Pete: “Very good.”

The next day’s erep pass was canceled. Houston realized that there would be no more full passes until and unless the workshop solar wing was freed. Work on that continued with determination. But morale remained high.

Houston (8:30 p. m.): “. . . One of the things we were wondering is, have you learned to ride the portable fan yet?”

Pete: “No, that’s next. We’ve got to master the front and back flips while running on the water ring lockers.”

Mission Day 7 started out on a relaxed note.

Houston: “Skylab, Houston. I’ve got some sad news in this morning’s paper that the blob is dead. I’m sure that Joe will be glad to hear that. And they killed it with nicotine. (Laughter.)”

Joe: “I’d like to be the blob.”

Houston: “Getting to feel it now, huh?” [Not smoking.]

Joe: “You guys are all going nuts down there.”

Paul: “We’re going nuts up here too; the cdr thinks he can fly.”

Houston: “The Astros won a game yesterday, 4 to 1.”

Joe: “Hurray! Are the Cubs still in first place?”

That morning Pete took the Sound Pressure Level Meter out of stowage and toured Skylab, taking measurements. It was a quiet spacecraft. The levels in the workshop averaged between forty-five and fifty decibels. The Multiple Docking Adapter returned a reading of fifty-three (the level of a quiet office), and the noisiest compartment was its aft end, the so-called Structural Transition Section leading into the Airlock Module, where the pumps and fans registered sixty-two.

The other noise characteristic of Skylab was due to its atmospheric pressure, five pounds per square inch, one-third of an atmosphere. Maybe you’ve hiked high enough on a mountain to notice that up there where the air is thin, sounds are diminished. Skylab was at the equivalent altitude of Mount McKinley, above twenty thousand feet; the silence was eerie. One had to raise one’s voice to be heard by someone ten feet away. Between the workshop and the Multiple Docking Adapter voice communication was impossible; the crew used speaker/intercom boxes to communicate. The good side was that you could play your own music at, say, the Apollo Telescope Mount control panel (each man had his own cassette tape player) and not interfere with the music down in the medical experiment area, where by agreement the subject got to pick the tape.

All three crewmen tried and tried again during their daily exercise periods to conquer the bicycle ergometer — adjusting the harness tighter or looser, changing the angle of the floor straps, raising or lowering the seat. Nothing worked. Weitz attempted M171 again on Day 7, but the problem hadn’t been solved.

It was still taking too long to do things; the crew was still behind the timeline. Calibrating the Body Mass Measurement Device had Kerwin an hour and a half behind by noon. Houston wanted Weitz to reinstall an experiment. He said, “Okay. Is that in my flight plan?” Houston said yes and Paul said, “Oh, Okay. I hadn’t read that far ahead yet. I’m still trying to catch up. Sorry.”

Pete expressed their frustration this evening:

Pete (6:30 p. m.): . . You guys are slipping things into the pre and post

sleep activities every day, without adding the time. We’ve already given up shaving in the mornings, and we do it at night after 0300 [ 10:00 p. m.]. And your time estimates for small activation tasks have turned out to be completely wrong. . . . Handovers take time. . . . I had alarm clocks going off in my pocket, and if you’ll look back over my plan, I’ve been whistling all over this spacecraft today.”

Neither crew nor schedulers had yet caught on to the secret. The first time you did something complicated in weightlessness, it took twice as long (or longer) than it had in training. The second time was faster. By the third or fourth repetition, you were back to the preflight estimate. But things were getting better. And the next day was Day 8, the first scheduled “day off.”

Pete (8:13 p. m.): “I would like to add one thing, Dick. I think tomorrow, rather than a day off, it’s going to be a field day. We’ve got an awful lot of cleaning up to do in here.”

Later, Paul had a request. “Say, Dick, awhile ago we asked for the coordinates of the Pyramids . . . and tomorrow’s our day off. I’d also like the coordinates of Mt. Kilimanjaro, if you can find them.”

Houston said ok and good night.

Pete: “Yes, we’re all shaved and we’re leaving for the party. . . . Good night, Dick!”

Unburdened by medical or solar physics duties, the crew did spend much of Day 8 (Friday, 1 June) cleaning up and restowing. They also did some sightseeing out the window, three noses pressed to the glass, three pairs of legs out in different directions. As an aid to where they were, they had a map of the world marked with latitude and longitude lines and pasted onto both sides of a big piece of stiff cardboard with slick plastic rollers at each end. Stretched over the map was a continuous piece of clear plastic, marked with a curved line representing Skylab’s orbit, inclined fifty degrees to the equator; and on the line, short cross markings at intervals of how far Sky – lab would travel in ten minutes.

On request, Houston would give them the exact time and longitude where Skylab had last crossed the equator from south to north—its ascending node. They’d slide the plastic overlay to match, and following the line from there in ten-minute increments, they’d see where they were and what was ahead. For example, set the slider to cross the equator at 160 degrees west longitude, due south of Hawaii. The orbit line showed that Skylab would cross the U. S. west coast at San Francisco, speed over southern Canada north of Montreal, leave America between Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, fly southeast over Spain and right down the African continent out into the Indian Ocean east of the Malagasy Republic, up into the Pacific between Australia and New Zealand, and back close over Hawaii—all in ninety-three minutes.

During that hour and a half, the Earth would have rotated one-and-a- half twenty-fourths of 360 degrees, or twenty-two and a half degrees, which at the equator is about 1,350 miles eastward. So the ground under Skylab’s windows would be different each revolution. So would the time of day, the lighting and the weather—a thousand permutations to look for, and the greatest world tour imaginable. Hundreds of frames of film were used on clouds, ocean, islands, mountains, hometowns.

Paul (11:30 a. m.): “Hey, pass on to the people that we are sure glad we came up with this big Earth slider map we’ve got. It’s been the most used single piece of gear on board.”

But a good deal of thought was also going into a TV special for Houston and America. At ten after two:

Houston: “Skylab, Houston, with you for about fifteen minutes.”

Joe: “Okay. Let us know when you get the picture.”

