High Performance

What is it like living in space, not just visiting for a little while but actually setting up a home and living and working there for two months? Beyond the novel and unique circumstances encountered immediately, what is day-today life like as a “resident in orbit”? In other words what is it like to “homestead space”? And, when you return to Earth, how do you hang on to an accurate memory of the unique experiences you’ve lived through?

For two members of the Skylab 11 crew, the best way to remember the details of their homesteading adventure was to maintain an in-flight diary. It would have to be done in the minimal time available after all the science and other work was accomplished. Yet both commander Alan Bean and science pilot Owen Garriott maintained a journal during their time on Sky – lab, preserving not only a chronology of mission events but also a personal record of their thoughts and impressions during their stay in space.

“We launched and arrived at Skylab on July 28, 1973, called Mission Day i,” Garriott explained. “As you may imagine, we were pretty busy at first and even though I hoped to make entries in my in-flight diary every day, some days were just too full. Still, as I reread the entries today, now over three decades later, the mission flow and a sense of continuity remain. It was actually Mission Day 4, or July 31, before I had a chance to make my first entry.”

Alan Bean wrote in his journal after going to bed at night, as a way to wind down his day. Neither of his fellow crewmembers was even aware of the existence of this diary at the time—nor, for that matter, until more than thirty-two years later when he contributed it for this book.

(The excerpts from the Bean diary in this chapter have been modified with direction from Bean, for the sake of clarity. The entire diary is reproduced in unabridged form as an appendix.)

Alan’s first writing was done on Day 10 (6 August 1973), although he starts by referring back to events prior to launch:

Bean, md-i:

Launch Day. I am writing this in the morning of day io. Could not sleep, eva today, so thought I might catch up. Slept well early tonight [the night before launch], took Seconal and hit the bed about 7pm, so did Jack and Owen. Awakened on time by Al Shepard. He andDeke [Slayton] kept track of us the last few weeks more than usual. This has mixed blessings…. First there were the microbiological samples. Then physical. Then eat. . . . . Al Shepard rides with us in van as far as the Launch Control Center. I watched him because he held the rdz [rendezvous] book—when he got up to get off, he forgot [to leave the book] and I had to ask. On the way he told us he was our last minute back up—he then mentioned John Glenn having his suit at the suit room prior to Al’s first flight [ready to take Al’s place].

Despite the thruster problems during their approach and rendezvous phase, the SL-3 crew was able to dock with Skylab with no further problems. The hatch was opened, and Skylab became the first spacecraft to be lived in by two different crews.

Lousma described his first moments in his new space home: “I remember being in the Multiple Docking Adapter, in which everything was oriented around the circumference. And I never did figure that out for two months.” Most of the architecture in the workshop, including the lower deck used for experiment and living areas, had a normal Earth-like configuration, where there was an “up” and “down” as on the ground. But when an astronaut floated through the Airlock Module or the Multiple Docking Adapter, he was never sure what orientation to expect. It always required examination of the experiments mounted around the circumference to get in the proper position to operate the hardware.

Very shortly after the crew entered the Skylab, though, a new problem arose. As they began settling into the station, the symptoms of space sickness began to be felt.

Garriott, MD-4 (9:30 p. m. on 31 July):

Writing in “mid-air"— difficult!—First day, thru rendezvous, no noticeable or unexpected symptoms, altho didn’t want much to eat. After rendezvous I began working in the md/ows, did notice symptoms of “stomach awareness". Jack did become sick, but problem with adaptation not fully realized.

By md-2, wanted almost nothing to eat & intermittently became very queasy.

Believe I had one Scop-Dex that evening & an hour later began considerable improvement in feeling & outlook. Still not hungry. Jack sick several times early, then got on Scop-Dex with some improvement. Al usually pretty active but indicates problems with too much head movement. Message arrives saying take Scop-Dex tomorrow & if start, take another one every 4 hours. On this day (md – 2), I do ~jo min of head movements after pill. Jack & Al don’t [do head movements], altho they took drug.

NASA was already well aware of the possibility of “space sickness,” but the fact that the first Skylab crew did not encounter much if any space sickness may have led people to think that it might not be encountered on later flights as well. “My diary concentrates on the ‘stomach awareness’ or ‘space sickness’ for several reasons,” Garriott explained. “It was a major objective of the flight experimentation to find out the degree of discomfort and hopefully how to minimize or avoid its occurrence entirely. We were equipped with the best medication available at the time, pills of scopolamine/Dexe – drine, which we had all tried before flight in situations challenging to one’s vestibular system. For example, in aircraft ‘zero-G flights,’ which make many or even most passengers (including experienced pilots) nauseous, a ‘Scop – Dex’ capsule will usually eliminate any tendency to become sick to one’s stomach. We had a rotating chair on board Skylab, tested preflight many times. Anyone with a normal vestibular system is essentially guaranteed to vomit when exaggerated head movement coupled with rapid chair rotation is continued for ten or fifteen minutes!”

Lousma had the most immediate problem with nausea, followed by Garriott, and then Bean. The crew was supposed to begin promptly the process of reactivating Skylab after its period of dormancy following the first crew’s departure, but the symptoms they were experiencing made getting much done quickly a daunting prospect.

“I started not feeling good when I took my suit off in the Command Module,” Lousma said. “We didn’t take any medications before we left because we didn’t want to slow our reactions, and I didn’t expect to feel bad. But when I took off my suit, I started not to feel so good. When I got into the space station, the Skylab, I didn’t feel any worse until I really started moving around. But when I started to work, and getting things unstowed and set up, then I started feeling like my ‘gyros’ were going around and around. I thought, ‘If it’s going to be like this for two months, it’s going to be a long two months!’ ”

The problem, Lousma added, got worse the more he moved around but would abate somewhat when he rested. “I think probably the best cure was to recover to the point where you don’t feel so bad and then strike out again until you did. Every time you could last a bit longer before you had a problem with it. For about two days, I felt just a little bit of vertigo. But I continually improved. I think the thing that was most debilitating was, because I didn’t feel good, I stopped eating for a while. I just didn’t feel like eating. So I think I got behind the power curve in terms of energy—just didn’t have enough nourishment—and it took a little time to build that back up.”

The mission commander’s experience was much the same. “We all got kind of upset stomachs to different degrees,” Bean recalled. “If I would be still, then it would gradually go away. But then I wouldn’t be doing any work. So my feeling was, if I would stay still, then I felt okay, but you couldn’t activate the workshop that way. I would work as much as I could, and when I’d zoom around and unpack, pretty soon I’d start feeling an upset stomach. So I’d just have to slow down. It just took a lot longer. I never did vomit, but if I’d kept going, I would have.”

Bean also recalled that not only did the symptoms slow work down but they made the thought of eating unappealing. Since the crew was going to have to eat, doctors on the ground recommended that they try eating four or five smaller meals a day to see if it would be easier to get through their daily menu with it divided up into smaller portions. Bean was disappointed at the prospect of a work pace already slowed by nausea being further reduced by having to stop frequently for meals. “I kept wondering if the nausea was going to be like this for the whole fifty-six days,” he said. “I kept thinking, we can do it but it’s sure going to slow down what we want to do. We had all these plans of activating the workshop real quick and getting right to productive experimental work. We wanted to be the best we could be as a team, and so this was distressing, and yet, that’s the best we could do.”

Lousma recalled, “We all kind of helped the other guy out, and I was probably the guy that needed more help than anybody. But we worked together to do the things we needed to do to get situated. And sure enough, after about five days we got well, and we could just zip around and do our jobs and everything.”

The problem kept the crew from getting the start they would have liked on their work, but it did not affect their relationship with Mission Control.

“We were also honest with the ground,” Bean noted, “even though it was a little embarrassing; we thought of ourselves as a ‘right stuff’ crew, and ‘right stuff’ astronauts don’t get sick! Later, when our flight was over, we proved that ‘right stuff’ crews can get sick, provided they find a way to overcome it and perform well before they come back to Earth.”

In addition to their vestibular concerns, the crewmen noticed other physiological changes, including some involving bodily functions of considerable interest to elementary school children, judging by their inevitable questions to astronaut speakers about these matters. “Of course, in reality, everyone has these questions in mind, but it is only the uninhibited children who bring up the issue immediately,” Garriott noted.

