To Touch the Face of God

And, while with silent lifting mind I’ve trod

The high untrespassed sanctity of space,

Put out my hand and touched the face of God.

—“High Flight,” Pilot Officer Gillespie Magee, No. 412

Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force,

died 11 December 1941

sts-5il

Crew: Commander Dick Scobee, Pilot Michael Smith, Mission Specialists Ellison Onizuka, Judy Resnik, and Ron McNair; Payload Specialists Christa McAuliffe and Gregory Jarvis Orbiter: Challenger Launched: 28 January 1986 Landed: N/A

Mission: Deployment of TDRS, astronomy research, Teacher in Space

Astronaut Dick Covey was the ascent CapCom for the 51L mission of the Space Shuttle Challenger. “There were two CapComs, the weather guy and the prime guy, and so it had been planned for some time that I’d be in the prime seat for [51L] and be the guy talking to them. . . . As the ascent CapCom you work so much with the crew that you have a lot of [connection]. In the training periods and stuff, not only do you sit over in the control center while they’re doing ascents and talk to them, but you also go and work with them on other things.”

Covey remembered getting together with the crew while the astronauts were in quarantine at jsc, before they flew down to Florida, to go over

|

31. Crew members of mission STS-51L stand in the White Room at Launchpad 39B. Left to right. Christa McAuliffe, Gregory Jarvis, Judy Resnik, Dick Scobee, Ronald McNair, Michael Smith, and Ellison Onizuka. Courtesy nasa. |

the mission one more time and work through any questions. “We got to go over and spend an hour or two in the crew quarters with them. I spent most of my time with Mike Smith and Ellison Onizuka, who was my longtime friend from test pilot school. They were excited, and they were raunchy, as you would expect, and we had a lot of fun and a lot of good laughs. It was neat to go do that. So that was the last time that I got to physically go and sit with the crew and talk about the mission and the ascent and what to expect there.”

On launch day the flight control team reported much earlier than the crew, monitoring the weather and getting ready for communication checks with the astronauts once they were strapped in. Covey said that he was excited to be working with Flight Director Jay Greene, whom he had worked with before, and that everything had seemed normal from his perspective leading into the launch. “From the control center standpoint,” Covey said, “I don’t remember anything that was unusual or extraordinary that we were working or talking about. It wasn’t something where we knew that someone was making a decision and how they were making that decision. We just flat didn’t have that insight. Didn’t know what was going on. Did not. It was pretty much just everything’s like a sim as we’re sitting there getting ready to go.”

Covey recalled that televisions had only recently been installed in the Mission Control Center and that the controllers weren’t entirely sure what they were supposed to make of them yet. “The idea [had been] you shouldn’t be looking at pictures; You should be looking at your data,” he said. “So that’s how we trained. Since the last time I’d been in the control center, they’d started putting [televisions in]. . . . I’d sat as the weather guy, and once the launch happens, I kind of look at the data, but I look over there at the Tv.”

Astronaut Fred Gregory was the weather CapCom for the 51L launch and recalled that nothing had seemed unusual leading up to the launch.

Up to liftoff, everything was normal. We had normal communication with the crew. We knew it was a little chilly, a little cold down there, but the ice team had gone out and surveyed and had not discovered anything that would have been a hazard to the vehicle. Liftoff was normal. . . . Behind the flight director was a monitor, and so I was watching the displays, but also every now and then look over and look at Jay Greene and then glance at the monitor. And I saw what appeared to be the solid rocket booster motor’s explosive devices—what I thought— blew the solid rocket boosters away from the tank, and I was really surprised, because I’d never seen it with such resolution before, clarity before. Then I suddenly realized that what I was intellectualizing was something that would occur about a minute later, and I realized that a terrible thing had just happened.

Covey said Gregory’s reaction was the first indication he had that something was wrong. “Fred is watching the video and sees the explosion, and he goes, ‘Wha—? What was that?’ Of course, I’m looking at my data, and the data freezes up pretty much. It just stopped. It was missing. So I look over and could not make heads or tails of what I was seeing, because I didn’t see it from a shuttle to a fireball. All I saw was a fireball. I had no idea what I was looking at. And Fred said, ‘It blew up,’ something like that.”

Covey recalled that the cameraman inside the control room continued to record what was happening there. “Amazingly, he’s still sitting there just cranking along in the control center while this was happening. Didn’t miss a beat,” he said, “because I’ve seen too many film footages of me looking in disbelief at this television monitor trying to figure out what the hell it was I was seeing.”

Off loop, Covey and Flight Director Jay Greene were talking, trying to gather information about what just happened. “There was a dialogue that started ensuing between Jay and myself,” Covey recalled, and Jay, he’s trying to get confirmation on anything from anybody, if they have any data, and what they think has happened, what the status of the or – biter is. All we could get is the solid rocket boosters are separated. Don’t know what else. I’m asking questions, because I want to tell the crew what to do. That’s what the ascent CapComs are trained to do, is tell them what to do. If we know something that they don’t, or we can figure it out faster, tell them so they can go and do whatever they need to do to recover or save themselves. There was not one piece of information that came forward; I was asking. I didn’t do it over the loop, so I did this between Jay and some of the other people that could hear, “Are we in a contingency abort? If so, what type of contingency abort? Can we confirm they’re off the SRBs?” Trying to see if there was anything I should say to the crew.

In all the confusion, he said, no one said anything about him attempting to contact the crew members, since no one knew what to tell them. “We didn’t have any comm. We knew that. That was pretty clear to me; so the only transmissions that I could have made would have been over a UHF [ultrahigh frequency], but if I didn’t have anything to say to them, why call them? So we went through that for several minutes, and so if you go and look at it, there was never a transmission that I made after ‘ Challenger, you’re go [at] throttle up.’ That was the last one, and there wasn’t another one.”

After a few minutes of trying to figure out if there was anything to tell the crew, reality started to hit. Covey said,

I remember Jay finally saying, “Okay, lock the doors. Everybody, no communications out. Lock the doors and go into our contingency modes of collecting data. ” I think when he did that, I finally realized; I went from being in this mode of, “What can we do? How do we figure out what we can do? What can we tell the crew? We’ve got to save them. We’ve got to help them save themselves. We’ve got to do something, ” to the realization that my friends had just died. … Of course, Fred and I were there together, which helped, because so many of the Challenger crew were our classmates, and so we were sharing that together. A special time that I’ll always remember being with Fred was there in the control center for that.

