SHENZHOU 8: “THE DREAMS OF THOUSANDS”

The next step of the mission was to bring an unmanned spacecraft up to Tiangong. China had never carried out an orbital docking before and, for that reason, was unwilling to risk a crew on a first mission. The Russians had carried out two automatic dockings in 1967 and 1968 before proceeding to a manned one in 1969. The manned Chinese spacecraft, Shenzhou, was well able to fly automatically and

|

|

|

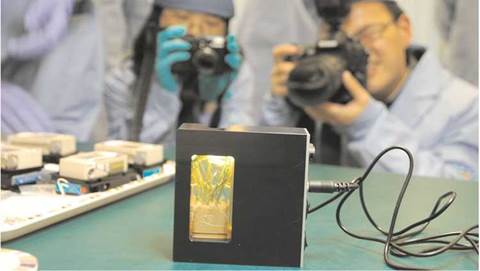

SIMBOX, the German scientific package on Shenzhou 8. Courtesy: DLR. |

the first four flights had been without a crew. Shenzhou itself had a number of improvements compared to earlier models: apart from the rendezvous and docking system, it had an on-orbit design life of 180 days, meaning that it could stay attached to a space station for up to six months. To maintain proficiency in life-support systems, though, Shenzhou 8 carried two rubber-made dummy astronauts. The Soviet Union had likewise flown dummies in advance of its first manned mission, with some unexpected results: when rural villagers reached the landed cabin before the recovery crews, they were found trying to “revive” what they took to be a badly injured cosmonaut!

In the third seat was SIMBOX, an unusual international collaborative experiment. The SIMBOX (Science In Microgravity BOX) was a joint experiment with the German space agency, the DLR. It was a 25-kg, 34-liter experimental box with 40 units for fish, algae, plants, bacteria, worms, and cancer cells, designed to make immunology tests. It was big enough to include a small aquarium, as well as the pumps, lighting, and sensors necessary to support them. Of the 17 SIMBOX experiments, 10 were Chinese, six German, and one joint. It was built in Friedrichshafen in southern Germany by Astrium with seven German universities (Erlangen, Hohenheim, Magdeburg, Tubingen, Freiburg, Hamburg, and Berlin). One German-Chinese experiment was to test the crystallization of proteins. Another experiment involved testing the production of food, oxygen, and clean water in anticipation of long-duration spaceflight.

Shenzhou 8 arrived at Jiuquan on 23rd September even before its target, Tiangong, had left. Lift-off was at 21:58 UT on 31st October, but the following morning locally. Television cameras showed Shenzhou 8 lifting into the night sky, followed by a contrail in the cold upper atmosphere. Look-back cameras on the top stage imaged the bottom stage falling away, to cheers in mission control. Shenzhou was in orbit 10 min later at 261-314 km, 42.8°. Practical astronomers on the ground followed the two spacecraft as they crossed the sky near Beijing as two bright but unblinking, fast-moving stars. Tiangong was like a magnitude + 2 star, the same as Polaris, the North Pole Star.

|

While Tiangong carried flags, Shenzhou 8 carried with it “the dreams of thousands”: in an internet competition, China Space News invited its 12m viewers to

Shenzhou 8 launch. Most Shenzhou missions have launched at night, showing vividly the colors of the fuels used by the rocket. Courtesy: DLR. |

|

contribute their dreams of the future, some 42,891 being selected. They were installed on a microchip, to be recovered after the landing, the dreamers being entitled to download a certificate of authenticity from the site afterwards.

When it entered orbit, Shenzhou was 10,000 km behind Tiangong. By this stage, the station’s orbit had dropped down to 328-338 km. Shenzhou adjusted its orbit five times to close the distance over the following two days. Shenzhou’s radar picked up Tiangong at a distance of 200 km, following which it turned on its optical and laser sensors and microwave radar. On 2nd November, by the time of final approach at an altitude of 340 km, Shenzhou was closing in on the station in darkness at a rate of 20 cm/sec. Once the two docking rings met, Tiangong’s 12 hooks engaged to pull the two spacecraft together and a hard dock was confirmed 12 min later. Docking took place at 17:28 UT on 2nd November. It was Tiangong’s 542nd orbit. They remained locked hard together for the next 12 days.

To make sure that the docking was not just a lucky first, a second test was built into the mission. On 14th November at 11:27, Shenzhou 8 withdrew to 140 m from Tiangong. The purpose of the exercise was to repeat the docking, but in much brighter sunlit conditions, which would be a more demanding test of the optical systems. This exercise took 30 min and the spacecraft were reattached at 11:53 UT. The joined spacecraft could be spotted from the ground as a magnitude 0 star. Pictures of the link-up were relayed to the ground using the Tian Lian 1 and 2 data relays, which, between them, provided unbroken communications. This was the exercise that Liu Wang was to follow seven months later.

On 16th November at 10:30, Shenzhou undocked for the second time, moving away to 5 km before beginning preparations for return to the Earth. After 24 hr, the orbital module at the front was separated and then the service module at the back before the cabin headed into re-entry. Eleven kilometres above the Earth, a static pressure altitude annunciator-controller commanded the drogue, brake, and main parachutes to open, with the cabin fully under the main parachute by 6 km. Shenzhou 8 was down on the ground at 11:32 UT on the 17th, experiments removed, and the cabin swiftly returned to Beijing for analysis. German scientists retrieved their SIMBOX. Shenzhou 8’s orbital module eventually decayed out of Earth orbit on 2nd April 2012.

Tiangong raised its orbit to 360 km on 18th November. Air quality in the laboratory was checked regularly. During the interval, the tracking ships Yuan Wang 3 and 5 returned to their home ports in January, Yuan Wang 6 making it back in February after a 154-day cruise of 50,000 km. In the meantime, there was a good science return from the Tiangong station, reported chief designer Qi Faren. Instruments were giving back readings on space weather, energetic particles, magnetic fields, and atmospheric density, while another technical experiment was testing fuel cells as a power supply for future spacecraft. Fuel cells had been used as far back as 1965 on Gemini 5 to generate electrical power, oxygen, and water, and had subsequently been used in both the American and Russian space programs.

Although the next Shenzhou had been expected at the end of March, in February, there was a flurry of confused reports. First, the mission was off until the summer

|

|

|

and would be unmanned, raising questions that the previous autumn’s maneuvers had been unsuccessful. Eventually, there was a formal statement that the mission would indeed fly in the summer, between June and August, but it would definitely be manned. There had been no particular difficulties with Shenzhou 8, it was confirmed, but no reason was given for the new schedule. Increased solar activity had reduced Tiangong’s orbit, so it was raised on 23rd March back to 364 km. Tiangong readjusted its orbit to prepare for the forthcoming Shenzhou 9 on 26th May and on 11th and 14th June.

The first missions to Tiangong were given dramatic effect by a film distributed throughout China. The film Flying was issued by the August First Film Studio, the cultural wing of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). The studio enlisted the help of the Asia Speed of Light Technology Company to create the special effects, which involved full-sized Shenzhou and Tiangong models, spacesuits, robot arms, and impressive digital simulations of weightlessness and space walks so as to ensure the maximum possible authenticity. Filming took five months and included some sequences shot in Star Town in Moscow. The film was based on the upcoming Tiangong mission but, for dramatic effect, Shenzhou 10 was involved in a collision in space and running out of air. Two men and a woman, led by hero Zhang Tiancong, had to launch within seven days to rescue the stranded yuhangyuan [3].