Bean, MD-3:

We are farting a lot but not belching much —Joe Kerwin said we would have to learn to handle lots of gas.

Got to stop responding to ground so fast and just dropping what I am doing— causes us to run behind on the time line. Do not know just what to do about this. . . .

Still losing a lot of things, too big a hurry. Wish the flight planners would let up. The time taken to trouble shoot the condensate system shoots this whole timeline. Got to stay on schedule.

The intestinal gas issue was not a direct effect of spaceflight itself as it was also encountered by the smeat crew on Earth. The cause is more likely that the human body generates a certain mass of gas depending on one’s diet, and in a low pressure environment (5 psi in Skylab and smeat versus 14.7 psi on Earth at sea level), the gas expands to about triple its normal volume.

Garriott, MD-3:

On MD-y everyone improving but still slow & inefficient. Incidentally, we have all been working from 0800 till 2200—2400, with almost no breaks. Only a few minutes devoted to looking out window (Fantastic —Gulf of Mex, Hou <—> Yucatan; Pacific Coast, Hawaiian Isl, Mediterranean], etc!) Believe we each had 2 Scop-Dex. Seemed comfortable, except at meals. Meals are bad for everyone. No one sick, Jack worked all day, with difficulty. eva day keeps slipping!

While the crew was able to go about most of its assigned tasks, albeit more slowly than planned during those first couple of days, changes had to be made regarding another major task — an eva that had been scheduled for Mission Day 4. “The ground controllers were most sympathetic to our problems, and we all agreed that we should slip our first eva day until we were feeling better,” Garriott said. “It could be a disaster if either of the two eva crewmen, Jack or I at first, were to vomit while outside in our pressure suits.”

Though their trip outside was delayed, the crew was gradually becoming more efficient at the work to be done inside the station and to get caught up had already started working extended hours (something that was to be a theme throughout their stay on Skylab). Still they took rare opportunities to appreciate the unique vista their accommodations accorded.

“An early surprise for me came on MD-3 when I was not yet used to the great distance to the horizon in all directions,” Garriott recalled. “We had just passed over Houston, where our homes and families were located, and I was watching out our wardroom window to see all the familiar terrain pass beneath us—the large white buildings at the Manned Spacecraft Center (appearing as small dots), the freeway to Galveston, Clear Lake where the whole family enjoyed (sometimes!) small boat sailing races. It all was past my view in only a few minutes, when I looked toward the top of the wardroom window and there was an island in the middle of the Gulf of Mexico! But there are no large islands in the Gulf! I immediately realized that my field of view extended all the way from Houston to Yucatan, the ‘island’ I was now viewing.”

Garriott, MD-4:

Supposed to be a day off, altho MD-3 was too. No one took Scop-Dex. Al & I very near normal, Jack much improved. We all went thru m-ijiprotocol [experiment on metabolic activity] on bike, w/o instrumentation & no bike mods. I did 30 head movements of131 type [vestibular function experiment], w/ no effects. Believe my vestibular system nearly adapted after ~j2 hrs, certainly almost so. Appetite improved, but still not good. Had to force down a filet tonight. Whew! Paul B. [flight physician Dr. Paul Buchanan] hadgood news for later meals—eat what/when we want.

As the ground-based pi s (principal investigators) wanted all the vomit and fecal material to be returned for postflight analysis, it was all placed in sterile bags and inserted into a specially designed pressure-tight enclosure that could be both warmed and vented to a vacuum. In this way all water

was evaporated in a few hours, leaving a dry and easily managed residue for return to the ground.

Bean, MD-4:

Jack was taking a cooked fecal bag out of the dryer— laughing— here is a real nice ripe one. I said, bet you are a goodpizza cook. No, said Jack, pancakes. We had too many fecals and vomitus bags to cook—

MD-5:

We’re in extremely high spirits today, first day we allfeel good. Owen said that today we ought to ask for a reduction in our insurance rates because we were no longer running the risk of drowning or auto accident.

The crew had run the lbnp (lower body negative pressure) experiment on Day 5, which subjected their bodies to stress similar to what would be expected when standing erect back on Earth, and all did pretty well. Now that everyone was feeling better, it was time to reschedule the spacewalk. Day 6 seemed about right, and plans were set in motion. Those plans, however, fell through when the second thruster leak was discovered. As the crew and the ground worked to determine the cause and implications of the second thruster failure, the eva was once again delayed, this time until Day 10. In the meantime, life and work on Skylab continued.

Garriott, md-8:

Yesterday we all felt perfectly fine. Fully adapted & enjoying 0g Appetites improving but not up to normal, and “weights" (or, more accurately, body mass) stable for several days.

Their vestibular problems were far enough in the past that the crewmembers were enjoying the experience of weightlessness. They were also working to get caught up after having fallen behind schedule during their days of malaise, undertaking all of the tasks they were able to do. The crew could accomplish all the medical experiments and Earth resources protocols, but the solar physics agenda was greatly constrained because most of the cameras required film that could only be replaced by eva.

“On md-9, we accomplished two of the Earth resources operations,” Garriott said, “which was kind of a big deal because it required a major change of Skylab’s attitude in space. The whole station was reoriented with use of the large control moment gyros and pointed toward the Earth instead of

|

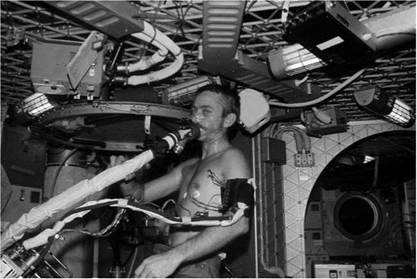

33. Garriott exercises with the cycle ergometer. |

the sun. We worked these experiments early, since we still had no film in the solar cameras.”

Bean, MD-9:

Left sal [Scientific Airlock] vent open last night after water dump. Thought I was so good at it, did not use check list—fooled because this was first night without experiment in sal. [Skylab featured two Scientific Airlocks, which allowed small experiments to be exposed to vacuum outside the spacecraft. One, on the “sun-side” of the station, was used for the sun-shield parasol, and couldn’t be used for experiments the rest of the mission. The other, on the opposite side of Skylab, could still be used.]

Owen let Arabella out of the vial. She had been in there since days prior to launch. She had not come out so Owen got the vial off the cage, opened the door, shook her out where she immediately bounced back andforth, front to back, four or five times, then locked onto screen panels at the box edge provided for visu – alization-there she sits clutching the screen. Owen and I talked of giving spider food because she has not moved one halfday. Owen said “no” because when she gets hungry is when she spins her web. She can live two-three weeks without if she has to.

First back-to-back erep. Jack [looked for] Lake Michigan. But got Baltimore instead. Or Washington, his prime site.

Saw what we thought was a salt flat but turned out to be a glacier in Chile. We could see Cape Horn—Cape Horn and Good Hope all in one day, fantastic.

Owen wanted to know if we had tried to urinate upside-down in the head [the waste management compartment]. He said it is psychologically tough. Jack said he tried it and he peed right in his eye.

Diving thru workshop different than in water— here the speed that you move (translate) is controlled entirely by your push off so for some spins or flips, you can have a V2, 1У2, 2 V2, 3 V2, etc. body rotations. Difficult to push off straight and to get spins you want. You must watch your progress as you spin—it’s tough to learn but to keep from hitting objects, it’s a must.

It was a great day —first back to back erep and it came off perfect. Jack and Owen good spirits for eva tomorrow—we worked all afternoon and evening on prep, much more fun than on Earth in ig.

Owen worked 22 hours today because he counted his sleep cap time. Every day is filled with memorable experiences—sights, sounds, emotions, hope, fear, courage, friendship. I just wish we could go home to our wives at night.

My urine volume lower than Owen and Jack. Been drinking a lot but must do better. Been concentrating on eating too much. Owen said meals were the high point of a day on Earth and here too. Only difference is there it’s the start, up here it’s when you finish.

I cut a hole in the bottom of my sleeping bag near the feet — too hot, had to tie a knot to keep from freezing in the early morning.

Heard about leak in am [Airlock Module] primary and secondary cooling loop. Pri should last ij days and secondary 60 days. Wondering what ingenious fix they will come up with [on the ground].

