Crew Given Go for Another Week in Space

Astronauts Carr, Gibson, and Pogue now in their 63 rd day in space were given the go for another seven days. For the remainder of the mission, weekly evaluations of crew, consumables, and hardware will be made by nasa officials. The second weekly review was completed this afternoon. Following the review of inflight medical data and the recommendation of Dr. Charles A. Berry, nasa Director for Life Sciences, William C. Schneider, Skylab Program Director, gave approval for the mission to continue until at least January 24.

Concerned about what effect the extended duration would have on the health of the astronauts when they returned to Earth, NASA doctors were getting more ambitious with the postflight medical protocols for the crew. NASA medical management had been persuaded, over the strenuous objections of some astronauts, that direct measurement of cardiac output by means of a catheter inserted into an artery in the arm and extended into the heart would give valuable data about the possible effect of weightlessness on cardiac function. A dry run was scheduled with the deputy crew flight surgeon as the test subject. A Johnson Space Center press release reported:

A volunteer subject fainted and suffered a brief loss of heart beat but was immediately revived during a cardiac output evaluation test conducted under controlled conditions for the Skylab medical program. The subject, Lt. Col. Edouard Burchard, required no hospitalization and was back on duty a short time later. The incident occurred after a needle had been placed in Lt. Col. Burchard’s artery during the test. He responded immediately to the normal therapy that includes an injection of atropine and external heart massage.

The test, conducted at the Space Center Hospital near the Johnson Space Center, was a simulation ofone ofthe postflight medical analysis checks considered for the Skylab iii astronauts after their return to Houston. The purpose of the test is to get a precise measurement ofcardiac output by introducing a dye into the blood system. Such dye dilution tests are routinely used in cardiac research diagnosis and medical officials said Lt. Col. Burchard’s reaction was very unusual. As a result of the incident, however, Skylab program officials have decided that the test will not be performed on any of the returning [astronauts]. Lt. Col. Burchard is a West German Air Force medical officer detailed to nasa. He serves as deputy flight surgeon for the Skylab iii crew.

So that was another worry off the minds of the crew. “Upon our return, we presented Dr. Burchard with a bottle of scotch with a note thanking him for ‘his willingness to protect us with his life,’ said Carr.

Another area of concern was the dwindling supplies available on Skylab. From the outset the food supply had presented a challenge—namely, there wasn’t going to be enough of it to extend the mission as much as mission planners hoped. Further, the “gold-rush” attitude of scientists who wanted to get their experiments on the manifest after the success of Skylab II further limited the amount of space available for other cargo on the Command Module, which carried the Skylab ill crew to the station. With a lack of food on the station and a lack of space to carry more food, there was a need for an innovative solution.

And an innovative solution was found: food bars. When the crew launched, they carried with them a supply of nutritional bars developed jointly by NASA, the U. S. Air Force, and the Pillsbury Company. “The difficulty with staying up that long was that we had only had enough food for fifty-six days and too many experiments to take up in the Command Module, which was already overloaded,” Gibson said. “So we volunteered, actually agreed, that every third day we would eat nothing but food bars. That was probably one of the most supreme sacrifices anyone has ever made for the space program by a crewperson—food bars! Every third day we each consumed four of these little guys. Breakfast, which lasted about thirty seconds, consisted of four or five crunches, and that was it. There was no more. Meal’s over. I still have a tough time looking a food bar in the face. But the bars worked, and we stayed. They had all the minerals and calories that we needed. It’s not an ideal way to live, but they did work.”

However, the lack of one item really bothered Gibson. “You just can’t overestimate the value of a good butter cookie,” he said. “We had an economic system on Skylab whose basic monetary unit was the butter cookie. But when we got up there, most of our money had been consumed previously by both the hungry Marine [Jack Lousma] and the Skylab I commander, Pete Conrad. It caused runaway deflation in the Skylab ill economy.”

As if eighty days of food bars every third day were not enough, mission protocols required that the crew follow their Skylab diet regimen for twenty-one days before the mission. Even after returning to Earth at the end of the mission there was no reprieve; postflight required another eighteen days on the Skylab ill food-bar diet plan.