It was a confusing time for those in the Launch Control Center. The data being received was not real-time data, Gregory said; there was a slight delay. “I had seen the accident occur on the monitor. I was watching data come in, but I saw the data then freeze, but I still heard the commentary about a normal flight coming from the public affairs person, who then, seconds later, stopped talking. So there was just kind of stunned silence in Mission Control.”

“At this point,” Gregory said, “no one had realized that we had lost the orbiter. Many, I’m sure, thought that this thing was still flying and that we had just lost radio signals with it. I think all of these things were kind of running through our minds in the first five to ten seconds, and then everybody realized what was going on.”

What Covey and Gregory, relatively insular in their flight control duties, did not realize was that concerns over the launch had begun the day before. The launch had already been delayed six times, and because of the significance of the first Teacher in Space flight and other factors, many were particularly eager to see the mission take off. On the afternoon of 27 January (the nineteenth anniversary of the loss of astronauts Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee in the Apollo 1 pad fire), discussions began as to whether the launch should be delayed again. The launch complex at Kennedy Space Center was experiencing a cold spell atypical for the Florida coast, with temperatures on launch day expected to drop down into the low twenties Fahrenheit in the morning and still be near freezing at launch time.

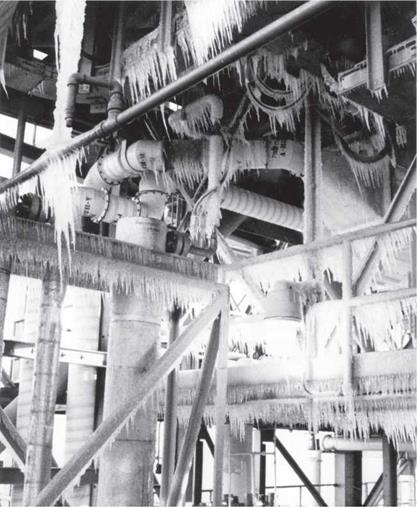

During the night, discussions were held about two major implications of the cold temperatures. The first was heavy ice buildup on the launch – pad and vehicle. The cold wind had combined with the supercooling of the cryogenic liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen in the external tank to lead to the formation of ice. Concerns were raised that the ice could come off during flight and damage the vehicle, particularly the thermal protection tiles on the orbiter. A team was assigned the task of assessing ice at the launch complex.

The second potential implication was more complicated. No shuttle had ever launched in temperatures below fifty degrees Fahrenheit before, and there were concerns about how the subfreezing temperatures would affect the vehicle, and in particular, the O-rings in the solid rocket boosters. The boosters each consisted of four solid-fuel segments in addition to the nose cone with the parachute recovery system and the motor nozzle. The segments were assembled with rubberlike O-rings sealing the joints between

|

32. On the day of Space Shuttle Challengers 28 January 1986 launch, icicles draped the launch complex at the Kennedy Space Center. Courtesy nasa. |

the segments. Each joint contained both a primary and a secondary O- ring for additional safety. Engineers were concerned that the cold temperatures would cause the O-rings to harden such that they would not fully seal the joints, allowing the hot gasses in the motor to erode them. Burn – through erosion had occurred on previous shuttle flights, and while it had never caused significant problems, engineers believed that there was potential for serious consequences.

During a teleconference held the afternoon before launch, srb contractor Morton Thiokol expressed concerns to officials at Marshall Space Flight Center and Kennedy Space Center about the situation. During a second teleconference later that evening, Marshall Space Flight Center officials challenged a Thiokol recommendation that nasa not launch a shuttle at temperatures below fifty-three degrees Fahrenheit. After a half-hour off-1 ine discussion, Thiokol reversed its recommendation and supported launch the next day. The three-hour teleconference ended after 11:00 p. m. (in Florida’s eastern time zone).

During discussions the next morning, after the crew was already aboard the vehicle, orbiter contractor Rockwell International expressed concern that the ice on the orbiter could come off during engine ignition and ricochet and damage the vehicle. The objection was speculation, since no launch had taken place in those conditions, and the NASA Mission Management Team voted to proceed with the launch. The accident investigation board later reported that the Mission Management Team members were informed of the concerns in such a way that they did not fully understand the recommendation.

Launch took place at 11:38 a. m. on 28 January. The three main engines ignited seconds earlier, at 11:37:53, and the solid rocket motors ignited at 11:38:00. In video of the launch, smoke can be seen coming from one of the aft joints of the starboard solid rocket booster at ignition. The primary O-ring failed to seal properly, and hot gasses burned through both the primary and secondary O-rings shortly after ignition. However, residue from burned propellant temporarily sealed the joint. Three seconds later, there was no longer smoke visible near the joint.

Launch continued normally for the next half minute, but at thirty-seven seconds after solid rocket motor ignition, the orbiter passed through an area of high wind shear, the strongest series of wind shear events recorded thus far in the shuttle program. The worst of the wind shear was encountered at fifty-eight seconds into the launch, right as the vehicle was nearing “Max Q,” the period of the highest launch pressures, when the combination of velocity and air resistance is at its maximum. Within a second, video captured a plume of flame coming from the starboard solid rocket booster in the joint where the smoke had been seen. It is believed that the wind shear broke the temporary seal, allowing the flame to escape. The plume rapidly became more intense, and internal pressure in the motor began dropping. The flame occurred in a location such that it quickly reached the external fuel tank.

The gas escaping from the solid rocket booster was at a temperature around six thousand degrees Fahrenheit, and it began burning through the exterior of the external tank and the strut attaching the solid rocket booster to the tank. At sixty-four seconds into the launch, the flame grew stronger, indicating that it had caused a leak in the external tank and was now burning liquid hydrogen escaping from the aft tank of the external tank. Approximately two seconds later, telemetry indicated decreasing pressure from the tank.

At this time, in the vehicle and in Mission Control, the launch still appeared to be proceeding normally. Having made it through Max Q, the vehicle throttled its engines back up. At sixty-eight seconds, Covey informed the crew it was “Go at throttle up.” Commander Dick Scobee responded, “Roger, go at throttle up,” the last communication from the vehicle.

Two seconds later, the flame had burned through the attachment strut connecting the starboard srb and the external tank. The upper end of the booster was swinging on its strut and impacted with the external tank, rupturing the liquid oxygen tank at the top of the external tank. An orange fireball appeared as the oxygen began leaking. At seventy-three seconds into the launch, the crew cabin recorder records Pilot Michael Smith on the intercom saying, “Uh-oh,” the last voice recording from Challenger.

