Open for Business

The demonstration missions were complete. The shuttle was considered operational. America’s new Space Transportation System was open for business, and one of its primary purposes would be the deployment of satellites.

sTs-5

Crew: Commander Vance Brand, Pilot Bob Overmyer, Mission Specialists Joe Allen and Bill Lenoir Orbiter: Columbia Launched: 11 November 1982 Landed: 16 November 1982 Mission: Launch of two communications satellites

Satellite deployment was precisely the mission of the first operational mission, sts-5. It was the first shuttle flight to deploy satellites into geosynchronous orbit, which is ideal for communications satellites because the satellite remains at roughly the same longitude as it orbits Earth. To achieve a geosynchronous orbit, a satellite must reach an altitude around one hundred times higher than that at which the shuttle orbits. For the shuttle to launch such a satellite, the satellite was carried into low Earth orbit in the shuttle’s payload pay and then boosted into the higher orbit using a booster rocket.

sts-5 was a mission full of firsts. In addition to the satellite deployments, sts-5’s four-man crew doubled the crew from the previous missions’ commander and pilot team to include the first two mission specialists to fly, Joe Allen and Bill Lenoir. Because of the deployments, STS-5 was also NASA’s first “commercial mission,” with the focus being on performing a service for paying customers.

Joe Allen had been selected as part of NASA’s second group of scientist – astronauts in 1967, and the move to larger crews had long been awaited by him

and his classmates. “The first assignment of mission specialists we knew was going to be [sts-]5, because the system was going to be declared operational after the first four test flights if nothing untoward happened,” Allen recalled.

We also knew that the next in line to be assigned were the scientists-astronauts. Those who had arrived [in the first of the two scientist-astronaut selections] had already flown, Jack Schmitt being the first to fly on the last Apollo, and then Joe Kerwin, Ed Gibson, and Owen K. Garriott had flown on the Skylab. So there were just now, I think, nine of us who would be considered. I guess I never thought much about it, but I almost assumed that maybe they went alphabetically, because they put myself and Bill Lenoir aboard that first operational flight. And I was thrilled, absolutely thrilled.

After having been assigned to the crew for just a few weeks, Allen decided he understood why he had been picked to be a part of that particular team, and he commented on it to George Abbey, who made crew assignments. “I was the impedance matching device between the two marine pilots and the mit engineer. ‘Impedance matching’ is an engineering term for getting very unlike electrical circuits to communicate, one with the other.”

Allen recalled that while he made the comment somewhat in jest, Abbey did not find it as amusing as he did. “I suspect that there were elements of truth in this, because I was very good at getting different groups of people to understand each other. With no scintilla of modesty at all, I would say that’s probably my strongest suit, understanding the way different individuals think about things and then enabling communication between them, in spite of their differences. I assert I was—I hope it’s not overblown—very successful in getting scientists to understand what flight-crew members needed, and getting flight-crew members to understand what scientists needed, even though neither group spoke the other’s language.”

Both groups had the same motivation—a successful mission—but each approached the task in its own way. “You wanted the ultimate result to be a successful mission, and successful in later Space Shuttle flights and in the last Apollo flights meant scientifically rich in what was achieved. So I was the impedance matching device between Bill Lenoir, an extremely smart, very well disciplined, very tightly wound individual, and Vance Brand and Bob Overmyer, whose backgrounds were military, with a military way of thinking about things, and they had a much higher tolerance for people being not quite so intense.”

The addition of mission specialists, and the corresponding increase in crew size, resulted in a modification to the orbiter for this flight. Prior to the mission, the commander’s and pilot’s ejection seats were pinned to prevent them from being able to be used. In Space Shuttle “Columbia”: Her Missions and Crews, Ben Evans wrote that the crew cabin was not large enough to have ejection seats for every member of the crew, only the commander and pilot. The thought with STS-5 was that if all of the crew wouldn’t be able to eject in the event of a problem during launch, none of the crew should be able to do so. Allen recalled that he and Lenoir were opposed to the pinning, arguing that it would be better for two astronauts to survive than for none to, but Brand disagreed. “He said, ‘That’s not a choice.’ He later said to me, ‘Joe, this is not a selfless decision on my part; indeed, . . . it’s selfish, because I could not live the rest of my life knowing that I survived and you didn’t. I couldn’t do it. I don’t think Bob could either. . . . I have some historical evidence as to that being a true statement. I don’t just surmise it.’” Allen explained that Brand had been a test pilot in England for a while, and some of the English bombers enabled the pilots to get out, but not the gunners, so there was a small body of data from psychological studies done on individuals who had escaped but, in escaping, had left their shipmates to a certain death. “They had been definitely tormented, in terms of what the data showed, for the rest of their lives. So it was not a good solution. Vance was aware of that data, and he didn’t want to be another bit of statistic in that database—a decision I thought was gracious. He said it was selfish; I didn’t think it was selfish at all.”

When launch day finally arrived, STS-5 added to its list of firsts by becoming the first shuttle mission to launch right on time. “We didn’t have one hiccup, not one delay, no nothing, and we went. . . on time,” recalled Allen. “We were told the night before that a Russian spaceship had actually changed the timing of its orbit somewhat and would come right over the Cape at exactly that time. Because we did launch on time, I suspect there are some photographs that could be found in the archives of the Soviets of us coming off the ground. I have no idea, but clearly they intended to at least watch us do it with their own eyes.”

On the day before launch, however, Leonid Brezhnev, the premier of Russia, died, and newspapers around the world were filled with news of his death, not of the Americans’ space launch. “There was maybe a little blurb, a little photo of us in the lower corner of some newspapers, but we were pretty much second-page news, with the exception of my hometown, Crawfordsville, Indiana, where I was the front page,” Allen said.

That hometown front page was a major step forward for Allen. Years earlier, in August 1967, when he was selected as an astronaut, this same hometown newspaper ran a front-page account of the calf-judging contest at the county fair, with only a small article on the back page about the local native selected to be a nasa astronaut. “My mother knew the newspaper editor very well, and she called him, quite upset,” Allen recalled. “She said to him, ‘Harold, you know my son Joe was selected as an astronaut. I think that’s very important news, and there’s practically nothing.’ And he said to her, ‘Harriet, you know perfectly well we’re a small town; we’re a very small newspaper. If you want a story about your son Joe in the paper, you’re going to have to write it yourself.’” By the time he actually flew into space, however, Allen merited front-page news without his mother having to write it.

