First Flight

Well, we were just finally glad to get it started.

Geez, we’d waited so long. . . . We’re finally getting

back into the flying business again.

—Astronaut Owen Garriott

STS-I

Crew: Commander John Young, Pilot Bob Crippen

Orbiter: Columbia

Launched: 12 April 1981

Landed: 14 April 1981

Mission: Test of orbiter systems

It was arguably the most complex piece of machinery ever made. And it had to work right the first time out. No practice round, just one first flight with two lives in the balance and the weight of the entire American space program on its shoulders.

The Redstone, Atlas, and Titan boosters used in the Mercury and Gemini programs had flight heritage prior to their use for manned NASA missions, but even so, the agency ran them through further test flights before putting humans atop them. And thankfully so, since their conversion from missiles into manned rockets was not without incident. There was the Mercury-Redstone vehicle that flew four inches on a test flight before settling back onto the pad. Or the Mercury-Atlas rocket that exploded during a test flight before the watching eyes of astronauts who were awaiting a ride on the launch vehicle in the future.

Unlike those used in Mercury and Gemini, the Saturn rockets used in the Apollo missions were newly designed by NASA for the purpose of manned

spaceflight and had no prior history. When the first unmanned Saturn V was launched fully stacked for an “all-up” test flight in 1967, it was a major departure from the incremental testing used for the smaller Saturn I, in which the first stage was demonstrated to be reliable by itself before being flown with a live upper stage. The decision to skip the stage-by-stage testing for the Saturn V was a key factor in meeting President John F. Kennedy’s “before this decade is out” goal for the first lunar landing, but it was not without a higher amount of risk.

That risk, however, paled next to the risk involved in the first flight of the Space Shuttle system. Not only could there be no incremental launches of the components, but there would be no unmanned test flight, no room for the sorts of incidents that occurred back in the Mercury testing days. The first Space Shuttle launch would carry two astronauts, and it had to carry them into space safely and bring them home successfully. Although it would be well over a decade before a movie scriptwriter would coin a phrase that would define the Apollo 13 mission, it definitely applied in this case: failure was not an option.

Rather than being upset over the greater risk, however, NASA’s astronauts endorsed the decision, some rather passionately. Most of the more veteran members of the corps had come to NASA as test pilots, and they were about to be test pilots again in a way they had never before experienced as astronauts. In fact, some pushed against testing the vehicle unmanned because of the precedent it would set.

“Oh, we were tickled silly,” said Joe Engle, “because we didn’t want any autopilot landing that vehicle.”

Conducting an unmanned test flight would mean developing the capability for the orbiter to fly a completely automated mission, meaning that it would be capable of performing any of the necessary tasks from launch to landing. Some in the Astronaut Office were concerned that the more the orbiter was capable of doing by itself, the less NASA would want the astronauts to do when crewed flights began.

“We were very vain,” Engle added,

and thought, you’ve got to have a pilot there to land it. If you’ve got an airplane, you’ve got to have a pilot in it. Fortunately, the certification of the autopilot all the way down to landing would have required a whole lot more cost and development time, delay in launch, and I think the rationale that we put forward

|

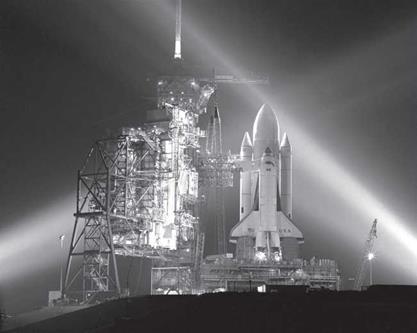

12. Space Shuttle Columbia poised for takeoff of sts-i. Courtesy nasa. |

to discourage the idea of developing the autoland—and I think [a] correct one, too—was that you can leave it engaged down to a certain altitude, but always you have to be ready to assume that you’re going to have an anomaly in the autopilot and the pilot has to take over and land anyway. The pilot flying the vehicle all the way down—approach and landing—he’s in a much better position to affect the final landing, having become familiar and acclimated to the responses of the vehicle after being in orbit and knowing what kinds of displacements give him certain types of responses. Keeping himself lined up in the groove coming down to land is a much better situation than asking him to take over after autopilot has deviated off.

According to astronaut Hank Hartsfield, one of the major technical limitations that made the idea of an unmanned test flight particularly challenging was that the shuttle’s computer system—current for the day but primitive by modern standards—would have to launch with all of the software needed for the entire mission already set up; there would be no crew to change out the software in orbit.