No csm master alarm today. Almost a “no mistake"day.

Arabella and Anita became well-known names in 1973. The public was enthralled by the two “cross spiders” prepared for spaceflight by a high- school student in Massachusetts, Judith Miles. “Fortunately, ‘cross’ refers to a large mark on their backs, and not to their disposition,” Garriott remarked. Miles proposed an experiment to study their method of web formation in weightlessness, which is a clue to their mental activity as they adapted to the microgravity environment. Arabella was released into her fully enclosed box from the small metal container about the size of one’s thumb. Her initial webs were very scruffy-looking, but every day they improved after she consumed the last one and spun a new one. The webs finally ended up looking

every bit as good as they would in an Earthly garden. Despite Bean’s concerns, the spiders remained healthy, and after about three weeks Arabella was returned to her container and Anita released. She proceeded to exhibit the same behavior as Arabella, even after being cooped up in that small container for about a month.

“I remember when we got Arabella out,” Lousma said. “This was Owen’s job; he’s the scientist. We hooked up this box with this open door. He said, ‘Hey, Jack, how about helping me get this spider.’ So we got the spider out. And it didn’t know where it was, the poor spider. Finally, she figures out she can stick herself on something and somehow fasten herself.”

Arabella and Anita captured the public’s fancy, and Lousma, who gave the public a look at Skylab with his televised tours, admits feeling a bit of jealousy at the time over the spiders’ status as spaceflight superstars. “It really disappointed me a little bit that on the ground the general public got more insight into what was happening with Arabella than what we were doing.”

The two spiders were the subject of a “gotcha” the second crew considered leaving for their Skylab successors. They had a large (fake) spider and web to place over the docking adapter hatch when they left. Unfortunately they mistakenly thought it had been left on Earth and didn’t set it up.

Around this time Harriott began to get calls from the solar science team on the ground about one somewhat obscure item he had not yet completed. The first mission had found that the xuv monitor, which enabled them to see the sun in extreme ultraviolet (xuv) light, had extremely low sensitivity, and the TV display was so faint as to be useless. So the ground developed a small conical light shield that the operator could place over the TV display and peek through the small hole at the apex of the cone. “Even this was still too dim,” Harriott said, “so we were provided with a recent technological marvel called a Polaroid camera! When the camera shutter is opened, it remains open until enough light has been passed through to properly expose the film. So this was ideal for us—we mounted the camera at the cone apex looking down on the TV image. When enough light had been accumulated, the shutter closed automatically and the camera developed the print. As you probably remember, it then went ‘bzzz’ and delivered the print out the bottom of the camera.

“Every day they asked if the xuv monitor camera had yet been installed and operated. ‘No, not yet, but I’ll get to it soon,’ I replied. After three or four days, it became clear they were really interested in how it was going to work, so I took time to set up the conical cover and the camera. When complete,

|

34- While their early efforts indicated trouble adapting, the spiders were quickly able to spin webs that appeared as they would have on Earth. |

including the preinstalled first film pack, I thought I should check out the camera operation before trying it on the sun. As Jack floated into view, I snapped a quick photo, followed by the ‘bzzz’ and out came the developed print—of a recent Playboy centerfold! All ten sheets of that first package were similarly pre-exposed and we all had a great laugh. But we never said anything to the ground about it until they made their next inquiry about the camera. I then reported that ‘Yes, the camera operation was normal and providing quite interesting photos.’ That was all that was ever mentioned inflight, and only on the ground two months later did we congratulate Paul Patterson on the Naval Research Laboratory solar physics team for his creative ‘gotcha’ and amusing surprise.”

Bean, md-io:

eva day. I had a tough time sleeping, ok for first 6 hours or so then off and on —finally writing at normal wake up time, iiooZ (0600 Houston) because they let us sleep late. Bed is great. I am going to patent it when I get home. The bungee straps and netting for the head and the pillows were my idea. Might come in use someday because no other simple way to make og feel like Earth.

Jack sleeps next to me then Owen at end— the reason, his sleep cap equipment fits better.

Funny how good we feel now, I think [at the beginning ofthe mission] we all

would have said “to hell with this, let’s go home”. No one ever said it in words but that was the way we all looked at each other around day 2 and 3.

Sleeping is different here because the “bed clothes” do not tend to restrain or touch your body. This causes large air space about your body, that your body heat doesn’t hold. It’s difficult to snuggle down. Have to put undershirts (long) and t-shirt on during the night. I cut feet out of the long handles then use them for pajamas. Also I mod’ed [modified] my bed by cutting a hole in the netting near the feet, too cold at night so close it up with a knot.

Little worried, Funny —Owen’s PCU [Pressure Control Unit] is #013 and his umbilical is #13. I’m not superstitious, but. . .

Started taking food pill supplements today. Kit is junkie’s paradise.

Jack discovered new way to shake urine collection bags to minimize bubbles. I called ground and said, “we even have our professionals — Owen atm checkout, me condensate dump, Jack urine shaking ”

After being delayed for nearly a week, the time for the crew’s first spacewalk finally arrived on Day 10. Jack and Owen were assigned to go outside on this first one, leaving Al inside to tend the store and assure everything went well. When the missions were originally planned, before the launch of Skylab, film replacement was to be about the only thing to be done on this spacewalk. But now the work needed to be almost doubled. The parasol that had been extended through the Scientific Airlock during the first mission to shield the workshop from the direct sunlight had been in place for over three months. Its ability to shade the workshop was beginning to deteriorate. Still aboard the station, however, was the second thermal mitigation system that had been launched with the first crew back in May, the Marshall Sail twin-pole sunshade. Installing it should again cool temperatures that were very gradually beginning to rise again as the parasol’s efficacy diminished in the sunlight.

“We had the twin-pole sunshade to deploy over the top of the parasol in addition to the film replacement,” Garriott said. “So after the film installation was first completed, I had to connect eleven five-foot sections of aluminum poles, twice, forming two long poles. These were then extended to Jack some forty or fifty feet away, where the poles were mounted in a v, and a large ‘sail’ pulled across them with nylon lines. This may have been the only ‘sail’ this Marine has ever rigged, and without a bit of wind to fill it out!”

As had been the case with the solar-array wing deployment conducted by the first crew, Skylab had not been intended to support spacewalks like this. No provisions had been made for spacewalkers to get around, save for the limited path installed to access the atm film canisters. For the work he was to be doing, Lousma had no translation aids provided to help him reach the area from which he would be installing the sunshade. Garriott remained near the Airlock Module hatch to remove the segments of the poles from their packaging, mate and lock each piece together and then extend the long poles to Lousma who had positioned himself far out on the truss structure. (Even without translation aids on Skylab’s exterior to help him reach his destination, Lousma was in no danger of floating off into space, since he was connected to Skylab by an umbilical running back to the Airlock Module.) Once he was in place where he would be doing most of the work, Lousma had a set of foot restraints designed to attach to the structure at that location and secure him in place. “You just kind of clamped them on, and you could stand there and enjoy the views,” he recalled.

After getting into position, Lousma next had to mount an adapter to the truss that featured two slots into which the long fifty-five-foot poles would be inserted. Garriott began putting the pole segments together with a standard bayonet-type connector. He fitted each segment into the next, depressed a spring, rotated the segment about twenty degrees, and latched it into place. Then a rubber ring was rolled over the fitting, securing the connection. On a later spacewalk, the crew found that this rubber locking ring had rolled back away from its connection, but the bayonet connection had been adequate to hold the segments together. When the two long poles were assembled, Garriott passed them on to Lousma, who fixed them into their slots, so that they stretched all the way to the far end of the workshop. Lousma then had to deploy the sunshade onto the poles, stretching it across the poles with long ropes or “lines,” eventually covering almost the whole workshop exposure and the old “parasol” deployed by the first crew.

While assembling the poles, Garriott encountered an unexpected problem. During the preflight testing of the sunshade equipment at the neutral buoyancy tank at Marshall, a difficult decision had been faced: whether to take the flight hardware underwater and then into space and risk corrosion and malfunction or only test it on the dry floor out of the water without the added realism that practice in neutral buoyancy would provide.

