The Formation of The Aerospace Corporation

From the beginning of the WDD, aircraft industry leaders complained bitterly about R-W’s insider position. They believed that the ideal approach to weapons development was for the air force to let prime contracts to a single integration contractor, a position supported by the air force’s own regulations. These stated that the air force should hire a single prime contractor to develop, integrate, and test a weapon system, unless no company was qualified to perform the task. In this case, the air force itself could act as prime contractor. The latter position was Schriever’s justification for his approach to the ICBM program, with the important modification that the air force would instead hire a third party to direct technical coordination of the integration task. Industry leaders also pointed out that in R-W, the air force was creating a new, powerful competitor with close ties to air force planning and a concomitant edge in bidding.48

Normally, R-W should have been controlled by the air force in the way that any other contractor would have been. However, the air force had hired R-W to act as the air force’s technical assistant for ICBM development, in which position R-W personnel acted with virtually the same authority as the government. In 1954, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Research and Development Donald Quarles, formerly of Bell Labs, had insisted that R-W personnel be given “line” responsibility, with full authority to direct contractors, instead of “staff” status, where they would merely be advisers. This mirrored his experience at Bell Labs, which acted as the technical direction authority to AT&T’s manufacturing arm, Western Electric. Bell Labs also performed this role with other contractors, sometimes on behalf of the government on high-priority military programs. This powerful position required that AT&T acquire sensitive data from other companies. As a regulated monopoly, AT&T could legitimately act in this capacity, as it essentially had no competitors.49

Caltech’s JPL and MIT’s Radiation Laboratory also acted as technical direction groups for the government, but these academic nonprofit institutions were little threat to industry. However, R-W was neither a nonprofit institution nor a regulated monopoly, and in fact it competed for other projects against the same companies that it monitored on the ICBM program. Existing aircraft firms vigorously campaigned against the air force’s unusual relationship with the upstart company.

To protect his organization from criticism, Schriever enforced a hardware ban on R-W to keep it from acquiring lucrative hardware contracts on any programs in which it was the technical direction contractor. R-W ‘‘walled off’’ the technical direction work of STL from the rest of the company. Continuing concerns led R-W to establish a physically separate location for its headquarters — in Canoga Park, California. These measures did not satisfy industrial leaders, who continued to lobby against the company.50

Despite the clamor and the ICBM hardware ban, neither Ramo nor Wooldridge believed that R-W could grow without manufacturing capabilities. They grasped every opportunity to expand manufacturing by aggressively pursuing hardware production products and contracts outside the ballistic missile program. These included process control computers, semiconductors, and a variety of aircraft and air-breathing missile components. Aggressive pursuit of hardware contracts paid off, as R-W received permission to build ballistic missile hardware to test ablative nose cones built by General Electric. Strongly backed by Schriever’s technical director, Col. Charles Terhune, STL then built the Able 1 lunar probe launched in August 1958 and the Pioneer 1 spacecraft launched by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) in October 1958. These activities fomented even more severe industrial protests, as the hardware ban against R-W evaporated.51

Expansion on these and other ventures such as semiconductors stressed R-W’s finances. Ramo and Wooldridge leaned on their original investor, Thompson Products, for cash to expand facilities and capital equipment, and the ensuing negotiations led to an agreement that resulted in the merger of the two companies effective October 31,1958. The new combination, Thompson- Ramo-Wooldridge (TRW), became the aerospace giant that the older aircraft companies had feared.

TRW executives recognized the awkward position of STL in the new company. STL handled TRW’s space business, including both the technical direction tasks for the air force and STL’s budding space manufacturing businesses. Because of the air force connection, STL would always be vulnerable to charges of conflict of interest. To minimize this risk, TRW executives established STL as an independent subsidiary corporation with its own board of directors chaired by Jimmy Doolittle, a war hero with impeccable credentials and impressive ties to the air force and NASA. No TRW board member or senior manager sat on STL’s board. TRW executives recognized that they might have to divest STL, and through this reorganization they were prepared to do so.52

Although TRW was prepared to divest STL, neither Schriever nor TRW really wanted this to happen. TRW enjoyed significant profits from STL, and Schriever wanted STL’s experienced personnel directing the technical aspects of the air force’s ICBM and space programs. However, STL’s increasing involvement with space projects and hardware development fueled industry complaints, leading to congressional hearings in February and March 1959.

