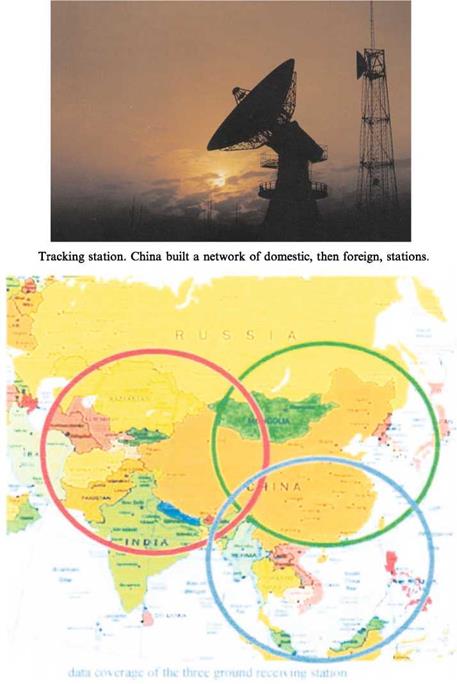

THE TRACKING INFRASTRUCTURE

The tracking infrastructure may be divided into domestic land stations, foreign land stations, and maritime stations. China first began space tracking soon after the Soviet Union launched Sputnik in 1957 and, in early 1965, Zhou Enlai made the first preparations for a ground tracking network for China’s own first satelhte. Two years later, construction began of seven ground stations at strategic points on the Chinese land mass, the main control center located in Weinan, Shaanxi, each station being equipped with tracking radars, signal receivers, optical trackers, data-processing systems, and control systems to send commands to the satellite. Later, more sophisticated and accurate laser trackers were introduced. The most westerly station was Kashi (also known as Kashgar) in the high western desert and this became designated the “number 1 tracking station” because it was the first station Chinese satellites would overfly on their west-to-east paths across the sky. For the communications satellites introduced in the 1980s, China built more ground stations: Nanjing (1975), Shijiazhuang (1976), Kunming (Sichuan) and later Urumqi (1982), Beijing (1983, the central station), and Llasa, Tibet (1984).

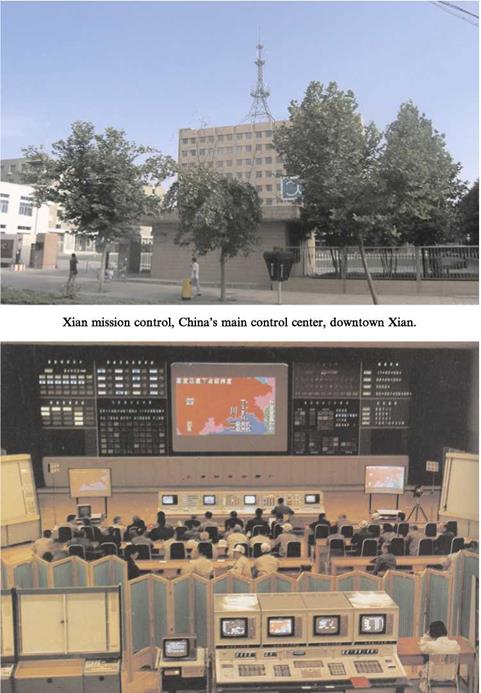

China’s main mission control is located in the city of Xian, famous for its underground army of terracotta soldiers, located at 34.3°N, 108.9°E. Dating to 1967, it was originally called the Satellite Survey Department and comprises a downtown mission control (photograph) and an out-of-town set of tracking arrays on a

|

|

|

Inside Xian mission control. |

plateau in the mountains, equipped with antenna farms, masts, and communications dishes. Chinese farmers may be seen gathering in wheat by hand on the terraces they share with the station. The downtown mission control room comprises television screens, consoles, plotters, and high-speed computers that follow, calculate, and predict the orbital paths of all Chinese satellites in orbit at a given time.

The ground tracking system is supplemented by stations designed to pick up signals from Earth resources satellites. The original such station was in Miyun (100 km northeast of Beijing), built in 1968 to receive data from the American Landsat and subsequently European, French (e. g. SPOT), and Japanese satellites. Later, ground stations were built in Guangzhou and Urumqi to receive data from the Feng Yun metsats and the American National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) metsats. Chinese Earth observation satellites now transmit to three stations: Miyun (Beijing), Kashi (west), and a new station in the south at Sanya, on the southern tip of Hainan Island, between them forming three circles covering Chinese territory [3].

In addition to controlhng Chinese satellites in orbit, there is an important task in identifying and following satellites belonging to other countries that overfly China. Here, China Satellite Launch and Tacking General Control was set up in 1967, comprising the Beijing Aerospace Command and Control Centre and the Institute for Tracking, Command and Control in Luoyang, down the Yellow River from Xian, to monitor all overflying satellites from low Earth orbit out to 24-hr orbit.