“We finally decided that for the twenty-two pole segments, a floor test without pressure-suited operation, would be adequate,” Garriott said. “This was about the only compromise made in testing under the most realistic conditions possible. Naturally, this returned to bite me in space. When I had to remove each individual rod segment from their aluminum transporting frame on which they were all mounted—manually, in a pressure suit—my ‘fat’ fingers in their thick gloves could not get under the rods to lift them against the elastic straps that held them tightly against the transporting frame! I ended up having to squat down in the pressure suit, holding the frame beneath my foot, use one hand to lift each rod upward against the surprisingly tough elastic, and then use my other hand across my body to wrench each rod from under the elastic strap. It may sound simple, but it turned out to be the most difficult physical task of the whole eva, which we might have been able to modify had we tried it all in a pressure suit on the ground. And I had to repeat all this about twenty-two times! (Send this to the ‘lessons learned’ department!)”

Lousma recalled that the neutral-buoyancy training had served him quite well. “We learned how long it took us to do each task, and I think it took us twice as long in space. That wasn’t because we weren’t prepared. It was simply because we had the time and wanted to do it right. And we worked slowly and double-checked and rechecked everything as we were doing it.”

There were all kinds of concerns that the twin poles were going to be too “whippy” because of their relatively thin diameter compared with their fifty-five-foot length, which Lousma said made them not unlike a giant fishing pole. “I wasn’t worried about that too much,” but he could tell a difference as they got longer. Lousma also encountered one unanticipated problem during the spacewalk. “The twin-pole sunshade worked very well, except for one little episode,” he remembers. “When you look at the Skylab photos the sunshade is kind of brown, but has a white streak in there.”

When the sunshade was packed for launch, it was “folded like an accordion” into a bag. However, because of the rush to get ready to fly during the ten-day period prior to the launch of the first crew, the adhesive used to attach the pieces together had not had time to cure fully before the sunshade was folded up and packed. As a result, when Lousma unpacked the sunshade in orbit and began to deploy it, the adhesive prevented it from unfolding as well as it was intended to do.

“So I had to bring that whole thing back toward myself,” he said. “It was all out of the bag and billowing up all over, and by hand I had to unfasten all of those folds. Then I had to attach the two corners that were nearest me with a long lanyard, and drift out to two places on either side of the mda to attach the lanyards. When the large sail was deployed, the twin poles were flopped down on top of the parasol and against the Skylab workshop, and the lanyards tightened. It nearly covered the workshop and worked quite well. So that was done, and I thought, end of story.

“But it turns out that I had missed one of those folds, and so it was out there like that for a long time, and getting browner and browner. Then the sun did the rest of the job and unstuck that one little piece. And so you see that white streak in there, that was the one that had remained folded for the longest time.”

Lousma estimated that the sunshade deployment took up about three hours of a six-and-a-half-hour spacewalk. In addition to the routine atm tasks and the sunshade, he and Garriott also explored the exterior of Skylab to try to gain clues as to the location of a coolant leak. The source of the mysterious leak would plague the second crew throughout their tenure on the facility. “During our inside time we also had to do quite a bit of exploration, taking some panels off,” he said. Removing the wall panels allowed access to the station’s “plumbing” but proved to be a difficult task since it was another maintenance activity that had not been anticipated preflight. Assuming that there would be no reason to detach the panels, engineers had designed them to remain firmly in place with no simple mechanism for removal. Despite their efforts, the second crew was unsuccessful in finding the source of the coolant leak. Ultimately a method was devised for the third crew to recharge the coolant supply, yet another unanticipated procedure.

The atm film exchange provided Garriott with the opportunity to do something he had been looking forward to. “One of the first things I did for fun was something I had planned before flight,” he said. “Is there anyone who has not looked over the edge of a high cliff or a tall building and felt an extra surge of emotion and adrenalin at the view? So here I stood at the front end of the atm solar telescopes to replace film, but could also look straight down a 435-kilometer (270-mile) ‘elevator shaft’ to the ground! It is a different perspective when in a pressure suit with nothing between you and a hard vacuum other than a thin, Plexiglas faceplate, as compared to looking out the window of a jet aircraft or even the wardroom window of Skylab.”

Bean made a special addendum to his diary about the spacewalk:

Jack said, being out on the sun end, was a little like Peter Pan—or that you were riding a big white horse —feet spread wide across the whole world— the Earth

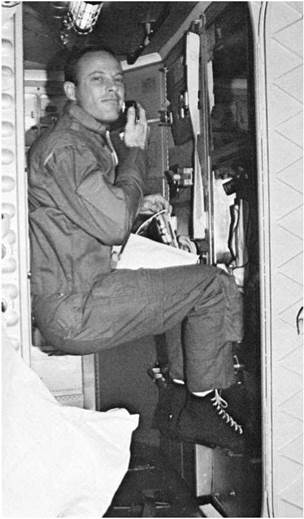

|

35. The Marshall Sail deployed on Skylab. |

is visible on both sides, at the same times and you can see 360 degrees—riding backwards.

Watching out the window as Jack worked in the dark; I could not look at him in the light as he was too close to the sun, it was fantastic to see the sunrise. It began as a light blue band which grew with a fine yellow rim near the limb—the blue gets larger then.

Just before sun up you could see flashes of light toward the horizon where thunderstorms were playing. This pinpointed the coming horizon which was not yet discernable against the dark of the Earth from within the lighted cabin.

Gold color grows in last 15 sec to change much of dark blue into bright orange. As the sun rises the Earth’s horizon slowly moves from head to toe on Jack as he is silhouetted against the blue line. It gives the feeling of going around a big planet, a big ball rather than just a disk movingfrom in front of the eye. The science fiction movie effect was fantastic.

And Garriott’s diary summed this all up with only five words: eva day — went very well.

Garriott, md-ii, 12,13:

Full atm ops. On 11, got a flare right off in ar8" Had been working that ar [active region] all orbit. Very fortunate.

MD-12, dble erep + more good atm.

md-ц, M-3 x-ray flare, well covered & then a 0-2 or-3 [a classification of intensity], all from ar8$. The last covered only by xuv Mon on vtr . Also a good s-063 [ozonephoto] w/erep in am, and s-o<;<; CalRoc successful! Vy good day, indeed.

Everyone in excellent spirits. Tomorrow is more or less “off day" but we’ll stay busy.

Can become disoriented w/ rapid spins. We all still feel some sense of up & down, related to orientation of i-g trainer & eqpt installation.

Fish orient “down" twd[toward] wall, usually and fairly quiet. But if “stirred up" a little & held in middle of room, still do outside loops, pitching down.

Fed both spiders today. Not sure if they will eat.

With the second crew’s Apollo Telescope Mount operations now well underway, the collection of instruments was producing groundbreaking results. The flares, for example, were very exciting for the crew to witness. These energetic outbursts on the sun showed up particularly strongly at ultraviolet and x-ray wavelengths visible to the observers on Skylab with their TV screens—because they were above essentially all of the Earth’s atmosphere —but not to ground observers. The ground saw the active regions (ars) in visible light and could direct the crew’s attention to promising locations on the solar disk, but unlike Earthbound astronomers the crew could see the first indications of an outburst from Skylab with ultraviolet and x-ray displays. The “CalRoc” Garriott mentioned on Day 13 was a coordinated observation of the same active region on the sun by Skylab and a rocket flight to high altitudes by the Harvard College Observatory experimenters.

The fish were part of an extra, small experiment that Garriott had asked to do well before launching, for the crew’s own interest. Arrangements were made by a veterinarian on the staff of the Houston space center, Dr. Richard C. Simmonds. The experiment included two small mummichug minnows and fifty unhatched eggs in a small plastic bag that the crew taped to a wall or bulkhead. The minnows had the strange, and quite unexpected, response to weightlessness of swimming forward but looping or pitching down. Watching the transparent eggs develop and the fry after hatching also proved interesting. Even the fry born in this weightless environment exhibited some of the same looping behavior. These observations eventually led to one scientific paper and later several more space experiments—and more scientific papers—on later Shuttle Spacelab flights.

Bean, md-ii:

Passed the lbnp today for the first time. Think I was too far in it and squeezed around stomach, cut off blood, will move saddle from у to 6.