While the fireball caused many to believe that the Space Shuttle had exploded, such was not the case. The rupture caused the external tank to lose structural integrity, and at the high velocity and pressure it was experiencing, it quickly began disintegrating. The two solid rocket boosters, still firing, disconnected from the shuttle stack and flew freely for another thirty – seven seconds. The orbiter, also now disconnected and knocked out of proper orientation by the disintegration of the external tank, began to be torn apart by the aerodynamic pressures. The orbiter rapidly broke apart over the ocean, with the crew cabin, one of the most solid parts of the vehicle, remaining largely intact until it made contact with the water.

All of that would eventually be revealed during the course of the accident investigation. At Mission Control, by the time the doors were opened again, much was still unknown, according to Covey.

[We] had no idea what had happened, other than this big explosion. We didn’t know if it was an srb that exploded. I mean, that was what we thought. We always thought SRBs would explode like that, not a big fireball from the external tank propellants coming together. So then that set off a period then of just trying to deal with that and the fact that we had a whole bunch of spouses and families that had lost loved ones and trying to figure out how to deal with that.

The families were in Florida, and I remember, of course, the first thing I wanted to do was go spend a little time with my family, and we did that. But then we knew the families were coming back from Florida and out to Ellington [Field, Houston], so a lot of us went out there to just be there when they came back in. I remember it was raining. Generally they were keeping them isolated, but a big crowd of us waiting for them, they loaded them up to come home. Then over the next several days most of the time we spent was trying to help the Onizukas in some way; being around. Helping them with their family as the families flew in and stuff like that.

After being in Mission Control for approximately twelve hours—half of that prior to launch and the rest in lockdown afterward, analyzing data, Gregory finally headed home.

The families had all been down at the Kennedy Space Center for the liftoff and they were coming back home. Dick Scobee, who was the commander, lived within a door or two of me. And when I got home, I actually preceded the families getting home; I remember that. They had the television remote facilities already set up outside of the Scobees’ house, and it was disturbing to me, and so I went over and, in fact, invited some of those [reporters] over to my house, and I just talked about absolutely nothing to get them away from the house, so that when June Scobee and the kids got back to the house, they wouldn’t have to go through this gauntlet.

The next few days, Gregory said, were spent protecting the crew’s families from prying eyes. “There was such a mess over there that Barbara and I took [Scobee’s] parents and just moved them into our house, and they must have stayed there for about four or five days. Then June Scobee, in fact, came over and stayed, and during that time is when she developed this concept for the Challenger Center. She always gives me credit for being the one who encouraged her to pursue it, but that’s not true. She was going to do it, and it was the right thing to do.”

Gregory recalled spending time with the Scobees and the Onizukas and the Smiths, particularly Mike Smith’s children. “It was a tough time,” he said.

It was a horrible time, because I had spent a lot of time with Christa McAuliffe and [her backup] Barbara Morgan, and the reason was because I had teachers in my family. On my father’s side, about four or five generations; on my mother’s side, a couple of generations. My mother was elementary school, and my dad was more in the high school. But Christa and I and Barbara talked about how important it was, what she was doing, and then what she was going to do on orbit and how it would be translated down to the kids, but then what she was going to do once she returned. So it was traumatic for me, because not only had I lost these longtime friends, with Judy Resnik and Onizuka and Ron McNair and Scobee, and then Mike Smith, who was a class behind us, but I had lost this link to education when we lost Christa.

Astronaut Sally Ride was on a commercial airliner, flying back to Houston, when the launch tragedy occurred. “It was the first launch that I hadn’t seen, either from inside the shuttle or from the Cape or live on television,” Ride recalled.

The pilot of the airline, who did not know that I was on the flight, made an announcement to the passengers, saying that there had been an accident on the Challenger. At the time, nobody knew whether the crew was okay; nobody knew what had happened. Thinking back on it, it’s unbelievable that the pilot made the announcement he made. It shows how profoundly the accident struck people. As soon as I heard, I pulled out my NASA badge and went up into the cockpit. They let me put on an extra pair of headsets to monitor the radio traffic to find out what had happened. We were only about a half hour outside of Houston; when we landed, I headed straight back to the Astronaut Office at jsc.

Payload Specialist Charlie Walker was returning home from a trip to San Diego, California, when the accident occurred.

I can remember having my bags packed and having the television on and searching for the station that was carrying the launch. As I remember it, all the stations had the launch on; it was the Teacher in Space mission. So I watched the launch, and to this day, and even back then I was still aggravated with news services that would cover a launch up until about thirty seconds, forty-five sec-

onds, maybe one minute in flight, after Max Q, and then most of them would just cut the coverage. “Well, the launch has been successful. ” [I would think,] “You don’t know what you’re talking about. You’re only thirty seconds into this thing, and the roughest part is yet to happen. ”

And whatever network I was watching ended their coverage. “Well, looks like we’ve had a successful launch of the first teacher in space. ” And they go off to the programming, and it wasn’t but what, ten seconds later, and I’m about to pick my bags up and just about to turn off the television and go out my room door when I hear, “We interrupt this program again to bring you this announcement. It looks like something has happened. ” I can remember seeing the long-range tracker cameras following debris falling into the ocean, and I can remember going to my knees at that point and saying some prayers for the crew. Because I can remember the news reporter saying, “Well, we don’t know what has happened at this point. ” I thought, “Well, you don’t know what has happened in detail, but anybody that knows anything about it can tell that it was not at all good. ”

Mike Mullane was undergoing payload training with the rest of the 62A crew at Los Alamos Labs in New Mexico. “We were in a facility that didn’t have easy access to a Tv,” said Mullane.

We knew they were launching, and we wanted to watch it, and somebody finally got a television or we finally got to a room and they were able to finagle a way to get the television to work, and we watched the launch, and they dropped it away within probably thirty seconds of the launch, and we then started to turn back to our training. Somebody said, “Well, let’s see if they’re covering it further on one of the other channels, ” and started flipping channels, and then flipped it to a channel and there was the explosion, and we knew right then that the crew was lost and that something terrible had happened.

Mullane theorized that someone must have inadvertently activated the vehicle destruction system or a malfunction caused the flight termination system to go off. “I was certain of it,” Mullane said.

I mean, the rocket was flying perfectly, and then it just blew up. It just looked like it had been blown up from this dynamite. Shows how poor you can be as a witness to something like this, because that had absolutely nothing to do with it.

But it was terrible. Judy was killed on it. She was a close friend. There were four people from our group that were killed. It was a terrible time. Really as bad as it gets. It was like a scab or a wound that just never had an opportunity to heal because you had that trauma.

Astronaut Mary Cleave recalled two very different sets of reactions to the tragedy from the people around her in the Astronaut Office. “For the guys in the corps, when you’re in the test pilot business, you’re sort of a tough guy,” she said.