The first priority of STS-5 was to successfully deploy the first hardware put into orbit by the Space Shuttle. Two commercial communications satellites were deployed, one for Canada and one for Satellite Business Systems. Allen said the crew worked closely with the satellite developers to understand how the satellites were put together and what was needed for successful deployment. “The concept of the satellite in itself is simple,” Allen explained.

They are meant to be deployed spinning, and the way you do it is just put the satellite on a table that will spin, like you put a record onto a record player. .. . It’s mounted on the table prior to launch, then you go to orbit. . . . Once there, you cause the table to spin and you point the shuttle in exactly the right direction, and then at precisely the right part of the orbit, you just release hold-down arms that are holding the satellite to the tabletop. When you release the arms, springs on which the satellite sits expand and just give it a very gentle push out, spinning very beautifully.

The second-highest-priority planned objective of STS-5 was the Space Shuttle’s first extravehicular activity, by Allen and Bill Lenoir. “Although we had other bits and pieces of experiments to do,” Allen recalled, “on the day before the spacewalk was to take place, we commented to ourselves that we really had just two important things left to do. One was the spacewalk

and then the second was the reentry and a safe landing. I made the observation, ‘Vance, out of these two, if we have to make a choice, let’s choose the safe landing.’ And we all laughed about that.”

But what started as a joke quickly turned into reality when Allen encountered a problem with his suit. “Just as the spacewalk was to begin my spacesuit failed,” Allen said.

It was an electrical failure in the spacesuit. When one is in a spacesuit, and you power it up, you hear a very high pitched hum there someplace in your ear, just a high-frequency hum. When I powered mine on, the hum started, but it didn’t sound like it was healthy. It sounded, indeed, more like an angry mosquito. It just changed its pitch. I’d never heard it before. Then I proceeded to make various electrical checks of the suit systems, and none passed the check. So we tried all sorts of things, powering it on and off and it was just not going to work, a very bitter disappointment to me, without any question. It was equally bitter to Bill, and the question now was, could he even do just a little part of a space – walk—a short solo, if you will. . . . But Mission Control said, “No buddy system, no spacewalk." Bill was really upset, obviously.

After the crew’s return to Earth, engineers analyzing the failure determined that the suit had a serious electrical problem but one that could be easily repaired for future spacewalks. “The bad news was the spacesuit failed; the good news was we were not outside the ship when it failed,” Allen noted. “It would have been considerably more traumatic had it failed outside. It would not have been fatal to me, but it would have gotten my attention, for sure. I would have to scramble to get back in, button myself up, and get out of the suit before other parts of it started to fail.”

Brand recalled how, as commander, he made the call that cost his mission its place in history as the first shuttle with spacewalks: “I guess I was the bad guy. As much as I hated to, I recommended to the ground that we cancel the evas, because we had a unit in each spacesuit fail in the same way. . . . We could have taken a chance and. . . could have done it, the eva, but we didn’t. I’m not sure Bill Lenoir was ever very happy about that, because he and Joe, of course, wanted to go out and have that first eva.”

For the first four-person crew and the largest yet to inhabit the orbiter, living aboard the spacecraft for the duration of the five-day mission created interesting challenges when it came to sharing the small amount of habit

able space. For example, there were no sleeping compartments, Brand said, so they had to be creative in each finding a place of his own for rest. “Since we didn’t have a sleep station, I just would take a string and tie it to my belt, and tied the other end to the wall. Tethered by the string, I’d put on a jacket and just fall asleep. It was great in weightlessness, and I slept well.” Bob Overmyer used the only sleeping bag and slept in the lower deck of the Space Shuttle, while Bill Lenoir slept in a corner on the upper deck. “I don’t know how he did it, but he didn’t float out of the corner, and he would sleep that way,” Brand said. “Joe Allen was the funniest. He would just free-float through the spacecraft the whole night, or what we called night. He moved gently, and the air currents would move him around. He might gently bump into a switch or something, but they were covered and he was hitting them so gently that there wasn’t really any concern about moving the switches. That was really humorous, seeing that.”

As with the demonstration flights, mission objectives included checking out the orbiter systems and determining their capabilities and tolerances. One such task, Brand explained, was to test the orbiter’s thermal tolerances by positioning the vehicle so that one side was fully in the sun and the other side was in shadow. “Sometimes after spending many tens of hours in one attitude, the shady side of the ship would get real cold,” Brand recalled. “Dew would form on the inside of the ship on the cool side. We had a treadmill in the mid-deck, and when people ran on the treadmill, it shook that dew loose and it would sort of rain inside the spacecraft.”

Allen, who would later publish a book featuring on-orbit photography, explained that NASA regulations almost prohibited him from taking a historic photo of the first time four Americans were together in space. In preparing for the mission, he discovered that the delayed shutter release button on his camera had been removed.

I went back to the photo people and I said, “This is a defective camera. It’s been plugged. I want a real Nikon. ” Well, it had been modified, and the modification had cost tens ofthousands ofdollars in order to make it more astronaut-proof such that astronauts didn’t, by mistake, put the camera on delayed timing and thus mess up a picture. A couple of modifications had been done, none of which was necessary, all of which were costly, and I just was very upset with my colleagues. I said, “Cameras are amongst the best-tested of complicated tools that we have humans have. They’ve been tested in wars. They’ve been tested in violent storms. They’ve been tested at the bottoms of the oceans. They’ve been tested everywhere. Why are you making them better?" Well, it was an argument I did not win.

Not to be deterred, Allen was determined to find another solution to the issue.