These hearings, chaired by Rep. Chet Holifield from California, featured vehement attacks against STL’s ‘‘intimate and privileged position’’ with the air force and equally strong defenses by Schriever and by TRW executives Simon Ramo and Louis Dunn. It became clear even to Schriever that as long as TRW acquired competition-sensitive technical information from other aerospace firms through STL, the clamor would continue. A plan to sell STL to public investors fell through when Air Force Secretary Douglas vetoed it on the grounds that STL would remain a problem as long as private owners used STL to make a profit. The Holifield Committee’s final report seconded this idea and urged that STL be converted into a nonprofit corporation like RAND and MITRE. Schriever reluctantly agreed, leading to the formation of The Aerospace Corporation on June 4,1960.53

At Schriever’s insistence, STL continued systems engineering and technical direction for the ballistic missile programs for the near future, but all others transferred to Aerospace. Dr. Ivan Getting became Aerospace’s first president, and a number of STL personnel transferred to the new corporation. This ended the controversy about TRW’s insider position with the air force, but as industry had feared, there was a powerful new competitor with which to contend. Aerospace became one of a growing breed of nonprofit corporations that served the air force and other military organizations.

Systems engineering, which required the coordination of all elements of the technical system, could be performed by a prime contractor for the system, by the air force itself, or by a nonprofit firm that had no interest in competition. The experience of R-W showed that a profit-making corporation could not act on behalf of the U. S. government to coordinate or control the efforts of its competitors. The function of systems engineering had to be contained within the government itself, a neutral third party hired by the government such as Aerospace or MIT, or a prime contractor. With this controversy settled, the air force could now standardize systems management as its primary R&D method across all of its divisions.54

Standardizing Systems Management

By 1959, ongoing deliberations at air force headquarters were under way regarding the applicability of Schriever’s ‘‘Inglewood model’’ to the rest of the air force’s development programs. A senior committee headed by the AMC commander, Gen. Samuel Anderson, agreed that the air force should adopt the methods used in Inglewood, with the planning and implementation of new projects on a systems, or ‘‘life cycle,’’ basis. Planning for the entire system would occur up front, and project offices would have the authority to manage development, including funding authority. However, the committee split into three camps regarding the organization, advocating positions ranging from minor modifications to radical reorganization. In June 1960, the Air Staff selected the least ambitious plan, which did include installation of new regulations based on Schriever’s organizational processes, to be used on all the air force’s major development programs.55

The 375-series regulations for systems management originated with one of Schriever’s officers, Col. Ben Bellis, who headed an effort to document the procedures developed in Inglewood. After a series of reviews, the new regulations for systems management appeared on August 31,1960, and were applied to the air force’s major projects for missiles, space, aeronautics, and electronics. Subsequently revised and extended, these regulations became the institutional backbone of the new, Inglewood-inspired R&D system.56

Under the new regulations, the system program director gained significant authority. The air force required that the program director create and gain approval of a single document known as the System Package Program. Each System Package Program provided information on cost, schedule, management, logistics, operations, training, and security.57 The 375 regulations formally applied the ARDC-AMC project office concept across all air force major acquisition programs.

The more radical ‘‘Schriever Plan’’ to manage the air force’s R&D had been shelved by Anderson’s committee in 1959, but it gained new life in 1961 when Robert McNamara became secretary of defense. McNamara, trying to resolve the controversy over which service should gain the coveted military space mission, looked for evidence of managerial and organizational expertise to determine which service should lead space efforts. With several hints from the McNamara camp that the Schriever Plan would help the cause, Air Force Chief of Staff Thomas White approved it. Secretary of the Air Force Eugene Zuckert and McNamara signaled their pleasure by conferring all space research to the air force in March 1961.58

The Schriever Plan reallocated the procurement activities ofAMC to a new organization that also included the development functions of ARDC. ARDC was abolished, its place taken by Air Force Systems Command (AFSC), which came into being on April 1, 1961. Schriever, appointed the first commander of AFSC, now managed all of the air force’s major development programs in four divisions: the Ballistic Systems Division in San Bernardino, California; the Space Systems Division in El Segundo, California; the Aeronautical Systems Division in Dayton, Ohio; and the Electronics Systems Division in Lexington,

The air force’s Ballistic Systems Division and Thompson-Ramo-Wooldridge’s Space Technology Laboratory were in the center of a vast network of government and industry organizations, all of which learned aspects of systems management. ‘‘BSQ’’ represents the Ballistic Systems Division, and ‘‘SE/TD’’ stands for systems engineering and technical direction, the main function of STL. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Massachusetts. Ascending to command over all of the air force’s large acquisition programs, Schriever’s presence ensured the spread and enforcement of the 375 procedures.59