Houston: “It’s good now.”

Weitz cranked up the volume on his cassette recorder, and the strains of “Also Sprach Zarathustra” by Richard Strauss—the theme from the movie 2001—filled the air. Pete, Paul, and Joe floated up from the experiment compartment into the upper workshop doing their best imitations of swimmer and movie star Esther Williams. They twisted and rolled; they flew from wall to wall; and as the climax of their show they ran around those ring lockers in an exercise they dubbed—what else—the “Skylab 500.”

Joe: “Pete’s got a couple of free style maneuvers here. The difficulty of that one was a 1.6. Here’s a 2.2 (laughter). He didn’t get many points for that one. . . that was a new one even on us. That’s it. Can we show you anything?”

Houston: “Story wants to know if you’ve gotten around to a handball game yet.

Joe: “No, not yet.”

Houston: “We’ve just had offers from Ringling Brothers Barnum and Bailey and Kubrick both, if you can bring that show down to Earth and do it.”

Pete: “Everybody’s adapted super well. We all got to talking about what’s going to happen to us when we get back to Earth, because the first thing we’re going to do is dive out of our beds in the morning and crash on the floor.”

On the afternoon of Day 8, the crew had a surprise call about the stuck solar panel from Deke Slayton, the Mercury astronaut who was the corps’ “big boss.”

Deke: “Okay, Pete, this is Deke. I’m sort of playing the middle man between you and Rusty. He’s over at Marshall trying to work some procedures on this thing, and he has a couple of questions. . . . As a starter we’d like to know if there’s any daylight anywhere between that strap and the beam.”

Pete: “. . . I’d say a half to three-quarters of an inch.”

Deke (after more conversation): “Okay. We’ll keep working the problem down here and keep you advised. You guys are doing great work. Hope you’re having a nice day.”

Pete said they were. It’s always nice when the boss is happy with your work.

Deke: “When you have another spare minute you might pull out that wire bone saw—that’s Rusty’s favorite tool. And try it on something around there; you’d be surprised how well that beauty works. And I guess that’s still his favorite choice to solve your problem.”

Pete: “Okay; we’ll do that. We also talked about the possibility of us putting the suits on inside the vehicle and seeing how much purchase we can get on—something around here like a food box, you know. . . and see how well we could hang on. . . .”

Deke said ok and signed off.

The field day gave both crew and Mission Control teams a chance to catch up and apply some lessons learned. At 7:30 p. m. the crew reported that once again, most of the coffee on the menu wasn’t drunk. “Coffee isn’t going over too well in the subtropical climate, you can see,” remarked Paul. Later, Pete had another first to report.

Pete (9:05 p. m.): “We’ve had one through the shower, one in the shower and one waiting for the shower.”

Houston: “What does the one that went through it think of the shower?”

Pete: “He’s clean and sweet and smelling good right now. That’s Commander Weitz. [One might notice the crew usually got Weitz to try something first.] And we’ve got Joe in there right now, and we’re timing him to see how long it takes. It takes quite a while to sop the water back up again.”

And so to bed.

Saturday, 2 June, Day 9, was Conrad’s birthday (his forty-third), and he talked briefly with his wife and children that morning.

The crew’s increasing efficiency and Mission Control’s increasing experience with scheduling finally dovetailed; the crew finished on time. In the evening report, Pete said, “There were no flight plan deviations today. And we thought today’s flight plan was excellent.” Did the crew’s performance have anything to do with adaptation? Kerwin thought it did. He remarked, after the flight: “I didn’t get motion sick early, just a little less appetite. But Day 8 was the first time I woke up in the morning and said to myself, ‘I really feel great today.’”

A little extra time for Earth gazing was appreciated:

Pete: “I just got some good pictures of Bermuda with the 300 millimeter camera for the guys in the tracking stations down there. . . . And it’s a lovely day down there. And with the 300 millimeter, the girls look very nice on the beach.”

Houston: “Come on, Pete, you haven’t been up there that long. Your eyes aren’t that sharp yet.”

Joe: “He even thinks Weitz looks good.”

That evening Houston gave an update on the eva plan. “There’s a big management meeting scheduled on Monday to evaluate all the work that Rusty’s been doing down in the tank and to formulate several options. And we’ll send up the results to you for your evaluation. Then we’ll mutually settle on an eva plan and go from there. There is no eva planned for Tuesday.” Pete said ok. They were getting closer.

One more modest first was recorded that evening:

Pete (10:00 p. m.): “We broke out the first ball tonight about 20 minutes ago. We had a little pitch game going, the three of us. And then we turned it into a kind of football game—ricocheting off the walls and throwing a few passes. So we’re working up a few dynamics and orbital mechanics for the ball.”

Houston: “I can’t say I’ve really got a little bet going, but there has been a discussion going as to whether you can really throw the ball straight the first time. Did you?”

Pete: “Yes, it goes straight as an arrow.”

Houston: “Amazing. We always thought you’d throw it high without the gravity there.”

Sunday, 3 June could truthfully be described as a normal working day in space—with the overtone of increasing attention to the forthcoming eva.

Houston (6:15 a. m.): “Skylab, Houston. Do we happen to have anybody in the area of the STS [Structural Transition Section] panel?”

Joe: “Don’t be coy, Houston. What do you need?” [They wanted a switch position checked.]

Houston (7:20 a. m.): “And for the cdr, I’m informed that you now hold the record for more time in space than any other man around, namely Shakey.”

Pete: “Holy Christmas! You mean I finally passed Captain Shakey? I can’t believe it.”

Houston: “I think you’ve got him beat by a long way before this thing’s over.”

Pete: “Send him my regards while he’s off on his tugboat.” [“Shakey” was Jim Lovell, an old friend of Pete’s and commander of Apollo 13.]

At 9:00 a. m. Joe played the Navy “Church Call” from his tape cassette for Houston. And later, he recorded on в Channel his evaluation of handholds: “Okay, the Workshop dome and wall handholds are adequate for their jobs, maybe even give them a ‘very good.’ Their job is not to handover-hand it—you never do that around this place, unless you are carrying a large package. You ordinarily fly from one location to the next, and all you need when you get there is something to grab onto.” The science pilot was obviously getting used to flying; a couple of weeks later he wrote his wife a poem about it.

