JIUQUAN

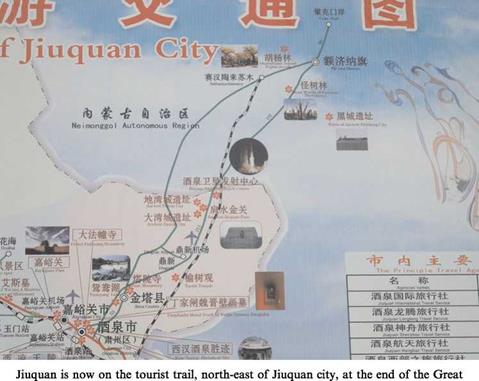

Jiuquan launch site is located in the Gobi Desert in north-west China. It is the home of the Long March 2 rocket. The launch site is 90 km north-east of the oasis city of Jiuquan, which marks the end of the forts of the Great Wall and is now a tourist destination. Jiuquan is a modern, well-equipped, prosperous city, laid out in a grid, softened by windbreaks and tree-planting campaigns, now featuring a luxury hotel.

Getting from Jiuquan city to the launch site is a 90-min train journey through desert featuring bushes and small trees. The environment is similar to Russia’s Baikonour launch site in Kazakhstan and, indeed, the long, winding trade route known as the Silk Road passes near both. Storms whip up the desert sands from time to time. Being desert, the average rainfall is very small – only 44 mm annually. A river runs through the site, though it normally dries out in the summer. This is a place of extremes. Temperatures range from -34°C in December to + 42.8°C in July. Averages are kinder: from -11 °С in January to +26.5°C in July. The winter nights are bitterly cold, down to -30°C, but the skies are brilliantly clear. It is cold to work in Jiuquan in mid-winter and personnel there receive a subsidy for their winter clothing. The thin soil is a light, dusty brown shale. There are few bushes there, only brown camelthom and a few wild animals, mainly yellow goats and wild deer. Later, some elms and red willows were planted. Not far from the launch site, Mongolian

|

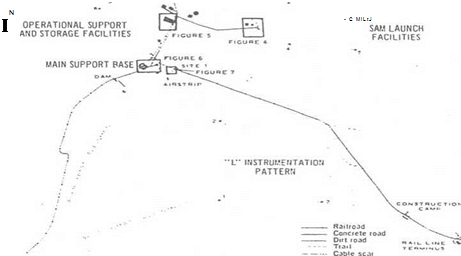

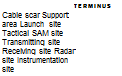

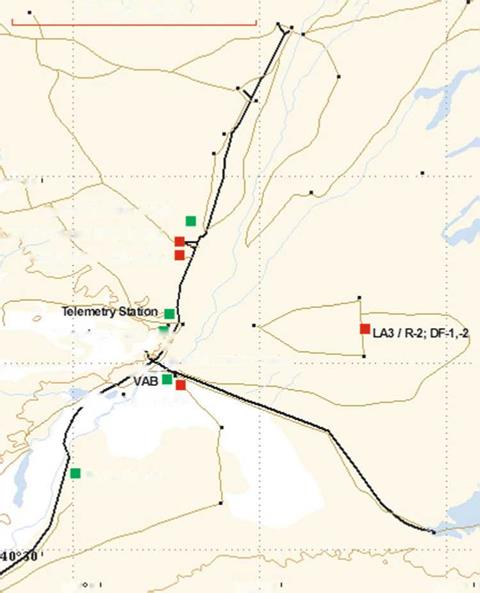

The original map of Jiuquan compiled by American intelligence. Then it was given the name of Shuang Cheng Tzu. Notice the protective surface-to-air missile sites.

herdsmen may be seen from time to time minding their sheep. Camels wander past periodically.