Other supplies also became of concern. “In mid-January 1973, when we were enjoying one of our ‘days off,’” Bill Pogue said, “I was looking down at the Earth, Ed was at the atm, and Jerry was doing an inventory of our remaining supplies. He floated down to his sleep compartment and left a message on the в Channel tape recorder for the ground control folks. Jerry was telling them that he had discovered a shortage of approximately ten urine sample containers, which we each used every morning to replace our individual containers that we filled the day before. A part of this task was to draw off and put 122 milliliters (about the size of a large ice cube) into the sample receptacle, place the urine sample into a freezer, and put the used urine storage bag into a trash bag for later dumping into the Skylab dumpster.

“The next day Capcom called with a solution. We were to change out the urine bags every thirty-six hours instead of every twenty-four hours; using this procedure would insure the remaining sample containers would last to the end of the mission. We followed this makeshift procedure, and everything worked out fine. Still we couldn’t understand how the shortage had occurred because the people who prepared the mission equipment were highly competent. The waste sampling was to support a mineral-balance study conducted by the National Institutes of Health, and the principal investigator, Don Whedon, was most meticulous and careful. Once we got back to Earth we forgot the whole thing.

“Two months after our return the Astronaut Office had a ‘Pin Party’ for those Skylab astronauts who had made their first flight into space. The party is essentially a shindig where the backup crews roast the prime crews for many of their goofs and screw-ups during training and flight. The prime crews swallow hard, thank the backup crews for all their hard work, respond with good-natured humility and perhaps a few light-hearted jests of their own, and then make special individual presentations to their backup crews.

“Jerry, Ed, and I just about fell out of our chairs when Al Bean presented the missing urine sample containers mounted, on a plaque with a personal dedication plate, to each backup crewman. We looked at each other and burst out laughing. The ‘Mystery of the Purloined Pee Bags’ had been solved. They had been taken mistakenly by Al when the second crew returned to Earth. Of course we all quizzed Al and his crew about why they had developed a personal attachment to our pee bags.”

Of course, the crew and spacecraft were not the only ones affected by the duration of the Skylab program. Neil Hutchinson recalled that Mission

Control was also feeling the effects of the passing months. “It wasn’t like a prize fight where you train, fight, and it’s over,” he said. “In Apollo and now the early Shuttle flights, you train and train and train, then the mission goes, you work your tail off for a number of days, and the mission’s over. Skylab was never over.

“Chuck Lewis, another Skylab flight director, got very ill. I flew the last flight with a kidney problem that ended up in a very serious surgery. It’s not serious anymore, but in those days it was. It really, really took a lot out of people because you never got loose from it.

“We did all kinds of crazy stuff. We had our families in the control center for affairs to try and change the pace of things. I held a big dinner. Maybe all the flight directors did. It was a big sit-down catered dinner in the control center while the spacecraft was still up but during one of those times between manned missions. We were just trying to keep people’s focus and attention. Still we had guys drop out of teams, and we had to change players. It wasn’t that the control center was wilting on [Skylab ill], it really was the sum of the three missions; we were all on duty for nine months.

“But by this latter part of the mission, both the crew and Mission Control were feeling really good because it all was going dramatically better. It became obvious we would get everything done and then some, and everyone could see the light at the end of the tunnel. As the last weeks of Skylab ill went by, we all felt better and better.”

Finally, the end of the mission neared. “I recall the last six weeks of the flight were very pleasant for me for two reasons,” Pogue said. “One, we’d achieved the skill level sufficient to do the job quickly and accurately, and second, I no longer suffered from the head congestion that had plagued me for about the first six weeks of the flight. Midway through the mission it didn’t seem to bother me much but became more like a low-grade headache that doesn’t really hurt very much even though it still slightly decreases your efficiency.

“We all had a much better feeling about the whole flight toward the end. In fact they asked us if we would stay up for another ten days. James Fletcher, the administrator, had suggested it. Mentally we were prepared to come back, but more important, we didn’t have any food left even though we probably could have scraped together enough for a few more days. But we came back on schedule after eighty-four days.”