Perhaps in spite of the rules and because I’ve been a little bit of a troublemaker, but not serious trouble, I went to a camera store and was able to find a very old-fashioned shutter release mechanism…. I took this device aboard the spaceship without anybody really knowing it, and it came secretly off the spaceship on my person. This was against NASA regulations, and I will readily admit to it. But in the flight photos that came back, there were numbers of photos of us, the four crewmen. [One was] good enough to appear in Time magazine the next week. But this was with a camera that had no delayed shutter release! Not one NASA person said a word to me about it, but you knew that the people in the photo shops wondered how in the world those photographs were taken. A very nice man ran NASA Photo for many years; when he retired, I gave him that secret shutter release device—a flown object. . . . Because I knew he knew how I’d made that photo. He just had to know how I’d done it.

At last, it was time to return to Earth. Brand, who had previously experienced reentry in an Apollo capsule at the end of his Apollo-Soyuz mission, said his return to Earth on the shuttle was a very different experience.

There were very large windows, and you weren’t looking backwards at a donut of fire. You were able to see the fire all around you; you could look out the front. First the sky was black, because you were on the dark side of the Earth, but as this ion sheet began to heat up, you saw a rust color outside, then that rust color turned a little yellowish. Eventually, around Mach 20, you could see white beams or shockwaves coming off the nose. If you had a mirror—and I did on one of my flights—you could look up through the top window, which was a little behind the crew’s station, and see a pattern and the fire going over the top of the vehicle, vortices and that sort of thing.

The crew landed at Edwards Air Force Base at 6:33 on the morning of 16 November 1982. “We had an intentional max braking test and completely ruined the brakes,” Brand said. “I had to stomp on them as hard as I could. . . . Even though it was billed as the first commercial flight, I think we had roughly fifty flight-test objectives. That braking test was just one of them. We ruined the brakes, completely ruined them, but it was a test to see how well they would hold together if you did that.”

sts-6

Crew: Commander Paul Weitz, Pilot Bo Bobko, Mission Specialists Story Musgrave and Don Peterson

Orbiter: Challenger

Launched: 4 April 1983

Landed: 9 April 1983

Mission: Deployment of TDRS-г; first flight of Challenger; first shuttle spacewalk

Paul Weitz, Bo Bobko, Story Musgrave, and Don Peterson were not, at first, officially the crew of the sixth Space Shuttle mission. Like the members of the other early crews, they were given a letter designation, F, when they participated in the development of the Orbiter Flight-Test program. The crew members nicknamed themselves “F Troop,” a reference to a television comedy series featuring an Old West army troop. The crew even took an F Troop—themed crew photo. “We had on the little flight T-shirts and the flight pants,” sts-6 mission specialist Don Peterson recalled,

but we went out and bought cowboys hats. I had a sword that had once belonged to some lieutenant in Napoleon’s army. We got a Winchester rifle, the lever-action rifle, and a bugle and a cavalry flag, and we posed for this picture. Weitz, of course, is the commander, and he’s sitting there very stern looking, with the sword sticking in the floor. I had the rifle, and I think Story had the bugle. Anyway, we had that picture made, and we were passing them out, and nasa asked us not to do that. They thought that was not dignified, but I thought it was hilarious. I still have a bunch of them.

While the crew members embraced the F Troop nickname, there was another nickname used mainly behind their backs. “I didn’t hear ‘the Geritol bunch’ until, I guess, after the flight was over,” recalled sts-6 commander Weitz, who had been selected as a member of NASA’s fifth astronaut class seventeen years earlier. “Maybe that was something that everybody said about us when we weren’t around. We were on orbit and somebody was

talking about ‘how old you guys are.’ We had taken a bunch of pictures, and I couldn’t resist, I said, ‘You know, we’re not going to show the pictures to anybody under thirty-five when we come back. So some of you guys, some of you wiseasses, won’t see them.’”

sts-6 had three major mission objectives. It was the maiden launch of the second operational orbiter, ov-099, better known as Challenger, and so the crew would be making sure the new vehicle operated properly. The flight was to make the first deployment of a Tracking and Data Relay Satellite, part of a new space-based communications system. And, after the problems with the spacesuits on STS-5, this flight would now be making the first shuttle-based spacewalk.

Peterson and Musgrave were responsible for the deployment of the TDRS – 1 satellite on the first day of the mission. “Story’s the kind of guy that he wants to throw the switches,” Peterson recalled, “so what I did was took the checklist. Story was not real good about following the checklist, and so you had to kind of say, ‘Wait, Story. Let’s go step-by-step here and make sure we get this right.’”

A few days before launch, while the crew was quarantined in the crew quarters at Cape Canaveral, Peterson and Musgrave were informed that changes had been made to the software they would use to deploy the satellite. “These two guys showed up and. . . said they were from Boeing. They had badges. . . . Story and I literally copied a bunch of stuff down with pen and ink and used that on orbit,” Peterson said. “And that’s really scary, because, you know, you’re taking these guys’ words. You’ve never seen some of this stuff in the simulator. It’s, like, suppose what they’re telling us is not right, and we do something and we mess up the payload. Then they ain’t never going to find those two guys again. They’ll be gone, and it’ll be, like, ‘Why the hell didn’t you guys do it the way you were trained to do it?’”

The deployment went as planned, but after deployment, one of the two solid rockets in the booster that was to transport the satellite from the shuttle’s orbit to its intended geosynchronous orbit failed. However, NASA was able to nudge the satellite into its proper orbit using extra fuel in the attitude control system that allowed the orientation of the satellite to be changed.

Bobko explained, “Luckily, they had planned to use the satellite for commercial purposes as well as NASA, and it was decided not to do that, but they didn’t make that decision in time to take off some of the extra fuel that

|

19. The deployment of the first Tracking and Data Relay Satellite, on sts-6- Courtesy nasa. |

was required for using the satellite commercially. So that fuel was available, and, luckily, that was what saved the satellite.”

Musgrave and Peterson also were assigned to make the first shuttle – based spacewalks. “It’s kind of funny,” Peterson said – “George Abbey, I think, had some people already picked out that he wanted to have the honor of doing the first spacewalk, and when that canceled, he said, ‘Well, we’ll have to slip now. It’ll take months to get another crew ready.’ Jim Abrahamson, who’s an old friend of mine, was the [associate] administrator. He called me on the phone and said, ‘Can you and Story do the spacewalk?’ And I said, ‘Yeah.’ So he said, ‘Okay. We’re going to do it on the next flight.’”