Did a lot of flying about the workshop just before sleep tonight. Skill needed, but great relaxer.

Wish Owen would move Arabella. Arabella finished her web perfectly. When Owen toldJack at breakfast, Jack said “well that’s good, I like to see a spider do something at least once in a while".

md-12:

My green copy ofChildhood’s End floated by. If you wait long enough, everything lost will float by. A dynamic environment no one can be stranded in center of a space because small air currents have an effect.

Tried to fly (like swimming) last night. But air currents much more dominant.

Fire and rapid Delta p drill today. Owen needs this the most but hates them the worst. I tried to stick with him and do this together, Jack goes alone — when I am distracted, Owen will be doing other things not drill related and I must get him back.

Slept better last night (upside down) because it was cooler from the twin boom sunshade.

Arabella ate her web last night and spun another perfect one.

Garriott, MD-14:

Another good day! Houston reportedfilament lifting, got to (a Tm) panel as large loop was ~r=2.$ [extended out to a radial distance of about 2.3 solar radii]! Followed all the way out beyond R= 6. Excellent, I thought. Also made hemoglobin check (~іб-іб. у all three)… tv of Arabella, etc. Supposedly a “day off", but we made 4 atm passes, 3 s-oijops, etc. Back at it tomorrow! Also talked w/hm [Helen Mary, his wife] and family. Said flare was big news locally, w/scientists.

More than just “another good day,” Mission Day 14 was a history-making one for the Apollo Telescope Mount, which was used to capture an unprecedented image of the solar corona. One of the instruments on the atm, the White Light Coronagraph, would hide the bright face of the sun behind an “occulting” disk and image a superimposition of all of the visible light wavelengths in the corona. The sun’s very bright upper region, which is what is visible to the eye on Earth, is about one million times brighter than the faint corona, which can only be seen from the ground at the infrequent times of a total solar eclipse. On Day 14 the ground saw what appeared to be the start of a solar eruption at visible wavelengths and brought it to the attention of the crew, even though they were not manning the atm panel at the time.

“I got there in time to see what is now called a ‘coronal mass ejection,’ or cme, in progress, where the ejected material in the form of an enormous magnetic loop was moving out through the corona,” Garriott said. When he first saw the loop, its height had already reached about the width of the sun, and by its peak a few hours later, it was more than three times the sun’s diameter. “The radial extent of this giant magnetic loop could be measured on our TV screen. Then on the next orbit about ninety-three minutes later it was obviously stretched out much farther and it could be measured again. A simple calculation allowed the minimum speed of the ejection to be estimated, which turned to be about 500 kilometers per second! At that speed, it would reach the Earth in about three days. As far as I know this is the first visual observation of this phenomenon ever made.” Since coronal mass ejections can have a noticeable impact on Earth when they reach our planet, the groundwork laid on Day 14 toward better understanding them has had lasting benefits.

Garriott recalled getting immediate feedback on the day’s events during a phone call with his wife. “I had a telephone visit with the family at our home in Nassau Bay,” he said. “The wives brought us up to date on local news; for example, they told us that the TV reports and the solar scientists comments seem quite enthused about the ‘flare’ observations. It was our pipeline to the ‘real world!’ ”

Measured hemoglobin levels on all three crewmen had reached the upper end of normal, which Garriott suggested might have been due to the loss of water in weightlessness and a reduced total blood volume in circulation. Bean said that during his time on Skylab, he had to make a conscious effort

to avoid becoming dehydrated. “The thing that I noticed for myself is, I had to make myself drink water,” he said, “because I wasn’t thirsty then. And the next day I would have less energy. My urine volume would be low, and it finally dawned on me that I was getting dehydrated because I just wasn’t thirsty. So it got to where every time I came near the table, I’d take a drink even when I didn’t want it. And that helped. But I would fall back. After about four or five days of drinking water, maybe the fifth day I would not do it so much; I’d get complacent. Then I’d notice the sixth day that I got tired early, and then I would remember my low urine volume that morning. So I remember that as being a continual problem for me.”

In fact, Bean said during the entire mission, he had to make a conscious effort to stay in good shape and not allow his desire for productivity push him past the point of exhaustion. “Every day I remember trying to do as much as we could that day without hurting the next day,” he said. “I’d say to myself sometimes, ‘Uh oh, I worked too long,’ I was on the edge of fatigue each day at the end of the day. And if I didn’t get the sleep and food and water I needed, then I’d be fatigued the next day. I always felt like I was right on the edge, and I had to be really careful to keep myself healthy in order to do the next day the best I could, and feel really good all the next day, and be in a good mood. People get in a bad mood, I think, if they get tired and fall behind. We had good relations with Mission Control. In fact, our relations with Mission Control were great except when we wanted more work and couldn’t get them to schedule it for us.”

Bean MD-14:

Day off—we had mixed emotions. We were tired and needed rest yet our chance to do good work was almost one-fourth over. When each flight hour represents 13-14 Earth training hours then you can make (up for) a lot of pre-flight effort with a little extra in flight effort. We did however do some atm and some soip. We ask for extra. Plus housekeeping. Wipe, dry biocide wipe, the place is immaculate and not a predatory germ within miles, much less traveling at 18,000 mph.

Got a thrill today. Tried to put out a urine bag [through the Trash Airlock] with the end filter for the head in it in addition to three urine bags. It would not eject. I tried to close the doors and breathed a real sigh of relief as it came closed. I removed the filter from the bag and tried again, this time it moved 1” or so then stuck. I tried to close the door but this time it would not. My heart was beatingfast. Could this be happening to us. Could we not have a way to get rid of our garbage? I tried the ejection handle again, and no luck, the door was stuck. Finally the only way was to force it. I tapped it again and again at first no success, but finally a little at a time she broke free. The heart still beat fast but maybe a lesson was learned. Why did they not build the lock as an inverted cone so whatever was in there could always be moved down the ever expanding diameter.

Owen did the spider TV three times. Once because he recorded it on channel a, once because the TV switch was in the atm and not ows position, the last time it was okay. He got behind and I did some of his housekeeping as he was still up when Jack and I were headed for bed. Jack said “Owen, do you have anything left I can help you with". Owen said “no". But that’s the way Jack is.

Notice we do not seem to reflex to catch something when we drop it as we did the first few days. It’s enjoyable to just let a heavy object float nearby.

Garriott, MD-15-16:

Things beginning to ease up just a little. We’re considerably more efficient and flight plan may be a little less tight. Al now asking for more work (!)… All feeling excellent. Al doing lots of acrobatics (he’s good). Jack is walking around on the “ceiling”

Garriott was not the only one to feel that the crew was beginning to hit its stride around this time. Being as productive as possible had been one of Bean’s foremost goals for his crew from the outset, and the limitations they had faced early on had been a disappointment to him. He and the others had been working all during the mission to become more efficient, and around this time, they could tell they were getting close to the mark.

“We were in there working as best we could; and we were following the flight plan accurately; we were following our checklist, and as a result we were getting a lot of things done,” Bean said. “I felt like it took us until around Day 16 to really be as efficient as we ever could be. That was my feeling, and also looking at the data later on. We began to be pretty good at it.”

“So we sat down and had a crew meeting and decided that we needed to have an inventory from the ground as to where we were and what we had to do to catch up,” added Lousma.

Bean recalled: “Maybe at a third of the way through, or a fourth of the way through, we called the ground and asked how we were doing. I knew we’d fallen behind because of being sick, and I thought maybe they’d tell us we’d done 90 percent so far of what we should be doing. And they told

us we’d done 50 percent, 60 percent, something shocking. Well we knew we weren’t going to go back to Earth doing 50 percent. They will have to shoot us down because we aren’t going back till we’ve done the best we can do. We were going to find a way, and that’s kind of when we decided we were going to have to do things differently because we had to catch up, at least we all thought so. So we began to try to be more efficient. You know, we thought we were being efficient, but this motivated us to become more so.”

Every possible step was taken to increase efficiency. The crew stopped eating all of their meals together, so that two crewmembers could be working at all times. As soon as the crew woke up, someone would begin manning the atm station while the others went about their morning routine. Bean said that not long afterwards he realized that Garriott was the best of the three at manning the atm console, so he and Lousma began swapping duties with Garriott so that he could man the atm more.

