THE TESTING INFRASTRUCTURE

From the opening of its space program in 1956, China established the full range of infrastructure necessary for a comprehensive space program. This comprised:

• a rocket engine testing station;

• static test hall;

• vibration test tower;

• wind tunnels;

• leak detectors;

• radio test facility;

• vacuum chamber.

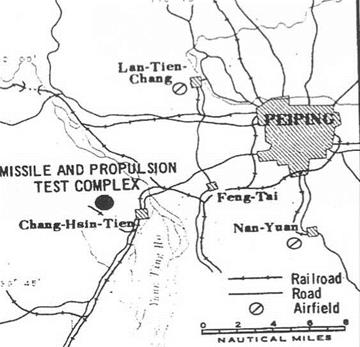

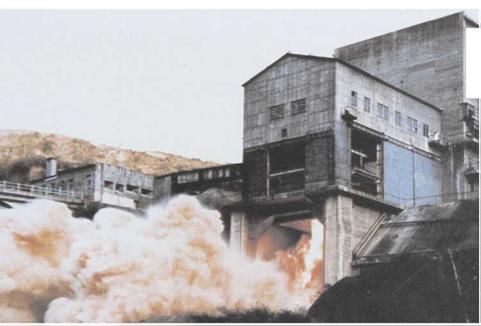

One of the first was the Beijing Rocket Engine Testing station (1958), also called the Fengzhou Test Centre, now the Beijing Institute of Test Technology and formally part of CALT, 35 km from Beijing. The first set of four rocket test stands was completed in 1964 under the direction of Wang Zhiren and she designed them to run up to four engines at a time and simulate ground-level and high-altitude tests. A

|

|

|

large stand was completed in 1969, 59 m high, with a cooling system drawing on a tank holding 3,000 tonnes of water cooling the engines with 35,370 nozzles. Subsequent stands were built for horizontal engine tests. Like Jiuquan cosmodrome, the engine testing station was quickly spotted by overflying American reconnaissance aircraft and satellites. The ideal site for a testing station was a ravine, so that the stand could be built on the hillside and the flames deflected down into the ravine along a concrete outflow.

CALT’s static test hall was, when built in 1963, the largest building in China, taking eight months to construct and involving the driving of 1,300 piles – some as long as 10 m – and two pourings of more than 5,000 m3 of seamless concrete. Entire rockets can be tested there at a time. For the development of the communications satellite, a large vertical dynamic equilibrium machine was developed. Construction of the machine began in 1976 and it was operational five years later. Also constructed that year was a 50-m-tall vibration test tower. On the outside, it looked like an unprepossessing, shabby yellow-and-orange brick grain mill, but it was able to test all the likely stresses an ascending rocket was likely to experience. With 13 floors and 11 working levels, entire rockets were hoisted into place on the stand, gripped by bearing rails on the floors, and then shaken to exhaustion by 20-tonne hydraulic vibration platforms.

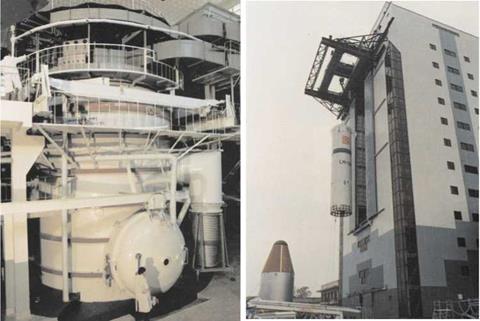

A series of vacuum chambers was built in Beijing and Shanghai in the 1960s, able to simulate up to 10-7 torr (1 torr = 1/760 atmospheres) and later, in the case of geostationary satellites, 10-13 torr. They are located at the Environmental Simulation Engineering Test Station in Beijing and the Huayin Machinery Plant in Shanghai. Here, spacecraft are lowered by crane to be alternately frozen, heated, shaken, and baked in a vacuum. Supercooled helium is the chief agent for freezing the chamber while pumps are used to suck the air out. The test station in Beijing has six chambers, called KM, the largest being 12 m in diameter and 22 m tall. The most recent is the 12-m-diameter KM6 (1998), designed to test the Shenzhou spacecraft. To test against leakages in satellites, the Beijing Satellite General Assembly Plant developed a highly sensitive leakage detector using krypton-85, able to pick up a leakage of 50 microns (half the width of a human hair). For the Long March 3 third stage, the Lanzhou Physics Institute developed a helium mass spectrum leakage detector. To test satellite radio systems, a test hall was built whose primary feature was that it has no metallic components, so it is made entirely of glued red pinewood.

More recently, testing facilities were built for spacecraft and the testing of robotics at Harbin Polytechnical University (2000). Called the Environmental and Engineering Space Laboratory, it is designed to simulate the vacuum and radiation of the space environment, from elements to materials and full-scale spacecraft. For Shenzhou, CAST has a 100,000-class clean room, an anechoic chamber built with the help of European Aeronautic Defence and Space (EADS) Astrium, and a thermal vacuum chamber 24 m tall and 12 m in diameter. There is a Shenzhou simulator and a 10-m-deep hydrotank. China’s first wind tunnels were built in 1959 for the Aerodynamics Research Institute, Beijing, and were first used to determine the air flow and pressure on rockets climbing and staging, and more recently for testing airflow around shuttle-type spacecraft.

|

Vacuum testing facility. Vibration test tower for the CZ-2 |