“Medically,” said Gibson, “there were at least two reasons for our feeling so good: after our bone marrow greatly slowed its production of red blood

|

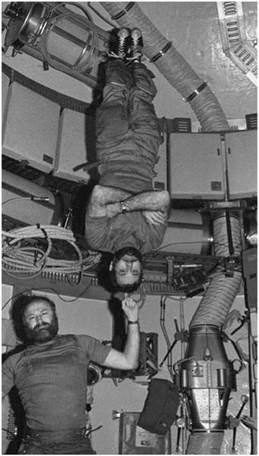

43- Carr and Pogue have fun with the possibilities presented by weightlessness. |

cells, because our hemoglobin concentration had gone up in the first few days of the mission when we lost about three pounds of plasma from our circulating blood volume, it took a while for the hemoglobin concentration to drop low enough to trigger red blood cell production again. That production brought our circulating red cell mass back to normal, if not higher, toward the end of our flight. Also the tone of our cardiovascular systems had improved as measured by our response to the lbnp, which saw us reach presyncope [nearly pass out] about midway through our mission, before we significantly improved.

“From a personal standpoint, I would have liked to stay longer. I had come to think of our space station as an average, three-bedroom home, just 270

miles high and whistling over the ground at five miles a second. It felt so solid, so secure, that it didn’t really feel like flying at all until we left it in our reentry vehicle. Then it felt just like leaving my home down here, sliding into a sports car, and accelerating back onto the road again. It was a comfortable home for sure, and I would’ve been content to live there for many years, if I had friends and family along. . . and maybe a good pizza delivery.”

There were things about the Earth that the crew missed, though. In his book of humorous space anecdotes, The Light Stuff Bob Ward, a newspaper editor at The Huntsville Times reported:

As the final Skylab flight approached the end of its nearly three months in orbit, Houston used the onboard teleprinter to send up changes in the plans for closing down the workshop and preparing for the trip back home.

Astronaut Carr noted that these teleprinted instructions stretched almost from one end of the space station to the other— about fifty feet. That evening, when the new team of flight controllers came on duty, Carr couldn’t resist remarking that he fully expected Houston next to transmit the Old Testament.

Later Carr notified Capcom Bruce McCandless that the Skylab 3 crew wanted a book sent up via teleprinter that evening.

“War and Peace? ” asked McCandless.

“No,”replied Carr, “Little Women.”

Then there was a brief pause and the astronaut added: “Bill (Pogue) says send him up a big one. ”

That the spacemen manning the last, and longest, Skylab mission may have had the opposite sex on their minds had been suggested a few days before the Little Women episode.

From orbit the astronauts had held a live press conference. nasa intended to include a set ofquestions from a sixth-grade class in a small town in New York, but time ran out. During the next orbit, flight controller Dick Truly went ahead and asked the children’s questions, anyway. He savedfor last the question ofone sixth-grader who wanted to know, Did the astronauts miss female companionship after so long a time?

Ed Gibson, taken aback by the frankness of the query, responded: “What grade did you say that was, Dick?”

Then the astronaut answered the precocious child’s question with a frankness of his own:

“Obviously, yes. ’”

Though the lumps given the Skylab ill crew by the media early in the mission would affect their reputation for years to come, coverage of their successes by the same media was not as forthcoming. As the mission neared its close, it was one of the first missions ever since the early Gemini missions that the flight itself was not extensively covered by the media. In fact they didn’t even cover the return after the crew had set a time-in-space world record.

“At the time it happened, I didn’t realize it,” Gibson said, “because I was not looking at it from the outside. People were making a big deal out of it being an exception, but once I thought about it after a couple of months, I realized that in a way it was good. We’re trying to make space to be more commonplace and space operations to be more accepted because they were being done repetitively and routinely. People can’t be sitting on the edge of their chairs all the time, especially during long space station operations. So it’s only natural that people’s attention would drop off. I thought, ‘Well, maybe we’ve reached a point in the space program where it’s become more mature and lack of day-to-day interest it’s only natural. So, let’s accept it and move on.’”

And so, for Skylab’s final crew, preparations for the trip home began. Before they left, this final crew of Skylab made sure to leave the welcome mat out for any future visitors. Although there were no plans for another Skylab mission, there were hopes that a crew of the Space Shuttle, which it was then believed would be in operation well before Skylab deorbited, might come up, check on America’s first space station, and even boost it to a higher orbit to extend its lifetime.

A time capsule was even prepared for a visiting Shuttle crew to return to Earth. In it were a variety of materials, which would allow scientists to study the effects of long-term exposure to the spacecraft’s environment. Although the time capsule was left inside Skylab, the venting of the atmosphere after the crew left meant that the materials were exposed to vacuum.

