The heavenly palace

The crowd had been waiting for some time. Hundreds had gathered beside the concrete apron outside the suiting and crew-preparation area. Thirty or forty women were dressed in the bright blues and reds of traditional Chinese dress. They had big red and yellow tom-toms all ready, while the other well-wishers had brought flowers. It was a youthful population, but then most of those who work in the Chinese space program are in their twenties. To help their wait, a band played some lively military tunes. An American astronaut, Leroy Chiao, who had flown into space from both Cape Canaveral and Russia’s Baikonour, once compared the sterile, clinical, crowdless atmosphere of an American launch with the riotous joy of departing from Baikonour. Well, China’s Jiuquan is closer to the Russian tradition.

The doors opened and out stepped into the bright sunshine three astronauts – “yuhangyuan” in Chinese – who were about to embark on China’s fourth, most ambitious manned space mission. Their target was to chase, rendezvous, and dock with an orbital laboratory, Tiangong, which had been circling the Earth since the previous September and set up China’s first space station. Walking a few feet apart in a line were, in the middle, mission commander and veteran Jing Haipeng; on his left, operator Liu Wang, on his first mission; and on his right and the main focus of attention, China’s first space woman, Liu Yang. As they walked stiffly, ever so shghtly hunched forward (spacesuits are not designed for walking), the thronging crowds cheered and waved their flowers while the band struck up a quicker march. The three astronauts carried a small air-conditioning box, like a workman’s toolbox, as they walked along the crowd and waved. The three stopped to give a peremptory report to the commander and boarded their bus. Five buses set out for the pad, preceded by a jeep and motorcycle escort, down the green-lined avenue near the astronaut quarters. More crowds lined the route as the band played on, others rushing forward along the grass verge to keep up with the slow convoy and take pictures.

The convoy then arrived in the cool shadow of the launch tower, a huge structure of girder, levels, and scaffolds. Assistants in blue coveralls and face masks helped the astronauts out. The three stood together, reporting to the state commission, waved, and walked forward into the base of the pad to take the lift to the top. The lift

B. Harvey, China in Space: The Great Leap Forward, Springer Praxis Books,

DOI 10.1007/978-l-4614-5043-6_l, © Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013

|

The crew of Shenzhou 9 steps forward to leave the dressing area for the bus bringing them to the pad. Left to right: Liu Yang, commander Jing Haipeng, and operator and newcomer Liu Wang. Courtesy: Press Association. |

brought them up the vast structure. They emerged from the lift, to be greeted by red – uniformed assistance crew.

Their Long March 2F rocket had been in Jiuquan launch center for two months now. In early April, it left its assembly room in Beijing, the workers standing to attention and saluting as it rolled out on the railway line that came right into the factory. It was then put on the flat of its back for the long, two-day journey to the north-west, heading into the desert of Gansu, to Jiuquan, the town meaning “oasis” that marks the end point of the Great Wall. The rocket reached the launch center on 9th April, preceded by the Shenzhou manned space cabin that would be lifted by crane to its top.

But who would fly? China had recruited three groups of astronauts. The first were selected in April 1971 on an abortive, hopelessly ambitious and quickly abandoned attempt to put astronauts into space in the 1970s. When the manned space program was restarted in the 1990s, 14 astronauts were recruited and from this group was drawn the mission commander Jing Haipeng, aged 45. He had already been in space before on Shenzhou 7 four years earlier, flying on the mission for China’s first space walk, and had been promoted to brigadier. Also drawn from this group was Liu Wang, at age 42 its youngest member, who, before that, had served six years in the Air Force with over 1,000 hours’ flying time and was also a brigadier. China had recruited a third group in 2010 – five men and two women, all Air Force pilots. In December 2011, the selectors had identified, from this pool of Groups 2 and 3, seven men and two women who would fly the next two missions, Shenzhou 9 and 10. Originally, the first crew was to comprise three men and the second crew (Shenzhou 10) would include a woman but, in March 2012, chief designer Qi Faren announced that a woman would fly on Shenzhou 9. Who would she be?