“We had separate software modules that we had to load once on orbit,” Hartsfield explained. “All that had to be loaded off of storage devices or carried in core, because, remember, the shuttle computer was only a 65K machine. If you know much about storage, it’s small, 65k. When you think about complexity of the vehicle that we’re flying—a complex machine with full computers voting in tight sync and flying orbital dynamic flight phase and giving the crew displays and we’re doing that with 65K of memory—it’s mind-boggling.”

Acknowledging the test-flight nature of the first launches, a special modification was made to Columbia—ejection seats for the commander’s and pilot’s seats on the flight deck. According to sts-i pilot Bob Crippen, the ejection seats were a nice gesture but, in reality, probably would have made little difference in most scenarios.

“People felt like we needed some way to get out if something went wrong,” Crippen said.

In truth, if you had to use them while the solids were there, I don’t believe if you popped out and then went down through the fire trail that’s behind the solids that you would have ever survived, or if you did, you wouldn’t have a parachute, because it would have been burned up in the process. But by the time the solids had burned out, you were up to too high an altitude to use it.

On entry, if you were coming in short of the runway because something had happened, either you didn’t have enough energy or whatever, you could have ejected. However, the scenario that would put you there is pretty unrealistic. So I personally didn’t feel that the ejection seats were really going to help us out if we really ran into a contingency. I don’t believe they would have done much for you, other than maybe give somebody a feeling that, hey, well, at least they had a possibility of getting out. So I was never very confident in them.

Risky or not, the two crew assignment slots that were available for the mission were a highly desired prize within the astronaut corps. sts-i would be the first time any U. S. astronaut had flown into space in almost six years, would offer the opportunity to flight test an unflown vehicle, and would guarantee a place in the history books. Everyone wanted the flight. Senior astronaut John Young and rookie Bob Crippen got it.

Crippen recalled when he learned that he would be the pilot for the first Space Shuttle mission but said he still didn’t know exactly why he was the one chosen for the job.

“Beats the heck out of me,” he said.

I had anticipated that I would get to fly on one of the shuttle flights early on, because there weren’t that many of us in the Astronaut Office during that period of time. I was working like everybody else was working in the office, and there were lots of qualified people. One day we had the Enterprise coming through on the back of the 747. It landed out at Ellington[Field, Houston]. . . . I happened to go out there with George Abbey, who at that time was the director of flight crew operations. As we were strolling around the vehicle, looking at the Enterprise up there on the 747, George said something to the effect of, “Crip, would you like to fly the first one?”

About that time I think I started doing handsprings on the tarmac out there. I couldn’t believe it. It blew my mind that he’d let me go fly the first one with John Young, who was the most experienced guy we had in the office, obviously, and the chiefofthe Astronaut Office. It was a thrill. It was one ofthe high points of my life.

To be sure, Crippen’s background made him an ideal candidate for the position. Crippen had been brought into NASA’s astronaut corps in 1969 in a group that had been part of the air force’s astronaut corps. After the cancellation of the air force’s Manned Orbiting Laboratory program, NASA agreed to bring most of the air force astronauts who had been involved in the mol program into the NASA astronaut corps.

Crippen’s first major responsibility at NASA was supporting the Skylab space station program, followed by supporting the shuttle during its development phase. “I guess all that sort of added up, building on my experience. Working on the shuttle, I did primarily the software stuff, computers, which I enjoyed doing. And I think all that, stacked up together, kind of opened up the doors for me to fly. . . . I’m not sure whose decision that was, whether it was John Young’s, George Abbey’s, or who knows, but I’m sure glad they picked me.”

Interestingly, Crippen had been part of the earliest wave of college students who had amazing opportunities open up for them by becoming savvy in the world of computer technology. During his senior year he took the first computer programming class ever offered at the University of Texas. “Computers were just starting to—shows you how old I am—to be widely used. . . . Not pcs or anything like that, but big mainframe kind of things, and Texas offered a course, and I decided I was interested in that and I

|

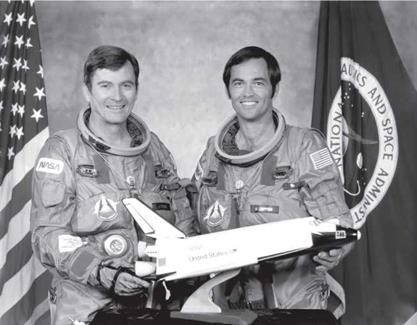

13. sts-i crew members Commander John Young and Pilot Bob Crippen. Courtesy nasa. |

would try it. It was fun. That was back when we were doing punch cards and all that kind of stuff.”