A few hiccups arose in getting ready to button up Skylab, close the hatch, and deorbit in the Command Module. “The frozen urine samples had to be put into an insulated container for their trip home,” Ed Gibson said. “Each of these frozen samples, about the size of a very large ice cube and often called ‘urinesicles’ by the crew, had expanded just slightly beyond the size allotted for them in the return containers. Thus I had a problem. Reentry was a few short hours away, and the whole sample return for a major experiment was in jeopardy.

“As beads of sweat seeped out, clung to me, and soaked my suit, out to the rescue came the old trusty Swiss Army knife with its coarse file! The sharp plastic edges on the entry lips of the containers were all then filed down to a bull nose so that the urinesicles could be forced into each container with only minimal damage. To say the least, I was elated that the knife was on board. Because of the concern for inhaling particles, we were not allowed to have files in the tool kit, but the one in the Swiss Army knife had slipped by detection.

“In the midst of these busy preparations to leave Skylab, the back of our minds began reflecting on its future. I thought that Skylab was a great office, lab, and home that had set the bar high for all space stations to come. And I also thought that in another three to six years, our current home would be replaced by either Skylab в, which is now sliced up and residing in the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington DC, or another space station, which would be much easier and cheaper to build since we had the Skylab experience. ‘We only needed a few large tanks, a couple of docking ports, a door for spacewalks, some first-class experiments, three or four cmgs to stabilize it all, and a few large solar panels hung on the outside for electricity. Nope, it’s not hard. All of it can be off the shelf. Let’s go do it.’ But that was not to be when it was decided to throw away the booster capabilities we dearly paid for in Apollo and hang our future on only one access to space, a shuttle.

“It all had seemed like it would be so simple, yet it’s come out so hard. The history of pioneering tells us that we shouldn’t expect progress to take place in a straight line. Thus, I have confidence that in the future we will have fully completed space stations in Earth orbit, each manned with six to eight highly competent personnel and that their scientific and technologic productivity will be judged far worth the effort by all but the most ardent critics.”

“Just as we were leaving Skylab, I almost had one last task to complete,” said Pogue. “We had lost a coolant loop between the second and the third missions, so one of the first things I had to do when we arrived was to replenish and recharge the glycol solution in the failed coolant loop. It was that loop that we used for our water-cooled long johns [liquid cooled garment]) that we wore under our space suits on eva. So I was really interested that

it worked. We got it fixed real quickly. But just as I closed the hatch as we were leaving, the other loop failed. They asked if I wanted to go back in to fix it. I asked, ‘Why?’

“After we got in the Command Module, we went through a long series of involved procedures. We were almost euphoric all during this period. Of course, we did a fly-around, and I took about seventy-five pictures of Sky – lab as we went around for the last time.”

“When we undocked and made one trip around Skylab to photograph its condition,” said Gibson, “it was obvious that the sun’s ultraviolet light had greatly discolored all surfaces. What was white preflight was now tan. Even the white sunshade sail erected by the second crew had turned a golden tan with one notable exception. As we maneuvered over the surface that faced toward the sun, both sunshades rippled and waved in the gas stream from our reaction control thrusters. The sail erected by the second crew still displayed the creases from when it had been tightly folded in its stowage container before Jack and Owen pulled it out and hoisted it up the twin pole supports. Jack had done a great job of unsticking and unfolding the sail, an unanticipated chore, except for one fold that now opened up under the wind gust of our thrusters. Like light from a cracked door, the material inside the fold beamed back a stark white in contrast to its surroundings, a feature readily apparent in pictures today.”

“Pretty soon after we separated,” recalled Bill Pogue, “we could see Skylab going away. After we did the first deorbit burn, which brought us down to about 125 miles, I remember thinking that, after looking at the Earth from 270 miles for several months, it was almost like hedgehopping at 125 miles where you perceive the ground going by a lot faster.

“Almost everything worked out quite well except that we did have a problem with the reaction control system in the Command Module. One of our two rings [sets of attitude control jets] system had already lost pressure and had to be deactivated. The official record says that they told us to put on oxygen masks at this point, but we never heard the transmission so we never had them on.

“The problem came after we had separated from the Service Module. I looked over at Jerry as he was moving the hand controller to get the right entry attitude, which we absolutely had to be at for reentry to avoid landing in the wrong location or being cremated before our time, and nothing was happening! I yelled, ‘Go direct.’ Direct is a mode that is entered by going to the hard stops on the hand controller, which bypasses all the black boxes and puts the juice directly to the solenoids controlling the propellants in the reaction control jets. It worked. We got close to the right entry attitude and threw it into autopilot, which steered us during reentry. No problem.

