of Heinkel Aircraft, Ludwig Prandtl who still was active, as well as Wernher von Braun and his boss, General Dornberger. Some copies reached the Allies after the Nazi surrender, with three of them being taken to Moscow. There their content drew attention from the dictator Josef Stalin, who ordered a full translation. He subsequently decided that Sanger and Bredt were to be kidnapped and brought to Moscow.

At that time they were in Paris, working as consultants for the French air force. Stalin sent two agents after them, accompanied by his own son. They nevertheless remained safe; the Soviets never found them. French intelligence agents learned about the plot and protected them, and in any case, the Soviets may not have been looking very hard. One of them, Grigory Tokaty-Tokayev, was the chief rocket scientist in the Soviet air force. He defected to England, where he wrote his memoirs for the Daily Express and then added a book, Stalin Means War.

Sanger, for his part, remained actively involved with his rocket airplane. He succeeded in publishing some of the material from his initial report that he had had to delete. He also won professional recognition, being chosen in 1951 as the first president of the new International Astronautical Federation. He died in 1964, not yet 60. But by then the X-15 was flying, while showing more than a casual resemblance to his Silbervogel of 30 years earlier. His Silver Bird indeed had flown, even though the X-15 grew out of ongoing American work with rocket-powered aircraft and did not reflect his influence. Still, in January of that year—mere weeks before he died—the trade journal Astronautics & Aeronautics published a set of articles that presented new concepts for flight to orbit. These showed that the winged-rocket approach was alive and well.23

What did he contribute? He was not the first to write of rocket airplanes; that palm probably belongs to his fellow Austrian Max Valier, who in 1927 discussed how a trimotor monoplane of the day, the Junkers G-23, might evolve into a rocket ship. This was to happen by successively replacing the piston motors with rocket engines and reducing the wing area.24 In addition, World War II saw several military rocket-plane programs, all of which were piloted. These included Germany’s Me – 163 and Natter antiaircraft weapons as well as Japan’s Ohka suicide weapon, the

Cherry Blossom, which Americans called Baka, “Fool.” The rocket-powered Bell X-l, with which Chuck Yeager first broke the sound barrier, also was under development well before war’s end.25

Nor did Sanger’s 1944 concept hold military value. It was to be boosted by a supersonic rocket sled, which would have been both difficult to build and vulnerable to attack. Even then, and with help from its skipping entry, it would have been a single-stage craft attaining near-orbital velocity. No one then, 60 years ago, knew how to build such a thing. Its rocket engine lay well beyond the state of the art. Sanger projected a mass-ratio, or ratio of fueled to empty weight, of 10—with the empty weight including that of the wings, crew compartment, landing gear, and bomb load. Structural specialists did not like that. They also did not like the severe loads that skipping entry would impose. And after all this Sturm und drang, the bomb load of 660 pounds would have been militarily useless.26

But Sanger gave a specific design concept for his rocket craft, presenting it in sufficient detail that other engineers could critique it. Most importantly, his skipping entry represented a new method by which wings might increase the effectiveness of a rocket engine. This contribution did not go away. The train of thought that led to the Air Force’s Dyna-Soar program, around I960, clearly reflected Sanger’s influence. In addition, during the 1980s the German firm of Messerschmitt-Boel – kow-Blohm conducted studies of a reusable wing craft that was to fly to orbit as a prospective replacement for America’s space shuttle. The name of this two-stage vehicle was Sanger.27