With that educational background under his belt, Crippen took advantage of an opportunity with the air force Manned Orbiting Laboratory program to work on the computers for that vehicle. That in turn carried over, after his move to nasa, to working on computers for Skylab, which were similar to the ones for mol.

“It was kind of natural, when we finished up Skylab and I started working on the Space Shuttle, to say, ‘Hey, I’d like to work on the computers,’” Crippen said. “T. K. Mattingly was running all the shuttle operations in the Astronaut Office at that time and didn’t have that many people that wanted to work on computers, so he said, ‘Go ahead.’ . . . The computer sort of interfaced with everything, so it gives you an opportunity to learn the entire vehicle.”

Of course, being named pilot for sts-i didn’t mean that Crippen would actually pilot the vehicle. “We use the terms ‘commander’ and ‘pilot’ to confuse everybody, and it’s really because none of us red-hot test pilots want to be called a copilot. In reality, the commander is the pilot, and the pilot

is a copilot, kind of like a first officer if you’re flying on a commercial airliner. [My job on sts-1] was primarily systems oriented, working the computers, working the electrical systems, working the auxiliary power units, doing the payload bay doors.”

Crippen considered it an honor to work with the senior active member of the Astronaut Office for the flight. “When you’re a rookie going on a test flight like this, you want to go with an old pro, and John was our old pro,” he said.

He had four previous flights, including going to the moon, and John is not only an excellent pilot, he’s an excellent engineer. I learned early on that if John was worried about something, I should be worried about it as well. This was primarily applying to things that we were looking into preflight. It’s important for the commander to sort of set the tone for the rest of the crew as to what you ought to focus on, what you ought to worry about, and what you shouldn’t worry about. I think that’s the main thing I got out of John.

Crippen described Young as one of the funniest men he ever knew and regretted that he didn’t keep record of all the funny things Young would say. “He’s got a dry wit that a lot of people don’t appreciate fully at first,” Crippen said, “but he has got so many one-liners. If I had just kept a log of all of John’s one-liners during those three years of training, I could have published a book, and he and I could have retired a long time ago. He really is a great guy.”

The crew was ready; the vehicle less so. There were delays, followed by delays, followed by delays. Recalled astronaut Bo Bobko, “John Young had come up to me one day and said, ‘Bo,’ he said, ‘I’d like you to take a group of guys and go down to the Cape and kind of help get everything ready down there.’ And he said, ‘I know it’s probably going to take a couple of months.’ Well, it took two years.”

Much of that two years was waiting for things beyond his control, things taking place all over the country, Bobko said. However, he said, even the time spent waiting was productive time. He and others in the corps participated in the development and the testing that were going on at the Cape. Said Bobko,

Give you an example. I gave Dick Scobee the honor of powering up the shuttle the first time. I think it was an eight o’clock call to stations and a ten o’clock test start in the morning. I came in the next morning to relieve him at six, and he

|

14. Space Shuttle Columbia arrives at Launchpad 39A on 29 December 1980. Courtesy nasa. |

wouldn’t leave until he had thrown at least one switch. They had been discussing the procedures and writing deviations and all that sort of thing the whole day before and the whole night, and so they hadn’t thrown one switch yet. So there was a big learning curve that we went through.

Finally, the ship was ready.

Launch day came on 10 April 1981. Came, and went, without a launch. The launch was scrubbed because of a synchronization error in the orbit – er’s computer systems. “The vehicle is so complicated, I fully anticipated that we would go through many, many countdowns before we ever got off,” Crippen recalled. “When it came down to this particular computer problem, though, I was really surprised, because that was the area I was supposed to know, and I had never seen this happen; never heard of it happening.”

Young and Crippen were strapped in the vehicle, lying on their backs, for a total of six hours. “We climbed out, and I said, ‘Well, this is liable to take months to get corrected,’ because I didn’t know what it was. I’d never seen it,” Crippen said. “It was so unusual and the software so critical to us. But we had, again, a number of people that were working very diligently on it.”

The problem was being addressed in the Shuttle Avionics Integration Laboratory, which was used to test the flight software of every Space Shuttle flight before the software was actually loaded onto the vehicle. Astronaut Mike Hawley was one of many who were working on solving the problem and getting the first shuttle launch underway. “We at sail had the job of trying to replicate what had happened on the orbiter, and I was assigned to that,” Hawley explained. “What happened when they activated the backup flight software, . . . it wasn’t talking properly with the primary software, and everybody assumed initially that there was a problem with the backup software. But it wasn’t. It was actually a problem with the primary software.”