On Sunday evening, the Capcom was Story Musgrave, Kerwin’s backup and very good in a spacesuit.

Story: “We’re planning on an eva this coming week to deploy sas panel number one. . . . Next evening we’ll send up some procedures for you and also talk them over with you real time to a limited extent tomorrow. Tuesday evening we’ll have maybe two or three revs [orbits, more or less] discussing the procedures with you, including probably a TV conference. . . .”

Pete: “A TV conference. ok. You guys happy you worked something out over there, huh Story?”

Story: “Yes, it’s looking pretty good. . . . It’s basically a five-pole extension with a cutting tool on the end of it and grabbing hold of the strip on the end of the sas wing, tying down the near end to the fixed airlock shroud, and this will give you an eva trail going out there.”

Pete: “Very good. We aim to please. We’re more than happy to do anything we can.”

To make it easier to follow the story as it unfolds, here’s an overview of the eva plan Rusty’s team had developed: Once the airlock’s eva hatch was open, Conrad (outside) and Kerwin (inside) would assemble five five-foot – long aluminum poles into one twenty-five-foot pole—long enough to reach from the nearest accessible point (the A-frame) to the sas cover and the strap that held it down. On the business end of the pole would be a telephone company limb lopper (referred to by the crew as the “cutter”). Two ropes from the cutter’s handles (pulling one closed the jaws, the other opened them) would be strung back along the pole to the near end. Kerwin would egress the airlock and proceed around to the A-frame; Conrad would hand him the pole, then follow him around.

Kerwin would maneuver the pole so that the cutter’s jaws slipped over the offending strap, then pull the right rope to close the jaws. The jaws would bite into the strap but not yet cut it. Kerwin would tie the near end of the pole to a nearby strut, forming an “eva trail” down to the sas. Now Conrad would move down the pole, hand over hand, until reaching the sas. He would carry another rope, known as the “bet” (short for “beam erection tether”), which had two hooks on its end. Kerwin would hold on to the other end of the bet.

Being careful to avoid cutting his suit on sharp edges, Conrad would fasten the two hooks into ventilation openings on the sas, down past its hinge.

|

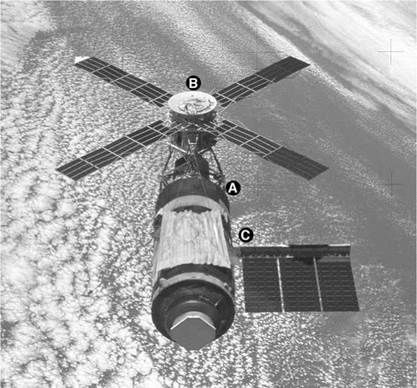

2.6. From Skylab’s airlock (A, hidden in this picture behind the Fixed Airlock Shroud, the black band at the far end of the workshop), an EVA—path provided access to the sun end of the atm (B). However, there were no translation aids going toward the solar array (C). |

Kerwin would then tie his end of the bet to a beam as tightly as possible, so that it would lie nearly flat along the surface of the ows. Kerwin would close the cutter’s jaws all the way, severing the strap.

Conrad would then wriggle his body between the bet and the workshop surface and “stand up.” Kerwin would try to do the same up at his end. Together they would put tension on the bet, exerting a pull force on the sas beam. The engineers figured it would take a couple hundred pounds of force to break the frozen hinge and free the solar panel.

On Mission Day 11 the crew produced a swing and a miss and a home run. The swing and miss occurred during another Earth Resources pass — not with the full maneuver so as to preserve precious battery charge—but a valuable pass, and it went well. The only problem was that after the pass, Pete, reading the checklist, told Paul, “Close the S190 window cover.” And Paul

said, “It’s already closed.” And then both of them said, “Oh, dear, [or some word like that] — we forgot to open it.” The S190 experiment included a set of six cameras which used a high-quality optical window. To keep the window pristine, it was protected by a cover at all times except during a pass. On this pass those cameras took photos of the back of the door instead of the Earth.

They immediately confessed to Houston and constructed a new cue card written in big black letters with that and other key steps on it and posted it over the Earth Resources switch panel. Its title was “Skylab 1 erep Dumbs—t Checklist.” They never forgot again.

The home run was the breakthrough on how to ride a bike in space. On Days 9 through 11, the crew perfected the secret to riding the bike. The secret was taking the harness, wrapping it into a bundle, and throwing it away. Then they just hung on and pedaled. The body tended to pitch forward because the handlebars didn’t extend back far enough, so some arm fatigue resulted. They found that letting their rear ends float away from the seat and their heads press against a couple of towels duct-taped to the ceiling as a headrest helped ease the strain on their arms. And they didn’t actually put the restraint harness down the Trash Airlock. They were tempted but ended up returning it to its stowage locker, where it would come in handy in a different role on the third mission. The breakthrough was complete; exercise to full capacity was now possible.

But on the ground, medical management was coming to some very conservative decisions. Dr. Chuck Ross, the crew Flight Surgeon said, “The Skylab medical team was conditioned to be concerned about irregular heartbeats in space because of their occurrence on a couple of Apollo missions. On Apollo 15 isolated premature ventricular beats had been observed on both lunar surface crewmen [Dave Scott and Jim Irwin], and Jim had had a series of coupled irregular beats during return from the moon. There was little the doctors could do during the flight. Postflight analysis led to the conclusion that loss of fluids and electrolytes during the strenuous lunar surface evas had caused the problem. [There was a suspicion that the men’s habit of taking long runs on the beach before launch had also cost them some electrolytes.] Extra potassium was added to the Tang for the next flight [John Young, the commander, complained about the taste] and several drugs were added to the medical kit to treat severe heart rhythm disturbances if they occurred. None did.