The late addition of the spacewalk didn’t give the astronauts much time to train. Peterson had very little experience in the extravehicular activity spacesuit, but Musgrave had represented the Astronaut Office in the suit’s development so he knew everything about the suit there was to know, Peterson said. “Story had spent, like, four hundred hours in the suit in the water tank, so he didn’t really have to be trained,” recalled Peterson. “Now, my training was pretty rushed, pretty hurried. I think I was in the water, I don’t know, fifteen, twenty times, but that’s really not enough to really know everything you need to know. But all we were doing was testing the suit and testing the airlock, so we weren’t really doing anything that was critical to the survival of the vehicle. We were just testing equipment, and the deal was, if something went wrong, you’d just stop and come back inside. So the fact that I wasn’t highly skilled in the suit really didn’t matter that much.”

Back during the Gemini program, NASA had determined that the best way to prepare for spacewalks was to make suited dives in a water tank. The spacesuit is weighted to make it “neutrally buoyant,” such that it doesn’t sink to the bottom or float to the surface; it just hangs there. The simulation of weightlessness isn’t perfect—inside the suit, the astronaut’s body is not floating; it’s supported by the suit. So if the astronaut turns upside down in the water tank, the weight is on his or her head and shoulders.

In orbit, because of the difference between the pressure inside the shuttle (approximately 15 pounds per inch) and the pressure inside the suit (4.3 pounds per inch), the spacewalkers needed to slowly adjust to the pressure in the suit to prevent them from getting what’s commonly called “the bends,” a condition caused by too much nitrogen in the blood. To purge their bodies of nitrogen, the astronauts breathed pure oxygen for approximately three and half hours. “While we were breathing oxygen for three and a half hours, you can’t really do anything,” said Peterson. “Story and I slept. I slept about two and a half hours, probably the best sleep I had on orbit, because you’ve got fresh oxygen coming in over your head, and it kind of makes a nice whishing sound, and there’s no other noise. . . . People asked, ‘How in the world can you sleep just before you’re getting ready to go?’ I said, ‘Well, you know, you get tired enough, you can sleep almost anywhere.’”

After prebreathing was complete, the crew started pressure checking the suit, lowering the pressure in the airlock while the suit pressure regulator maintained 4.3 psi. Once it was demonstrated that suits were maintaining pressure properly, the hatch was opened and the spacewalkers went outside.

Peterson said that during the spacewalk his suit leaked pretty badly for about twenty seconds and then stopped. The ground didn’t know about the leak at the time or they would have stopped the eva, he said. “I was working with a ratchet wrench. We were just testing tools and stuff. We had launched a satellite out of a big collar that’s mounted in the back of the orbiter, and the collar. . . had to be tilted back down before we could close the payload bay doors and come home. So instead of driving it with the electric motors, they said, ‘Let’s go back and see if we can crank it down with a wrench, to simulate a failure. Suppose it failed, and we’ll see if we can do that.’”

Peterson chose not to use the foot restraints provided to help hold him in place, believing it took too long to set them up and move them around.

So I just held on with one hand, actually, to a piece of sheet metal, which is not the best way to hold on, and cranked the wrench with my other hand, and my legs floated out behind me. So as I cranked, my legs were flailing back and forth, like a swimmer, to react to the load on the wrench. The waist ring was rotating back and forth, and the seal in the waist ring popped out, and the suit leaked bad enough to set offthe alarms. We did not know what it was. I stopped and said, “I’ve got an alarm." Story stopped what he was doing and came over.

The seal popped back in place and the leak stopped, and the astronauts finished the eva.

“In those days we didn’t have constant contact with the ground,” Peterson added. “They didn’t see that. They weren’t watching at the time that that happened. They didn’t have any way to watch. By the time we dumped the data from the computer to the ground that showed that leak, we were already back inside the orbiter. Then they called up, and they were all upset about what happened here and what was that. We said, ‘Well, we really don’t know. We got an alarm. The alarm stayed on for about twenty seconds or so, and then it went off, and everything seemed okay. So we just finished what we were doing.’”

At the time, it wasn’t known what caused the alarm. The best guess after the mission was that Peterson had been working so hard that he had been breathing more heavily, forcing a higher oxygen feed level and setting off the alarm, an explanation Peterson found dubious. It wasn’t until two years later when a similar thing happened to astronaut Shannon Lucid during an eva training exercise that NASA figured out what really happened. Lucid was in her suit in a vacuum chamber walking on a treadmill when an alarm in her suit alerted that the oxygen flow rate was too high.

“That means that you’re pumping oxygen from the tank into the suit, but that also means the oxygen is going somewhere,” explained Peterson. “It’s going out of the suit somewhere. So they knew they had a leak in her case, and they could also see the oxygen coming into the vacuum chamber, because they were getting pressure inside the chamber.”

Lucid stopped walking, and when she stood still, the leak stopped. A technician there recalled that something similar had happened on STS-6. “They went back and got the video of my flight and looked at it,” said Peterson.

He said—and this is kind of interesting—when Shannon Lucid was walking, since she’s a woman, her hips swivel, and her suit was actually rotating, and we’d never seen that with a guy because guys don’t walk that way. But he said, “That’s the same thing that happened to Peterson’s suit two years ago. ” So then they went in and changed the seals and all and fixed the problem. But it always amazed me that those guys were dedicated enough to have that kind of memory fixed in their heads. . . . Of course, I got a lot of insulting calls from that guy, “You know, your hips move just like Shannon’s. ” I said, “Not for you. ”

The eva afforded the two spacewalkers an amazing opportunity to do some stargazing. While the Space Shuttle normally flies with the payload bay toward Earth all the time, Peterson and Musgrave thought it would be neat to look out at the night sky during one of the passes over the dark side of Earth. “We went to the flight control team and said, ‘Guys, when we get on the dark side, we’d like you to roll the vehicle over so we can look out,’” recalled Peterson.