“When we got down on the deck, we were hoisted aboard the aircraft carrier, and everybody was in pretty good shape. We later found out that Jerry had inadvertently pulled all of the circuit breakers to the Command Module reaction control thrusters instead of those for the Service Module, which were to be unpowered to prevent arcing when the guillotine cut all those wires between the modules before they were separated. The Command Module breakers were right above those for the Service Module. Since Jerry was floating a little higher in zero gravity than in the simulations on Earth three months before and it was dark, it was an easy mistake to make. Human factors should dictate that you don’t put these sets of breakers adjacent to one another if you require that kind of a time-critical safety-of-flight procedure. He just pulled the wrong ones, which was a real easy error to make. But it turned out fine. That was our biggest excitement during reentry: Jerry moved that hand controller and nothing happened.”

“At first,” Ed Gibson said, “reentry was like living inside a purple neon tube whose brightness gradually increased when we began colliding with air molecules in the upper atmosphere at mach 25. About the time we got the.05-G light [reached a deceleration of one-twentieth of gravity], I felt myself start to tumble but in no specific direction. ‘Strange,’ I thought, but then my vestibular system hadn’t felt any linear acceleration for eighty-four days, and my brain was trying to figure out how to interpret these faint murmurs coming from my inner ears. As the Gs increased, this feeling of tumbling was replaced by the strong sensation of deceleration that eventually hit over four Gs. The violet glow had progressed to a white-hot flame, the Gs and turbulence continued to build, and it was now more like living inside a vibrating blast furnace. The flames from the heat shield streamed by my window and out behind us. Sitting in the center seat, I could watch the roll thrusters fire as the computer rolled the spacecraft to bring us down precisely on target, exactly three miles from the uss New Orleans, the aircraft carrier that waited to pick us up.

“Eventually, the light and turbulence subsided, a firm explosion above our heads told us the nose-cone ring had departed, and small drogue chutes streamed out to stabilize us. At ten thousand feet the drogues also departed, and the mains appeared. At first they were held partially closed or reefed, and then they billowed out to three good fully deployed chutes, which we were all happy to see. But I felt confused. Once on the mains we were obviously pulling only one G. But then why did it feel like we were still pulling three Gs?

“We splashed down onto a calm sea with no wind. However, we still ended up in what NASA called Stable 2. Translated that means that we were hanging upside-down in the straps, bobbing up and down on the water in a closed damp cabin with the heat of reentry soaking back in—for me the most uncomfortable part of the whole flight or recovery!

“Before we got the balloons inflated that would right us, my mind flashed back to our training when we practiced what we would do if we remained in Stable 2 and had to exit the spacecraft by ourselves. We did the training in a Command Module mockup, very much like the real one, in a water tank in Houston. A lightning and thunderstorm was in full bloom as we began the exercise.

“As we got out of our straps, prepared to dive down into the tunnel to open the hatch, continue further down and out the tunnel, and swim to the surface, we noticed that the mockup was actually sinking! A relief valve had not closed properly and water was pouring into our habitable volume. No longer was this a casual training exercise; this was for real. With very little breathing air left, the last of us made it out and to the surface, using a procedure we had never practiced before. The technicians outside had a crane that they could have used to pull the spacecraft out of the water—except that its use was not allowed when there was lightning in the area.

“I looked around our Command Module for signs of water. There were none. The bags inflated, we popped over to Stable i, and we gained access to the warm ocean air outside.

“We felt elated. We knew we had gone through an ordeal on this mission yet made many major accomplishments that contributed to the space effort. It was a mission of which we would always be proud perhaps even more so because we had worked through some early and very difficult situations before we turned it around and reached full stride.

“Nothing was left but medical tests, speeches, and a return to our families. Smiles were frozen onto our faces.

“Outside helicopters were hovering as frogmen jumped into the water and connected floatation devices and attachments to haul our Command Module aboard the deck of the uss New Orleans (lph-ii), an Iwo Jima—class amphibious assault ship (helicopter). It was clear these folks really knew what they were doing, since they had previously completed several Apollo recoveries.”