“But when, on Day 8, the team saw Pete’s premature ventricular contractions from his Day 5 M171 run, their concern increased. The Skylab 1 medical team was headed by Dr. Royce Hawkins, a ‘by the numbers’ man with little tolerance for risk and a stickler for procedure. Dr. Chuck Berry, the chief astronauts’ physician for the Apollo program, had left for a headquarters assignment and was not involved day-to-day in Skylab. And the senior physician at jsc, the very well qualified Dr. Larry Dietlein, was ill.

“During the day both Pete and Joe had described the modification to the ergometer to Houston; and Joe recommended letting the crew run the exercise experiment again at the flight-plan levels. But Royce decided that he could not risk a serious arrhythmia occurring in an unmonitored crewman during exercise. And he was prepared to give a no-go for the upcoming eva unless he received assurance that the crew could exercise safely. That was the background when I was directed to relay Royce’s decisions to the crew.”

Late on Day 10, the crew had received a teleprinter message directing them to eliminate the top levels on their bicycle ergometer exercise runs. The teleprinter was a typing device with heat-sensitive printing on a three – inch strip of paper that could be up to thirty feet long. Messages arrived every morning with the day’s plan for each crewman, procedural changes, instrument settings, and so forth. And at the Day 11 medical conference, the crew flight surgeon, Dr. Chuck Ross, reluctantly relayed another decision to the crew. From now on, no free exercise was allowed. All use of the ergometer was to be fully instrumented with the twelve-lead electrocardiogram and had to take place when Skylab was flying over the United States, so that the surgeon could watch the heartbeats in real time. This procedure would make it much harder to schedule exercise and less would be accomplished, but the doctors were not going to take a chance. And Pete’s permission to perform the eva was to be conditional, depending on his ergometer run on Day 12.

Conrad took immediate action. He requested another private teleconference with Dr. Kraft and told Chris in the most positive terms that the ergometer modifications had solved the problem and the crew had to have free exercise. He got the decision changed, as long as the ergometer run on Day 12 with him as the subject went well. It did. That reversal and its result removed a potential roadblock to the imminent spacewalk and had a lot to do with allowing Skylab 11 and ill to proceed to set new duration records.

Why was Conrad so passionate about exercise? Kerwin explains: “Both before and during the mission, Pete told us the story of his first try at joining the astronaut corps, along with the Original Seven. During medical testing at the Lovelace Clinic, he received a surgical examination that he considered to be unnecessarily rough and brusque—and called the offending doctor on it that evening at the Kirtland Air Force Base Officers’ Club bar. Pete was disqualified medically from that selection as being ‘not psychologically adapted for long duration space missions.’ He was selected with the second group, and you could say that his subsequent astronaut career had as at least one of its goals to prove that doctor wrong. He wanted Skylab to be a success, and he wanted to walk off that spacecraft after twenty-eight days in good shape. It was, and he did.”

Houston was true to its word. At 9:33 and 25 seconds on Monday evening, Rusty started his discussion. Three sets of data came up that night on the teleprinter while the crew slept, to review Tuesday and a lengthy, detailed discussion took place Tuesday evening. The crew went through a dry run in the workshop Wednesday morning with TV coverage of part of it so they could show their equipment to the folks on the ground and discuss how to use it. Wednesday evening, the crew would start the eva prep, getting all the setup tasks they could out of the way—so that they could get a nice early start Thursday on the spacewalk. And Rusty assured them that if they needed more time, delaying until Friday was ok too.

Rusty then went into a detailed walk-through of the plan, using a diagram of the workshop previously sent up on the teleprinter. The crew mostly listened. When Rusty got to the part about standing up under the rope to break the damper and pull the beam hinge free, Pete remarked, “ок. I hope it don’t pull too hard, or we’re going to get swatted like by a fly swatter.” Rusty replied, “No — we’ve done it a lot, Pete, and it’s kind of fun as a matter of fact. You’ll enjoy watching it come up.”

The astronauts didn’t go outside cold. They had a very detailed discussion Tuesday evening with Rusty and Ed Gibson and then stayed up late preparing the equipment. On Wednesday morning, they did an “eva Sim” in the workshop, the best dress rehearsal they could do inside of what they were going to do outside. They cut and spliced lengths of rope, sewed cloth containers (“Pete did the sewing; he was a real sailor,” Kerwin noted), connected aluminum poles together with the cutters on one end and a place to tighten the rope on the other. Kerwin put his spacesuit on — minus the hel – met—and practiced moving the twenty-five-foot pole around and grabbing

something with the cutters. (The floor triangle grid was used as a test target.) The dress rehearsal was as they say Broadway dress rehearsals often are—messy and filled with surprises but very productive. They discussed the details on the air to ground.

Joe: “Can we use the discone antenna as a handhold?” [That was a large radio antenna which stuck straight out from the workshop near the astronauts’ work area.]

Capcom: “You can put something like—four feet up—forty pounds or so. Okay, we also—I don’t know if you’ve had a chance to practice with the bone saw, but we’ve got identified for you a piece of 7075 aluminum inside, and that was the launch support bracket. Feel free to cut through it. The only precaution is—you want to have a vacuum cleaner sitting right on top of it, so you don’t end up with aluminum chips.”

Pete: “ok.”

Rusty: “Pete, let me continue on the strap. . . after you cut the strap, we expect, because of the frozen damper situation, that the beam may rise about four degrees before you really put any tension in the bet. . . also, a recommendation after cutting the strap and when you get down there to play the human gym pole game, getting under the bet to push up on it. . . it’s very important that when the beam first starts to give, and you can feel it in the bet, you want to slack off so as not to put any additional energy into the beam coming up.”

Pete: “ok.”

Rusty: “Just for safety reasons, it’s a good idea, when you feel something break, to just stand back and let it go.”

Rusty: “We see the doctor getting into his suit. We wonder if he’s going to try to go out today?”

Joe: “No. I want to get a halfway feel for the difficulties of handling that 25-foot pole.”

Rusty: “Okay. We think that’s a good idea, Joe.”

Pete: “Tell me another thing. Just how do you get yourself under the

BET?”