There had been two finalists: Air Force pilots Major Yang Waping, aged 32, and Major Liu Yang, aged 33. Their identity had become known the previous year when postage stamps of their historic mission had been released accidentally prematurely. There had been quite a row, it seems, about their final selection. Liu Yang was the best connected and married to another Air Force pilot. The selection led to lively internet posting and blogs about the decision and it is reported that Wang Yaping’s father, Wang Lijun, posted a blog expressing his concerns that all the media attention would lead to his daughter’s “losing the flight” – but the post was removed, we do not know by whom, within 24 hr. In the end, Liu Yang was selected and the announcement had been made the previous day. She proved a good choice, being personable with the media, and it was made clear that Wang Yaping would get her chance on a later Shenzhou mission. Even as they boarded their bus, their backup crew stood ready to take over if one became suddenly ill, but their members must have known that their chances were fading fast. The backups were, aside from Wang Yaping, mission commander and Shenzhou 6 veteran Nie Haisheng, and another member of the second group, Zhang Xiaoguang.

Their spacecraft, Shenzhou 9, had been fuelled up two weeks earlier on 29th May. Stacked onto its Long March 2F rocket, they had rolled out to the desert launch pad

|

Liu Yang, China’s first space woman, soon to become the most celebrated woman in contemporary China. Courtesy: Press Association. |

|

Shenzhou’s Long March 2F rocket, with the vehicle assembly building in the background. Courtesy: DLR. |

on 9th June. The two crews for the mission arrived from Beijing that very day for final preparations and training. The last thing that Liu Yang did before leaving was to phone her mother-in-law to tell her of the upcoming flight and not to worry.

China had never launched a Shenzhou spaceship in summer before and weather was a concern in the days up to the launch, for two reasons. First, the summer heat could well trigger off storms that would delay a launch; and, second, although the nitric acid fuels of the rocket can be stored for a long time at room temperature, they begin to become a problem when temperatures rise. Weather balloons were released in the days up to the launch to test the air for its stability: so far, so good. The crew boarded the rocket two hours before launch. They entered through the orbital module at the top, squeezing slowly and carefully into the lower, beehive-shaped descent module, Liu Yang in the left seat, Liu Wang in the right seat, and commander Jing Haipeng coming down the tunnel last to sit in the middle. They settled down for the wait as the final checks were completed.

As was now the norm, the launch was covered live on Chinese television. The white rocket with the Chinese flag could be seen against the brown desert and flat horizon, stacked beside the huge structure of its blue and light-green steel tower. No more than in Baikonour, they do not do countdown clocks in Jiuquan, so watchers had to listen to the audio commentary to know how close they were to launch (though the launch time of 18:37 local time had been given a week earlier).[1] The one – minute mark was announced and the small red girders of the swing arms moved back from the rocket. It now stood on its own. At 10 sec, the final countdown was called in Chinese.

The cameras zoomed in at the base of the rocket. There was a sudden thud as the nitric fuels ignited and, within a second, the rocket began to rise. The ascent of the Long March 2F is initially slow and dead straight but, after half a minute, it begins to bend over and accelerate in its climb. Ground cameras caught it as it sped upward. Infrared cameras showed the bright engine lights burning. The events of the third minute into the mission are quite dramatic. First, at 130 sec, the pin-shaped escape tower is fired off the top and tumbles away. At 160 sec, the four strap-on boosters spin away, followed by the entire first stage, which drops back. After a brief pause, the second stage ignites and, at 200 sec, the payload fairing is blown off the top. Natural light now floods into the cabin. An inside color camera view showed commander Jing Haipeng in the middle, Liu Yang on his left, and Liu Wang on his right, their feet tucked up in their contoured seats. They appeared relaxed, with no vibration evident.

A bow-shaped shock wave formed around the rocket as it headed into the far distance, a mere pin-prick now barely visible from the ground where, meantime, a cloud of brown smoke had risen from the pad. The rocket now tracked south-east, well south of Beijing, to cross the Chinese coast at the Yellow Sea and head over the Pacific. It had now reached altitude and, as the second stage burned, the rocket was essentially horizontal, building up the speed necessary to achieve orbital velocity. Look-back cameras gave almost vertiginous views of the ground falling away and the horizon turning from a flat line into a curved shape. Within eight minutes, Shenzhou 9 was almost in orbit. Next, cameras on the rocket showed the separation of the cabin from the rocket, as a shower of water droplets spilt free. They had reached orbit, to applause in mission control while the three astronauts waved and clasped hands in celebration. Jing Haipeng’s clipboard could be seen floating free when they became weightless. The initial orbit was 261-315 km, exactly as hoped for.

No sooner had they arrived in orbit than television cameras on the outside of the craft showed the two solar panels stretch open. At the time, Shenzhou 9 was passing over the Yuan Wang 5 tracking ship and there were brief interruptions as it acquired the signal, the images from the cabin occasionally breaking up. Had the panels failed to open, the crew would have had no electrical power and been obliged to make an emergency landing an orbit later in an ellipse marked out in western China.