Pete Frank said, “Oh, just for you guys’ amusement, you want us to roll the damned vehicle upside down?” And we said, “Yes, you know, wouldn’t that be great?” So what they did was even better than that. When they were on the daylight side at noon, they went into what I called the Ferris wheel mode. . . . We went around the Earth holding one [orientation, relative to the sun]. So we went around the Earth so that when we got on the dark side, we were faced exactly away. But because they did that, with the cameras running and all, we got some beautiful pictures of the Earth from a lot of different attitudes that we wouldn’t have gotten otherwise. So we got on the dark side, and Paul Weitz, the commander, said, “Okay, guys, you asked for this. Now stop whatever the hell you’re doing and look." So we did, and there’s lot of light in the payload bay, and the helmet’s got these big things. You couldn’t see anything. I mean, it was just too much glare. So we got over in one corner and kind of shielded our eyes, and you could see a little patch of sky, but that was about the best we could do.

Peterson was surprised that if he was in a place where sunlight shone into the helmet, he could feel the sunlight on his face. “The visor protects you from the ultraviolet and all that, but you could feel the heat as soon as the sun came in through the visor.”

While the views were interesting, Peterson described the eva spacesuit as extremely stiff and said the gloves were hard to work in.

eva would be fun if the suits weren’t so hard to work in. The suits are fairly uncomfortable. .. . They’re not pressurized like an automobile tire, but they’re pressurized so they’re fairly rigid. The suit has a neutral position. If you just blow the suit up and nobody is in it, it goes to a certain position. If you move it away from that position, it tries to come back because the arms and all are very rigid and they’re under pressure. So anytime you’re doing anything in the suit, you’re typically fighting against the suit itself. The gloves are the same way. If you look at a lot of photography from spacewalks, you see people don’t grab something like [they would on Earth], because to do that, you’ve got to fight the glove. They wedge things between their fingers, and that way you don’t have to exert pressure.

The fit of the suit was very important. Because the body expands a little bit in zero g, the fit of the suit has to allow for a certain amount of expansion, and they really can’t replicate that expansion on the ground, meaning that the suits generally fit tightly. “When I stood up in it, I could plant my heels against the heels of the boot, and the shoulder harness was right against my shoulders, and the top of my head was right against the top of the helmet,” recalled Peterson.

The gloves have to be really close to your fingertips. If they’re more than about an eighth of an inch off you’ll lose your ability to feel things and to do precise movements. The problems we had had was, at least in some of the early programs, the gloves were too tight on the fingertips. What they’d do is they’dpinch your fingernail. Several guys lost their fingernails; not while they were in orbit, but it pinched them so bad that it pulled the roots loose in the back. It’s very uncomfortable. I mean, it used to be a form [of] medieval torture once to hurt people’s fingernails.

STS-7

Crew: Commander Bob Crippen, Pilot Rick Hauck, Mission Specialists John Fabian, Sally Ride, and Norm Thagard Orbiter: Challenger Launched: 18 June 1983 Landed: 24 June 1983

Mission: Deployment of two communications satellites

With the sixth shuttle mission completed, Bob Crippen, pilot of the first shuttle mission, was about to become the first astronaut to fly on the vehicle twice, this time as commander of STS-7. Historically, the commander had been the most prominent member of the crew, but that was certainly not the case with STS-7, a fate that Crippen had a hand in bringing upon himself. “I essentially helped pick the crew, with John [Young] and George [Abbey], so I would say I had a great deal of influence. And yes, the crew was ‘Sally Ride and the others,’ which was just right for us.”

Before Ride could become the first female NASA astronaut to fly in space, two important decisions had to be made. First was the decision as to whether the time was right for the historic move of including a woman on a NASA spacecraft crew. That decision, Crippen said, was an easy one. The flight would be the first to be crewed by members of the TFNG class of astronauts. Since, of the twenty-one mission specialists in the class, six were female, it seemed appropriate to Crippen and his superiors that one of them should be chosen for the crew.

That decision was followed by another: who would be chosen for a place in the history books. “They were all good, and any of them could have been the first one,” Crippen said.

I thought Sally was the right person for that flight for a number of reasons. She was one of our experts on the remote manipulator system, which was critical to what we were doing on this mission. I liked her demeanor, the way she behaved. She fit right in with everybody, as all of them did, but we just got along well, and I thought that’s really important when you’ve got a crew, because you’ve got to work together. I knew that she would integrate well with the other crew members that we were going to have on board, which initially was just going to be Rick Hauck and John Fabian and myself. We later added Norm Tha – gard to that flight as well. But she was just the right person to do it at the time.

Ride recalled being informed of her selection to the crew and the distinction of being the first American woman in space.

I met alone with Mr. Abbey, which is a little bit unusual. The commander is the first to know about a flight assignment; Bob Crippen, who would be the commander of my crew, had already been told. But then usually the rest of the crew is told together; at least that was the way that it was done then. But in this case, Mr. Abbey told me first, before he called over the other members of the crew. After I met with him, he took me up to Dr. Kraft’s office and Dr. Kraft talked with me about the implications of being the first woman. He reminded me that I would get a lot of press attention and asked if I was ready for that. His message was just, “Let us know when you need help; we’re here to support you in any way and can offer whatever help you need." It was a very reassuring message, coming from the head of the space center. [My family] were pretty excited. They knew that this was something that I’d wanted to do for a long time. After all, I’d been in training for ^four years when I heard the news, so they’d been preparingfor this eventuality for four years. They were really excited when I got assigned to a flight.

Ride said nasa did a good job protecting her and the rest of the crew from too much media attention prior to the mission so the astronauts could focus on their mission objectives. “I did very few interviews from the time that we entered training until our crew press conference and the interviews afterward,” recalled Ride.

Then we did no more interviews until our preflight press conference about a month before the flight. Right after that press conference, we did a day of solid interviews. NASA protected me while we were in training, and even the day that we did all our interviews, we did them in pairs. I did most of my interviews with Rick Hauck or Bob Crippen. NASA’s attitude was, “She’s going to get all the attention, and we need to help her." And they did. They did a really good job shielding me from the media so that I could train with the rest of the crew and not be singled out. We also tried to get across that spaceflight really is a team thing.