The crew, and Bean in particular, began working to move items to and from storage during the day to reduce the amount of time that had to be spent on housekeeping. “We were working as much as we could,” Bean said. “We were really hustling around.” Finally, the crew reached a level of efficiency such that they were getting all of the work done that they had scheduled on a given day. But, having gotten behind at the outset, simply reaching 100 percent efficiency was not enough for Bean. “We began to try to get housekeeping done before it was scheduled, so we could say to them, ‘We’ve already got the trash thrown for tomorrow, we’ve already got the food moved, go ahead and put us on the atm,’ ” he said. “As I remember, we had to convince them to give us more work. We were ahead, and then they would call up and they wouldn’t have anything new the next day, and we would be twiddling thumbs. We were ready to go, but they hadn’t geared up for us yet. I remember us talking with them for about two or three days before Mission Control finally said, ‘ok, let’s give them a lot more work.’

“We then got going, and so we were just zipping around there as good as we could from wake up till rest before sleep. Because you can’t just stop working and go to sleep, we knew that you had to kind of take thirty minutes or an hour,” Bean said. “We were working all the time, except Sundays. Then we began to work Sundays after a while, because there wasn’t a damn thing to do, at least I felt that way. What are we going to do, sit around and just look? Not likely! We had trained hard for two and a half years, and we are going to make the most of our limited days, only fifty-six, in space. At least as much as we could. So we got going!”

Before long, the ground had to work to keep up with the crew. As Lous – ma recalled: “We got so good at what we were doing that it took so much less time than they had anticipated that we asked for more work, and that’s where they devised the Earth observations experiments: ‘Can you see this; can you see that; what can you see physically or visually from space?’ We would photograph those places and report on them. Every mission after that—I don’t know if they do it anymore, but Shuttle missions had Earth observations briefings and some special things to look for. So that was all derived as a result of our mission. They also jury-rigged some additional experiments using hardware that we had on board. They had some kind of experiment that had to do with transfer of fluids; it was not one we had planned to do. The point is they gave us extra work to do and things that we hadn’t planned on doing, so we actually ended up with more experiments than we started with.”

A major thing the crew had going for them, Lousma believes, was how well they got along. “I think our crew was somewhat remarkable in that we were such good friends,” he said. “We trained for two and a half years, and I don’t ever remember a cross word. I don’t remember one during the mission, or since.”

Even as the crew was becoming more efficient at their work, they were also becoming more efficient at their play. After over two weeks in weightlessness, the astronauts had become acclimatized to the unique acrobatics that microgravity allowed. “For an unusual experience, one could walk around upside-down on the ceiling of the laboratory area,” Garriott said. “It was fun to play ‘Spider-Man’ and walk around on the ceiling or elsewhere.”

While the entire crew had gotten their “space legs” by this point, it was Bean whose microgravity maneuvering was the most impressive. “I was amazed at how proficiently Al performed flips, twists, and other acrobatics while jogging around the ring of lockers in the ows,” Garriott said. “While Jack and I looked every bit the novices we were, only after inquiring did I find out that Al had been a gymnast in college! If only we could submit video instead of personal appearances, we might have had a shot at the next Olympics.”

The long straight layout of the pressurized volume of Skylab was the basis

of another amusement for the crew. “Another challenge,” Garriott said, “was to launch oneself at modest speed all the way from the bottom of the living and experiment deck and try to pass through the ows, the Airlock Module, the mda, and reach the csm without touching anything—a floating distance of some fifty feet with narrow hatches between each module. With practice we could all do it—sometimes.”

Bean, MD-i6:

Had a thriller, was writing in my book when caution tone then warning tone came on —Jack in the toilet—Owen and I soared up and found cluster att [attitude] warning lt [light] and acs [attitude control system light] on. We looked at the atm panel and found much Tacs firing andx gyro single, ygyro okay, z gyro single. A quick look at the atm panel showed multiple Tacs firings. Both Owen and I were excited, it had been some time since we practiced these failures, plus we are in a complicated rate gyro configuration—we both really were looking at all things at once—das [data acquisition system] commands, status words, rt[rate]gyro talk backs, momentum and cmg wheel position readouts. We elected to go a TT hold but Tacs keptfiring, so we then turned off the Ta cs, looked at each rate gyro and set the best one back on the line. We would have gone to the csm but with our quad problems that would be a true last resort. No, we had to solve it right then. We put the rate gyros back into configuration then enabled Tacs, then did a nominal momentum cage — this seemed to make the system happy — namely Tacs quit firing. Owen and I had settled down by then and were solving the problem again and again to insure we have not forgotten any step. We came into daylight— were only two degrees or so off in x and y so went to S. I. [solar inertial]— maneuvered too slow so we set in a five sec maneuver time and selected S. I. again—Houston came up and I gave them a brief rundown — Owen, never giving up time, started my atm run for me while I went down for dessert of peaches and ice cream.

erep passed today, Jack got four targets, we then had an erep cal [calibration] pass taking specific data on the full moon—all three of us working well together, we have trained a long time for this chance and we want to make the most of it.

Jack made a suggestion to walk on the ceiling as the floor for a few minutes —we did and in less than a minute it seemed like the floor although covered with lights, wiring runs and trays. Our home seemed like a new place—cluttered but nice — the bicycle hung overhead and was different as was the wardroom table but many lockers and stowage spaces were much easier to see and reach—I might use this technique to advantage when hunting a missing item or looking in a locker drawer.

Had to ask Capcom, Story Musgrave, to give us more work today and also tomorrow—we are getting in the swing— when you’re hot, you’re hot. We will have about 44 more days to do all the things we were trained to do for the last 2 V2—4 years — time is going fast and we must make the most use of it. Most of what we learned will have no application after Skylab—such as how to operate specific experiments, systems, where things are stored, experiment protocol, how to operate the atm, erep, etc.

The gyroscopes that allowed Skylab to maintain its attitude proved to be an occasional hassle. One failure of the gyros was particularly memorable for Bean, who committed a rare violation of procedure in the heat of the moment: “I remember the time we lost attitude hold. The alarm went off, maybe even in the night; I don’t even remember when it was. We had a procedure if it did, and I can remember not following that procedure. It’s one of those deals where you make [someone else] follow the procedure, but when you’re there, you don’t have to do it.”

Rather than trying to regain attitude control with the control moment gyros, Bean opted for the more immediate method of using the TACS thrusters, which had a limited, and unreplenishable, supply of cold gas, a large amount of which had been expended in the barbecue rolls before the arrival of the first crew. “I can remember not following the procedure and wasting some of the gas, wasting some of that to ‘zero out’ the rate gyros, instead of doing other things,” he said. “I can remember the ground didn’t say anything. Then later, about a day later, they came up with a new procedure, ‘just in case,’ which really was the same procedure, except, ‘Why would you guys do what you did?’

“At the time I threw that switch, I knew it was the wrong thing to do. It was too late then. It didn’t even seem right then, it just seemed like the expedient thing. We solved the problem quickly that way. But it wasn’t a good thing to do. I can remember me throwing that switch and thinking at the time it was a bad idea.”

Bean, MD-17:

Had bad experience today, sneezed while urinating— bad on Earth—disaster up here.

Did 10-15 minutes on dome lockers. Handsprings, dives, twists, can do things that no one on Earth can do —fantastic fun and I guess good limbering up exercises for riding the bike.

I went up and looked out of the mda windows that faced the sun, but at night. What an incredible sight, a full moon, Paris, Luxemburg, Prague, Bern, Milan, Turin all visible and beautiful wheels of light and sweeping under the white crossed solar panel of the atm. Normally you cannot look out these windows because of the sun’s glare, I could not watch Jack and Owen on their eva. Now we are over the Bay of Bengal. In just 16 minutes we swept over Europe and Eastern Asia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and finally over India. Too cloudy to see Ceylon [Sri Lanka]. Sumatra and Java will be here soon. We repeat our ground track every 5 days but 5 days from now as we go over the same point of ground the local time there changes so that in 60 days we will have seen allpoints between 50N and 50s at 12 different times of the day and night. At least once we can watch Parisians [Paris residents] getting up, having breakfast—

Owen and I spent his first night in ij days just looking out the window during a night pass. We came over places that aren’t our erep targets, the Dardanelles were visible, then he pointed out the Dead Sea, the Sea of Galilee—I said I had been as high as anyone on Earth and had visited the lowest point on Earth, the Dead Sea, last year. Owen talked ofthe night air glow—the fine white layer about a pencils width above the surface of the Earth.