When the software activates, he explained, it captures the time reference from the Pulse Coded Modulation Master Unit. On rare occasions, that can happen in a way that results in a slightly different time base than the one that gets loaded with the backup software. If they don’t have the same time base, they won’t work together properly, and that was what had happened in this case.

So what we had to do was to load the computers over and over and over again to see if we could find out whether we could hit this timing window where the software would grab the wrong time and wouldn’t talk to the backup. I don’t remember the number. It was like 150 times we did it, and then we finally recreated the problem, and we were able to confirm that. So that was nice, because that meant the fix was all you had to do was reload it and just bring it up again. It’s now like doing the old control-alt-delete on your pc. It reboots and then everything’s okay. And that’s what they did.

Crippen said sail concluded that the odds of that same problem occurring again were very slim. This was all sorted out in just one day. “We scrubbed on the tenth, pretty much figured out the problem on the eleventh, and elected to go again on the twelfth.”

Crippen, though, had little faith that the launch would really go on the twelfth. “I thought, ‘Hey, we’ll go out. Something else will go wrong. So we’re going to get lots of exercises at climbing in and out.’ But I was wrong again.”

On 12 April 1981 the crew boarded the vehicle, which in photos looks distinctive today for its white external tank. The white paint was intended to protect the tank from ultraviolet radiation, but it was later determined that the benefits were negligible and the paint was just adding extra weight.

After the second shuttle flight, the paint was no longer used. Doing without it improved the shuttle’s payload capacity by six hundred pounds.

Strapped into the vehicle, the crew began waiting. And then waiting a little bit more. “George Page, a great friend, one of the best launch directors Kennedy Space Center has ever had, really ran a tight control room,” Crippen recalled. “He didn’t allow a bunch of talking going on. He wanted people to focus on their job. In talking prior to going out there, George told John and I, he says, ‘Hey, I want to make sure everybody’s really doing the right thing and focused going into flight. So I may end up putting a hold in that is not required, but just to get everybody calmed down and making sure that they’re focused.’ It turned out that he did that.”

Even after that hold, as the clock continued to tick down, Crippen said, he still was convinced that a problem was going to arise that would delay the launch.

It’s after you pass that point that things really start to come up in the vehicle, and you are looking at more systems, and I said, “Hey, we’re going to find something that’s going to cause us to scrub again. ” So I wasn’t very confident that we were going to go. But we hadn’t run into any problem up to that point, and when . .. I started up the apus, the auxiliary power units, everything was going good. The weather was looking good. About one minute to go, I turned to John. I said, “I think we might really do it, ” and about that time, my heart rate started to go up. . . . We were being recorded, and it was up to about 130. John’s was down about 90. He said he was just too old for his to go any faster. And sure enough, the count came on down, and the main engines started. The solid rockets went off and away we went.

Astronaut Loren Shriver had helped strap the crew members into their seats for launch and then left the pad to find a place to watch. He viewed the event from a roadblock three miles away, the closest point anyone was allowed to be for the launch, where fire trucks waited in case they were needed. “I remember when the thing lifted off, there were a number of things about that first liftoff that truly amazed me,” he said.

One was just the magnitude of steam and clouds, vapor that was being produced by the main engines, the exhaust hitting the sound suppression water, and then the solid rocket boosters were just something else, of course. And then when the sound finally hits you from three miles away, it’s just mind-boggling. Even

|

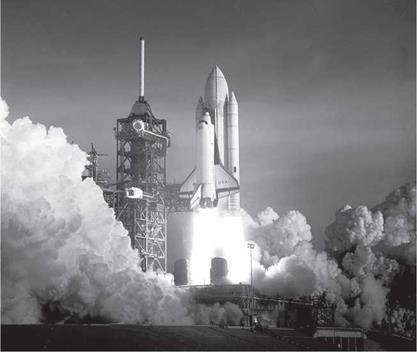

15. The launch of sts-i on 12 April 1981. Courtesy nasa. |

for an experienced fighter pilot, test pilot, it was just amazing to stand through that, because being that close and being on top of the fire truck. . . the pressure waves are basically unattenuated except by that three miles ofdistance. But when it hits your chest, and it was flapping the flight suit against my leg, and it was vibrating, you could feel your legs and your knees buckling a little bit, could feel it in your chest, and I said, “Hmm, this is pretty powerful stuffhere. ”

Crippen had trained with Young for three years, during which time the Gemini and Apollo astronaut imparted to Crippen as best he could what the launch would be like. “He told me about riding on the Gemini and riding on the [Apollo] command module—which he’d done two of each of those—and gave me some sense of what ascent was going to be like, what main engine cutoff was going to be like,” Crippen recalled.