They took off their spacesuits and moved into blue coveralls. They opened the tunnel into the larger, more spacious orbital module at the front. Crammed into Shenzhou were experiments and 300 kg of water and food. Media coverage of the launch was intense in China, inevitably focused on Liu Yang, now set to become one of the most famous women in China’s history. Media found their way to her home town to interview her family, school mates, and Air Force colleagues. Liu Yang was the 56th woman in space, but the launch made China only the third country to have launched a woman into space by itself. She was launched on the 49th anniversary, to the day, of the first woman in space, Valentina Tereshkova, in 1963.

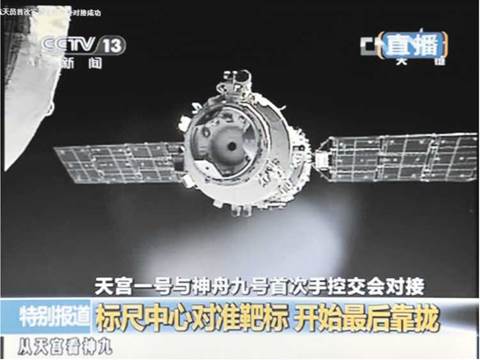

The next two days were uneventful as Shenzhou chased Tiangong in orbit. Three changes of path were required for Shenzhou to close the distance with Tiangong, the first being to lift the low point from 261 to 315 km. The following day, at 14:40 UT on 17th June, Shenzhou adjusted its orbit to 315-326 km. By the morning of the 18th, Shenzhou had closed the distance to the station and both were circling the Earth at 343 km. At 53-km distance, Shenzhou began pinging Tiangong with its radar. Black-and-white cameras had been installed on both Tiangong and Shenzhou, following the one approaching the other on a split screen at mission control. As Shenzhou came in, entirely under automatic control at 20 cm/sec, the petals of the docking mechanism became ever clearer, opening like jaws to close with the ring on Tiangong.

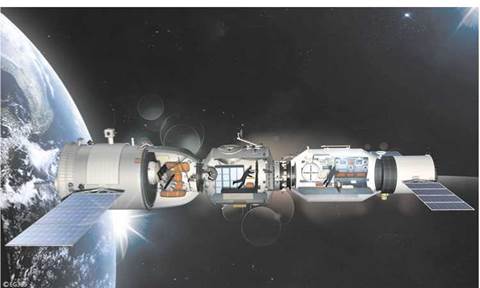

There was a shudder as the two came together at 06:08 UT on 18th June. Air was squirted into the docking tunnel and the pressures of Shenzhou, the tunnel, and Tiangong equalized. Three hours later at 09:10, when the combined spacecraft were back over Chinese territory, the hatch was opened into Tiangong and Jing Haipeng and Liu Wang floated through, leaving Liu Yang temporarily in Shenzhou. The inside of Tiangong was a long cylindrical box shape, with small straps installed at points all along the four walls for the astronauts to hold in weightlessness. On one wall, there were three computer screens for the astronauts to operate while on

|

|

another was a Chinese flag. There was a food heater and a hidden toilet. After a short period, all three astronauts presented themselves together in front of the television camera to report and salute, to stormy applause in mission control. The Tiangong station was declared operational: China had, at last, built an orbital space station. President Hu Jintao came to mission control to formally congratulate them in a telecast.

Every evening, Chinese television followed the progress of the astronauts as they worked in the laboratory in their blue coveralls. Liu Yang exercised on a bicycle which could be unfolded from a wall. Her fellow crewmembers operated the computer and conducted experiments. On the 21st, they spoke to their families in ground control. The normal pattern was for two to sleep in Tiangong and one in Shenzhou. For experienced space watchers, the cabin was smaller than the Soviet Salyut station and nearer to the size of the Spacelab module that used to be carried by the Space Shuttle.

They carried out 10 medical experiments. Ground controllers reported on the food they were eating, such as rice pudding. Whereas previous space travelers relied on biscuits and toothpaste-tube food, this mission boasted a much-improved menu with 70 different items, mainly traditional Chinese food. On the new menu were sweet-and-sour, bean curd, spicy food, and rice with fried dishes. Besides Uve communications, they communicated to the ground by e-mail, with photos, text, and videos. Liu Wang could be seen playing the harmonica to send birthday greetings to his wife. Liu Yang could be seen with her laptop. According to her, weightlessness made her feel “like a fish swimming freely in water”. It was a week of scientific achievement for China because, that very week, the submersible Jiaolong was exploring inner space, diving 6,965 m deep into the Marianas Trench in the Pacific.