Rusty: “Okay. . . after the beam is free, what you do is, using that rope as a trail, you just move back above the hinge line and just work your way underneath the line. It’s not that tight. There really is no problem. And as soon as you get underneath it, as you begin to raise up, you put compression

on yourself. And so it’s quite natural to be able to stand up and the rope holds you down nicely against the beam fairing.”

Pete: “ok. Now the pin by the discone antenna. If you are looking aft, minus x, the discone antenna is on the right about nine inches away, sitting in an angled channel, isn’t it?”

Rusty: “That’s very good, Pete.”

Pete: “Okay; we can see it from the window — the STS window.” [The Structural Transition Section—the lower portion of the mda—had four small windows.]

Rusty: “Ah, that’s great. We never even thought about that. . . . A precaution. . . at the base of the discone antenna there are two coax connectors which provide the signal path, and Joe wants to be careful not to mash those connectors.”

Joe: “Okay, about those connectors. It’s obvious that there’s a risk that they’ll be damaged or broken off. . . .”

Rusty: “We recognize that, and all we’re asking for is reasonable prudence on your part, Mr. spt. . . . One thing for you, Pete. The folks down here have looked at the optimum place to put the vise grips on a flange of the pcu [the spacesuit’s Pressure Control Unit in the chest area of the suit]. . . .”

Pete: “Joe and I figured we’d put them on the blue hose.”

Rusty: “Okay. We really didn’t have any use for those vise grips out there, Pete. We figured they were just a pretty generally useful tool. . . .”

Pete: “Yes, we agree.”

And back and forth for nearly three hours. From the transcript, it’s clear that they felt a little skeptical about their chances. Near the end of the sim, Joe said: “That’s right. I guess we’ll know better when we see it, but our initial impression is that we’ve got a fifty-fifty chance of pulling it off. And then even if we don’t, we’ll have a fine reconnaissance for you and some real good words on techniques and possibilities for another try later on.”

Rusty: “Right, that’s just the way we figure it except we’ll give you a higher probability.”

Pete: “Yes, well. Just let me caution you. There is no doubt in my mind, as you mentioned, that we could get involved like we did in Gemini 11. And if we do a lot of flailing around out there, I’m sure that we can run out of gas pretty easy. So I think you’d better figure if we’re unsuccessful in the first

hour and a half we’re probably not going to get the job done. . . but we’ll give her a go tomorrow. I’m pretty sure we understand everything. We’re going back and smoke them over and talk about it some more. And I think the biggest thing depends on Joe being able to get the pole hooked on to something. There’s number one, and two—either cutting it or me cutting it or however that works. And let’s hope there isn’t something else holding it besides that strap.”

Rusty: “Yes, sir. . . .”

The day proceeded with normal activities, eva preps and last-minute decisions. Pete decided not to try bringing the TV camera outside on the eva—too much complexity, another long cable to contend with. (As a result, there are no good pictures of the eva.) The doctors on the ground let Ker – win take the night off from wearing his electroencephalograph sleep cap, so he’d get a good night’s sleep before the eva. Everybody— on Skylab and in Mission Control—went over all the checklists one more time with the usual last-minute changes. Pete’s comment: “You got 500 guys down there keeping three of us busy.” And a little later: “It’s like the night before Christmas up here. The suits are hung by the fireplace with their pcus in place, just waiting to go.”

Power was important. The additional power load imposed by the eva had to be balanced by turning things off. Here’s how Houston summed it up:

Houston: “And all this [the shutoffs] comes to 1,100 watts. And then the things that are required for your eva—all your lights, sus [Suit Umbilical System] pumps, tape recorder and converter, primary coolant loop and pcu power, comes out to about 887, and then vtr [videotape recorder] is another 125 for a total of 1,012.”

Joe (petulantly): “ok. We noticed that little note not to use the food heaters for lunch tomorrow. I’ll have you know that we’ve only been using the food heaters for one food each day, and that’s the evening frozen item.”

And here’s a sample of the news for that day, 6 June, as read up to the crew by Capcom:

I’ll start off by saying on this day in history, 1944, we landed in Normandy. President Nixon’s made several new appointments this week. . . . General Alexander Haig will retire from the Army to become Nixon’s assistant in charge of the

White House staff. Haig, as you recall, was former assistant to Henry Kissinger. . . . Vice President Spiro Agnew spoke to the U. S. Governors at the National Governors Conference at Stateline, Nevada. Agnew told the audience that he was ‘available for consultation.’… In Paris, Henry Kissinger resumed secret talks with Le Duc Tho, Politburo member from Hanoi. The two representatives are seeking ways to halt continued violations ofthe ceasefire in Viet Nam. The Senate Watergate hearings continue to be televised during the daylight hours. .

.. A bill has passed the House to raise the minimum wage from $1.60 an hour to $2.20 an hour next year…. Brigette Bardot announced that she will retire from film making. “I have had enough,"she was quoted as saying. Some baseball scores from yesterday: Philadelphia 4, Houston 0, Dodgers 10, Chicago 1. . . .

Talking about Watergate on the air-to-ground was a sensitive business for the Capcoms. Weitz said, “Good sense of proportion. Good night, you all.”

“The day of the crucial spacewalk dawned bright and clear,” according to Kerwin. “But since we had a bright, clear dawn approximately every ninety – three minutes in Skylab, there was nothing special about the way this one looked. There was a slight air of unreality again—sort of like launch day; you know what to do, but you don’t know what’s going to happen. Both the spacecraft and the control room were quiet and businesslike. There wasn’t any hurry. We had the checklists and were methodically working them off, staying a half hour early.”

Pete: “Houston, CDR.”

Houston: “Go ahead.”

Pete: “Oh my gosh, is this Rusty?”

Rusty: “That’s affirmative.”

Pete: “You better give us—what’s the earliest time we can start, Rusty?”

Rusty: “Okay. You’ve got a sunset right around 1410. Hold on, I’ll get an exact time.”