But the shuttle is different than those vehicles. I know when the main engines lit off it was obvious that they had in the cockpit, not only from the instruments, but you could hear and essentially feel the vehicle start to shake a little bit. When the

solids light, there was no doubt we were headed someplace; we were just hoping it was in the right direction. It’s a nice kick in the pants; not violent. The thing that I have likened it to, being a naval aviator, is it’s similar to a catapult shot coming offan aircraft carrier. You really get up and scoot, coming off the pad.

As the vehicle accelerated, the two-man crew felt vibration in the cockpit. “I’ve likened it to driving my pickup down an old country washboard road,” explained Crippen.

It was that kind of shaking, but nothing too dramatic, and it. . . didn’t feel as significant as what I’d heard John talk about on the Saturn V When we got to two minutes into flight, when the SRBs came off that was enlightening, . .. actually you could see the fire [from the separation motors] come over the forward windows. I didn’t know that I was going to see that, but it was there, and it actually put a thin coat across the windows that sort of obscured the view a little bit, but not bad. But the main thing, when they came off it had been noisy. We had been experiencing three gs, or three times the weight of gravity, and all of a sudden it was almost like there was no acceleration, and it got very quiet. . . . I thought for sure all the engines had quit. Rapidly checked my instruments, and they said no, we were still going. It was a big, dramatic thing, for me, at least. . . . You’re up above most of the atmosphere, and it was just a very dramatic thing for me. It will always stick out [in my memory].

The engines throttled, like they were supposed to, and then, at eight and a half minutes after launch, it was time for месо, or main engine cutoff. Crippen described the first launch of the nation’s new Space Transportation System as quite a ride. “Eight and a half minutes from sitting on the pad to going 17,500 miles an hour is a ride like no other. It was a great experience.”

Many astronauts over the years have commented just how much an actual shuttle launch is like the countless simulations they go through to prepare for the real thing. They have Young and Crippen to thank, in part, for the verisimilitude of the sims. Before they flew, there had been no “real thing” version on which to base the training, and when they returned, they brought back new insight to add to the fairly realistic “best-guess” version they had trained on. “I [went] back to the simulations,” Crippen said.

We did change the motion-based, . . . to make it seem like a little bit more of a kick when you lifted off. We did make the separation boosters coming over the windscreen; we put that in the visual so that was there. We changed the shaking on that first stage somewhat so that it was at least more true to what the real flight was like. . . . After we got the main engine cutoff and the reaction control jets started firing, we changed that noise to make sure it got everybody’s attention so that they wouldn’t be surprised by that.

With the main engine cutoff, Columbia had made it successfully into orbit. The duo was strapped so tightly into their seats they didn’t feel the effects of microgravity right away. But then the checklists started to float around, and even though the ground crews had worked very hard to deliver a pristinely clean cockpit, small debris started to float around too.

Now the next phase of the mission began. On future missions, nominal operations of the spacecraft would be almost taken for granted during the orbital phase of the mission. On STS-1, to a very real extent, the nominal operations of the spacecraft were the focus of the mission. “On those initial flights, including the first one, we only had two people on board, and there was a lot to do,” Crippen said.

We didn’t have any payloads, except for instrumentation to look at all of the vehicle. So we were primarily going through what I would call nominal things for a flight, but they were being done for the first time, which is the way a test flight would be done. First you want to make sure that the solids would do their thing, that the main engines would run, and that the tank would come off properly, and that you could light off the orbital maneuvering engines as planned; that the payload bay doors would function properly; that you could align the inertial measuring units; the star trackers would work; the environmental control system, the Freon loops, would all function. So John and I, we were pretty busy. The old “one-armedpaper hanger" thing is appropriate in this case. But we did find a little time to look out the windows, too.

For Young, it was his fifth launch into space—or technically, sixth, counting his space launch from the surface of the moon during Apollo 16. For Crippen, it was his first, and the experience of being in the weightlessness of orbit was a new one. “We knew people had a potential for space sickness, because that had occurred earlier, and the docs made me take some medication before liftoff just in case,” he said. “I was very sensitive when we got on orbit as to how I would move around. I didn’t want to move my head too fast. I didn’t want to get flipped upside down in the cockpit. So I was moving, I guess, very slowly.”

