TSIEN HSUE SHEN

Several names are irrevocably associated with the development of the world’s great space programs, like Sergei Korolev in Russia, Wernher von Braun in Germany, Hideo Itokawa in Japan, and Yikram Sarabhai in India. The father of China’s space program was Tsien Hsue Shen, born in Hangzhou, Zhejiang, in 1911, the only child of an educational official (note that he is sometimes spelt Xian Xuesen: it is the same person). The name Tsien Hsue Shen means “study to be wise” and he attended a primary school for gifted children in Beijing. A model child with an outstanding school record, Tsien subsequently entered the Beijing Normal University High School. At 18, he applied to Jiatong University in Shanghai to study railway engineering, coming third in the nation in the entrance exam. A serious, aloof, immaculately dressed, and perfectly behaved student, Tsien was a man who Uked to study on his own, his only outside interest being classical music (he played the violin). Graduating as top student, with 89 points out of 100, he chose to pursue aeronautical engineering, competing for a scholarship in the United States in 1935. He started at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), staying only a year before moving to the California Institute of Technology (popularly known as CalTech) in Pasadena, where he studied under the great Austro-Hungarian mathematician Theodore von Karman and graduated as doctor in 1939. At that stage, the scientific and technical sector was poorly developed in China and almost all aspiring scientists went abroad to study.

There, five fellow students and associates invited him to join a group interested in what would now be called amateur rocketry. They were a gang of experimenters

buying up spare parts, assembling them, and letting them off in the nearby desert. He was in effect the mathematics advisor to the group, writing his first work on rocketry, “The Effect of Angle of Divergence of Nozzle on the Thrust of a Rocket Motor; Ideal Cycle of a Rocket Motor; Ideal Efficiency and Ideal Thrust; Calculation of Chamber Temperature with Disassociation”, in 1937. Their first, often dangerous, experiments were presented to the Institute of Aeronautical Sciences and written about locally in the student press, where Tsien made some reckless comments about the possibility of eventually sending rockets 1,200 km into space. Rather like fellow rocketeers in Germany and the Soviet Union, their work soon became sponsored by the military, who saw the potential for rockets both to make aircraft fly faster and as ballistic missiles. By 1942, after the United States entered the war, Tsien was working on small solid-rocket motors to help aircraft get airborne; shortly afterwards, he helped to draw up plans for a missile program and later received a commendation from the Air Force for this work. By 1943, Tsien had become assistant professor of aeronautics in 1943 and taught students, though many found his manner intimidating, intolerant, arrogant, over-precise, and unsympathetic. He was one of the co-founders of the famous Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), from where American unmanned exploration of the Moon, the nearby planets, and the outer solar system was to be subsequently guided, and, in 1944, he became the first head of research analysis there.

In May 1945, having been given the temporary rank of colonel of the United States Air Force, Tsien arrived in Germany to survey the Nazi wartime achievements in missiles, especially their A-4 (V-2) rocket. On 5th May, he met the leading German rocket engineer Wernher von Braun, who had just surrendered to the Americans, at the very time when their opposite number in the Soviet Union, chief designer Sergei Korolev, was scouring other nearby parts of Germany on an identical mission. Returning to JPL, Tsien published his wartime technical writing in a book called Jet Propulsion (1946, JPL). After a return to MIT in 1946-48 and a brief visit to China in 1947 (where he married), he became in 1950 the Robert Goddard professor of jet propulsion at CalTech. He gave a presentation to the American Rocket Society in which he outlined the concept of a transcontinental rocketliner able to fly 400 km above the Earth, its spacesuited passengers floating in its cabin as they briefly enjoyed weightlessness – ideas covered in Popular Science, Flight, and the New York Times.

The following year, in 1951, at the height of the McCarthy witch-hunt in the United States, he was accused of being a communist. A period of confusion followed, in the course of which Tsien had his security clearance revoked and was then jailed. The various bureaucratic factions of the American government argued about whether he should be released, jailed, or deported, while his papers were impounded. He was charged that one set of papers comprised secret codes: closer inspection revealed that they were logarithmic tables.