The training leading up to the flight was particularly intense. Only the commander, Bob Crippen, had flown before, which meant the four rookies had a lot to learn. “The training really accelerated and intensified during that two months before the flight,” recalled Ride. “I was spending virtually

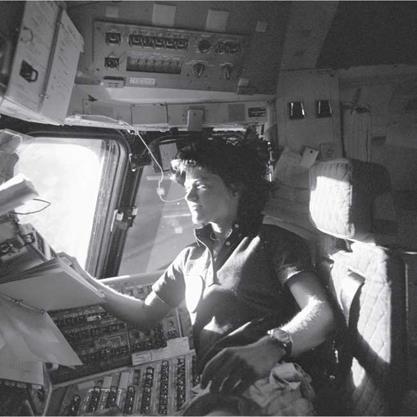

|

20. Sally Ride on the flight deck during sTs-7. Courtesy nasa. |

all my time trying to learn things, what I’d learned, practice and just stuff that one last fact into my brain. I was barely watching the news at night and really wasn’t aware of all the attention. Of course, I was a little bit aware of it—I couldn’t help but be—but it wasn’t impacting my training at all.” Ride’s inclusion on STS-7 created learning opportunities for ground support teams accustomed to all-male astronaut crews. By that point, the jsc team had already been through any number of big-picture changes, such as the locker-room question. Now they were discovering all the little changes that went along with integrating shuttle crews. For example, every item astronauts would use in space had to be chosen and reviewed before flight. “The engineers at nasa, in their infinite wisdom, decided that women astronauts would want makeup,” Ride recalled.

So they designed a makeup kit. A makeup kit brought to you by NASA engineers. You can just imagine the discussions amongst the predominantly male engineers about what should go in a makeup kit. So they came to me, figuring that I could give them advice. It was about the last thing in the world that I wanted to be spending my time in training on. So I didn’t spend much time on it at all. But there were a couple of other female astronauts who were given the job of determining what should go in the makeup kit and how many tampons should fly as part of a flight kit. I remember the engineers trying to decide how many tampons should fly on a one-week flight. They asked, “Is one hundred the right number?” “No. That would not be the right number. ” They said, “Well, we want to be safe. ” I said, “Well, you can cut that in half with no problem at all. ” And there were probably some other, similar sorts of issues, just because they had never thought about what just kind of personal equipment a female astronaut would take. They knew that a man might want a shaving kit, but they didn’t know what a woman would carry.

Astronaut Rick Hauck recalled that Ride was very professional, very industrious, was always thinking about the objectives for the flight, and was also a good teammate with a good sense of humor. Reporters at press conferences would focus most of their inquiries on the first flight of a U. S. woman, and that was just fine with Hauck. “I remember one press conference just before we flew,” he said. “Someone from Time magazine or something said, ‘Sally, do you think you’ll cry when you’re on orbit?’ And of course, she kind of gave him this ‘You got to be kiddin’ me’ kind of look and said, ‘Why doesn’t anyone ever ask Rick those questions?’”

Norm Thagard was a late addition to the crew, chosen in order to address a particular issue that had been plaguing NASA crews since Apollo 9, and particularly since the Skylab missions in 1973. “nasa was concerned about this ‘space adaptation syndrome,’ or upchucking in space, and we wanted to learn more about it,” Crippen said. “We had some physicians in this thirty-five group, and we figured, ‘Well, we’ve only got four of us on board. There’s room for more. Why don’t we pick a doc, and let that individual go through and see if they can figure out this problem a little bit more?’”

Thagard was selected for the mission, and he and other physician-astronauts put together a series of experiments to determine the cause of space adaptation syndrome. “He was wanting some of us to participate in the exper

iments,” said Crippen. “When some of [us] weren’t really occupied with things, then we planned on going down there and seeing whether Norm could make us sick or not, which he worked very hard at.”

Hauck recalled being subjected to one of Thagard’s tests while in space.

As soon as we got on orbit, I got down into the middle deck, and Norm had these visual things that I had to watch, and they’re spinning, and, boy, I felt miserable. I mean, they accomplished their purpose. At one point I said, “Hey, guys, I’ve had it. I’m going to go into the airlock," which was just a nice place to go hide. And I said, “I’m going to close my eyes, and please don’t bother me until I come out. " I didn’t know whether I was going to throw up. I just felt miserable. And I guess it was about four hours later I started to come out of that and that resolved itself.

While STS-7 was best known among the American public for the inclusion of Ride in the crew, the primary mission objectives were a bit more practical. STS-7 would be the first shuttle flight to do “proximity operations,” to rendezvous with and capture another object in space. A Shuttle Pallet Satellite in the cargo bay of the shuttle was picked up with the remote manipulator system, taken out of the bay, released into space, and then recaptured.

Ride used the robotic arm to lift the small satellite out of the cargo bay and release it. Crippen then flew the shuttle approximately one thousand feet away from the satellite, circled around it, and rendezvoused, and Ride recaptured it with the robotic arm. “We were to evaluate how easy [or] how hard it was to maintain formation with the satellite,” said Hauck, who piloted the shuttle for the second set of rendezvous tests after Crippen flew the first set. “It was just wonderful to be the new guy on the block and be given this responsibility to do some of the flying around this satellite. It all went well, and we got a lot of good data and wrote up a good report on it.”

The proximity operations led to another historic moment for the Space Shuttle program: the first photo of the orbiter in space. Today, pictures of the orbiter in space are commonplace; the vehicle was imaged extensively during its rendezvous with the International Space Station. At the time of STS-7, however, that particular sight had never been seen. “While we were headed out, a guy by the name of Bill Green that works up at headquarters had come up with the idea of putting a camera on board this Shuttle Pallet Satellite,” Crippen said. “So we actually remotely took pictures of the shuttle from the satellite when it was about a thousand feet away, which gave us some unique shots when we returned back.”