We had looked last night for Perseid meteor shower with them burning up below us. Did not see any during soip — to hit the atmosphere, to make a shooting star, they all fly past us—with no meteoroid shield, hope we do not contact any one of them.

MD-i8:

Fixed my sleeping bag today, safety pinned on two top blankets and took up slack in blankets—too much volume of air to warm at night. Have been waking either around 1 to 2 hours prior to 6o’clock [normal wake-up time]. Houston time and having difficulty going back to sleep. Maybe this will help, sleeping upside down has helped, the cooler ows as a result ofthe twin pole sunshade deployment is perhaps the greatest contributor.

Normal morning sequence is wake up call from Houston, I get up fast, take down water gun reading, then put on shirt and shorts for weighing. Take book up and weigh while Jack gets teleprinter pads and Owen reads plan. I weigh, Owen weighs, then Jack. I fix breakfast after dressing, with Owen a little behind.

Jack cleans up, shaves, does urine and fixes bag and sample for three of us, I finish eating as Jack comes in and I then clean, shave and sample urine, I’m off to work at first job as Owen goes to the waste compartment. Jack is eating and about 30 minutes later we all are at work.

A sudden realization hit me this afternoon—there is no more work for us to do —atm is about it. Except for more medical or more studen t experiments what a sad state ofaffairs with this space station up here and not enough work to do.

We could think up some good TV productions getting 5000 watt-min of exercise per day and that should be enough.

Boy oh boy have I been farting today. You must learn to handle more gas up here and I wondered if we wouldforget when we went home. Owen said can’t you just see Jack in his living room with all his family and friends around and he forgets.

I am so glad that Owen and Jack and I are on the same crew. Our personalities fit one another well—Jack always working, always positive, always happy — Owen always serious, well maybe not always.

Owen looks funny lately as he has not trimmed his mustache hair nor shaved under his neck too well— our little windup shaver and the poor bathroom light being the problem. I don’t look too great either, my hair getting long, wonder if “O ” or Jack will cut it on our day off

Owen got his ego bent last night. He had been conscientious about weight loss, wanting more food, and salt—peanuts are a favorite, Dr. Paul Buchanan called on his weekly conference and told Owen, [that] Jack and I were doing okay but he needed to have a chat with him [Owen]. Paul said, Owen, we have been looking at your exercise data over the last two days and don’t think you are doing enough, maybe your heart isn’t in it—Owen about flipped because he takes great pride in his physical program pound for pound he does more than Jack and I. He could hardly hold back, afterward he worked out till sweat was all over his body, then called on the recorder to tell Paul and those other doctors the facts of the matter. Maddest I’ve seen him in months. [Garriott explained that it turned out the ground had not yet read the data off the recorder, and the issue was smoothed out later.]

As Bean noted, the sleeping bag modification referenced at the beginning of this entry was the second major mod he made to his “bed.” The sleeping quarters were designed in such a way that an air vent would cause air to flow from the feet to the head when a crewmember was sleeping in the bed.

Bean found it difficult to sleep in that configuration and unstrapped the cot from the “vertical” bulkhead where it was mounted and inverted it so that he was sleeping “upside-down” compared to the other two astronauts. Garriott noted that while Bean’s modification to invert his cot worked fine on Skylab, where each crewmember had his own “bedroom,” it could have been more problematic if the station had been designed with the three sharing one larger area since it could be disconcerting to carry on a conversation for any length of time with someone in a different body orientation.

Near his upside-down bed, Bean kept a sign posted on the inside of a locker door, which he made a point to read at the start and end of each day, and which thirty years later he still says was an important part of his life on Skylab.

A man is what he thinks about all day. “The only time I live, the only time I can do anything, the only time I can be anyone is right now.

Each hour we have in flight is the culmination of approximately 12 to 13 preflight hours (1У2 days). These hours well spent are our only tangible product for literally years of work and preparation.

Our doubts are traitors and make us lose the good we oft might win by fearing to attempt.

Did we enjoy today.

Ask for questions.

Importance of the individual.

Write in my crew log.

Garriott, MD-i8:

Not enough to do today! Al doing most of HK [housekeeping tasks]. Mentioned to Al— he agreed— that often when “sitting" still with eyes closed, there is an apparent sense of motion. Sort ofslow vibration (2 or 3 second oscillation), back and forth… Maybe body is actually perturbed slightly by air draft, but I think not. Does seem to be a vestibular “false motion."

Brightflashes occasionally. Always dark adapted. Believe have seen with eyes open. Usually spots, not necessarily pin-points. Occasionally a longer streak. Only one eye at a time.

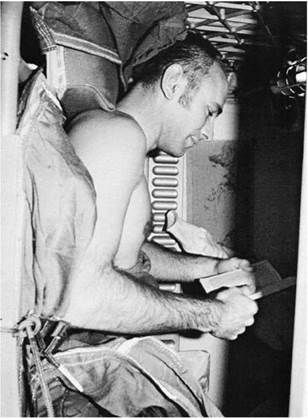

The odd body oscillation Garriott noted he later determined was probably real motion caused by each stroke of the heart pushing arterial blood out through the body. The crew’s vestibular systems were probably unusually

|

З6. Bean reading in his bed on the wall of his sleep compartment. |

sensitive to any body motion as the large gravitational acceleration could not be sensed in free fall.

The bright flashes of light were explained later as passage of an energetic particle through the retina creating a flash that the crew could see. It almost always seemed to occur when Skylab was near the South Atlantic Anomaly where the Earth’s magnetic field is a bit weaker than at most locations, and trapped energetic particles can dip down to lower altitudes like that at which Skylab orbited. The phenomenon was not isolated to Skylab—oth – er astronauts since have also reported seeing bright flashes while crossing through the anomaly.

Bean, MD-19:

We have been trying to get the flt [flight]planning changed. I especially have

had a lot of free time, Owen and Jack to a lesser degree. Jack keeps on the move all the time, Owen has a long list of useful work that he brought along, things that other scientists have suggested, worthwhile. How do I accomplish this feat of us producing our maximum without infringing on Owen’s time. He deserves some amount per day to do with as he chooses.

In a way space flight is rewarding but on a day to day it is awfully frustrating. Jack today spent whole night pass takingstar/moon andstar/horizon sightings on his own time to satisfy an experiment. When the pass was over, 20 marks made, he was debriefing and as he was talking he said, well, I did those sightings with the clear window protector still on. He had not noticed it in the dark. The data would be off by some small amount and that just didn’t suit Jack. He told the experimenter on record that he would repeat them later.

Teleprinter message: To Bean, Garriott and Lousma

We have been watching and listening as the three of you live and work in space. Your performance has been outstanding and the observations that you are making are of tremendous importance. Through your efforts Skylab 3 is a great mission.

Keep up the good work.

Signed,

Jim Fletcher [nasa Administrator]

George Low [nasa Deputy Administrator]

Received this today. Why do they not send something similar when we are not doing too well, like days 2-4. We appreciated this but just wondering not only about them but about myself.

Went to bed on time, do not feel as energetic as usual so feel something was coming on. Sleep is the best thing to repair me, it always works on Earth.

Bean, MD-22:

Our first real day off Best news was in the morning science report where it said we would catch up with all our atm science as well as the corollary experiments except for medical which was reduced by 24 hours the first half of the mission, we would do the rest—I called and discussed the additional blood work, histology and urine analysis [specific gravity] that Owen had been doing and wanting them to count that.

We did housekeeping a bunch and had to plan two tv spectaculars. Since we have a Tm all day we had to schedule it in the 30 min night time crew rest. Hair cut next, then acrobatics, then shower. Lots of planning for 3 ten min shows but think the folks in the old USA will enjoy.