Standardization of R&D in AFSC went beyond the 375 regulations. By mid – 1961, Schriever’s organization molded status reporting into a highly sophisticated system, known as rainbow reporting because it presented each element of the system on pages of different colors in a small, brightly packaged booklet. Over the next few years, the rainbow reporting system evolved to include yearly and monthly milestone schedules, government and contractor financial data, contractor manpower data, reliability data, procurement data, engineering qualification data, and the so-called PRESTO procedures for problems needing immediate attention. They also specified acceptable formats and technologies for presentations to ensure commonality, helping the top-level managers to judge the programs on a consistent basis.60

With the establishment of AFSC, the Inglewood model of systems management, including configuration management, became the dominant model for large-scale programs. In April 1961, Schriever’s authority and influence reached its apex, as he presided over all major development programs in the air force, using standardized methods of his own making.61 What Schriever and others did not foresee was that just as the air force could use systems management to control contractors and its own officers, so too could the DOD use it to control the air force.

McNamara, Phased Planning, and Central Control

Within the DOD, the Office of the Secretary of Defense grew in power from 1947 to the mid-1960s. Over the years, the office progressively pulled critical decisions up the hierarchy, subordinating service interests and rivalries. Benefiting and exploiting this trend to the fullest was John F. Kennedy’s appointee to the office, Robert McNamara.62

McNamara trained at the University of California, Berkeley, and taught business courses for a short time at Harvard before World War II. During the war, he performed statistical analyses for army logistics, determining the quantities of replacement parts needed based upon statistical assessments of combat and operations. After the war, he joined Ford Motor Company, tagged as one of the mathematically trained ‘‘whiz kids’’ that reformed Ford’s disorganized finances and helped turn the company around. He rose quickly, eventually becoming president.63

Famous for his faith in centralized control implemented through quantitative measurement, McNamara took advantage of the authority granted to the Office of the Secretary of Defense by the Defense Reorganization Act of 1958. This act gave the secretary of defense the authority to withhold funding from the services and transfer assignments between the services. Upon his appointment to the office, in the spring of 1961 McNamara initiated a series of more than 100 studies known as McNamara’s 100 trombones, or the 92 labors of Secretary McNamara. The services readily complied with this request, expecting the novice secretary to get bogged down in conflicting piles of recommendations.64

Without waiting for completion of the studies, McNamara also installed RAND chief economist Charles Hitch as the DOD comptroller. Given McNamara’s background as a Ford financial manager and Hitch’s qualifications as an economist, it was not surprising that they considered economic criteria to be foremost in making decisions for future weapon systems. Hitch’s Program Planning and Budgeting System required that life cycle cost estimates be performed before deciding whether to develop a new weapon system. This agreed with the result of one of McNamara’s studies — “Shortening Development Time and Reducing Development and Systems Cost’’—which claimed that ‘‘reducing lead time and cost’’ should be given the same priority as improving performance. It deemphasized the relentless push to higher technical performance and required that feasibility and effectiveness studies calculate technical risks and cost-to-effectiveness ratios.65

Following up on this study, in September 1961 McNamara assigned the task of improving R&D management to John Rubel, the deputy director of defense research and engineering. Rubel established model programs whose methods could then be copied throughout all of the services, starting with the air force Agena, TFX fighter, Titan III, and medium-range ballistic missile programs. Rubel required a ‘‘Phase I’’ effort to develop a preliminary design. This would ensure ‘‘that the cost estimates for the subsequent development effort’’ were ‘‘based on a solid foundation.’’66 The preliminary design effort would generate ‘‘a set of drawings and specifications and descriptive documents’’ to describe management methods, including schedules, milestones, tasks, objectives, and policies. Rubel had no reservations about forcing industrial contractors to organize and manage their projects in the way he wanted. If they wanted the job, they had to conform.67

He made clear in the request for proposals that go-ahead for Phase I did not constitute program approval. Previously, award of a preliminary design contract constituted de facto project approval for development and production. This was no longer true. Only the secretary of defense could approve a project, and he would not do so until completion of Phase I and a program review.68 According to Rubel, ‘‘The fact that improved definition is required before larger-scale commitments are undertaken is neither surprising nor unique, although it is true that on most programs this definition phase has been less clearly identifiable because it has been stretched out in time and interwoven with other program activities such as development, model fabrication, testing and, in some cases, even production.’’ Rubel did not believe that a program definition phase would slow high-priority programs. ‘‘In fact,’’ he wrote, ‘‘our real progress should be accelerated as the result of obtaining a better focusing of our efforts.’’69

The phased approach brought several benefits to upper management. It promised better cost, schedule, and technical definition. If the contractor or agency did not provide appropriate information, management could cancel or modify the program. Organizations therefore made strenuous efforts to finalize a design and estimate program costs. The preliminary design phase provided management with a decision point before spending large sums of money, making projects easier to terminate and contractors easier to control.