After a week on board, the time for one of the most important tests of the mission came: undocking and then re-docking manually. Manual docking was an important maneuver to test should, on a future mission, the automatic control system break down. Jing Haipeng and Liu Wang had rehearsed the maneuver 1,500 times in simulations, but real events can always throw up surprises. First, on the 22nd, Tiangong’s orientation system was turned off and Liu Wang went into Shenzhou to test the maneuvering engines of the smaller spacecraft. The next day, 23rd June, was the big day, for they faced the challenge of undocking from the station, retreating to a distance of 400 m, and then re-docking, but under manual control. It coincided with the day of the Dragon Boat Festival, in advance of which they sent greetings to all those involved. Then, the three astronauts put on their spacesuits (a precaution against depressurization), squeezed back into the descent cabin of Shenzhou, undocked, and backed away under automatic control to a distance of 400 m. They separated at 03:10 UT.

A screen split three ways in mission control showed the two spacecraft pinging one another on the bottom, with data readout superimposed on the screen; the crew cabin with the three astronauts in their protective spacesuits but visors up on the right; and the spacecraft moving together in black-and-white images on the left. Liu Wang, called “the operator”, was in charge and he could be seen at the controls. Back on the Earth, ground controllers could be seen in their white doctor’s coats, with mission badges, headsets, and microphones.

|

The configuration of Shenzhou and Tiangong docked in space. Courtesy: Press Association. |

At 140 m, the manual control system was activated and Shenzhou began to move forward. Displays clicked off the closing distances. The global tracking map indicated that the maneuver was taking place over the Horn of Africa. Now, the laser radar detector was switched on. At 100 m, Tiangong grew in size on the screen as the two spacecraft drew together at 40 cm/min. Tiangong was poorly lit but, when the screen switched to image Shenzhou, it was sharply visible, its solar panels shining in the bright sunlight over the curvature of the Earth. There was a continuous chatter of the mission controllers in the background. The cross of the docking marker was outlined in the cross-hairs of the closing Shenzhou’s camera. Shenzhou was imaged in beautifully clear detail as they closed the final meters. The connection was made absolutely smoothly, Shenzhou yawing just slightly after they met at 04:48 UT, 12:48 Beijing time, after an hour and a half flying separately. They then pulled together for the final tightening and hard dock. Within minutes this time, they re-entered the laboratory. Mission controllers allowed themselves a moment of applause, some giving the thumbs-up, before getting out of their seats to shake hands with colleagues, broad smiles all round.

Late on 27th June, the astronauts boarded the Shenzhou 9 cabin for the return to the Earth. The hatch into their orbital home was closed at 22:37 UT. There was a slight jolt as Shenzhou uncoupled at 01:22 UT early the following morning, the 28th, and moved steadily away. Liu Wang used manual control to back Shenzhou away to 5 km from Tiangong. At 04:35, he moved the spacecraft into a new orbit for re-entry. They had almost a day on Shenzhou to themselves as they prepared for landing early the following morning, 29th June (on the Russian Soyuz returning from the International Space Station (ISS), re-entry normally takes place only two orbits later).

The critical events took place over the South Atlantic Ocean approaching the coast of Africa. As Shenzhou came over one of the tracking ships at 01:16 UT, the orbital module was released: it would orbit the Earth for a couple of months before burning up in the upper layers of the atmosphere. A minute later, the retrorockets burned, the end of maneuver reported to the Chinese ground tracking station at Swakopmund on the Namibian coast. Shenzhou now began a curving descent over Africa, passing over the Malindi tracking station in Kenya and out over the Indian Ocean, with another tracking ship stationed off the Pakistan coast. Moments later, at 01:37, the descent module was released. The cabin was now on its own, 140 km over the Earth, tracking towards the next station in the chain, Karachi, Pakistan, its pathway taking it between Islamabad and New Delhi. Remarkably, cameras picked up the whole re-entry on infrared, identifying two big trails in the high atmosphere. The largest, a blob-shaped trail, was the service module, which grew brighter, flashed, broke up, and dissolved. Ahead raced a longer, steadier trail, like a meteor – the tiny Shenzhou cabin with its crew of three on board. Going through re-entry was like being inside a blowtorch, they all say, as the cabin is enveloped in gases that glow red and orange and yellow from the great heat. At the end of the four-minute blackout, the cabin had fallen to an altitude of 40 km above the Earth. Over northern China, the cameras continued to follow the spacecraft, the dark background turning to a very light blue as they spotted first the drogue, then the main parachute come out at around 10,000 m. The Shenzhou cabin could be seen twisting back and forth as it settled under the parachute ropes. It had 10 min to drift to the ground.