Pete: “Okay. I’m not sure that we’ll make that but there’s—we’ve kind of got a leg up on things and just depends how fast it goes. Otherwise we’ll cool it to the right time.”

Rusty: “Okay, we understand. And we’re sort of semi-prepared for that. Let me give you an exact time here, Pete. Okay. The prior sunset time is about 1403. And Pete, for positive id purposes we’d like just a word of confirmation that you’ll be playing the role of ev-i today and that Dr. Kerwin will be playing the role of ev-2.”

Pete: “That’s Charlie.” [Playing off the commonly used “Roger” confirmation.]

Rusty: “Charlie, Pete Conrad.”

The crew didn’t make the one-rev-early start time for the eva; there were problems with the coolant loops aboard Skylab that kept Paul occupied and held the two eva astronauts back. But they had time.

Joe Kerwin said, “Paul helped us don the suits. It seemed harder than usual to get snugged in and the zipper zipped. On the ground we were usually able to zip it ourselves; up here much pulling and tugging was required. It wasn’t till much later that Dr. Thornton explained to us we’d grown a couple of inches taller.

“Helmets and gloves were secured with a series of satisfying clicks, and checked. The oxygen we were now breathing smelt cold, metallic, and good. Moving to the airlock had been a terrifyingly clumsy task when we practiced it in the big Huntsville water tank. Here it was easy, pleasant, a cakewalk. We’d pulled our long umbilicals out of their storage spheres in the airlock, ‘down’ to the workshop where the suits were stowed for donning. Now we carefully pulled the excess behind us as we floated ‘up’ and in; everything had to fit in those tight quarters.”

Paul went ahead of them. The Skylab airlock was right in the middle of the cluster’s layout. Aft was a hatch into the main workshop; forward were the Multiple Docking Adapter and, right on the end, their Apollo Command Service Module taxicab. Paul had to move to the forward side of the airlock; once it was depressurized there’d be a vacuum between the workshop and the safety of the Apollo, and no way for him to cross it. Before he left his two crewmates, he made sure they had all the gear they’d need: pole sections, cable cutters, ropes, and spare tethers. Gray-taped to the front of Joe’s suit was Rusty’s favorite tool, the wire bone saw from the dental kit in its cloth container, just in case. Suit integrity checks were performed, and at a quarter past ten it was time to get on with it. It was Pete’s prerogative to open the depressurization valve and let the air out of the airlock. Even that wasn’t routine:

|

27. A rare photograph from the solar array deployment spacewalk. |

Pete: “Houston, you may be interested in knowing that on the airlock dump valve, a large block of ice is growing, on the screen [a small mesh screen to keep debris out of the depressurization valve].”

Houston: “That on the inside, Pete, or on the outside?”

Pete: “On the inside. Must have enough moisture in the air, Rusty, that as it hit the screen, it froze. That’s what’s making the lock take so long to dump down.”

Pete finally scraped off some of the ice with his wrist tether hook, the airlock got down to 0.2 psi, and the hatch was opened at twenty-three minutes after ten.

Pete went out first and got his boots into the foot restraints just outside the hatch. Joe started assembling the twenty-five-foot pole, pushing it out

to Pete as he did so. At 10:47 Houston was back in communication, and Pete gave them a status report: “We have five poles rigged swinging on the hook. And we’re just intrepidly peering around out here deciding how far around Joe can get in the dark. Now, the pole assembly went super slick. I had a little juggling problem getting the last longie with the tool on it. . . but she’s all rigged and ready to go hanging on the hook here.”

Inside Paul was having trouble getting a source of cooling water to his suit. (He was suited just in case Pete and Joe, when finished and back inside, couldn’t close the hatch.)

Paul: “Hey, Pete?” [To Don Peterson, the Capcom.]

Don: “Go ahead, Paul.”

Paul: “Yes, I’m ready to start working on getting some cooling water, if you think you got a way.”

Don: “ok, P. J., we do have a way to do that for you. Are you ready to copy?”

Paul (who is suited, helmet off): “No, I’m not. Can you just tell me?”

Don: “Yes, okay, forget that. Are you ready to listen?”

Paul: “Yes.”

But, outside, Pete and Joe were admiring the view.

Pete: “Look, there’s half a moon—”

Joe: “You can see the lights, you can see the moonlight on the clouds.”

Pete: “Oh, I can see the cities, yes.”

Joe: “Horizon to horizon.”

Don: “Hey, can you guys stop lollygagging for just a minute so we can get a word to Paul?”

The next ten minutes were a medley of Pete and Joe pulling out fifty-five feet of umbilical for each and solving the resulting tangles, interspersed with Paul talking to Houston about cooling pumps.

The route to the solar panel was uncharted territory. To get there, the crewmen would have to move underneath the Apollo Telescope Mount struts to reach a point at the edge of the Fixed Airlock Shroud where those struts were anchored, a point the crew called the “A-frame.” From there they could look straight aft at the stuck Solar Panel 1. And that was as close as they could get. There were no handholds, no lighting, no eva accessories out there.

Pete: “I tell you, you’re going to get worn out doing the things that require you to go there. Do it. Well, that’s a big snarl down there. I hope it all comes out right.”

Joe: “Now I suggest you take that loop in your hand and put it up over your head.”

Pete: “No. How did we do that? . . . Okay. That all right?”

Joe: “Yes. And it all goes behind you.”

Houston: “Joe, are you going through the trusses or up over the top? You should be going through them.”

Joe: “Through, through. I’m right on the mda surface.”

Houston: “ok.”

Joe: “I’m looking at Paul through the window right now. The other window, Paul. Hi there. I’ve got one hand on the handrail, one hand on the vent duct, and I’m looking at the discone antenna.”

Pete: “Do you see the pin?”

Joe: “I’ll tell you—no, the base of the antenna is pretty dark.”

Houston: “The next thing you’ll be doing when you get enough light is to go up and hook your chest tether into the pin.”

Joe: “Understand.”

Houston: “And for your information, you’ve got seven minutes to sunrise.”