It’s a part of the job. It’s a lousy part of the job, but it’s part of the job. But I mean, the secretaries and everybody else were really upset, so we spent some time with them. Before my first flight, I had signed up. I basically told my family, “Hey, I might not be coming back." When we flew, it was the heaviest payload to orbit. We were already having nozzle problems. I think a lot of us understood that the system was really getting pushed, but that’s what we’d signed up to do. I think probably a lot of people in the corps weren’t as surprised as a lot of other people were. I did crew family escort afterwards. I was assigned to help when the families came down, as an escort at jsc when the president came in to do the memorial service. Jim Buchli was in charge of the group; they put a marine in charge of the honor guard. So I got to learn to be an escort from a marine, which was interesting. I learned how to open up doors. This was sort of like it doesn’t matter if you’re a girl or boy, there’s a certain way people need to be treated when they’re escorted. So I did that. That was interesting. And it was nice to think that you could help at that point.

Charlie Bolden had just returned to Earth ten days earlier from his first spaceflight, 61c. His crew was wrapping up postmission debriefing, he recalled, and it gathered with others in the Astronaut Office to watch Challenger launch. “That was the end of my first flight, and we were in heaven. We were celebrating as much as anybody could celebrate,” he said. “We sat in the Astronaut Office, in the conference room with everybody else, to watch Challenger. Nobody was comfortable because of all the ice on the launchpad and everything. I don’t think there were many of us who felt we should be flying that day, but what the heck. Everybody said, ‘Let’s go fly.’ And so we went and flew.”

Bolden thought the explosion was a premature separation of the solid rocket boosters; he expected to see the vehicle fly out of the smoke and perform a return-to-launch-site abort. “We were looking for something good to come out of this, and nothing came out except these two solid rocket boosters going their own way.”

It took awhile, but it finally sunk in: the vehicle and the crew were lost. “We were just all stunned, just didn’t know what to do,” Bolden said. “By the end of the day we knew what had happened; we knew what had caused the accident. We didn’t know the details, but the launch photography showed us the puff of smoke coming out of the joint on the right – hand solid rocket booster. And the fact that they had argued about this the night before meant that there were people from [Morton] Thiokol who could say, ‘Let me tell you what happened. This is what we predicted would happen.’”

Bolden was the family escort for the family of 51L mission specialist Ronald McNair. Family escorts are chosen by crew members to be with the families during launch activities and to be a support to families if something happened to the crew, as was the case with 51L. Much of Bolden’s time in the year after the incident was spent helping the McNair family, which included Ron’s wife and two children. “I sort of became a surrogate, if you will, for [McNair’s children] Joy and Reggie, and just trying to make sure that Cheryl [McNair] had whatever she needed and got places when she was supposed to be there. Because for them it was an interminable amount of time, I mean years, that they went through the postflight grieving process and memorial services and that kind of stuff.”

Bolden’s 61c crewmate Pinky Nelson was on his way to Minneapolis, Minnesota, for the premier of the imax movie The Dream Is Alive, which included footage from Nelson’s earlier mission, 41c. Nelson recalled having worked closely with the 51L crew, which Nelson said would be using the same “rinky-dink little camera” as his crew to observe Halley’s Comet.

I’d spent a bunch of time trying to teach Ellison [Onizuka] how to find Halley’s Comet in the sky. [Dick] Scobee and I were really close friends because of 41C, so “Scobe” and I had talked a lot about his kind of a “zoo crew, ” about his crew and all their trials and tribulations. He really wanted to get this mission flown and over with. So I talked to them the night before, actually, from down at the Cape and wished them good luck and all that, and then the accident happened while I was on the airplane to Minneapolis.

Nelson flew back to Houston from Minneapolis that afternoon, arriving around the same time that the families were arriving from Florida. Nelson and his wife, Susie, and astronaut Ox van Hoften and his wife convened at the Scobees’ home.

“The national press was just god-awful,” Nelson said.

I’ve never forgiven some of those folks. . . . I mean, it’s their job, but still— for their just callous, nasty behavior. We just spent a lot of time just kind of over at Scobee’s, trying to just be there and help out. I still can’t drink flavored coffee. That’s the only kind of coffee June had, vanilla bean brew or something. So whenever I smell that stuff, that’s always my memory of that, is having bad coffee at Scobes house, trying to just get their family through the time, just making time pass. We had to unplug the phones. The press was parked out in front of the house. It was a pretty bad time for all that. We went over and tried to do what we could with some of the other families. My kids had been good friends with Onizuka’s kids; they’re the same age. Lorna [Onizuka] was having just a really hard time. Everyone was trying to help out where we could.

Memorial services were beginning to be held for the lost crew members even as the agency was continuing with its search for the cockpit and the bodies of the lost crew. “It was terrible, going to the memorial services,” admitted Mullane.

It was one of those things that didn’t seem to end, because then they were looking for the cockpit out there. I personally thought, “Why are we doing this? Leave the cockpit down there. What are you going to learn from it?" Because by then they knew the SRB was the problem. . . . I remember thinking, “Why are we even looking for that cockpit? Just bury them at sea. Leave them there."I’m glad they did, though, because later I heard it was really shallow where that cockpit was. It was like, I don’t know, like eighty feet or something, which is too shallow, because somebody eventually would have found it and pulled it up on a net or been diving on it or something. So it’s good that they did look for it. So you had these several weeks there, and then they bring that cockpit up, and then you have to repeat all the memorial services again, because now you have remains to bury. And then plus on top of that, you had the revelation that it wasn’t an accident; it was a colossal screwup. And you had that to deal with. So it was a miserable time, about as bad as I’ve ever lived in my life, were those months surrounding, months and years, really, surrounding the Challenger tragedy.

Astronaut Bryan O’Connor was at Kennedy Space Center during the debris recovery efforts and postrecovery analysis. O’Connor recalled being on the pier when representatives from the Range Safety Office at Cape Canaveral were trying to determine whether what happened was an inadvertent range safety destruct—if somehow there had been a malfunction of the destruct package intended to destroy the vehicle should a problem cause it to pose a safety risk to those on the ground. “I remember there was a Coast Guard cutter that came in and had some pieces and parts of the external tank,” O’Connor said. “On the second or third day, I think, one of these ships actually had a piece of the range safety destruct system from the external tank, intact for about halfway and then ripped up the other half of it. When he looked at that, he could tell that it hadn’t been a destruct.”