Images of the orbiter in space were scripted into the mission objectives, but what wasn’t officially planned was an iconic shot of the orbiter with the robotic arm in the shape of the number 7. “On our mission patch we had had the orbiter with the arm up in the shape of a seven, so we concluded that, hey, we might as well do that,” recalled Crippen. “We had practiced this on the ground by ourselves, and I think it was Sally who put the arm in that configuration. When we took the picture, it almost looked like the patch. However, Mission Control had not seen the arm go into this particular position before, and they were worried that we were getting it into some limits that it shouldn’t be in. It wasn’t, but it did cause some consternation on the ground, I think.”

Fabian recalled planning the picture with Ride and Crippen.

We really worked hard on that, and we got a lot of help. We worked out the position, the arm in the shape of a seven for the seventh flight. And we didn’t tell anybody about this, of course. We had this on kind of a back-of-our-hand type of procedure, what angles each joint had to be in order for it to look like that. And then we had worked on the timing so that we could catch the Space Shuttle against that black sky with the horizon down below. That was the picture we most wanted. We most wanted the shuttle against the black sky and the Earth’s horizon down below. I was real proud of that. I was real proud of the work that Sally and I and Crip had done on getting that ready to go. Because it gave you a really strong indication that, you know, this is a spaceship we’re talking about here.

The mission also included the deployment of two communications satellites. Once in space, the astronauts opened the cargo bay doors and secured the Payload Assist Modules, which were the boosters used to move the satellites from the shuttle’s orbit to their higher destination orbit. “It was really important work, and we screwed it up a little bit,” Fabian said. “We threw the heater switches out of sequence, which in the simulations that we did would not have meant anything. But it turns out that those switches had been rewired to do a secondary function. It had nothing to do with the heaters. . . . It never got picked up by the trainers. It never got picked up by anyone that was associated with preparing us to go fly that there

|

21. Challenger in orbit on STS-7 with the remote manipulator system arm in the shape of the number 7. Courtesy nasa. |

was something quite different about these switches and that if you throw them at the wrong time, then something unexpected is going to happen.” Unbeknownst to the astronauts, flipping the switches in the wrong order caused the early extraction of several pins on the rotation table that were keeping the satellites from rotating prior to their deployment. “We didn’t know anything at all was wrong until the ground told us that we had inadvertently pulled the pins and that they were trying to find a work-around,” Fabian said. “They found a way to command from the ground to put the pins back in, fortunately. But this was one of those things; this is a very complex machine, and in spite of everybody’s best intentions, sometimes some things slip through the cracks. We had been through this thing in the simulator dozens, if not hundreds, of times, doing it precisely the way that we did it in orbit without it ever coming to anyone’s attention.”

With his promotion to commander on STS-7, Crippen was able to accomplish a goal that he had set for the position during sts-1: “I was the commander now, so I was going to get to look out the window more.”

In fact, Crippen encouraged his crew members, on STS-7 and all of his flights, to take advantage of the unique opportunities spaceflight offers as much as possible. “Enjoy it,” he said. “Enjoy it. You never know whether you’re going to get a second flight or whatever, so take advantage of when you go up, to really savor it. I had ended up with four flights, and I still remember them today, and every bit of it was enjoyable.”

During the mission, Ride talked to CapCom Mary Cleave, the first time a woman on the ground talked to a woman in space. Ride said it didn’t even cross her mind. “I don’t know whether it occurred to Mary either. I didn’t even think about it until after I landed and somebody pointed it out to me. And apparently the first time we talked we said something totally unmemorable. I don’t know what it was, but it was not particularly historic.” Cleave’s personal impression of the exchange from the ground was similar to Ride’s orbital experience, but she didn’t have to wait until after the flight to have it pointed out. “I didn’t even notice it. Here’s Sally and I, we didn’t even notice it. But I was on duty, and one female reporter, who will go unnamed, afterwards said, ‘Mary, it was so disappointing.’ And I said, ‘What do you mean?’ ‘You and Sally just had a normal conversation.’ ‘Yeah. We were working.’ ‘Well, you should have said something special for this momentous occasion.’ ‘What momentous—?’ ‘First female-to-female communication.’ And I went, ‘Oh, we didn’t notice.’ Sort of like, ‘Well, I’m sorry I disappointed you, but really we didn’t notice it.’”

One memorable event that occurred during the mission made a very literal impact. “We were hit on the windshield by a small fleck of paint, and it made a hole about the size of a lima bean halfway through the outer of two panes of glass,” recalled Fabian.

We found out after the flight that it was one [layer] of paint the size of a pinhead that had hit us. And it hits you with such enormous velocity that the kinetic energy associated with that small fleck of paint is enough to blast out that kind of a crater. Crippen decided not to tell the ground that we’d been hit, and it didn’t come up until after the flight. And his rationale for that, I assume, was that there wasn’t anything that the ground could do to help us. The event

had already occurred. We were perfectly safe. They would worry a lot. And so he elected not to say anything. I think after the flight someone said something about that, but I think it was the right decision.

Finally, the time for landing came, and went, and came again. STS-7 was to be the first shuttle flight to land at Kennedy Space Center, but weather was an issue. “John [Young] was the weather checker in our Shuttle Training Aircraft at Kennedy, and he saw some weather, which it can develop very rapidly, which he and I both know,” Crippen recalled. “He properly waved us off on that first time, and we elected to wait another day and try it. . . . But truthfully, that extra day we got on orbit was a free day. There wasn’t any real work to be done, so all of us had an opportunity to sit back and enjoy, and maybe play a little bit while we were on orbit.”

To fill the time the astronauts held the first-ever Olympics in space. According to Hauck, the crew was looking for ideas to kill time. “I forget which one of us said it—because this was near the Olympics—‘Let’s have a Space Olympics.’ Crip was a little wary of this, but he said, ‘Okay, what do you want to do?’” The rules were set. Each astronaut would start on the mid-deck, go through the portside access to the flight deck, across the flight deck to the starboard entryway, down and across the mid-deck, and back up to the top rung of the ladder to the flight deck. Speed was the goal.

“We gave out five awards,” Hauck said. “Sally won the fastest woman. John Fabian won the competitor that caused the most injuries. No one got hurt, but I think his leg hit Crip coming around at one point. I think Norm Thagard was the fastest man. Crip was the most injured, and I was the most something. I don’t know what it was.”