By 1962, studies by Harvard and RAND economists had shown that DOD weapons projects had consistently large overruns and schedule slips, with missile programs having the worst record. The RAND study showed that for six missile projects, costs overran by more than a factor of four, with schedule slips greater than 50%. Other projects showed smaller slips, but all types averaged at least 70% cost overruns, and the average was more than 200% (triple the original cost estimates). The military was clearly vulnerable to criticism on cost issues, and McNamara efficiently exploited this weakness. His Program Planning and Budgeting System required that all of the services create five- year projections of programs and their costs, allocated not by specific services but rather across broad categories such as strategic offense or defense.70

Schriever sensed the change in national priorities and saw the impact of McNamara’s reforms. Replacing ‘‘concurrency,’’ ‘‘managerial reform’’ and ‘‘cost control’’ soon became the new watchwords. The immediate task facing Schriever in early 1962 was responding vigorously to the McNamara-Rubel initiatives, which he saw as cost control measures. In a February 1962 memorandum, Schriever stated that cost overruns arose from ‘‘any one or a combination of’’ factors, including deliberate underestimation, adherence to overly strict standards, too much optimism in estimating performance and schedules, vacillation or changes in program direction, and inadequate military or contractor management.71

One area that Schriever had to improve was cost estimation. His comptroller’s office began by educating AFSC staff, instituting cost analysis training courses at the Air Force Institute of Technology in Dayton, Ohio. By February 1962, the first class of 25 students graduated from this course. AFSC also developed the Program Planning Report, which allowed for improved analysis of cost data with respect to technical and schedule progress. He also had AFSC adopt and modify the navy’s new planning tool, PERT.72

Schriever developed other ways to improve AFSC’s management capabilities. He established a Management Improvement Board, ‘‘made up of General Officers having the greatest experience in systems management matters ranging from funding, systems engineering, procurement and production, through research and development.’’ Schriever had board members examine ‘‘the entire area of systems management methods to include those of the Industrial complex as well as those of the Air Force.’’ He also reinstated the Air Force Industry Advisory Group, a Board of Visitors to improve working relationships with industry, and a program of ‘‘systems management program surveys.’’ AFSC also collected ‘‘lessons learned’’ information from programs and broadcast this information through publications and industry symposia. Schriever also used this information to produce management goals for AFSC.73

AFSC also communicated systems management concepts through education. Examples included a system program management course at the Air Force Institute of Technology and the creation of a systems management newsletter within AFSC. The Air Force Institute of Technology course used case studies taught by experienced program managers such as Col. Samuel Phillips of the Minuteman program. These program managers taught about program planning and budgeting, the McNamara reforms, organizational roles in system development, systems engineering, configuration management and testing, system acquisition regulations, program management techniques, contracting approaches, and financial methods.74

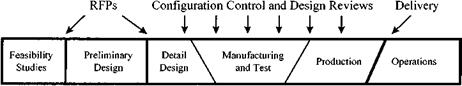

By the mid-1960s, the combination of AFSC management initiatives and the McNamara reforms produced a mature form of systems management that is still used in the aerospace industry today. Earlier concepts and practices of

|

Systems management phases. |

concurrency contributed the detailed planning and systems engineering coordination necessary to rapidly develop large-scale technologies. When ICBM failures became the primary concern, engineers added change control, quality control, and reliability to the mix. Finally, the cost concerns of the early 1960s — driven by rising ICBM costs, the Vietnam War, and social issues such as the civil rights movement—contributed phased planning and configuration management. Both new methods provided mechanisms to better predict costs.

McNamara, duly impressed with the procedures and reforms in Schriever’s organization, used them — modified to include phased planning for central control—as the basis for the DOD’s new regulations for the development of large-scale weapon systems. In 1965, the DOD enshrined phased planning and the systems concept as the cornerstone of its R&D regulations. Having already spread to NASA, these processes moved throughout the aerospace industry. Even when the processes were not explicitly used, industry accepted the assumptions and ideas encompassed in these regulations.75