The shower was cooler than I like it— the biggest surprise was how the water clung to my body—a little like jello in that it doesn’t want to shake off It built up around the eyes, in the nose and mouth (the crevices) and it gave a slight feeling oftrying to breathe underwater— would shake the head violently and the water would drop away (not down but in all directions) some to cling to other parts of my body, some to the shower curtain, some sort of distended the water where they were and snapped back. The soap on the face stayed and diluted with rinse water tasted sour when I opened my mouth. The little vacuum has sufficient pull but is rigid and will not conform to the body—so does not do too well there, but is okay on the inside walls, floor and ceiling. Jack had said it was better to slide my hands over my body and to scrape the water offand over to the shower wall. This worked for hair, arms, legs, but difficult for my body especially back — two towels were required to dry off because the water did not drain.

MD-23:

Flew T 020 for the first time. Jack as usual had the dirty work but was trying harder because of his error yesterday. The work was slow and tedious because it was the first time around and because the strap design was poor.

Jack said ‘I’ve done some pretty dumb things in my life but I never got killed doing it— in this business that is saying a lot’—

Owen said “now the dumbest thing I can remember was flying out to the (solar) observatory near Holloman, nm—short hop so I decided to do it at 18,000 ft— as I neared there I started letting down, called approach control— we talked and as I descended their communications faded out—I kept thinking why should they fade out— it suddenly dawned, shielded behind mountains —full power and a rapid climb in the dark saved my ass—I think of the incident several times every month over the last three years. ”

Garriott recalled, “I thought I had never mentioned this to anyone, anywhere, since it was such a dumb thing to do. I had forgotten about this one time in Skylab. I had worked all day on atm things in Boulder, Colorado, that day, then drove to Buckley Field in Denver, to fly solo by T-38 to Holloman afb and work the next day at the solar observatory in Cloudcroft. A beautiful clear night, stars but no moon. When I heard approach control at the airport, I started down. dumb! When their voices started breaking up and then faded out, I asked myself why. When realization came quickly —mountains!—it was maximum power (burner) and steep climb until I heard their radio transmissions again with no further problems. I have continued to think about this incident frequently for the next thirty-five years, but it is so embarrassing that I have never admitted it to anyone — except on this one Skylab occasion!”

Bean’s diary for that day continues:

Jack was saying that when we got back he and Owen might be considered regular astronauts — Owen laughed— it was beyond his wildest dreams to be classed as a real astronaut.

Been wishing Owen and I had taken pictures of the Israel area the first time we stayed awake to see it—I want to give pictures of this region to some of my religious friends.

Jack’s having his ice cream and strawberries. Jack’s food shelves when we transfer a 6 day food supply are almost full of big cans plus a few small— Owen and I have halffull shelves with more or less equal amounts of small and large cans —Jack really puts down the chow.

All are in a good mood, morale is high in spite of all the hard work, we are getting the job done.

MD-24 A tough, tough day. Worked almost all day on trying to find the leak in the condensate vacuum system—hundreds of high torque screws, stethoscope, soap bubbles, tfpsi nitrogen, reconfiguring several pieces of mo equipment— we never found the leak—that effort must have cost $2.4 million in flight time.

Owen got this word that the citizens of Enid [Oklahoma, his home town] would be putting their lights on for him to see—I went up with him—it was the clearest, prettiest night we’ve had— we could see Ft. Worth-Dallas particularly —a twin city, one of few — then Oklahoma City then Enid then St. Louis then Chicago — Owen made a nice narration. He said started to say he saw Tulsa up ahead and realized it was Chicago. Paul Weitz said that was the one thing he never became accustomed to on his flight— the speed which you cover the world, especially the U. S.

This was not quite the end of the story, however, as Owen heard more about the incident following his next conversation on the family private communication loop. It turns out his wife, Helen Mary, also raised in Enid, felt she had to call the radio and TV stations in Enid and try to explain how Owen could be so thoughtless as to not even mention their major citywide effort to be seen directly by him.

Perhaps his predicament was best explained by Alan’s comments on Mission Day 35 after most of the fuss was over: “That night we both went up to see the lights of Enid—he talked of Mexico, Ft. Worth, Dallas, here comes Tulsa, look at St. Louis, Chicago—everything but Enid—Helen Mary called up there and tried to soothe the people—she gave Owen hell—I kept telling him to say something about Enid; they had a direct TV hookup, radio hook to us and all lights including the football field.”

“That’s been an embarrassment to me ever since,” Garriott said more than three decades later. “In fact, I undoubtedly saw Enid, but because there were so many lights all across the area, I wasn’t certain just which ones were from Enid, and by the time I thought I had it figured out, we were past Chicago, less than two minutes later.”

Bean, MD-26:

Owen reported an arch on the uv monitor in the corona yesterday. We called it Garriott waves to the ground— he was in the lbnp and was embarrassed and told us to knock it off— we were happy for him. Today he heard the ground could not see it in their taped tv display — he went back and checked and found it to be a sort ofphantom or mirror image of the bright features of the sun except reflected in the camera by the instrument. He’ll get over it (maybe that’s why he was distant).

Crippen woke us this morning with Julie London singing“The Party’s Over." Jack wanted to make this Julie London Day, so did Crippen so he could call her but Owen won out with Gene Cagle Day [who played a major role in the atm development at msfc].

MD-27:

Would you believe it we get better н-alpha pictures at sunset than we do at sunrise because our velocity relative to the sun is less and that effectively changes the freq[uency] of the filter in each н-alpha camera and telescope—not a small item either.

Owen’s humor—I said “watch your head" as I pulled out the film drawer. Owen replied “I’ll try but my eyeballs don’t usually move that far up."

We were laughing about this malfunction (“mal") we had after we discovered

the water glycol leak—I wanted to call Houston and say “Jack is working on the cbrm [charger battery regulator module] mal, Owen on the camera mal— tomorrow after we fix the door mals, the у rate/gyro mals and the nylon swatch mal, I’ll start work again on the coolant loop or the water glycol leak mal. ”

Everyone feels better about eva—I worry too much and Jack will pull it off. Funny how easy it looks now that we are going to do it—did it get easier as we understood the plan or did we just want it to be doable? Morale is high—did perfect on my mo 92/iji (medical experiments).

Mission Day 28 brought the crew’s second spacewalk. Like the first spacewalk of the mission, the second would include an extra task to repair a problem with the station. In addition to the routine task of changing out the atm film canisters, the eva crewmembers would also install a cable for the six-pack gyros.

The Skylab’s attitude, or orientation, control system relied on two sets of gyroscopes. The large Control Moment Gyroscopes were used to torque the whole Skylab to a new attitude or hold it in position. A set of smaller attitude control gyros was used to monitor the attitude of the station. These smaller gyros had proved erratic since the station’s launch, and while they continued to function, the decision was made to activate a new six-pack of gyros on the second eva in hopes of providing improved attitude control.

During the four-and-a-half-hour spacewalk, the two astronauts changed out the atm film cassettes and left two samples of the material used for the parasol outside to be recovered on a later eva so that the effect of exposure could be monitored.

In the days leading up to the spacewalk, Bean found himself having to make a difficult decision—who would go outside and who would stay inside? The original mission plan had called for each of the three astronauts to get two turns at an eva, and the second was to be performed by Bean and Lousma. Bean’s diary captured the decision-making process for who would go on the eva :

Bean, MD-24:

Heard tonight we may put in the rate gyro 6pack—I told Owen [that] Jack & I would do it because they did the twin pole and because that sort of work fits my skills better than Owen’s—hope it did not hurt his feelings but that is the way I see it and that’s my job — Owen even brought it up by saying “I think you want to put out the 6pack and that’s okay with me—I’m glad to do it but know you want to"— I said you’re right we don’t need this job but ifit comes up we will pull it off.

MD-25:

Today was a special day —found out we were going to put in the rate gyro pack — who to do it— Owen still wants to do it and so do I. Made up my mind that it would be Owen and I but after reading the procedures realized that I should stay in because ofmy csm experience — Owen and Jack are just not up on it and it is the best decision —Jack will do the 6pack as he is the most mechan- ical-Owen does not do those things as well as Jack, it will be taxing to tell him tomorrow—I was awake about two hours trying to put the pieces together and think Owen and Jack outside — me inside is the best way.

MD-26: