TFNG

By 1976 NASA’s astronaut corps had seen a large number of departures. Many of the early astronauts who had joined the agency as pioneers of spaceflight or as part of the race for the moon felt like they had accomplished what they had come to do. The last Saturn to fly launched in 1975, the next opportunity to fly was still years away, and some in the corps decided they had no desire to wait.

Only one of the Original Seven astronauts, Deke Slayton, remained in the agency, as did only one member of the second group, John Young. Two members each remained of the third and fourth groups (although only one of those four astronauts would get the opportunity to fly on the shuttle). The fifth group was better represented—eight of the Original Nineteen were still at nasa—and the majority of the sixth group and all of the seventh were still at the agency, having arrived in the corps too late to be assigned Apollo flights.

With the number of astronauts dwindling, the ambitious plans for the shuttle program required new blood. So in 1976 NASA announced for the first time in a decade that it would be accepting applications for a new class of astronauts, to support the Space Shuttle program.

Astronaut Fred Gregory saw the ad for Space Shuttle astronauts on television. “I was a Star Trek freak, and the communications officer, Lieutenant Uhura, Nichelle Nichols, showed up on Tv in a blue flight suit,” Gregory said. “As I recall, there was a 747 in NASA colors behind her; you could hear it. But she pointed at me and she said, ‘I want you to join the astronaut program.’ So, shoot, if Lieutenant Uhura looks at me and tells me that, that got me thinking about it.”

Steven Hawley saw the NASA announcement on a job openings bulletin board while in graduate school at the University of California.

I remember there was this letterhead that said NASA on it, and I thought, “Wow, that’d be interesting. ” I looked at it, and it said they were looking for astronauts.

I had no idea how they’d go about hiring astronauts, and here’s an announcement saying, hey, you want to be an astronaut, here are the qualifications. You have to be between five foot and six foot four, and you have to have good eyesight, and you have to have a college degree, and graduate school counts as experience. You need three years of experience, and I’m thinking, “Well, I’m qualified. " I’ve also told kids that so were twenty million other guys.

Hawley recalled that this was the first time he thought that becoming an astronaut might really be possible for him, because of changes in the selection criteria. “I probably dropped everything I was doing at that moment and set about filling out this application to become an astronaut. I didn’t realize till years later that it’s actually the same application you fill out to be any government employee, SF-171. You fill it out and send it in. I even remember sending it by, I think, return receipt request so that I could make sure that this thing got into the hands of the proper people at NASA.”

Realistically, Hawley said, he didn’t think he would be selected. He realized the pool contained many well-qualified applicants. But even with what he believed were slim odds, he applied anyway. “Why in the world would they pick me?” he said.

I still think perhaps they didn’t mean to, and one day they’ll come and tap me on the shoulder and say, “Excuse me. You’ve got this guy’s desk, coincidentally named Steve Hawley, and he’s the one we meant." I’ve told kids this, too, that the reason I applied, as much as anything, was because I knew that if I applied and didn’t get picked, and then I watched shuttles launch with people on them and building space stations and putting up telescopes in space, I could live with that, if NASA said, “Well, thanks, but you’re not what we’re looking for." But to not apply, to not try, and then wonder your whole life, could you have done it if you had tried, I didn’t think I could take that. So it was okay if they said no, but I didn’t want to go through the rest of my life wondering, had I only tried, would I be able to do it?

Before 1978 NASA had selected five groups of pilots and two groups of scientist-astronauts. The eighth group would be the first mixed class, including both pilots and a new designation, mission specialists.

The new designation was of particular interest to Mike Mullane, who at the time was a flight-test weapon system operator for the air force. “nasa announced they were selecting mission specialist astronauts, and this was the new thing, because now you didn’t have to be a pilot to apply to be an astronaut. So this dream of perhaps being an astronaut was now back open to me. In fact, I remember that night that they announced it. This was big news at Edwards, because virtually everybody at Edwards Air Force Base wanted to apply to be an astronaut.”

The new class would be the largest group of astronauts yet. More than eight thousand applications were received. In 1978 NASA announced the first class of shuttle astronauts, dubbed TFNG, an acronym given multiple meanings, most politely, “thirty-five new guys.”

Among the new class were, of course, test pilots from the navy and the air force, many of whom knew each other and had trained and served together. Rick Hauck was on his second cruise as a navy pilot on the uss Enterprise when the announcement came out. “There was a flyer from NASA saying they were looking for applicants for the astronaut program to fly the shuttle and, in fact, four of us on the Enterprise wound up in my astronaut class: myself, Hoot Gibson, Dale Gardner, and John Creighton. Three of the fifteen pilots were from that air wing. Dale Gardner was a mission specialist. Which is really kind of interesting, three of fifteen. What’s that? Twenty percent came from that ship.”

Hauck didn’t grow up with an interest in space, and as a child there had been no space program for him to aspire to. “The word Apollo didn’t even exist in terms of spaceflight when I was thinking about becoming a naval aviator,” said Hauck, who was a junior in college when Alan Shepard made his first spaceflight in 1961. “Even before I became an aviator, while I was at [The U. S. Naval Test Pilot School in] Monterey, I had read that NASA was recruiting scientists to become astronauts, and I wrote a letter to NASA saying, ‘I’m in graduate school. You could tailor my education however you saw fit to optimize my benefit to the program, and I’d be very interested in becoming an astronaut.’ I got a letter back saying, ‘Thank you very much for your interest. Don’t call us. We’ll call you.’ That was in early ’65, I think, so it was twelve years later that I was accepted into the astronaut program.”

Sally Ride, the United States’ first female astronaut to fly in space, saw the ad for a new class of astronauts in the Stanford University newspaper, placed there by the Center for Research on Women at Stanford. “The ad

|

8. Astronauts training to experience weightlessness on board the nasa кс-135. Courtesy nasa. |

made it clear that nasa was looking for scientists and engineers, and it also made it clear that they were going to accept women into the astronaut corps. They wanted applications from women, which is presumably the reason the Center for Research on Women was contacted and the reason that they offered to place the ad in the Stanford student newspaper.”

Another member of the eighth class, air force pilot Dick Covey, got to nasa by studying and following a career path similar to those of the early astronauts. “As I looked at what it looked like those original astronauts had done. . . that became a path for me to follow,” Covey said. He majored in astronautical engineering and participated in a cooperative master’s program between the Air Force Academy and Purdue University. According to Covey, fifteen of the selected Thirty-Five New Guys participated in the program at the same time as he.

We gave up our graduation vacation time. All my [other] classmates got two months to go off and party and tour the world and do whatever and then go to their flight training, while we all went immediately, right after graduation to Purdue and started school again. But in January following graduation in June, we all had our master’s degree in aeronautics and astronautics, and those of us that were going to flight training already had our flight-training date, and we went immediately to flight training. So, for someone that wanted to be an astronaut, being able to go through the Air Force Academy, major in astronauti – cal engineering, and get a master’s degree from Purdue in aeronautics and astronautics within seven months and then go immediately to flight training was an extraordinary opportunity. I often wonder, if I had not done that, whether I would have ever become an astronaut. . . . One of the reasons Purdue has so many astronauts is there’s all these Air Force Academy guys who went through that program over time, and it added to their numbers then.

When the announcement was made, Covey applied through the air force. The air force had decided, as the other services did, that it would have its own selection of those it would nominate to nasa, and Covey was selected as one of the air force’s applicants.

Hauck and Dan Brandenstein were test pilot school classmates and squadron mates six years prior to their selection to the corps. Hauck said the two talked a lot back then about whether or not they would apply to the astronaut program.

Part of the preinterview process was the folks in Houston took each folder. Some ofthe people were rejected immediately. Some, they said, “Well, let’s find out more about this person. ” They make a lot of phone calls. “Hey, do you know Rick?” or, “Do you know Dan? What do you think about him?” So I got a call one day in my office at Whidbey Island, Washington, and it was John Young. And John said, “I’m on the selection board for this astronaut program. ” He didn’t say anything about knowing that I was applying. He said, “Dan Brandenstein, he’s in your squadron there. What do you think about him?” And I told him, I said, “I think he’s a great guy. He’d be a super astronaut. ” He said, “Okay, thank you very much. ” And I said, “Excuse me, but I’m applying also. ” He said, “I know. I know. Thank you very much. ”

Covey said that his selection as one of the air force’s candidates for the new class of astronauts was the first of a series of milestones that made the possibility of achieving his goal seem a little more real. “When they started [interviewing candidates] we knew they were doing it,” Covey said, recalling that, at the same time, nasa was conducting glide-flight tests of the prototype orbiter, Enterprise.

So everybody’s getting excited about the shuttle now. . . . We knew that NASA was getting ready. I had a vacation planned. I had just taken my wife and kids and put them on an airplane. They were on their way to California, and I was supposed to join them within a day or two. I got a call, and it was from Jay Honeycutt. Jay was calling to invite me to come to Houston. . . . It was very short notice for an interview. That was the first day they were calling anybody. Finally had got their list down and alphabetically they started calling people to come. I’m sitting there. I just sent my wife out. I’m supposed to go join her on this vacation out here. I remember thinking—I mean, this was the hardest question I was going to ask. I said, “Jay, so if I said I couldn’t come next week, will you invite me back another time?”I later talked to Jay, and he said that he said, “Well, just a second. Let me check. ” So I go, “Oh, no. ”

Covey said that Honeycutt told him later that he had to go ask whether they could schedule another time for a candidate, since it was a possibility that hadn’t been discussed. “They expect that everybody will say, ‘I’ll be there tomorrow,’ you know. So he came back and says, ‘Yeah, we’ll invite you back.’ Well, so I go on my vacation, and I’m going, ‘Oh, my God. They haven’t called me yet. When are they going to call me?’ So it was a terrible vacation. It was a terrible vacation. Toward the end of it they finally called; said, ‘Well, we’re getting our stuff together. We want you to come week after next.’”

The interview process lasted a week and included physical, psychiatric, and psychological exams. “The physical exams included lab work of everything that they could measure,” recalled Hauck. The psychiatric exam, Hauck said, involved interviews with a “good-guy psychiatrist” and a “bad – guy psychiatrist,” each of whom played a different role in the test.

The bad-guy psychiatrist evaluated how you did under pressure. For example, “I’m going to read off a list of numbers. Tell me what they are in inverse order. ” And you start with two, five, and you say, “Five, two. ” And then three numbers, then four numbers, then five, then six, and you’re sitting there just thinking, “I cant do this. ” At some point, you make a mistake. Inevitably, at some point you make a mistake and the psychiatrist said, “That’s wrong, ” with a scowl on his face. “Cant you do better than that?” Blah, blah, blah. And, of course, he doesn’t care whether you did it with five numbers, three numbers, or eight numbers. He’s more interested in seeing whether you get flustered, wheth –

eryou get antagonistic. And as I recall, I might have said, “That’s the best I can do, yes.” “That’s okay.”

The role of the other interviewer, Hauck said, focused more on the candidate’s emotions and interpersonal relationship styles. “The good-guy psychiatrist would ask you questions such as if you were to wear a T-shirt and there were an animal on the front of the T-shirt and you wanted that to sort of be your symbol, what would that animal be? I forget what I said, and I’m sure he drew some conclusions whether you said a tiger or a turtle or a rat or what.”

In another part of the test, he said, candidates were zipped up individually into a fabric sphere.

In order to get into it, you had to get into a fetal position, into a ball, and the concept of the sphere was it was just small enough so that it could go through the crew hatch in the Space Shuttle in the event that you had to rescue people from one shuttle to another. The charter was, “Were going to put you in this. You have oxygen. You have communications. Were not going to tell you how longyou’re going to be in there. At the end, we want you to write a flight report on what you think are the upsides, downsides, what more needs to be studied for this concept. ”

So that was fascinating. There was really two objectives there. One is, see how analytical you are about analyzing.. . a piece ofhardware or software. Number two is a claustrophobia test, because you literally couldn’t move very much, and it would be very clear ifyou had claustrophobic tendencies. As I recall, I found it most comfortable to sort of lie on my back with my knees up, and I almost fell asleep.

The “big deal” of the process, Hauck said, was the board interview with Johnson Space Center officials who made the selection decisions.

They’d say, “Tell us about yourself,” and just let you talk. I don’t remember getting any surprise questions, but some of the people got surprise questions. For example, President Carter was president at the time. He had just signed the bill that transferred the Panama Canal back to Panama, and one of the questions was, “What do you think about the Suez Canal situation?” And of course, the person might have started commenting about the Panama Canal because that was what was in the news, and then one of the board members might say, “Why are you telling us about the Panama Canal? We asked you about the Suez Canal. ” And again, it’s an opportunity to see how people react under some level of stress and so on.

Interviewees were called to Houston in groups. John Fabian said his group comprised about twenty-two people, and he was convinced that any of them would have made fine astronauts. “It was all rather intimidating and awe-inspiring,” Fabian said, “but somehow, at the end of it, some people got lucky, and other people didn’t, and I was one of the lucky ones.”

At six feet one, Fabian was too tall for earlier astronaut selections, but with the Space Shuttle program came a new maximum height of six feet four. Before that, he’d not given it much thought, he said. “I’ve always had the philosophy that you shouldn’t try to be something you can’t. I couldn’t be an astronaut if I was six foot one, and that was above the height limit.”

The highlight of the interview week for Terry Hart was the selection committee, led by Director of Flight Operations George Abbey, in part due to an unusual circumstance in another part of the interview. Hart’s blood tests early in the week were flagged for being outside the parameters for uric acid.

“The basic message I was getting was that that was going to be disqualifying,” Hart said.

And in a sense I think that really helped me, because I went into the interview just [like] I was down here for the experience and everything. I was relatively relaxed as you could be for such an interview and went through that interview process and finished the week up. I went home and told my wife that it was a wonderful experience, but I wasn’t going to make it, which is what I thought from the beginning. But I was a little disappointed at that point, because as you get into the process, your competitive juices start flowing and everything. You really want to be part of this very exciting adventure that was about to begin. Yet realistically, I’d met all these people that… seemed to be so much more qualified than I was.

On the flip side, Norm Thagard found himself feeling like he was in the hot seat during his interview, particularly over a comment he made about women.

You sit there at a table and there are people on all sides of you during the interview and they’re firing questions at you. . . . The question George [Abbey] asked me was, “Well, I see that you made a C in ballroom dancing. Why was that?" I said, “Well, our instructor was a woman who liked to lead." Which was true. “I found that very difficult to learn to dance with someone who was leading." But then the next question was, “Well, what do you have against women?" And, you know, they’re firing these questions from all over and you’re turning

this way and then you’re turning that way. [I heard] a little ruffle of movement and I see someone get up and leave. When I turn back, Carolyn Hunt – oon, who was the only female member on the thing, had gotten up and left. I said, “Well, this is just great." First of all, they’ve drawn this thing out, which to me, I thought was an innocent enough response, but now they’re making a big deal out of it. Now this woman is obviously a feminist and offended that I’ve said this, and so she’s left.

After the selection announcement, Thagard would find out what had happened when he and the other new astronauts were brought to Johnson Space Center for media events. “Carolyn Huntoon was the one that babysat our kids, because we brought them along for that,” he said. “She took us in our car over to some of the events at jsc. I reminded Carolyn that she had gotten up and left during my interview and what I had thought was the reason why. She says, ‘Oh, no, I had to get up to leave because my babysitter had to go home.’ So it took me a long time to realize that, in fact, it hadn’t been all that bad.”

After the week-long interviews, it was time to wait. And wait. And wait. “I think I was [at Johnson for the interview] in August or something,” Covey recalled. “And so it was go home and wait for five months to see what happened. And nothing; there was nothing. It was real quiet during that time period.”

Finally, in January 1978 the phone calls started going out. John Fabian remembers where he was when he first heard that the new class had been selected, before he knew whether he had been chosen or not. “I was in bed that morning when my wife and I heard an announcement that NASA had selected thirty-five astronauts and among this group there would be six women,” he said. “And my wife said, ‘That’s too many,’ which sounds funny today. But, of course, her concern was that, if there are six women selected, that’s six slots that my husband isn’t going to fill.”

It wasn’t until later that day at work that Fabian got the phone call from nasa as he was preparing to go teach a class. “Mr. Abbey was on the other end, and he said, ‘John, this is George Abbey; I’m calling from the Johnson Space Center. I’m interested to know if you’re still interested in becoming an astronaut.’ I said, ‘Yes, I certainly am.’ He said, ‘Well then, I’m pleased to tell you that your name is on this list.’ So I had to have somebody else go teach my class, because I was psychologically not prepared to go lecture at that particular time. It was a great thrill, a real honor.”

At the time Mike Mullane got his phone call, he was stationed at Eglin Air Force Base in Florida but was on temporary duty to Mountain Home Air Force Base in Idaho. Mullane was phoned by his wife, who told him George Abbey had called their home to talk to him. Like several others, Mullane was aware the selection had been made because he had heard on the news about the women who were selected. Finally, he talked with Abbey himself and got the official word that he had been chosen. “I just went out and screamed with joy. I remember that night I bought some beer for the rest of the people that I was working with there at Mountain Home in the hangar there, and we had a little party. I remember. . . stopping out in the desert. This is out in Idaho. It’s like New Mexico. Go out in the desert; it’s like being in space. Black sky. I remember standing out there and just looking at the sky and thinking that I had this chance of actually flying in space.”

Mullane said that, despite the news of his selection and that moment in the desert, he still had doubts that he would ever actually make it into orbit.

I’m one of these guys that tend to think of all the things that can go wrong, like a medical problem or the rocket blows up or whatever it is. . . . Even though Abbey called and told me that I’m an astronaut, I felt like there’s still a lot that could go wrong that would prevent me from actually flying in space, but I still had this overwhelming sense of joy that I had this shot at getting into space. It was a lifetime dream come true to be an astronaut. But again, I didn’t really ever consider myself an astronaut until the srbs ignited on my first mission. All the rest of it I just thought it was name only. But it certainly was an overwhelming, joyful experience of the first magnitude.

We tend to set these goals and think that once we reach this goal, it’s going to make you happy for the rest of your life. . . . Of course, that never happens. I remember telling my wife that if I just flew one time in space, just one time in space, that’s all that I would need to be infinitely happy. And then I’ll bet within two days after landing from my first mission, I said, “I sure would like another mission. ” It’s just one of those things. It’s a joyful experience to be told that you’re going to get a shot at riding into space. So I was weightless at that point, I think. I was just floating around, already weightless.

Norm Thagard also had the yo-yo experience of assuming that finding out about the selection on the news meant that he hadn’t been picked, only to get the phone call the next day at work from George Abbey saying that he had been chosen.

I hung up the phone and turned to the group that was there and said, “I guess I’m an astronaut. "Then I went back in my room and put my head down on the desk and was real depressed for the rest ofthe day. That’s honest. I was depressed. It took me awhile to figure out what was going on, but I finally think I understood that I’d always had goals, I always wanted to do this, that, and the other, but I never had really any goals beyond being an astronaut. So you’re all of a sudden faced [with] there’s nothing left to live for. Then you realize, well, yes, there is, because you still hadn’tflown in space. So life goes on. But my reaction really surprised me at first, because it was depression. I mean, I was not elated at all. I remember feeling, on the one hand, sort ofgratified, but on the other hand, just feeling real down.

The Thirty-Five New Guys were the first class of astronauts to come in as astronaut candidates, or AsCans. “In previous selections they had had some people that didn’t really particularly care for the job and maybe didn’t know what the job entailed and left,” Mike Mullane said. “I think to avoid whatever embarrassment that might cause NASA or the individual, they established this plan which you come in for a couple of years and you go through training and evaluation. Then at the end of that period you either become no longer a candidate, and now you’re an astronaut, or it’s decided either mutually or by one party or the other that, yes, this probably wasn’t the right move, so we agree to part company at this point. No hard feelings.”

Mullane said he was afraid that the new process might mean that he would never earn the official title of astronaut.

I realistically thought there was a chance in a couple of years they might get rid of me. So I was concerned about that. I knew this was going to be an interesting mix of people, and I knew that there were going to be people that knew a lot more about stuff that was important than I knew, and there were going to be these pilots and all that other stuff so I was a little concerned how we would all get along. But I think primarily I was just concerned about would I be able to really do the things that would be expected of me.

This first group of AsCans was so large that its members became the majority of the Astronaut Office when they reported for duty in July 1978. Loren Shriver recalled,

I think the folks who were still in the Astronaut Office, which, of course, had been between programs for several years of that period, were glad to see us there on the one hand, because they were all really busy doing the technical things that astronauts do while they’re waiting to go fly—various inputs to boards and panels and safety inputs and crew displays and all that kind of thing. They were all really busy, and I think they were happy to see us show up so that we would be able to help them and take some of the load. At the same time, I think there was a bit of the “Oh, no, all these new guys. How are we ever going to get them trained and up to speed? Will they ever be ready to go fly in space?” Well, that’s kind ofa natural reaction to the group of people who has been there and done that a lot. That’s a bit ofa different aspect of “We’re happy to have them here, but I don’t know, it’s maybe just a little more work for a while until we get them all checked out. ”

Dick Covey said that the remaining veterans were quite welcoming to the large surge of rookie astronauts. “I never felt like they saw us coming in as ‘Oh, my God, we’ve got more people than we need,’” he said. “I’ve seen that since then, as the Astronaut Office has gone through huge swells and stuff, but I didn’t sense that from them. I got the sense that the twenty something of them that were still in the office were looking forward to some additional help. We seemed to be welcomed very graciously, particularly by the [previous class]. They really embraced our arrival, and I always felt like they felt like they needed more people to do the work for the office and getting ready to fly.”

The warm welcome was also experienced by Rick Hauck, who agreed that the “real astronauts” were grateful for the extra hands.

They’d already started gearing up for shuttle and they needed help. So we were there to be helpful in any way we can. They wanted to get us as smart about the systems as soon as they could. . . . Everyone was very hospitable to us, bending over backwards to make us comfortable and telling us how much they needed us. We felt wanted, and contrast that with Dick Truly and Bob Crippen, [who] had joined from the mol program, the Manned Orbiting Laboratory program, and when they arrived there, I forget whether it was Deke Slayton or someone else said, “We didn’t ask for you. We didn’t want you. Stay out of the way. ” Big difference. So I think that they were even sensitive to that kind ofa reception.

John Fabian said that he had also heard horror stories about how the last class—Group 7—had been treated when the recruits arrived in 1969. Unlike the other classes, Group 7 had not been chosen through an open selection. The air force had formed its own astronaut corps, independent of nasa, to support its Manned Orbiting Laboratory space station program. When that program was canceled, the air force closed its corps and asked nasa to take on its excess astronauts. At the time, nasa’s astronaut corps had more people than it needed for the remaining Apollo-era seats available. There were reportedly multiple attempts at the jsc flight operations level to get rid of the new recruits, which were overruled by nasa leadership, eager to have the air force’s support as the agency sought funding for the Space Shuttle.

“We heard some bad stories about the way the mol guys were treated when they came in, as kind of a leper colony, and we weren’t treated that way at all,” Fabian said. “I think they were glad to see us come. The shuttle program was just around the corner, we thought. It turns out it wasn’t quite just around the corner, but we thought it was, and there was a lot of work to be done, and there was a lot of legwork that needed to be accomplished. . . . So I think they were glad to see us. They got some new hands and legs, and I think that they counted on us being somewhat motivated and somewhat capable. So it was a very pleasant thing.”

Steven Hawley was a little less sure what the veterans thought of his As – Can class.

We hadn’t really been flying a lot in ’78;. . . since we’d landed on the moon, there’d only been like four crews to get to fly, and here’s this new bunch of guys walking in the door. I could see how some of the guys that had been around for a while waiting to fly might have been a little resentful. If they were, that didn’t come across in any way, because our training was separate from what most everybody else was doing. Everybody else was doing mainstream support of shuttle and development of everything that needed to be done before STS-1. We would cross paths at the Monday morning meeting or you’d run into them at the gym or something like that, but mostly we did our own thing.