Moving deliberately, Crippen eased to the rear of the flight deck to open up the payload bay doors. Other than the weightlessness, Crippen said, the work he was doing seemed very much like it had during training. “I said, ‘You know, this feels like every time I’ve done it in the simulator, except my feet aren’t on the floor.’ . . . The simulations were very good. So I went ahead and did the procedure on the doors. Unlatched the latches; that worked great. Opened up the first door, and at that time I saw, back on the Orbital Maneuvering System’s pods that hold those engines, that there were some squares back there where obviously the tiles were gone. They were dark instead of being white.”

The tiles, of course, were part of the shuttle’s thermal protection system, which buffers it against the potentially lethal heat of reentry. While the discovery that some tiles were missing was an obvious source of concern for some, Crippen said he wasn’t among them.

I went ahead and completed opening the doors, and when we got ground contact. . . we told the ground, “Hey, there’s some tile missing back there," and we gave them some TV views of the tiles that were missing. Personally, that didn’t cause me any great concern, because I knew that all the critical tiles, the ones primarily on the bottom, we’d gone through and done a pull test with a little device to make sure that they were snugly adhered to the vehicle. Some of them we hadn’t done, and that included the ones back on the omspods, and we didn’t do them because those were primarily there for reusability, and the worst that would probably happen was we’d get a little heat damage back there from it.

The concern on the ground, however, dealt with what else the loss of those tiles might mean. If thermal protection had come off of the oms pods, could tiles have also been lost in a more dangerous area—the underside of the orbiter, which the crew couldn’t see? Crippen said that he and Young chose not to worry about the issue since, if there was a problem, there was nothing they could do about it at that point.

As the “capsule communicator,” or CapCom (a name that dates back to the capsules used for previous NASA manned missions), for the flight, astronaut Terry Hart was the liaison in Mission Control between the crew and the flight director and so was in the middle of the discussions about the tile situation. “Here were some tiles missing on the top of the oms pods, the engine pods in the back, which immediately raised a concern,” Hart said.

Was there something underneath missing, too? Of course, we’d had all these problems during the preparation, with the tiles coming offduring ferry flights and so forth, and the concern was real. I think they found some pieces of tiles in the flame trench [under the launchpad] after launch as well, so there was kind of a tone of concern at the time, not knowing what kind ofcondition the bottom of the shuttle was in, and we had no way to do an inspection. . . . All of a sudden the word kind ofstarted buzzing around Mission Control that we don’t have to worry anymore. So we all said, “Why don’t we have to worry anymore?” “Can’t tell you. You don’t have to worry anymore. ” So about an hour later, Gene Kranz walked in and he had these pictures of the bottom of the shuttle. It was, “How did you get those?” He said, “I cant tell you. ” But we could see that the shuttle was fine, so then we all relaxed a little bit and knew that it was going to come back just fine, which it did.

Hart said that the mystery was revealed for him many years later, after the loss of Columbia in 2003, explaining that it came out that national defense satellites were able to image the shuttles in orbit.

Despite Crippen’s concerns about space sickness that caused him to be more deliberate during the door-opening procedure, he said that the issue proved not to be a problem for him. “I was worried about potentially being sick, and it came time after we did the doors to go get out of our launch escape suits, the big garments we were wearing for launch. I went first and went down to the mid-deck of the vehicle and started to unzip and climb out of it, and I was tumbling every which way and slipped out of my suit and concluded, ‘Hey, if I just went and tumbled this way and tumbled that way, and my tummy still felt good, then I didn’t have to worry about getting sick, thank goodness.’”

In fact, Crippen found weightlessness to be rather agreeable.

This vehicle was big enough, not like the [Apollo] command modules or the Gemini or Mercury, that you could move around quite a bit. Not as big as Skylab, but you could take advantage ofbeing weightless, and it was delightful. It was a truly unique experience, learning to move around. I found out that it’s always good to take your boots off?—which I had taken mine off when I came out of the seat— because people, when they get out and then being weightless for the first time, they tend to flail their feet a little bit like they were trying to swim or something. So I made sure on all my crews after that, they know that no boots, no kicking.

A few of the issues encountered on Columbia’s maiden voyage were problems with the bathroom and trying several times to access a panel that, unbeknownst to the crew, had been essentially glued shut by one of the ground crew. However, there were plenty of things that went well. One of those, Crippen said, was the food, which was derived from the food used during Skylab missions. “We even had steak. It was irradiated so that you could set it on the shelf for a couple of years, open it up, and it was just like it had come off the grill. It was great. We had great food, from my perspective.”

sts-1 was, in and of itself, a historic event, but another historic event around the same time would have an impact on a key moment of the flight, Crippen recalled.

There was an established tradition of the president talking to astronauts on historic spaceflights, and the first flight of the new vehicle and the first American manned spaceflight in almost six years ordinarily would have been no exception. But, in that regard, the timing of sts-1 was anything but ordinary. President Reagan was shot two weeks prior to our flight, so. . . the vice president called, as opposed to the president. The vice president, [George H. W] Bush, had also come to visit us at the Cape. It was sometime prior to flight, but we had him up in the cockpit of Columbia and looked around, went out jogging a few miles with him. So we felt like we had a personal rapport with him, and so when we got a call from the vice president, it was like talking to an old friend.

The launch had been successful; the orbital phase had been successful, demonstrating that the vehicle functioned properly while in space; and now one more major thing remained to be proven: that what had gone up could safely come back down. “That was also one of these test objectives, to make sure that we could deorbit properly,” Crippen said.

We did our deorbit burn on the dark side of the Earth and started falling into the Earth’s atmosphere. It was still dark when we started to pick up outside the window; it turned this pretty color of pink. It wasn’t a big fiery kind of a thing like they had with the command modules;.. . they used the ablative heat shield. It was just a bunch of little angry ions out there that were proving that it was kind of warm outside, on the order of three thousand degrees out the front window. But it was pretty. It was kind of like you were flying down a neon tube, about that color of pink that you might see in a neon tube.

At that point in the reentry, the autopilot was on and things were going well, according to Crippen. He said that Young had been concerned with how the vehicle would handle the S-turns deeper into the atmosphere and took over from the autopilot when the orbiter had slowed to about Mach 7, the first of a few times he switched back and forth between autopilot and manual control, until taking over manually for good at Mach 1. At the time of the first switch, the crew was out of contact with Mission Control. “We had a good period there where we couldn’t talk to the ground because there were no ground stations,” Crippen explained. “So I think the ground was pretty happy the first time we reported in to them that we were still there, coming down.”

Astronaut Hank Hartsfield recalled those moments of silence from the perspective of someone on the ground. “It was an exciting time for me when we flew that first flight, watching that and seeing whether we was going to get it back or not,” he said. “Of course, we didn’t have comm all the way, and so once they went Los [loss of signal] in entry was a real nervous time to see if somebody was going to talk to you on the other side. It was really great when John greeted us over the radio when they came out of the blackout.”

Continued Crippen,

I deployed the air data probes around Mach 5, and we started to pick up air data. We started to pick up TA cans [Tactical Air Control and Navigation systems] to use to update our navigation system, and we could see the coast of California. We came in over the San Joaquin Valley, which I’d flown over many times, and I could see Tehachapi, which is the little pass between San Joaquin and the Mojave Desert. You could see Edwards, and you could look out and see Three Sisters, which are three dry lake beds out there. It was just like I was coming home. I’d been there lots of times. I did remark over the radio that, “What a way to come to California," because it was a bit different than all of my previous trips there.

Young flew the shuttle over Edwards Air Force Base and started to line up for landing on Lake Bed 22. Crippen recalled,

My primary job was to get the landing gear down, which I did, and John did a beautiful job of touching down. The vehicle had more lift or less drag

|

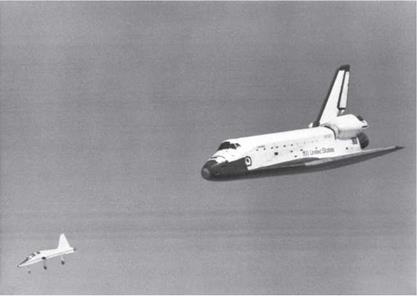

i6. The Space Shuttle Columbia glides in for landing at the conclusion of sts-1. Courtesy nasa. |

than we had predicted, so we floated for a longer period than what we’d expected, which was one of the reasons we were using the lake bed. But John greased it on.

Jon McBride was our chase pilot in the T-38. I remember him saying, “Welcome home, Skipper, ” talking to John. After we touched down, John was. . . feeling good. Joe Allen was the CapCom at the time, and John said, “Want me to take it up into the hangar, Joe?”Because it was rolling nice. He wasn’t using the brakes very much. Then we got stopped. You hardly ever see John excited. He has such a calm demeanor. But he was excited in the cockpit.

On the ground, the crew still had a number of tasks to complete and was to stay in the orbiter cockpit until the support crew was on board. “John unstrapped, climbed down the ladder to the mid-deck, climbed back up again, climbed back down again,” recalled Crippen.

He couldn’t sit still, and I thought he was going to open up the hatch before the ground did, and of course, they wanted to go around and sniff the vehicle and make sure that there weren’t any bad fumes around there so you wouldn’t inhale them. But they finally opened up the hatch, and John popped out. Meanwhile I’m still up there, doing my job, but I will never forget how excited John was. I

completed my task and went out and joined him awhile later, but he was that excited all the way home on the flight to Houston, too.

Crippen’s additional work after Young left the orbiter meant that the pilot had the vehicle to himself for a brief time, and he said that those postflight moments alone with Columbia were another memory that he would always treasure.

CapCom Joe Allen recalled the reaction in Mission Control to the successful completion of the mission.

When the wheels stopped, I was very excited and very relieved. . . . I do remember that Donald R. Puddy, who was the entry flight director, said, “All controllers, you have fifteen seconds for unmitigated jubilation, and then let’s get this flight vehicle safe," because we had a lot of systems to turn down. So people yelled and cheered for fifteen seconds, and then he called, “Time’s up. " Very typical Don Puddy. No nonsense. . . . Other images that come into my head, the people there that went out in the vans to meet the orbiter wear very strange looking protective garments to keep nasty propellants that a Space Shuttle could be leaking from harming the individuals. These ground crew technicians look more like astronauts than the astronauts themselves. Then the astronauts step out and in those days, they were wearing normal blue flight suits. They looked like people, but the technicians around them looked like the astronauts, which I always thought was rather amusing.

Terry Hart was CapCom during the launch of sts-1, but he said watching the landing overshadowed his launch experience. The landing was on his day off and he had no official duties, yet he watched from the communications desk inside Mission Control. “When the shuttle came down to land, I had tears in my eyes,” said Hart. “It was just so emotional. On launch, typically you’re just focused on what you have to do and everything, but to watch the Columbia come in and land like that, it was really beautiful and it was kind of like a highlight. Even though I wasn’t really involved, I could actually enjoy the moment more by being a spectator.”

Astronaut John Fabian recalled thinking during the landing of that first mission just how risky it was.

The risk of launch is going to be there regardless of what vehicle you’re launching, and the shuttle has some unique problems; there’s no question about that. But this is the first time; we’ve never flown this thing back into the atmosphere. We don’t have any end-to-end test on those tiles. The guidance system has only been simulated; it’s never really flown a reentry. And this is really hairy stuff that’s going on out there. And the feeling of elation when that thing came back in and looked good—the landing I never worried about, these guys practice a thousand landings, but the heat of reentry, it was something that really, really was dangerous.

While the mission was technically over, the duties of the now-famous first crew of the Space Shuttle were far from complete. The two would continue to circle the world, albeit much more slowly and closer to the ground, in a series of public relations trips. “The pr that followed the flight I think was somewhat overwhelming, at least for me,” Crippen said. “John was maybe used to some of it, since he had been through the previous flights. But we went everywhere. We did everything. That sort of comes with the territory. I don’t think most of the astronauts sign up for the fame aspect of it.”

In particular, he recalled attending a conference hosted by ABC television in Los Angeles very shortly after the flight.

All ofa sudden, they did this grandiose announcement, and you would have thought that a couple of big heroes or something were walking out. They were showing all this stuff, and they introduced John. We walk out, and there’s two thousand people out there, and they’re all standing up and applauding. It was overwhelming.

We got to go see a lot of places around the world. Did Europe. Got to go to Australia; neat place. In fact, I had sort of cheated on that. I kept a tape of “Waltzing Matilda" and played it as we were coming over one of the Australian ground stations, just hoping that maybe somebody would give us an invite to go to Australia, since I’d never been there. But that was fun.

Prior to STS-i, Crippen recalled, the country’s morale was not very high. “We’d essentially lost the Vietnam War. We had the hostages held in Iran. The president had just been shot. I think people were wondering whether we could do anything right. [sts-i] was truly a morale booster for the United States. . . . It was obvious that it was a big deal. It was a big deal to the military in the United States, because we planned to use the vehicle to fly military payloads. It was something that was important.”

Crippen said STS-i and the nation’s return to human spaceflight provided a positive rallying point for the American people at the time, and human space exploration continues to have that effect for many today. “A great many of the people in the United States still believe in the space program,” he said. “Some think it’s too expensive. Perspective-wise, it’s not that expensive, but I believe that most of the people that have come in contact with the space program come away with a very positive feeling. Sometimes, if they have only seen it on Tv, maybe they don’t really understand it, and there are some negative vibes out there from some individuals, but most people, certainly the majority, I think, think that we’re doing something right, and it’s something that we should be doing, something that’s for the future, something that’s for the future of the United States and mankind.”