O’Connor had accident investigation training and was then assigned to work with Kennedy Space Center on setting up a place to reconstruct the vehicle as debris was recovered. “I remember we put tape down on the floor. We got a big room in the Logistics Center. They moved stuff out of the way. As time went on, the need increased for space, and we actually ended up putting some things outside the Logistics Center, like the main engines and some of the other things. But the orbiter pretty much was reassembled piece by piece over a period of time as the parts and pieces were salvaged out of the water, most of them floating debris, but some, I think, was picked up from subsurface.”

Recovery efforts started with just a few ships, O’Connor said, but grew into a large fleet. According to the official Rogers Commission Report on the accident, sixteen watercraft assisted in the recovery, including boats, submarines, and underwater robotic vehicles from NASA, the navy, and the air force. “It was one of the biggest salvage efforts ever, is what I heard at the time,” O’Connor said. “Over a period of time, we were able to rebuild quite a bit of the orbiter, laying it out on the floor and, in some cases, actually putting it in a vertical structure. Like the forward fuselage, for example, we tried to make a three-dimensional model from the pieces that we recovered there.”

While the goal had originally been to determine the cause of the accident, the investigation eventually shifted to its effects, with analysis of the

|

33- This photograph, taken a few seconds after the loss of Challenger, shows the Space Shuttle’s main engines and solid rocket booster exhaust plumes entwined around a ball of gas from the external tank. Courtesy nasa. |

debris revealing how the various parts of the vehicle had been affected by the pressures during its disintegration.

Astronaut Joe Kerwin, a medical doctor before his selection to the corps and a member of the first crew of the Skylab space station, was the director of Space Life Sciences at Johnson Space Center at the time of the accident. “Like everybody else at jsc I remember exactly where I was when it happened,” Kerwin recalled.

I didn’t see it live. In fact, I was having a staff meeting in my office at jsc and we had a monitor in the background because the launch was taking place. And I just remember all of us sort of looking up and seeing this explosion taking place on the monitor. And there was the moment of silence as each of us tried to absorb what it looked like was or might be going on, and then sort of saying, “Okay, guys, I think we better get to work. We’re going to need to coordinate with the Astronaut Office. We’re going to have to have flight surgeons. Sam, you contact the doctors on duty down at the

Cape and make sure that they have the families covered,” and we just sort of set off like that.

His medical team’s first actions were simply to take care of the families of the crew members, Kerwin said. “Then as the days went by and the search for the parts of the orbiter was underway I went down to Florida and coordinated a plan for receiving bodies and doing autopsies and things of that nature. It included getting the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology to commit to send a couple of experts down if and when we found remains to see whether they could determine the cause of death.”

But the crew compartment wasn’t found immediately and Kerwin went back home to Houston, where days turned into weeks.

I was beginning to almost hope that we wouldn’t have to go through that excruciating investigation when I had a call from Bob Crippen that said, no, we’ve found the crew compartment and even at this late date there are going to be some remains so how about let’s get down here. I went down immediately.

By that time the public and press response to the accident and to NASA had turned bad, and NASA, which had always been considered one of the best organizations in government, was now one of the worst organizations in government and there was a lot of bad press and there were a lot of paparazzi there in Florida who just wanted to get in on the action and get gruesome pictures or details or whatever they could. So we had to face that.

In addition to dealing with the press, Kerwin said recovery efforts also had to deal with local politics.

The local coroner was making noises like this accident had occurred in his jurisdiction and therefore he wanted to take charge of any remains and perform the autopsies himself, which would have been a complicating factor, to say the least. I didn’t have to deal with that, I just knew about it and that I might have had to deal with [the] coroner if the offensive line didn’t block him. But the higher officials in NASA and in particular in the State of Florida got him called off saying, “No, this accident was in a federal spacecraft and it occurred offshore and you just back off”

By the time Kerwin arrived at the scene, the recovery team had come up with several different possible ways to get the remains to where they would be autopsied.

In view of the lateness of the time and in view of the press coverage and all that stuff, we decided that we needed a much more secure location for this activity to take place and we were given space in one of the hangars at Cape Canaveral, one of the hangars in which the Mercury crews trained way back in the early sixties. We quickly prepared that space for the conduct of autopsies. When the remains were brought in they were brought into one of the piers by motorized boat. It was done after dark, and there was always one or two or three astronauts with the remains and we put up a little screen because right across the sound from this pier the press had set up floodlights and cameras and bleachers.

An unmarked vehicle was used to transport the remains to the hangar, while a nasa ambulance was used as a decoy to keep the location of the autopsies a secret. “We knew by that time, and really knew from the beginning, that crew actions or lack of actions didn’t have anything to do with the cause of the Challenger accident,” Kerwin said.

As an accident investigator you ask yourself that first—could this have been pilot error involved in any way, and the immediate answer was no. But we still needed to do our best to determine the cause of death, partly because of public interest but largely because of family interest in knowing when and under what circumstances their loved ones died. So that was the focus of the investigation.

The sort of fragmentary remains that were brought in, having been in the water for about six weeks, gave us no clue as to whether the cause of death was ocean impact or whether it could’ve taken place earlier. So the only thing left for the autopsies was to determine, was to prove, that each of the crew members had had remains recovered that could identify that, yes, that crew member died in that accident. That was not easy but we were able to do it. So at the end of the whole thing I was able to send a confidential letter to the next ofkin of each of the crew members stating that and stating what body parts had been recovered, a very, very short letter.

In addition to identifying the remains, Kerwin and his team worked to identify the exact cause of death of the crew members.

We’d all seen the breakup on television, we knew it was catastrophic, and my first impression as a doctor was that it probably killed all the crew just right at the time of the explosion. But as soon as they began to analyze the camera footage, plus what very little telemetry they had, it became apparent that the g-forces were not that high, not as high as you’d think. I guess the crew compartment was first flung upward and away from the exploding external tank and then rapidly decelerated by atmospheric pressure until it reached free fall. The explosion took place somewhere about forty thousand feet, I think about forty-six or forty-seven thousand, and the forces at breakup were estimated to be between fifteen and twenty gs, which is survivable, particularly if the crew is strapped in properly and so forth. The crew compartment then was in free fall, but upward. It peaked at about sixty-five thousand feet, and about two and half minutes after breakup hit the ocean at a very high rate of speed. If the crew hadn’t died before, they certainly died then.

Kerwin said he and his team then worked to refine their understanding of exactly what had happened when. “Our investigation attempted to determine whether or not the crew compartment’s pressure integrity was breeched by the separation, and if so, if the crew compartment had lost pressure, we could then postulate that the crew had become profoundly unconscious because the time above forty thousand feet was long enough and the portable emergency airpack was just that, it was an airpack, not an oxygen pack, so they had no oxygen available. They would have become unconscious in a matter of thirty seconds or less depending on the rate of the depressurization and they would have remained unconscious at impact.”

But the damage to the compartment was too great to allow Kerwin to determine with certainty whether the cabin had lost pressure. He said that, given what it would mean for the crew’s awareness of its fate, his team was almost hopeful of finding evidence that the crew compartment had been breached, but they were unable to make a conclusive determination.

The damage done to the crew compartment at water impact was so great that despite a really lot of effort, most of it pretty expert, to determine whether there was a pressure broach in any of the walls, in any of the feed-throughs, any of the windows, any of the weak points where you might expect it, we couldn’t rule it out but we couldn’t demonstrate it either. We lifted all the equipment to see whether any of the stuff in the crew compartment looked as if it had been damaged by rapid decompression, looked at toothpaste tubes and things like that, tested some of them or similar items in vacuum chambers to determine whether that sort of damage was pressure-caused and that was another blind hole. We simply could not determine. And then as to the remains, in a case of immediate return of the remains we might have gotten lucky and been able to measure tissue oxygen concentration and tissue carbon dioxide concentration and gotten a clue from that but this was way too late for that kind of thing.

Finally, after all ofthat we had to just, I just had to sit down and write the letter to Admiral [Richard H.] Truly stating that we did not know the cause of death.

Sally Ride was named to the commission that was appointed to investigate the causes of the accident. President Reagan appointed former secretary of state William Rogers to head a board to determine the factors that had resulted in the loss of Challenger. (Ride has the distinction of being the only person to serve on the presidential commission investigations of both the Challenger and the Columbia accidents.) Ride was in training at the time of the accident and was assigned to the presidential commission within just a few days of the accident. The investigation lasted six months.

“The panel, by and large, functioned as a unit,” Ride recalled.

We held hearings; we jointly decided what we should look into, what witnesses should be called before the panel, and where the hearings should be held. We had a large staff so that we could do our own investigative work and conduct our own interviews. The commission worked extensively with the staff throughout the investigation. There was also a large apparatus put in place at NASA to help with the investigation: to analyze data, to look at telemetry, to look through the photographic record, and sift through several years of engineering records. There was a lot of work being done at NASA under our direction that was then brought forward to the panel. I participated in all ofthat. I also chaired a subcommittee on operations that looked into some of the other aspects of the shuttle flights, like was the astronaut training adequate? But most of our time was spent on uncovering the root cause of the accident and the associated organizational and cultural factors that contributed to the accident.

Ride said she had planned to leave nasa after her upcoming third flight and do research in an academic setting. But her role in the accident investigation caused her to change her plans. “I decided to stay at nasa for an extra year, simply because it was a bad time to leave,” explained Ride.

She described that additional year as one that was very difficult both for her personally and for the corps. “It was a difficult time for me and a difficult time for all the other astronauts, for all the reasons that you might expect,” said Ride. “I didn’t really think about it at the time. I was just going from day to day and just grinding through all the data that we had to grind through. It was very, very hard on all of us. You could see it in our faces in the months that followed the accident. Because I was on the commission, I was on Tv relatively frequently. They televised our hearings and our visits to the NASA centers. I looked tired and just kind of gray in the face throughout the months following the accident.”

Astronaut Steve Hawley, who was married to Ride at the time, recalled providing support to the Rogers Commission, particularly in putting together the commission’s report, Leadership and America’s Future in Space.

The chairman felt that it was appropriate to look not only at the specifics of that accident but other things that his group might want to say about safety in the program, and that included, among other things, the role of astronauts in the program, and that was one of the places where I think I contributed, was how astronauts ought to be involved in the program. I remember one of the recommendations of the committee talked about elevating the position of director of FCOD [Flight Crew Operations Directorate], because at the time of the Challenger accident, he was not a direct report to the center director. That had been a change that had been made sometime earlier, I don’t remember exactly when. And that commission felt that the guy that was head of the organization with the astronauts should be a direct report to the center director. So several people went back to Houston and put George [Abbey] s desk up on blocks in an attempt to elevate his position. I think he left it there for some period of time, as far as I can remember.

Though not everyone in the Astronaut Office was involved in the Rogers Commission investigation and report, many astronauts were involved in looking into potential problems in the shuttle hardware and program. Recalled O’Connor,

I remember that a few days after the accident Dick Truly and the acting administrator [William Graham] were down at ksc. Again, because I had accident investigation training, they had a discussion about what’s the next steps

here. The acting administrator, it turned out, was very reluctant to put a board together, a formal board. We had an Accident Investigation Team that was assembling; eventually became under the cognizance of J. R. Thompson. We had a bunch of subteams under him, and then he was reporting to Dick Truly. But we never called out a formal board, and I think there was more or less a political feel that this is such high visibility that we know for sure that the Congress or the president or both are going to want to have some sort of independent investigation here, so let’s not make it look like we’re trying to investigate our own mishap here. And that’s why he decided not to do what our policy said, which is to create a board. We stopped short of that.

Once the presidential commission was in place, O’Connor said it was obvious to Dick Truly that he needed to provide a good interface between the commission and nasa. Truly assigned O’Connor to set up an “action center” in Washington DC for that purpose. The center kept track of all the requests from the commission and the status of the requests.

“They created a room for me, cleared out all the desks and so on,” O’Connor recalled. “We put [up] a bunch of status boards; very old-fashioned by today’s standard, when I think about it. It was more like World War Il’s technology. We had chalkboards. We had a paper tracking system, an IBM typewriter in there, and so on. It all seemed so ancient by today’s standards, virtually nothing electronic. But it was a tracking system for all the requests that the board had. It was a place where people could come and see what the status of the investigation was.”

The center became data central for nasa’s role in the investigation. In addition to the data keeping done there, Thompson would have daily teleconferences with all of his team members to find out what was going on.

Everybody would report in, what they had done, where they were, where they were on the fault tree analysis that we were doing to x out various potential cause factors. I remember the action center became more than just a place where we coordinated between NASA and the blue-ribbon panel. It was also a place where people could come from the [Capitol] Hill or the White House. We had quite a few visitors that came, and Dick Truly would bring them down to the action center to show them where we were in the investigation. So it had to kind of take on that role, too, of publicly accessible communication device.

I did that job for some weeks, and then we rotated people. [Truly] asked that George Abbey continue [to provide astronauts]. George had people available now that we’re not going to fly anytime soon, so he offered a bunch of high-quality people. . . . So shortly after I was relieved from that, I basically got out of the investigation role and into the “what are we going to do about it" role and was assigned by George to the Shuttle Program Office.

As board results came out, changes began to be made. For example, O’Connor said, all of the mission manifests from before the accident were officially scrapped.