Mil-type helicopters were already in the air and their crews quickly spotted the descending cabin. The descent could now be followed from three spots: from the ground, at long range from a first helicopter, and then close up from a second that hovered over the parachute to observe the descent from above – a much more sophisticated operation than the norm in Kazakhstan when Soyuz comes down. The cabin was caught in a breeze and developed quite a side motion. It could now be seen venting unwanted fuel so as to reduce the risk of an accident at touchdown. Shenzhou could be seen clearly as it tracked over grasslands, criss-crossed by tracks and minor roads where rescue jeeps had gathered – including a truck with local farmers who had escaped the security cordon and saw everything. Shenzhou’s shadow could now be clearly seen against the ground, passing over a small river and, when the cabin moved to meet its shadow, it was obvious that touchdown was close. Wham! The cabin’s tipped into the ground, the four retrorockets fired in a puff of black smoke, the cabin tumbled end over end, and came to rest on its side. It gouged out quite an impression in the clay. A guillotine cut the parachute, which deflated and drifted lazily to the ground. Shenzhou had come to rest on a sandy slope beside a river in a small valley, on a desert floor of grasses and small shrubs. Touchdown time was 10:02 local time, 02:02 UT, at 42.2°N, 111.2°E. Blown by the strong wind, they came down some 16 km from the precise aim point, but still within the 36 x 36-km landing ellipse, about 1,000 km downrange from Jiuquan from where they had been launched two weeks earlier. There is a backup landing site just south of Jiuquan should the crew make a steep, ballistic re-entry. Both points were closed off to aircraft as the moment of landing approached.

|

After landing, the crew of Shenzhou 9 relaxed in directors’ chairs, the cabin behind them. Courtesy: Press Association. |

The rescue teams rushed forward, dressed in red coveralls, the medical teams in white coveralls. They opened the hatch, which was close enough to the ground, so the crew must have been hanging out of their seats, restrained by their straps, facing downward at 45°. Medical rules require the crew to remain in the cabin for readjustment to gravity for up to 75 min, quite different from the standard Russian practice in which the crew is normally taken out straightaway. Rescuers passed in bottles of water, before they unstrapped and took the crew out one by one. There was another round of applause in mission control as Liu Yang emerged, smiling cheerfully, and the three were then placed side by side in directors’ chairs a few meters from the cabin. Three rescuers came forward and presented the crew, who saluted from their sitting position, with flowers. The three clasped their hands together in the air to a third round of stormy applause in mission control, where controllers had now been joined by Prime Minister Wen Jiabao. This formally marked the end of their mission, for they could rise from their seats to congratulate their co-workers. Rescuers then lifted the three crewmembers together into a large waiting helicopter for an initial airborne medical examination and later return to Beijing. The mission had lasted 12 days 15 hr – more than twice as long as the previous longest Chinese space mission. They were sent for two weeks’ rest and debriefing, emerging to give press interviews on 16th July.

The mission had gone entirely smoothly, with no hitches, all the key points reported live in the Chinese media. In the space of two weeks, China had made its

|

A hero’s welcome for Liu Yang, helicopter in the background. Courtesy: Press Association. |

longest space mission, sent its first woman into space, carried out first an automatic docking and then a manual one, and occupied its first space station – and this was only its fourth manned spaceflight. There was much cause for relief and celebration. No sooner was the mission over than China announced that Shenzhou 10 would repeat the mission early in 2013 [1]. Tiangong continued to circle the Earth, moving into a higher orbit of 354-365 km to be ready for another docking in six months’ time, while Shenzhou 9’s old orbital module was left behind in 333-354 km orbit, where it would eventually bum up.

Thus, China established its first space station in orbit around the Earth in summer 2012. But it was not the only station circling the Earth. Even as the three yuhangyuan left Tiangong, a much larger 470-tonne space station kept them company, albeit in a different orbit. Crewed by six astronauts and cosmonauts, its solar panels so big and bright as to make it the most visible object in the night sky, it was the ISS. By coincidence, three members of the ISS crew returned to the Earth only two days later, in another desert further to the west in Kazakhstan. So why had China built its own orbiting space station and how?