The uss New Orleans had been commissioned on 16 November 1968, exactly five years before the launch of the Skylab ill crew and wouldn’t be decommissioned until і October 1997. In addition to supporting real space missions, it also supported the filming of Apollo 13, the movie. It could accommodate twenty-five helicopters on its 592-foot-long deck and reach the scene of the recovery at a speed of twenty-five knots. It was the third of four ships in the U. S. Navy to proudly bear the name of uss New Orleans; the fourth ship, a San Antonio-class amphibious transport dock, was launched in 2004 and is still in service today.

Gibson continued, “Once back on the carrier deck, a part of me was depressed. No matter how hard I pushed off, I could no longer float. And no matter where I went, I was painfully aware that once again I had to haul along massive amounts of meat and bone. Later rolling over at night became a real engineering challenge. But the exercises that we did during our easy, lazy days of zero gravity, paid off. Unlike some other crews and after months in space, we could walk as soon as we landed and suffered no lasting effects.

“Yet even with the G-suit squeezing my legs and the switch on forehead thrown to one-G, I felt just a bit wobbly. We were all glad we had those G-suits because climbing out of the spacecraft, crumpling into a ball, and rolling off the platform into the crowd would not have been good public relations. After about two hours I could maneuver pretty well but with my feet spread wide apart. I suffered no nausea just as I hadn’t when entering zero gravity. Training, hard work, or fortitude had nothing to do with it—I was just lucky.

“After about two days, I could walk without any noticeable difference from my preflight gait, but it took about two weeks to hit my preflight performance in the balance tests.

“There was another disappointment to deal with when we came back. Without gravity in flight, each of our vertebrae had expanded a bit, and we each became about two inches taller. What a great deal! But our new height was short-lived as soon as gravity got us back into its clutches again.

“Upon return to Ellington Field in Houston, we had to stand on a platform for almost an hour trying to say something historic. The wobbly legs returned, and I again feared tumbling off the platform into the crowd. But the legs held and the wobble abated.

“Then I did a dumb thing. About four days after landing, I felt better than I thought I might, so I figured I ought to stop lollygagging around and get back to my standard exercise, a relaxed five-mile run. Wrong thing to do! Muscles and joints that had little stress on them for three months screamed their pain at me for the next two weeks.

“At least in addition to our pride and personal satisfaction, we were handsomely compensated by NASA. After all, we had traveled thirty-five million miles. Each and every day we received a government travel allowance, which because our meals, quarters, and transportation were government provided, came up to $2.38. Over our eighty-four-day flight, that came up to a whopping $ 199.92 for each one of us!”

There was great rejoicing when Skylab ill — and the whole Skylab program —ended in success. A lot of tired people got to know their families again. And the participants busied themselves with documenting their lessons learned for the future, hoping that the future would soon include a permanent space station.

Skylab had clearly demonstrated the value of human intelligence applied in a hands-on way onboard the nation’s first space station. It had also shown that humans retain all their abilities and needs even when they are several hundred miles up. Proper work scheduling, positive motivation, and meaningful communication are just as essential in flight as they on the ground, if not even more so.

Those directly involved began to reflect on what had been accomplished and contemplate our future in space. “But shoot,” said Pogue, “talk about something that was successful, Skylab was highly successful! It was our first space station and focused attention on long-term reliability of systems and proper integration and support of the crews. Apollo flights lasted eight days or ten days. That’s one thing. But when you stay up there for months, your systems and crews are going to see a much greater exposure to all the problems that are waiting for you in zero gravity and the space environment. Now we see how difficult it will be to design reliable systems and support crews for something as long as a Mars mission, which is nominally about two to three years.”

Ed Gibson said, “It was a great sense of accomplishment; we had met all our mission objectives, averaged as many accomplishments per unit time as previous crews, despite our slow start, and had set a world record for time in space. But in only a few short years the Russians eclipsed our mark.

“However, our mission did set an American record that lasted for twenty-one years. Actually we expected and wanted to have our American record broken within four to six years—on an American station! But that was not to be. Norm Thagard, a very capable guy, broke our endurance record, but he did it on the Russian Mir space station.

“We all recognize Skylab was the beneficiary of the program that came before it: Apollo. Skylab itself was constructed in large part with hardware that became available when the last three missions to the moon were canceled. Unlike today it was launched all in one shot using the Saturn v, which was the greatest rocket system the United States has ever developed. It could put 250,000 pounds into low Earth orbit, about seven times what the Shuttle can do today. It launched many flights in the early years and got the whole space program off to a fast start including Skylab.