I was relieved of my job on a crew right away. I think they called it 6im, which was a mission I was assigned to right after I got back from 6ib. I cant remember who all the members were, but my office mate, Sally Ride, and I were both assigned to that same mission, 6im. Of course, when the accident happened, all that stuffbecame questionable and we stopped training altogether. I don’t think that mission ever resurrected. It may have with some other name or number, but the crew was totally redone later, and the two of us got other assignments.

In the meantime, O’Connor was appointed to serve as the assistant program manager for operations and safety. His job included coordinating how NASA was going to respond to a couple of the major recommendations that came out of the blue-ribbon panel. The panel had ten recommendations, covering a variety of subjects. One of them had to do with how to restructure and organize the safety program at NASA. Another one O’Connor was involved with dealt with wheels, tires, brakes, and nose-wheel steering.

“It was all the landing systems,” he explained.

Now, that may sound strange, because that had nothing to do with this accident, but the Challenger blue-ribbon panel saw that, as they were looking at our history on shuttle, they saw that one of the bigger problems we were addressing technically with that vehicle was landing rollout. We had a series of cases where we had broken up the brakes on rollout by overheating them or overstressing them. We had some concerns about automatic landings. We had some concerns about steering on the runway in cases of a blown tire or something like that. So they chose to recommend that we do something about these things, put more emphasis on it, make some changes and upgrades in that area.

In the wake of the accident, even relatively low-profile aspects of the shuttle program were reexamined and reevaluated. “nasa wanted to go back and look at everything, not just the solid rocket boosters, but everything, to determine, is there another Challenger awaiting us in some other system,” recalled Mullane, who was assigned to review the range safety flight termination system, which would destroy the vehicle in the event it endangered lives. “I always felt it was a moral issue on this dynamite system. I always felt it was necessary to have that on there, because your wives and your family, your Lcc [Launch Control Center] people are sitting there two and a half miles away. If you die, that’s one thing. But if in the process of you dying that rocket lands on the LCC and kills a couple of hundred people, that’s not right. So they should have dynamite aboard it to blow it up in case it is threatening the civilian population.”

While Mullane himself supported having the flight termination system on the vehicles, he said that some of his superiors did not.

I could not go to the meetings and present their position. I couldn’t. I mean, to me it was immoral. It was immoral to sit there and say we fly without a dynamite system aboard. That’s immoral. And we threatened lcc, we threaten our families, we threaten other people. We’re signing up for the risk to ride in the rocket.

That was another bad time of my life, because I took a position that was counter to my superiors’ position, and I felt that it was jeopardizing my future at nasa. I didn’t like that at all, didn’t like the idea that I was supposed to just parrot somebody’s opinion and mine didn’t count on that issue. . . . So I did not like that time of my life at all. I had an astronaut come to me once. . . who heard my name being kicked around as a person that was causing some problems. And that’s the last thing you want in your career is to hear that your name is in front of people who make launch crew decisions, who make crew decisions, and basically, it looks like I’m a bad apple. But I just couldn’t do it. . . . I said, “You go. You do it. I cant. It’s immoral." By the way, the end of that is that the solid boosters retained their dynamite system aboard. It was taken off the gas tank, making it much safer, at least now two minutes up when the boosters are gone, we don’t have to dynamite aboard anymore, so it could fail and blow you up. But that’s the right decision right there. You protect the civilians, you protect your family, you protect lcc with that system.

The results from the commission questioned the NASA culture, and according to Covey some within the agency found that hard to deal with, especially while still recovering from the loss of the crew and vehicle. “Everybody was reacting basically to two things,” Covey said. “One was the fact that they had lost a Space Shuttle and lost a crew, and two, the Rogers Commission was extremely critical, and in many cases, rightfully so, about the way the decision-making processes had evolved and the culture had evolved.”

Covey noted,

Those two things together are hard for any institution to accept, because this was still a largely predominant workforce that had come through the Apollo era into the shuttle era and had been immensely successful in dealing with the issues that had come through both those programs to that point. So to be told that the culture was broken was hard to deal with, and that’s because culture doesn’t change overnight, and there was a lot of people that didn’t believe that that was an accurate depiction of the situation and environment that existed within the agency, particularly at the Johnson Space Center.

Personnel changes began to take place, including the departures of George Abbey, the long-time director of flight crew operations, and John Young, chief of the Astronaut Office. “We started seeing a lot of personnel changes in that time period in leadership positions,” Covey said.

I think they were a matter oftiming and other things, but George Abbey had been the director of flight crew operations for a long time, and somewhere in there George left that position. Don Puddy came in as the director of flight crew operations, and that sat poorly with a lot of people, because he wasn’t out of Flight Crew Operations; he was a flight director. So that was something that a lot of people just had a hard time accepting. John Young left from being chief of the Astronaut Office, and Dan Brandenstein came into that position. I’m trying to remember what happened in Mission Operations, but somewhere in there Gene Kranz left; I cant remember when, and I’m not sure when in that spectrum of things that he did. So there were changes there. The center director changed immediately after the Challenger accident, also, and changes were rampant at headquarters. So, basically, there was a restructuring of the leadership team from the administrator on down.

In time, the astronaut corps grieved and adjusted to leadership changes, and their focus returned to flying. “As jsc does,” Covey said, “once they got past the grief and got past the disappointment of failure and acceptance of their role relative to the decision-making process, they jumped in and said, ‘Okay, our job is flying. Let’s go figure out how we’re going to fly again.’”

Covey said the Challenger accident caused some in the astronaut corps to be wary of the NASA leadership structure and to distrust that the system would make the right kinds of decisions to protect them. “I wouldn’t say it was a bunker mentality, but it was close to that,” Covey said.

The idea that, as it played out, that there were decisions made and information that may not have been fully considered, and as you can see from all of it, a relatively limited involvement of any astronauts or flight crew people in the decision that led up to the launch; very little, if any. So that led to some changes that have evolved over time where there are more and more astronauts that have been involved in that decision-making process at the highest levels, either within the Space Shuttle program or in the related activities, where before it was like, “Yeah, those guys will make the right decision, and we’ll go fly."

Along those same lines, Fred Gregory commented that the tragedy was a moment of realization for many about the dangers of spaceflight.

The first four missions we called test flights, and then on the fifth mission we declared ourselves operational. We were thinking offlying journalists, and we had Pete Aldridge, who was the secretary of the air force. [about to fly]. I mean, we were thinking of ourselves as almost like an airline at that point. It came back safely. Everything was okay, even though there may have been multiple failures or things that had degraded. When we looked back, we saw that, in fact, we had had this erosion of those primary and secondary O-rings, but since it was a successful mission and we came back, it was dismissed almost summarily. I think there was a realization that we were vulnerable, and that this was not an airliner, flying to space was risky, and that we were going to have to change the approach that we had taken in the past.

During the investigation, new light was shined on past safety issues and close calls. Astronaut Don Lind recalled being informed of a situation that occurred on his 51B mission, less than a year earlier.

What happened was that Bob Overmyer and I had shared an office for three and a half years, getting ready for this mission. Bob, when they first started the

Challenger investigation, was the senior astronaut on the investigation team. He came back from the Cape one day, walked in the office, slumped down in the chair, and said, “Don, shut the door." Now, in the Astronaut Office, if you shut the door, it’s a big deal, because we tried to keep an open office so people could wander in and share ideas. . . . So I shut the door, and Bob said, “The board today found out that on our flight nine months previously we almost had the same explosion. We had the same problems with the O-rings on one of our boosters." We talked about that for a few minutes, and he said, “The board thinks we came within fifteen seconds of an explosion. ”

After learning this, Lind traveled out to what was then Morton Thio – kol’s solid rocket booster facility in Utah to find out exactly what had happened on his flight.

Alan McDonald, who was the head of the Booster Division, sat down with me. . . . He got out his original briefing notes for Congress, which I now have, and outlined exactly what had happened. There are three separate O-rings to seal the big long tubes with the gases flowing down through them at about five thousand degrees and 120 psi. The first two seals on our flight had been totally destroyed, and the third seal had 24 percent of its diameter burned away. McDonald said, “All of that destruction happened in six hundred milliseconds, and what was left of that last O-ring if it had not sealed the crack and stopped that outflow of gases, if it had not done that in the next two hundred to three hundred milliseconds, it would have been gone all the way. You’d never have stopped it, and you’d have exploded. So you didn’t come within fifteen seconds of dying, you came within three-tenths of one second of dying. " That was thought provoking.

In the wake of the Challenger disaster, all future missions were scrubbed and the flight manifest was replanned. Some missions were rescheduled with new numbers and only minor changes, while other planned missions and payloads were canceled entirely.

Recalled Charlie Walker of the electrophoresis research he had been conducting, “The opportunity just went away with the national policy changes; commercial was fourth priority, if it was a priority at all, for shuttle manifest. . . . Shuttle would not be flying with the regularity or the frequency that had been expected before.”

The plans to use the Centaur upper stage to launch the Ulysses and Galileo spacecraft from the shuttle were also canceled as a result of the accident. Astronaut Mike Lounge had been assigned to the Ulysses Centaur flight, which was to have flown in spring 1986 on Challenger. “So when we saw Challenger explode on January 28, before that lifted off, I remember thinking, ‘Well, Scobee, take care of that spaceship, because we need it in a couple of months.’ We would have been on the next flight of Challenger"

Lounge recalled that his crew was involved in planning for the mission during the Challenger launch. They took a break from discussing the risky Centaur mission, including ways to eject the booster if necessary, so that they could watch the 51L launch on a monitor in the meeting room. Lounge said the disaster shone a new light on the discussions they’d been having. “We assumed we could solve all these problems. We were still basically bulletproof. Until Challenger, we just thought we were bulletproof and the things would always work.”

Rick Hauck, who was assigned to command the Ulysses Centaur mission, was glad to see the mission canceled. “Would it have gotten to the point where I would have stood up and said, ‘This is too unsafe. I’m not going to do it’?” Hauck said. “I don’t know. But we were certainly approaching levels of risk that I had not seen before.”

For Bob Crippen, the Challenger accident would result in another loss, that of his final opportunity for a shuttle flight. The ramifications of the accident meant that he ended his career as a flight-status astronaut the same way he began it—in the crew quarters for Vandenberg’s SLC-6 launch complex, waiting for a launch that would never come. In the 1960s that launch had been of the Air Force’s Manned Orbiting Laboratory. In 1986 it was shuttle mission 62A.

“If I have one flying regret in my life, it was that I never had an opportunity to do that Vandenberg mission,” Crippen said.

We [had been] going to use filament-wound solid rockets, whereas the solid rockets that we fly on board the shuttle have steel cases. That was one of the things, I think, that made a lot of people nervous. . . . We needed the filament-wounds to get the performance, the thrust-to-weight ratio that we needed flying out of Vandenberg. So they used the filament-wound to take the weight out. After we had the joint problem on the solids with Challenger; most people just couldn’t get comfortable with the filament-wound case, so that was one of the aspects of why they ended up canceling it.

As the agency, along with the nation, was reevaluating what the future of human spaceflight would look like, what things should be continued, and what things should be canceled, the astronauts in the corps had to make the same sorts of decisions themselves. Many decided that the years-long gap in flights offered a good time to leave to pursue other interests, but many stayed on to continue flying.

“I think it was a very sobering time,” Jerry Ross said. “I mean, we always knew that that was a possibility, that we would have such a catastrophic accident. I think there was a lot of frustration that we found out fairly soon afterwards that the finger was being pointed at the joint design and, in fact, that there had been quite a bit of evidence prior to the accident that that joint design was not totally satisfactory. Most of us had never heard that. We were very shocked, disappointed, mad.”

Several astronauts left the office relatively soon after the accident, Ross said, and a stream of others continued to leave for a while afterward. “There were more people that left for various different reasons; some of them for frustration, some of them knowing that the preparations for flight were going to take longer, some of them responding to spouses’ dictates or requests that they leave the program now that they’d actually had an accident.”

Ross discussed his future at NASA with his family and admitted to having some uncertainty at first as to what he wanted to do.

I had mixed feelings at first about wanting to continue to take the risk of flying in space, but at the same time, all of the NASA crew members on the shuttle were good friends of mine, and I felt that if I were to quit and everybody else were to quit, then they would have lost their lives for no good benefit or progress. If you reflect back on history, any great undertaking has had losses; you know, wagon trains going across the plains or ships coming across the ocean. I was just watching a TV show that said in the 1800s, one out of every six ships that went across. . . the ocean from Europe to here didn’t make it. So there’s risk involved in any type of new endeavor that’s going on. And I got into the program with my eyes wide open, both for the excitement and the adventure of it, but also I felt very strongly that it was important that we do those kinds of things for the future of mankind and for the good of America.

After getting through the shock and getting through the memorial services and all that, even though I was frustrated I wasn’t getting a whole lot to do to help with the recovery effort, I was very determined that I was not going to leave, after talking with the family and getting their agreement, and that I was going to do whatever I could to help us get back to flying as soon as we could and to do it safer.