Skylab sailed out of communications range at eleven minutes past eleven. When Houston regained contact over the United States at nearly 11:30, Pete and Joe were well into daylight. Their struggle with the aluminum strap, the twenty-five-foot pole, and Newton’s third law had begun.

Getting into position had been easy. Kerwin was floating beside the discone antenna, loosely tethered to the pin at its base (an eye bolt shaped like an upside-down u). He held the twenty-five-foot pole in both hands and had it pointed aft, right down the left edge of the Solar Array System, with the cutter’s jaws tantalizingly close to the plainly visible villain of the piece, the aluminum strap. Conrad was just above and behind Kerwin, holding with one hand to one of the sturdy beams that supported the Apollo Telescope Mount. All Kerwin had to do was move the jaws (each about four inches long) over the strap and clamp them tight.

When Houston came back into communications range over the United States fifteen minutes later, Conrad and Kerwin were still struggling. Here are some excerpts:

Pete: “Okay, Houston, we’re out there. We have the debris in sight. There looks like enough room to get the cutter in, and I’m trying to help Joe stabilize. And Joe, you’re way past it, it looks like.”

Joe: “I don’t think I am.”

Pete: “Yes you are. Come—come towards me.”

Joe: “. . . See, I’ve got it tethered, and that prevents me—”

Pete: “You’re battling the tether. [The tether securing the pole to the structure, to prevent them losing it if they lost their grip.] . . . I’ll re-tether it for you. Can you hold the pole?”

Joe: “I’ve got the pole.”

Pete: “Got it. Now you’re in business.”

Joe: “I’ll tell you, holding that on there is going to be a chore. Goldang it. Wait a minute. . . . If you could hold one foot, man, I could use both hands on this.” [Whenever NASA uses a word like “goldang” in an official transcript, the actual word used may have been a different one.]

Rusty: “Okay, we’re reading you. Understand you’re having trouble maintaining your position in order to hook it on the strap. Can you give us a little more detail?”

Pete: “. . . We’re working the problem. Bunch of wires in the way. Gosh, that prevented you from getting it that time.”

Rusty: “Okay. The only thing I can say is that in the water tank we stood almost parallel with the discone with our feet down by the base, and used the discone as a handhold.”

Joe: “Yes, I’m doing that. It’s not a handhold I need, Rusty, it’s a foothold.”

Pete: “I tell you, Rusty, it looks like if we ever get it on the strap we’ve got it made. Because I can see the rest of the meteoroid panel, and most of it’s underneath and looks relatively clear.”

The pair kept on struggling. But when Houston went out of contact at 11:44, they still hadn’t clamped the strap. They called a halt for rest and thinking. And while he was resting, Kerwin looked down at the base of the discone antenna, at the eye bolt where his chest tether was fastened. And he had an idea.

The chest tether was six feet long and adjustable. Kerwin said, “What if I just double the tether? Instead of hooking it on the eye bolt, I run it through the eye bolt and back to my chest? And tighten it a little so I can stand up against the tension, sort of a three-legged chair, two feet and the tether?”

Pete helped run the tether through; Joe clicked it onto the ring on his chest and stood up. He was as stable as a rock. Three minutes later the jaws were closed on the strap. Houston came back at 11:54.

Rusty: “Skylab, Houston, we’ve got you through Vanguard here. Sounds like you got it hooked on somewhere.”

Pete: “Yes we do, and now all we’re trying to do is straighten out the umbilical mess before I go out.”

Rusty: “Great.”

Pete: “I don’t think we’ll have to move the cutter. We’ve got it in the thinnest spot. All right, you ready?”

Joe stabilized the pole and Pete went out hand over hand, his legs out sideways to the left, his end of the Beam Erection Tether tethered to his right wrist.

Pete: “Let it come over the end first. Don’t pull it all loose. That a boy. Bye.”

Joe: “Take your time; I want to feed this rope behind you.”

Pete: “I’m going to tighten the nuts on these pole sections on the way. . . . Every single one of them has backed off.” And there was a lot of straightening of umbilicals. Houston unfortunately was going out of communications range again—with things looking up, but the issue still in doubt.

Rusty: “Okay. . . we’re going to have an hour dropout before we pick you up again at Goldstone. That’ll be at 1803 [three minutes after one Houston time.] And you have about thirteen minutes of daylight left. And no big sweat.”

For a moment it appeared Pete’s umbilical, now pulled out to its full sixty feet, wasn’t long enough. But he and Joe straightened it out and it was. Pete could only get one of the two hooks on the bet fastened to the Solar Array System beam; the opening for the other was just too far away to reach. Joe tightened and tied the near end of the bet; it now stretched from the hook on the sas beam to the A-frame strut. Pete carefully inspected the jaws of the cutter; they were perfectly positioned.

Now Joe positioned his body parallel to the pole and pulled on the jaw

closing rope with all his might. The jaws closed, the strap was cut, and Pete was a bit startled as the sas beam jumped out a few inches, then stopped. This was just as predicted. Pete inspected the area; the beam was free, the damper was frozen, and the hinge would have to be pulled open.

Pete carefully backed away, six feet or so toward Joe. Carefully, the umbil – icals were pulled back and straightened, with care to make sure that one didn’t get pinched. Carefully, both men moved their bodies under the bet, feet toward the solar panel, face toward the workshop surface.

Kerwin recalled, “Pete gave the word and we both pushed away with our hands and got our feet under us. We pushed and straightened up. Suddenly —I almost remember hearing a ‘pop,’ but I know I couldn’t have heard one. I guess I felt the pop. The rope was loose, and we were free in space, tumbling head over heels and floating away. Then I got hold of my umbilical, and pulled myself back down till I could grab a strut and turn around. And so did Pete. And we saw the most beautiful sight I’ve ever seen—well, almost. That solar panel cover was fully upright—ninety degrees from the workshop — and steady — and you could see the three solar panels inside it beginning to unfold. Touchdown! When I think about it now, thirty years later, I can still feel that glow.”

Rusty (three minutes after one): “Hello there. We’re listening to you. You’re coming in loud and clear. And we see sas amps.”