The next day it was time to try the landing again. Crippen’s promotion from pilot to commander meant that this time, as commander, he actually got to pilot, but his opportunity to make the first shuttle landing at Kennedy wasn’t to be—bad weather in Florida continued that day as well, and the landing was moved to Edwards. The shift scuttled some planned encounters—not only the astronauts’ reunions with family members waiting in Florida, but also a chance to meet President Ronald Reagan, who had planned to be on hand to welcome the crew home.

After landing, Crippen said, came the satisfaction of a job well done. “Anytime you work hard to do something and it comes out well, you can’t help but feel good, and that’s the way I felt with this. I felt my crew had done a superb job. We had accomplished all the mission objectives. We’d made the proximity operations look good. We had deployed a couple of communication satellites, and everything worked. So that gives you a nice high.”

After the flight, the attention returned to America’s first flown female astronaut. “I think that’s when all the attention really hit me,” Ride said.

While I was in training, I had been protected from it all. I had the world’s best excuse: “I’ve got to train, because I have this job to do." NASA was very, very supportive of that. So my training wasn’t affected at all. But the moment we landed, that protective shield was gone. I came face-to-face with a flurry of media activity. There was a lot more attention on us than there was on previous crews, probably even more than the sts-i crew. I’d done my share of public appearances and speeches before I’d gone into training, so I knew how to talk to the press and I knew how to go and show my slides and give a good speech. But just the sheer volume of it was something that was completely different for me, and people reacted much differently to me after my flight than they did before my flight. Everybody wanted a piece of me after the flight.

As commander of the mission, Crippen said he felt a responsibility to shield Ride from any unwanted attention. “She was a big hero as we went around, and everybody wanted to meet Sally. There were so many people trying to get after her or get to her, for whatever reason, that part of the commander’s job was to make sure that she was protected from that, without being overprotective; just whatever she wanted to make sure that she didn’t get overwhelmed by it.”

sts-8

Crew: Commander Dick Truly, Pilot Dan Brandenstein, Mission

Specialists Dale Gardner, Guion Bluford, and Bill Thornton

Orbiter: Challenger

Launched: 30 August 1983

Landed: 5 September 1983

Mission: Launch of Indian satellite, microgravity research

While STS-7 marked the first flight of a female American astronaut, sts – 8 broadened the diversity of the astronaut corps further, with the launch of Guy Bluford, NASA’s first African American astronaut to fly. As with Ride’s flight, there was interest from the media and the public in the first African

American in space. Bluford became a role model for young African Americans. On the twentieth anniversary of his first flight, Bluford said in a nasa interview that it had never been his goal to be the first African American in space. “I recognized the importance of it, but I didn’t want to be a distraction for my crew. We were all contributing to history and to our continued exploration of space. I felt I had to do the best job I could for people like the Tuskegee Airmen, who paved the way for me, but also to give other people the opportunity to follow in my footsteps.”

Again, as with Ride, nasa protected Bluford from too much media attention before the flight so he could focus on preparing for the mission. He was also spared somewhat because there was a lot of attention still on Ride, whose historic flight had occurred just two months prior.

The crew started out as a crew of four, but approximately five months before the flight Bill Thornton joined the crew to continue studies on space adaptation syndrome, just as Thagard had done on STS-7.

The primary task of the mission was the launch of the Indian insat – ib communications and weather satellite. “We were launching a satellite for India,” explained mission pilot Dan Brandenstein, “and to get it in the proper place, you kind of worked the problem backwards. Okay, they want the satellite up here, so then you’ve got to back down all your orbital mechanics and everything, and basically it meant we had to launch at night. The fact we launched at night meant that we would end up landing at night.”

This would be first time the shuttle would launch and land in the dark. Bluford said the crew trained for the nighttime launch and landing by turning out the lights in the Space Shuttle simulator. “We learned to set our light levels low enough in the cockpit so that we could maintain our night vision, and I had a special lamp mounted on the back of my seat so that I could read the checklist in the dark,” recalled Bluford. “The only thing that wasn’t simulated in our launch simulations was the lighting associated with the solid rocket boosters’ ignition and the lighting associated with the firing of the pyros for srb and external tank separation. No one seemed to notice this omission until after we flew.”

That omission set the astronauts up for quite the surprise during the actual launch. “We had darkened the cockpit to prepare for liftoff; however, when the srbs ignited, they turned night into day inside the cockpit.

|

22. Guion Bluford exercises on the treadmill during sts-8. Courtesy nasa. |

Whatever night vision we had hoped to maintain we lost right away at liftoff,” said Bluford.

Space Shuttle Challenger launched in the wee hours of the morning on 30 August 1983. “We were crossing Africa when I saw my first sunrise on orbit,” Brandenstein reflected, “and to this day, that is the ‘Wow!’ of my spaceflight career. Sunrises and sunsets from orbit are just phenomenal, and obviously the first one just knocked my socks off. It’s just so different. It happens relatively quickly because you’re going so fast, and you just get this vivid spectrum forming at the horizon. When the sun finally pops up, it’s just so bright. It’s not attenuated by smog, clouds, or anything. It’s really quite something.”

Bluford also had fond memories of that first sunrise in space. “I still remember seeing the African coast and the Sahara Desert coming up over the horizon. It was a beautiful sight. Once we completed our oms burns, I unstrapped from my seat and started floating on the top of the cockpit. I remember saying to myself, ‘Oh, my goodness, zero g.’ And like all the other astronauts before me, I fumbled around in zero g for quite a while before I got my space legs.”

It proved to be a good thing the sunrise was quick because the astronauts didn’t have time to enjoy the scenery. “After you’re on orbit, you’re floating around and that’s neat, and you’re getting to see the view and that’s neat,

but after you get up, you’ve got an awful lot to do in a very short time, getting the vehicle prepared to operate on orbit,” Brandenstein said. “There are checkpoints. If you don’t get things done or something doesn’t work right, you have to turn right around and come back, so you’re pretty much focused for about the first four hours up there, of getting that all done. Once that was done, well, then you look out the window a little bit more. I remember when the real work of the day was pretty much over and it was time to go to sleep, you didn’t. You looked out the window.”