“My own view of this fast start began back in 1957, when I, my parents, and Julie, my girlfriend then and wife now, stood out in the backyard of our home in Kenmore, which is just north of Buffalo. We watched mankind’s first satellite go over, the Soviet Sputnik. Back then, I’d never heard the word astronaut. But just fifteen years later, my parents stood out in the same backyard and watched me go over.

“But the rapid pace and success of the early years was not because of hardware alone; people and leadership made it happen. We in the astronaut office closely experienced one of the very best: Deke Slayton. He was one of the Original Seven astronauts but was medically grounded before he could fly. Rather than quit, he was driven to contribute wherever he could, and he was appointed the head of Flight Crew Operations, which included the challenge of keeping over forty headstrong astronauts under control, a daunting task. But he was tough and very mission focused. If you were also there, like him, to advance the mission, he gave you his full support. If you

were to advance yourself, he’d rip out the flamethrower and turn you to a crisp in nothing flat. He was the right guy for the job.

“In Deke’s demands for an overwhelming focus on the mission, which he applied unselfishly to himself as well, he was tough but fair, harsh but kind, someone I respected, trusted, liked, and feared all at the same time. I’ve seen many leaders in my career, some very sophisticated, but I regard Deke as one of the best I’ve ever encountered. He and many others like him made Apollo and Skylab happen. To the cheers of everyone around him, Deke finally did get to fly on Apollo-Soyuz, the joint U. S.—Russian mission after Skylab.

“Future space stations will have a hard time matching Skylab’s high scientific accomplishments for its relatively low cost. Based on Skylab, we should expect that future stations will discover new materials of engineering and biological importance, as well as new knowledge of how our bodies function without gravity, important for better understanding how they function right down here on Earth, as well as on future long-term missions far from Earth. But with the more complex systems that must last for many years, not just months, we would expect that proper manning of a station should reach at least six crewpersons, preferably seven or eight, to keep the station in full operation, properly perform really top-notch science and technology experiments, and realize the real potential of a space station. There is no good reason that we cannot perform Nobel Prize-quality science up there, just as we do down here!

“In the long run, despite tragedies and budget droughts the prospects for America in space remain bright. Most important, we have within our people, still, a spirit and will that wants nothing more than ever-deeper explorations of space, and its profitable use. We have physical facilities in America second to none. And charging in the front door, we have our youth, equally motivated and far better trained than those young engineers who took us to the moon and into Skylab. Lastly, we have our graybeards, engineers and managers with the knowledge and wisdom from decades of experience.

“Certainly, in time, we will complete and properly staff the International Space Station, return to the moon, land on Mars, and eventually explore the rest of our solar system. But beyond that? In the back of my mind I speculated when I was on Earth’s dark side during evas. The stars were clear, steady, and not a twinkle to be seen in any of them. A dense hemisphere of

stars swelled into existence as my eyes got dark-adapted. There’s got to be life out there!

“As we find more and better ways to visualize planets around other stars, we just might visualize a blue planet, one with an oxygen atmosphere. Then the pull would be irresistible. We’d have a crash program for near-light-speed flight, then a mission that’d fire our imagination far more than any fantasy from Star Trek. But we all understand that the distances are immense. On our Skylab flight, we traveled thirty-five million miles, which is the distance that light goes in just three minutes. Yet it takes light over four years just to reach our closest neighboring star. Clearly when it comes to deep space travel, we’ve just barely put a few layers of skin on our big toe out the front door.

“But it’s also clear that we’re on the front end of something much larger than any of us can imagine, travels and adventures far greater than anything we can now picture. And it’s also clear that we’ll never stop exploring, never stop reaching outward—it’s hard-wired into our psyche. I believe that if you scratch deep enough into the tough hide of even the most cynical, hard – boiled, space engineer, like a few of those you’ve encountered in this book, lurking at their core you’ll find a Trekkie; that’s someone who realizes that space probes and all their data are interesting, often exciting, but ultimately, it’s we who have to go there, in person, to see and feel new turf up close before it truly becomes a real part of our own world.

“One day, certainly in the long-term, driven by the human spirit, we will travel in vehicles that are derivatives of Skylab and subsequent space stations out to the rest of our solar system and, eventually, beyond.”