Four years later, Tsien and 93 fellow scientists returned to communist China in exchange for 76 American prisoners of war taken in Korea. Re-entering China through Hong Kong, then a British colony, Tsien and his family were warmly greeted in Shenzhen by the Chinese Academy of Sciences and welcomed by Zhou

|

Tsien in Germany, right, given a temporary military uniform. |

|

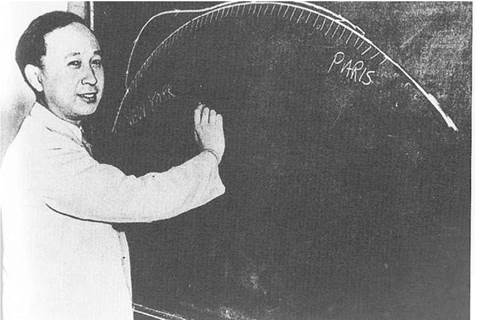

Tsien sketched, in the late 1940s, a spaceplane to fly the Atlantic. |

|

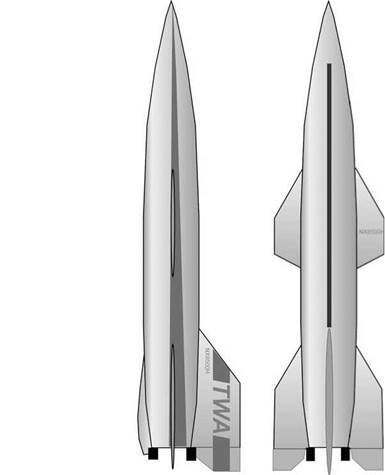

Tsien designed these spaceplanes for suborbital flight. Courtesy: Mark Wade. |

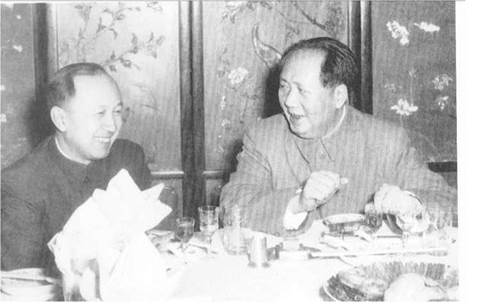

Enlai in a series of homecoming celebrations that culminated in Beijing, just restored as China’s capital city. He brought with him – in his head, since his papers had been seized – the most up-to-date theory of rocketry from the United States. On 17th February 1956, he was entertained by no less than Mao Zedong himself.

However, he had to start virtually from scratch. China in the early 1950s had barely emerged from a long period of great turbulence and destruction – colonial invasions, social unrest, the war with Japan, then the civil war, and finally the communist revolution of 1949. Making bicycles, cars, and trucks represented the limit of China’s industrial and technical capacity – there were no aircraft factories, test sites, wind tunnels, or the type of facilities Tsien had taken for granted in California. His arrival, though, coincided with the adoption by the government of a

|

Tsien welcomed back to China by Zhou Enlai, 1955. |

|

Tsien invited to meet Mao Zedong, February 1956. |

10-year plan, Long-Range Planning Essentials for Scientific and Technological Development, 1956-67, defining priority tasks such as rocket and jet technology, atomic energy, and computers. As part of this, a party and government decision formed the Fifth Research Academy of the Ministry of National Defence on 8th October 1956. This was the sonorous title of the institute that led the Chinese space program, for which the government took over two abandoned sanatoria and requisitioned 156 university graduates to begin work there, putting Tsien Hsue Shen in charge.

Tsien’s first task was to recruit fellow scientists and engineers, mainly contemporaries returning to China from Britain and the United States. Helped by Zhou Enlai, he appears to have been spectacularly successful, for the biographies of China’s space designers looked Uke a graduation list from MIT and CalTech. The roll call of early Chinese space designers came from the United States (Ren Xinmin, engines; Tu Shoue, rocket design; Yang Yiachi, automation; Wang Xiji, recoverable satellites; Tu Shancheng, Shuguang), Britain (Chen Fangyun, electronics; Wang Weilu, rocket design), the Soviet Union (Sun Jiadong, satellites; Tong Kai, navigational and weather satellites), and Germany (Zhao Jiuzhang, space physics) [3].