By the 1980s, the space industry became ever more aware of the problem of space debris, which ranged from derelict satellites to discarded upper stages to paint flakes peeling off space equipment, with up to 30,000 items in orbit. There was a small, but real, danger that such debris could pose a hazard to manned flight so, in 2000, COSTIND was given ¥30m (€3m) to begin to assess and track debris in advance of the First manned spaceflight. With the help of computer modeling, a hazard avoidance system was devised that would warn controllers of any debris that might pose a danger to Shenzhou, so that it could be moved out of harm’s way in time.

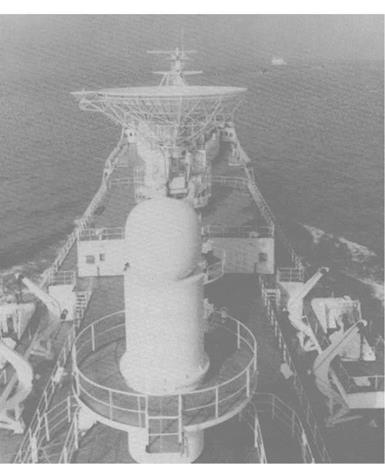

One of the main weaknesses in China’s tracking system was a lack of overseas bases. By contrast, the United States had established from an early stage, with its many friendly overseas partners, a worldwide network of ground-based tracking stations to assist the manned space program and deep-space missions. Lacking allies overseas, the Soviet Union and China had to rely on communications ships, or comships. These were especially important when satellites were flying over southern latitudes, away from their northern hemispheric land masses. In the 1970s, two oceanographic ships, the Xiangyanghong 5 and the Xiangyanghong 11, were brought into use to track the early satellites.

As the space program expanded, it acquired both purpose-built ships and its own institutional form, Satellite Maritime Tracking and Control. The comships are called the Yuan Wang 1, 2, 3, and so on (the words mean “looking far into the distance”, or “long view” for short in Chinese). The first two Yuan Wang were dehvered in 1978 and were the mainstay of overseas tracking in the 1980s. Each was equipped with two 20-m-wide communication dishes, had an ocean-going range of 21,000 km, and could steam for 100 days at a time. Both ships were completely renovated in their home port of Shanghai in 1998-99.

|

Yuan Wang sets out to sea. In the early days, their location was a clue to upcoming space missions. |

Yuan Wang 3 was commissioned in 1995, a big ship of over 17,000 tonnes’ displacement, 190 m long, with nine decks and the appearance of a cruise liner. The Yuan Wang top deck is equipped with s-band antennae, arrays, and satellite dishes with a helideck from which weather balloons are launched. It has c-band and s-band monopulse tracking radars, cine-theodolite laser ranging and tracking, facihties for launching balloons, and communications in the high, ultra-long and ultra-high- frequency bands. Below deck are computer and control rooms, much like mission control on land. It is home to a crew of 350. Over the years, this ship came to adopt Davao in the Philippines as its port away from home, from which it would follow Yaogan missions (Chapter 6). It was joined by the Yuan Wang 4 in 1999, completing a four-strong fleet in time for the first Shenzhou mission. By 2005, it had steamed over 300,000 km on 18 missions. The even larger Yuan Wang 5 first went to sea in September 2007, with a displacement of 25,000 tonnes, constructed in the Jianquan

Launch sites 65

yard in Shanghai. Yuan Wang 6 joined the team on 12th April 2008 and its first operational voyage was the Shenzhou 7 mission.

Comships have drawbacks. They are expensive to operate (Russia decommissioned its fleet for lack of money). Conditions in the southern hemisphere’s seas are quite poor during April-October, which has the effect of limiting missions like the Shenzhou tests to the southern summer and northern winter when they are kinder. Their coverage is actually quite limited, 12% of the orbit for each, albeit at crucial points. For these reasons, China began to consider overseas ground stations, briefly operating a station in South Tarawa Atoll in the Pacific (1997-2003) and then making a mutual access agreement with Sweden for access to its stations in Sweden and Norway (2001).

In 2000, China began construction of its own first overseas land satellite station, in Swakopmund, Namibia. At first sight, this might appear to be a strange location, but retro-fire for a manned spacecraft descending to China takes place as it passes over the coast of south-west Africa. For Shenzhou 1 and 2, China positioned a Yuan Wang tracking ship off south-west Africa to prepare for and monitor these crucial maneuvers. A nearby land station, requiring fewer personnel and not being affected by rough seas, offered a cheaper and more secure alternative. China and Namibia signed an agreement for a tracking station at the Swakopmund salt works, on the road to Henties Bay, completed in 2001. The station comprised satellite dishes, control rooms, administration building, and support facilities. The two dishes – one of 5 m, the other of 9 m – reach 16 m above ground. The station had five permanent staff, expanding to 20 when missions were under way. Later, the overseas ground network was joined by a second overseas station in Pakistan in 2003. A couple of months later, the Italian Space Agency offered the use of its Malindi, Kenya site, providing an additional point of coverage just as the spacecraft go into re-entry (Italy used to launch spacecraft from an oil platform off the Kenyan coast). Later, Dongara, Australia, was added (Chapter 1).