Like Baikonour, there are two parts to Jiuquan launch center: the cosmodrome and the town, about 20 min apart by car. The cosmodrome is a closed area covering 5,000 km2, bordered by a rim of desert mountains, visited by foreigners only when involved in particular missions. Like Baikonour, the facilities are quite spread out, connected by railways and roads. At one point, sand dunes encroach onto the railway; a detachment of soldiers is assigned nearby, their principal job being to clear the dunes when they drift onto the track. The town is laid out in a grid and is equipped with a railway station from Jiuquan city, coal-powered power plant, reservoir, stadium, hotel, and even a karaoke club. It is divided into four areas: military, commercial, residential, and technical. Staff at Jiuquan must, to a certain extent, learn to be self-reliant. Some of them keep pigs. The reservoir for the launch

![]()

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

NAUTICAL MILES

Expansion of Jiuquan, as recorded by American intelligence.

|

|

|

Optical Tracking Station

LA2A Pad 5020/ DF-3.-4; CZ-1 LA2B Pad 138 / FB-1; CZ-2

Technical Center ■/ v /

41°0′ /

41°0′ /

X LA4 / CZ-2F

Radar Station

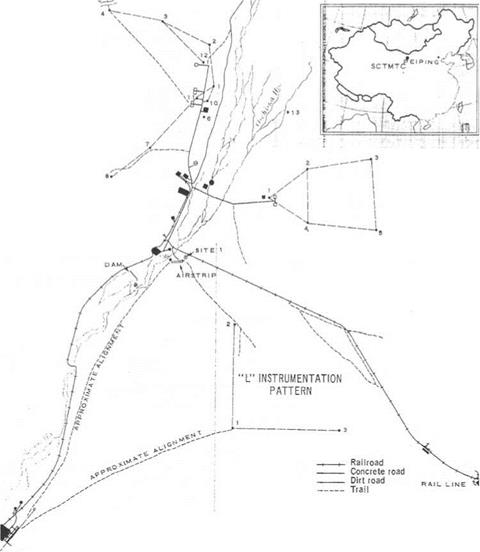

Map of Jiuquan now, with the new construction after 1992. Courtesy: Mark Wade.

|

Wall. |

site, which is replenished during the rainy season, is used for breeding fish. Air conditions there can be extraordinarily clear: one observer brought out his particle detector at the launch site and found that the level of particles was one in a million – the standard of clean room conditions! We have only limited accounts of Jiuquan in its early days and did not get significant details until Swedish satellite engineers visited in the 1990s [4].

The original base was formally delimited as a 2,800-km2 military area in 1962. The site dates to its days as a missile base in the early 1960s, with two subsequent waves of expansion, the first in the 1970s for the first Earth satellite and the second in the 1990s for the manned space program. The original part is called the north site and comprises two pads (one sub-divisible into a second), simple concrete constructions, 60 x 60 m, with an underground control bunker with a periscope. For launches, rockets are brought to the pad on a 55-m-tall, 1,400-tonne moveable service gantry running on 17-m-wide rails. The rocket is then brought to a massive 11-floor umbilical tower with supporting arms which provides fuel, gas, and electricity right up to the final moments of the countdown.

Adjacent to the pads are the Huxi Xincun range control center, assembly buildings, blockhouses, and electricity station. The main processing building is 140 m long; it has an area of 4,587 m2 with a 90 x 8-m assembly hall and a 24 x 8-m

|

Original building, Jiuquan. Its simplicity in the desert landscape is evident |

The original pad, Jiuquan, used from Dong Fang Hong onward.

fuelling hall. Equipment can be moved around by a crane able to lift 16 tonnes. Adjacent are 25 test rooms for checking out parts of a spacecraft. Beside them are a solid-rocket motor checkout and processing hall, 24 x 12 m, with crane, storage, and test facilities. The halls guarantee clean room standards of 100,000 class (one dust particle in 100,000 or less), temperatures of 20.5°C, and humidity in the 35-55% range.

|

Original pad close-up, Jiuquan. The second is in the background. |

Fuels are stored in underground bunkers. There are barracks for the militia who assist in the launchings and four-storey apartment blocks for workers involved in the maintenance of the site. Willow and white poplar trees are planted around the buildings and walkways to provide windbreaks and color. Launches from Jiuquan curve over to the south-east and visitors can watch launches from an observation site 4 km to the east of the pad, ringed by distant mountains. Sven Grahn, the first Western visitor to see a Chinese launch, recalled: “… tables and chairs were arranged directly on the sand and there were loudspeakers on telephone poles to relay the countdown in Chinese. Commands to personnel around the pad were given

|

і* |

|

Getting around at Jiuquan – by train. Courtesy: Sven Grahn. |

|

The new pads at Jiuquan. The vehicle assembly building is at the top, leading down to the main pad, with the second pad on a branch to the right. |

by whistles and flags.” The main forms of surface transportation were steam trains and military trucks.