Zhou Enlai went to some length to ensure that the Chinese communist party should welcome them home and not treat them with suspicion because they had been born in what was termed “the old society” or were not communists. Even still, they recognized that they would need outside help to make progress, so they turned to China’s political ally, the Soviet Union, sending a delegation to Moscow. Under the New Defence Technical Accord 1957-87, the Soviet Union supplied its version of the German A-4, with blueprints and technical documents, while 102 engineers went to the USSR for training. Although quite old technology at this stage, it would take the Chinese several years to build and fire their own version, finding out the hard way that production of a rocket and its many exacting components was a difficult, demanding, and sophisticated task. A program of scientific cooperation was agreed with the USSR Academy of Sciences in February 1960.

Everything changed on 4th October 1957, when the Soviet Union launched the first Earth satellite, Sputnik. The launching should not have surprised the Chinese, for the coming launch had been announced in the Soviet press many times over the preceding three years. Warned or not, the Chinese Academy of Sciences swung into action, setting up observation stations in Beijing, Nanjing, Guangzhou, Wuhan, Changchun, Yunan, and Shaanxi, coordinated by the ancient Zijin Shan Purple Mountain observatory.

On 17th May 1958, awed by Russian rockets which he had inspected during a visit to Moscow and inspired by the performance of the Soviet Union in orbiting a large, 1.5-tonne satellite two days earlier (Sputnik 3), Mao Zedong proclaimed that “China too must launch Earth satellites”. A meeting of the Fifth Academy was convened and Tsien was instructed to build an Earth satellite. It was given a project code number (project 581), as was the project to launch an indigenous version of the German-Russian rocket (1059). Coding has been an important part of the Chinese space program, the digits coming from either the year in question and the project

|

number of that year (e. g. 1955 and 1) or the date of the month (3 31 for the 31st of the third month, March), or from more obscure sources. Table 2.1 lists the coded projects of the Chinese space program.

Despite an initial burst of energy, project 581 soon faltered, the fault being largely that of its instigator, none other than Mao Zedong himself. It coincided with the great leap forward, a period of forced modernization in industry, agriculture, and the

|

211 |

Moon probe (2003) |

|

331 |

Communications satellite (1977) |

|

581 |

Original Earth satellite project (1958) |

|

651 |

Earth satellite project, as renewed (1965) |

|

701 |

Ji Shu Shiyan Weixing (1970) |

|

714 |

Shuguang manned spaceflight program (1971) |

|

863 |

Horizontal scientific research program (1986) |

|

911 |

Recoverable satellite program (1967) |

|

921 |

Manned spaceflight program (1992) |

|

1059 |

Copy the Russian version of the German A-4 (1958) |

|

Table 2.1. The coded projects of the Chinese space program. |

|

Code |

|

Project |

|

China’s first modern rocket, the R-l, based on the wartime German A-4 (V-2). |

economy but which included bizarre campaigns to eliminate rats, flies, mosquitoes, and sparrows as well as to build small steel furnaces in every street. By the following year, the economy was collapsing and milhons were starving, even the designers of the Fifth Academy going hungry. Then came the great Sino-Soviet split, which cut China off from Russian technical and scientific assistance. A rising party official, Deng Xiaoping, finally issued the instructions to cancel the satellite project, but to continue with the missile project. Instead of a satellite, he urged the members of the 581 group to focus on more realistic goals, like building a sounding rocket. This they did, but in the most primitive conditions imaginable. The rocket was hoisted into place by a well winch; the command bunker comprised stacked bales of hay; and, lacking even a loudspeaker, the countdown was done by hand signals. Still, the first sounding rockets were fired in 1959.

The missile required a launch site, the chief concern that it be far inland from spying American planes. An oasis 1,600 km north-west of Beijing was selected – Jiuquan, in a high desert, suitable for its remoteness, low population density, and clear air. The XX corps of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) arrived there in April 1958 to clear the site. Eventually, a home-made Chinese version of the Russian variant of the German A-4 was fired from there on 5th November 1960 and called the Dong Feng 1, or “east wind” 1. By this time, the Russians had gone home and the Americans were overhead in their prying U-2 spy-planes. The Dong Feng later became the name of a series of missiles that constituted the Chinese missile force (Dong Feng 1, 2, 3, etc.) and, four years later, China was able to build an atomic bomb for them to deliver.