Initially, Hawley said, the main interaction between the new class and the veteran astronauts came in the form of nasa history lessons during their training. “They thought it was important, and I think it is, that we hear from people that had flown Apollo and had flown Skylab and astp. So I remember we got lectures from some of the guys that were still there, some of the

guys that had left but came back to talk to us about their flights and what

it was like back then. . . . These were my heroes, and to actually get to sit in a room and listen to them talk about their flights was pretty awesome.”

Veteran Apollo astronaut T. K. Mattingly confirmed that the corps was glad for the new class and the needed help it provided.

Once we got these folks on, the OV-101 [Enterprise] was rapidly approaching the time to get ready to go. So we put together the training program for the new folks and helped them get started on that. Then we split them up, .. .just spread amongst the few of us that had been around. [The shuttle’s robot arm] and a lot of these other activities were all getting sort of a lick and a promise instead of real attention till the ’78 group came on board, and once they went to work, then they really took hold and played very key roles in the development.

Of course, the “Thirty-Five New Guys” weren’t just “guys.” The veteran fly – boys of the astronaut corps also welcomed for the first time six women who were part of the new class. Sally Ride pointed out that her class presented a double whammy for those who had already been in the corps—not only were they now outnumbered by rookies, they were the minority in an office that was suddenly much more diverse. “They seemed to accept us pretty well,” recalled Ride.

We had them outnumbered, so I’m not sure they had a choice. It was clearly very different for them. They were used to a particular environment and culture. Most of them were test pilots. There were a few scientists, but most were test pilots. Of course the entire astronaut corps had been male, so they were not used to working with women. And there had been no additions to the astronaut corps in nearly ten years, so even having a large infusion of new blood changed their working environment.

But they knew that this was coming and they’d known it was coming for a couple of years. Well before the announced upcoming opportunity to apply for the astronaut corps, NASA had decided that women were going to be a part of it. So I think that the existing astronauts had a couple of years to adjust and come to terms with it. By the time that we actually arrived, they had adapted to the idea. We really didn’t have any issues with them at all. It was easy to tell, though, that

|

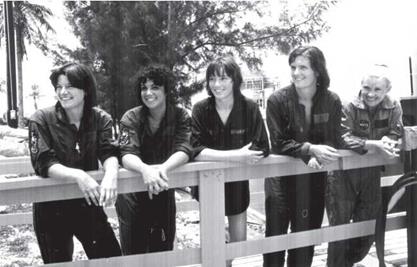

9. The first female astronaut candidates in the U. S. space program, leftto right, are Sally Ride, Judy Resnik, Anna Fisher, Kathryn Sullivan, and Rhea Seddon. Courtesy nasa. |

the males in our group were really pretty comfortable with us, while the astronauts who’d been around for a while were not all as comfortable and didn’t quite know how to react. But they were just fine and didn’t give us a hard time at all.

Ride said there was a lot of media attention surrounding the TFNG announcement since it was the first astronaut selection in ten years and the first selection to include women. She said the attention didn’t affect her private life all that much, since the agency worked to keep the extra attention at a minimum so that it didn’t affect the astronauts’ abilities to train and work. “It wasn’t particularly burdensome after the initial flurry of interviews,” Ride said. “There was a fair amount of [attention], but it was still easy to have a normal life. . . . I think jsc worked hard to prepare for the arrival of women astronauts and female technical professionals. The technical staff at jsc— around four thousand engineers and scientists—was almost entirely male. There was just a very small handful of female scientists and engineers—I think only five or six out of the four thousand. The arrival of the female astronauts suddenly doubled the number of technical women at jsc.”

Joe Engle, who became an astronaut in 1966 as part of the “Needless Nineteen,” recalled that one dilemma with adding women to the corps was figuring out where to put the women’s locker room at the gym. “We just

had a guys’ locker room over there up to then,” Engle said. “So Deke [Slayton] had to figure it out. And of course, good old Deke, he said, ‘Well, hell, we’ll just put a curtain up and you can all use the same damn room,’ but he finally conceded that they would have a separate room.”

For some, this was their first time to ever work closely with women. “It was really all new to me, and I didn’t do it all right, either,” Fabian recalled. “That was a slightly different era. It was an era in which you would take the centerfold of Playboy magazine and post it up on the back of your office door, and that was thought to be totally acceptable as long as it was the back of the door instead of the front of the door. And people hadn’t yet thought of the word ‘harassment.’ We were all learning. We were all learning in those days.”

Mike Mullane said that working with his female classmates was a new experience for him as well. “I’d be a liar if I didn’t say it was difficult to learn how to work with women,” he said,

and not because of the women; because I had no life experience in working with women. I tell everybody, there were two things that at age thirty-two I did that I had never done in my life, when I woke up to go to work for my first morning as an official astronaut at NASA. . . dressed myself, and worked with women.

I went to twelve years of Catholic schools, wore a uniform every day. Woke up, put on a uniform. Went to school. Went to West Point. For four years I don’t think I ever saw an article of civilian clothes. Didn’t have it in the closet. Wore a uniform all the time. Went into the airforce. Would wake up in the morning, go to work, put on a flight suit. Not one time in my life did I ever have to go to a closet, open it up, and pick a pair of slacks and shirt that matched. And that was a real struggle. In fact, a number of times that I walked out of the house or walked through the kitchen on my way to work, Donna, my wife, would look at me and say, “You’re not going to work dressed like that, are you?” In fact, she told me she was going to get Garanimals and put them on the clothes so that I could match the elephants with the elephants and the giraffe with the giraffe.

Mullane said that unfamiliarity with dealing with civilian clothes was a common struggle among the career-military astronauts. “I wasn’t the only one struggling in this regard, because I remember driving up one day to NASA with my kids in the car, . . . and there was one of the astronauts walking around in plaid pants,” he said. “Plaid pants. I mean, even I, with my absolute zero fashion sense, thought that maybe that looked a little bit retro. In fact, to this day, my kids, they’re in their thirties now, if I’m with them and they see a golfer out in plaid pants, my kids will laugh and say, ‘Hey, Dad, check it out. There’s an astronaut.’”

Just as he’d never been in an environment where he didn’t wear a uniform, Mullane said, those environments also limited his contact with the female sex. “I had never in my life ever worked professionally with women,” he said.

In fact, my whole life, the Catholic schools I went to weren’t gender-segregated, but a lot of the classes were. .. . So I had very little interaction with females as a young person, and West Point had no females at the time I was there. In the air force, the flying community that I was in had no females when I was in there. So as a result, I was thirty-two years old when I was selected as an astronaut and I had never worked professionally with women, and I have to admit that I’m sure I was a jerk, in a word, because I just didn’t know how to act around them, telling jokes that probably were not appropriate to tell and just doing dumb things that were inappropriate and probably would have gotten me a prison sentence in this day and age now with sexual harassment and all that. The women had to endure a lot, because there was a lot ofguys like myselfin that regard, I think, that had never worked with women and were kind of struggling to come to grips on working professionally with women, but we all made it. That’s for sure.

The camaraderie among the thirty-five was interesting, too, because of the extreme diversity and the introduction of the new mission specialists. There was a difference even in the aspirations that led each new astronaut to the corps. The TFNG class was announced almost nineteen years after NASA hired its first astronauts, and several of the pilot candidates in Group 8 had spent much of their career with the idea in the back of their minds of someday joining their ranks.

One of those was Dan Brandenstein, who had been interested in becoming an astronaut for a long time and had set himself milestones to accomplish to get there. “But a number of the mission specialists, they weren’t pilots and they never had been pilots. I think Sally Ride is one that comes to mind. I mean, she was saying how she was just walking through the Student Union one day and saw a flyer that said NASA was looking for astronauts, and that’s really the first time she’d ever thought about it. A number of the mission specialists, that was their attitude.”

To Brandenstein, the new diversity his class brought to the astronaut corps was a good thing. Like others, he’d been in much more homogenous environments until then and was excited about having his horizons broadened. “The wide diversity of backgrounds that we had in that class was unique to NASA, and I personally loved it, because I’ve always been interested in a lot of things,” he said.

I’m fascinated going into a factory where they make bubble gum or you name it, just to see how different machines and different things work. In my lifetime, I took up skiing and I didn’t take lessons; I learned to do it through the school of hard knocks. I bought a sailboat and I made some sails because I thought it would be kind of fun to make a sail. So I was always interested in not just what I did, but kind of a wide variety of things. So being now in a group with people that were doctors and scientists and all, this was really fascinating to me.

Mattingly said the new mission specialist category of astronaut required major adjustments that the Astronaut Office pretty much made up as they went along. For example, he said, he was involved in some discussion about who should command the Space Shuttle missions. Up to that point, only four NASA missions had included nonpilot astronauts—four scientist-astronauts had flown over the course of the last moon landing and the three Skylab missions. On those flights, the commander was still chosen from the pilot astronauts in the corps. Mattingly, who said that his experience on aircraft with larger, more diverse crews gave him a different perspective, wondered whether that tradition should change with the new mission specialists.

We came up with these crazy ideas that since we’re going to be flying this “airplane, " but the mission of the airplane is whatever is in the payload bay, maybe the mission commander should be a mission specialist, or maybe the mission commander is a separate position where both pilots and mission specialists aspire to that being the senior position. The skipper of a ship doesn’t put his hands on a steering wheel; he directs the mission. I thought that was really good, and some of my navy buddies, “Yeah, that makes sense." Boy, that did not float at all, and there was a bigger division between mission specialists and pilots than I had ever guessed there would be.

Mattingly intermixed pilots and mission specialists on the teams developing the Shuttle Avionics Integration Laboratory (sail), thinking the designations wouldn’t matter much. “I just mixed them up,” Mattingly recalled.

I said, you know, “Bright people work hard. I don’t care where you go. ” So we sent mission specialists and pilots both to the sail, and the job that you had to do over there didn’t require any aeronautic skills at all; it was checking out the software and just going through procedures. Anybody who was willing to take the time to learn the procedures and has some understanding of how this computer system works is going to be fine.

We ended up having to put out all kinds of brush fires, you know, “He cant do that. He’s a mission specialist. ”. . . We had a sail group around the table when they were having a debriefing. We did this every week to go over all the things we’d done and what was open. Steve [Hawley] started it off with, “Did you hear about the pilot that was so dumb the others noticed?” I’ve told that to a lot of people, and I thought that was great. And at that point I think that Steve finally broke the ice, and everyone kind of said, “This is dumb, isn’t it. ” After that, at least it never came to my attention again if they had any problems, but from then on, they really came together.

Brewster Shaw recalled that early on Kathy Sullivan commented to him that the pilots were going to be just like taxi drivers and that it was the mission specialists who were going to do all the significant work on the Space Shuttle program. “Turns out, by golly, she was pretty much right,” Shaw said. “But at the time, being a macho test pilot, I was a little appalled at her statement.” Shaw saw just how true Sullivan’s statement was as pilot of STS-9, his first mission. “Our role was very minimal, John [Young’s] and mine, because we didn’t have to maneuver the vehicle very much, but we had to monitor the systems a lot. So we didn’t get to participate to a great length in the science that was going on. So, yes, pretty much, we got it up there and we got it back. In the meantime, the other guys did all the work.”

For training the TFNG group was split into two sections—the Red Team and the Blue Team, Brandenstein explained. Teams took turns in the classroom and flying, spending a half day on each activity and then switching off with the other team. “We broke in two parts because the classroom didn’t hold the thirty-five people,” John Fabian recalled, “and so you got to know the people that were in your class much better, in reality, than you got to know the people that were in the other class, particularly in the first three or four months. But what we found out very quickly was that all of these people, whether they were the youngest in the group or the oldest in the group, they were all extraordinarily bright, extraordinarily capable, and very, very eager to succeed in what it was that they were doing.”

The new AsCans brought a variety of interesting backgrounds to the table, according to Brandenstein.

There were a lot of neat people. . . that knew a lot about things I didn’t have a clue about, so you could learn a lot more. And that was kind of the flavor of the training. The first year of training, they try and give everybody some baseline of knowledge that they needed to operate in that office, so we had aerodynamics courses, which, for somebody who had been through a test-pilot school, was kind ofa “ho-hum, been there, done that," but for a medical doctor, I mean, that was something totally new and different. But then the astronomy courses and the geology courses and the medical-type courses we got, all that was focused on stuff we’d have to know to operate in the office and at least understand and be reasonably cognizant of some of the importance of the various experiments that we would be doing on the various missions and stuff. So I found that real fascinating.

For example, he said, the astronomy course was a real standout for him in the training. “He’s passed away now, but the astronomy course was Professor Smith out of University ofTexas, and he was kind of your almost stereotypical crazy professor,” Brandenstein said.

I mean, he was just a cloud ofchalk dust back and forth across the blackboard as he went on. We had twelve hours of astronomy; he claimed that he gave us four years of undergraduate and two years of graduate astronomy in twelve hours. And it gave you a good appreciation of what it was all about. It didn’t, by any stretch of the imagination, make me an astronomer, but the intent of it was to give you an appreciation and give you an understanding. And then also because of the very special instructors they brought in, it gave you a point ofcontact, so if somewhere later in your career you had a mission that needed that expertise, you had somebody to go up to and get the level of detailed information you needed.

Brandenstein said that he was very grateful that the format of the classes was just to absorb as much as possible from the barrage of information; there were no written tests. “Everything was pretty much that way. It was just dump data on you faster than you could imagine. A common joke was that training as an astronaut candidate was kind of like drinking water out of a fire hose; it just kept coming and kept coming and kept coming. Probably the good point of it was you weren’t given written tests, so they could just heap as much on you, and you captured what you could. What rolled off your back, you knew where to go recover it.”

Everybody in the class had their strengths at some point in the training, and Brandenstein said the pilots enjoyed when the training was on their home turf. The pilots in the group, he said, liked to take the mission specialists up for what they referred to as “turn and burn”—loops, rolls, and other aerobatics. “We’d go out and do simulated combat and show them what it’s like to have a dogfight and all those sorts of things. So that was [as] fascinating to them as me sitting down with an astronomer or a doctor and finding out about the types of things they did.”

Brewster Shaw said he came into the corps with very few expectations of what the job entailed, beyond eventually flying on the Space Shuttle. “I soon learned that the percentage of the time you got to fly the Space Shuttle was pretty miniscule, relative to the percentage of the time that you were here working for the agency, and that there was a lot of other things you were going to do that would take up all your time, and that was made clear to us pretty soon.”