The second substantial expansion in the 1990s saw construction of a vertical vehicle assembly building and a new steel launch tower. The south site comprises:

• technical center – Vehicle Processing Building, transit building, nonhazardous operations building, hazardous operations building, solid-rocket motor building;

• crawler and paved road to the pad;

• two new launch pads;

• umbilical tower;

• launch control center.

Traditionally, Chinese rockets were assembled on the ground in a horizontal position, towed to the pad by tractor, and then reassembled vertically on the pad by cranes. Now, with the Vehicle Processing Building, it is possible to do all the assembly vertically indoors and roll out a ready-to-go rocket to the pad, with fuelling the major task remaining before countdown. At the new pad, the turnaround period is three days, which means that a new rocket could be ready for a mission within 72 hr of the previous launching.

The Vehicle Processing Building is the equivalent of – and looks like – the famous Vehicle Assembly Building at Cape Canaveral and is constructed from reinforced concrete. It is 92 m high, 27 m wide, and 28 m long, with a 13-floor platform, cranes able to lift 17, 30, and 50 tonnes, with two high bays and two vertical processing halls, and is thereby able to prepare two launches at a time. Engineers can access a rocket from nine different levels. The door of the building is 74 m tall, 8 m wide at the top, and 14 m wide at the bottom, and weighs 350 tonnes, made up of six 20- tonne sections. The building dominates the surrounding desert landscape and can be seen 20 km away.

Adjacent are the horizontal transit building, 78 m long by 24 m, class 10,000 (not more than one particle of dust in 10,000 cm3) with air ducts to blow dust away, used to test out the launch vehicle, transit room, non-hazardous operations building for spacecraft checking in clean room conditions, and a hazardous operations building where fuels are loaded before launch. Shenzhou is held in a 12-m-tall scaffold before being lifted by a 15-tonne crane to the top of its rocket. The preparation hall has motivational gold slogans printed on a red background.

Linked by fiber optic cable 7 km from the Vehicle Processing Building is the 400 m2 launch control center, equipped with a main control room with four rows of work stations and two smaller control facilities, facing the launch pad 1,500 m distant. The normal criteria for launch are temperatures of-10°C to +40°C, winds of less than 10 m/sec, visibility of 20 km, and no lightning or thunder within 40 km.

To get to the pad 1,490 m distant, the assembled Long March 2F travels on a crawler 24 m long, 21 m wide, 8 m high, weighing 750 tonnes, and able to travel at 1.02 km/hr. Powered by eight electric motors and traveling at 20 cm/sec, it takes the crawler 40 min to travel from the Vehicle Processing Building to the launch pad. There, the launcher and spacecraft are grappled by the umbilical tower, an 11-floor fixed steel structure 75 m tall, with floors for fuelling, electrical connections, firefighting equipment, and an elevator. Underneath is an underground equipment room. There is a lightning conductor, flame trench, and a steel pipe down which astronauts may slide in 60 sec in an emergency evacuation to a protected bunker.

A second pad branches just off to the left. It was first used only weeks after the first manned mission when a Long March 2D put into orbit the FSW 3-1 recoverable satellite. The FSW was brought down to the pad by a new, 91-m-tall launch tower used to test, integrate, and fuel the assembled complex, equipped with no fewer than 40 testing workshops. When images of a second, close-by pad were spotted by satellite in the 1990s, observers realized that the Chinese could only have one capability in mind: to launch a space station first and then a manned spacecraft in quick succession thereafter.

Jiuquan has progressed from being a secret, off-map facility in the 1960s. Scientists were admitted in connection with satellite launchings in the 1990s and the media in the 2000s to follow the Shenzhou missions. Jiuquan city is on the tourist map, its main hotel has Shenzhou memorabilia, and the cosmodrome’s existence is at last acknowledged (photo).