Pete: “All right. I’ll tell you where we are. We’ve got the wing out and locked, the outboard panel and the middle panel are out about the same amount, and the third one is not quite. Got the main job done.”

Conrad and Kerwin spent quite a while inspecting the area, tidying up their ropes and discussing everything with Houston. Back at the hatch, they stopped to push Pete’s umbilical back into its sphere inside the airlock —about the most physical work they’d done on the eva. Then Joe got a reward. He got to move up the eva trail to the sun end of the Apollo Telescope Mount to inspect the doors, pin one open, and replace film in one of the cameras. It was a treat to work where handholds and footholds were plentiful—and a real treat to stand up above the atm with sun overhead and the Earth spread out below, beautiful as ever, its roundness apparent. It was a “king of the hill” feeling.

The hatch was closed a little under four hours after egress.

Rusty: “Okay, I got some good news for you. First of all, everybody down here is shaking hands, and we wish we could reach up there and shake yours. That was a dandy job and everybody was very pleased. And secondly, we’re saying press on with the normal Post eva Checklist where it says ‘eat.’ Go ahead and have a nice one and just cool it.”

Pete: “Yes, roger. When we have time this afternoon we’ll debrief the eva. I can tell you where the differences are between the water tank and up here. That’s why it took us longer.”

Rusty: “You got the job done. We don’t care.”

Pete: “Well, we got the job done only for one reason, and that’s because Joe asked for the end of the long tether to double it up to get himself anchored. If he hadn’t been able to anchor himself we wouldn’t have been able to do it.”

Later in the afternoon, this exchange took place.

Houston: “Skylab, Houston, how do you read?”

Joe: “Well, the plt is shaving and the cdr went by and said, ‘You’ve been a good boy this week, Paul; you can have the Command Module tonight.’” [The orbital equivalent of a paternal loan of an automobile to reward a teenage son.]

Houston: “Roger, copy. Everyone listening up?”

Paul: “Yes.”

Houston: “Okay, I got a message I’d like to read up to you. It’s to Sky – lab Commander Conrad. ‘On behalf of the American people, I congratulate and commend you and your crew on the successful effort to repair the world’s first true space station. In the two weeks since you left the Earth, you have more than fulfilled the prophecy of your parting words, ‘We can fix anything.’ All of us have a new courage now that man can work in space to control his environment, improve his circumstances and exert his will, even as he does on Earth. Signed, Richard Nixon.’”

And that is one of the legacies of Skylab.

The crew thought their day was over, but it wasn’t. At about 8:oo p. m., when they were doing final cleanup chores and looking out the window, Houston had cheerful news: “We’re showing them [the solar panels] all three ioo percent, and we’re starting to command you back to solar inertial at this time.”

But an hour later, there was this call:

Houston: “Okay, let me get with you guys on a problem we’ve been watching here, which is the secondary coolant loop. [It] got very cool during your eva, and we can’t seem to get the devil warmed back up. . . . As you know, the primary loop we can’t use because of the stuck valve. . . what we’re looking into now is what critical items we can turn off tonight so that we don’t have to be waking you up.”

The crew rogered, and signed off as usual at about 10:00 p. m. The men were tired. There wasn’t much window gazing this night, just quick trips to the bathroom and a few minutes’ reading in “bed.”

But they were just getting into deep sleep when Houston was back.

Houston: “Hey, sorry to bother you guys, but this coolant loop is getting away from us. It’s down to two degrees below freezing now. And we’re going to have to get you up and work on it until we can get the thing warmed up. . . . It may freeze up in the condensing heat exchanger, and that’s an intolerable situation. Sorry to do this to you guys. . . .”

Pete: “No, we want to keep the show running, pal. Don’t worry about that.”

It was an ironic situation; in a spacecraft plagued by heat, an essential system was threatening to freeze. And what saved the situation were those warm workshop walls that the parasol didn’t quite cover.

Here’s what was happening. The airlock coolant loop consisted of two circulating “loops” of fluid driven by pumps. In the interior loop the fluid was water. It flowed through pipes in metal “cold plates” to which electrically powered devices were attached, cooling them, and during spacewalks, through the eva umbilicals to the crew’s suits and into plastic tubes in their undergarments. After being warmed by the astronaut’s bodies, it flowed through a heat exchanger where its channels were in contact with those of the exterior loop. The exterior loop contained a water/glycol mixture, antifreeze, with a low freezing point. It warmed up in the heat exchanger, taking heat from the water, then radiated the heat to space in an external radiator.

The problem was that the airlock and Multiple Docking Adapter had been cold throughout the mission, and much of the electrical equipment had been turned off because of the power shortage. When Pete and Paul did their spacewalk even more equipment had been turned off, enough to cool

the loop further despite the heat transferred from the astronauts. The external loop’s temperature dropped dangerously. If it dropped below the freezing point of water, the glycol wouldn’t freeze but the water would, rupturing the heat exchanger and making the loop inoperative.

The crew scurried into the workshop, found umbilicals and two of the liquid cooling garments (lcgs) normally worn under their spacesuits to circulate cold water around their bodies and hooked them into the coolant loop. Then they taped the lcgs to the warmest part of the workshop wall they could find, near Water Tank i. They turned on the pumps, flowing water into the loop, warming it. They covered the lcgs with clothing to prevent heat from being lost into the atmosphere. They and Houston powered up every piece of equipment on that loop. They were thankful for the power newly available.

And it worked. Temperature at the heat exchanger rose to forty-one degrees in just under an hour. The crew stayed up until midnight, to make sure Houston had it under control, then went back to sleep, weariness mixed with relief. Houston promised not to wake them until 8:oo a. m.

The coolant loop emergency marked the transition between the first and second halves of the Skylab I mission. With reveille on Day 15, both crew and team were relaxed and confident, schooled in their roles and determined to “get back on the timeline.”

Systems were powered up. There was hot water for the coffee. Hot showers began to appear on the flight plan (but only once a week). Skylab talked to Houston about the possibility of scheduling another spacewalk to erect a better sunshade, the so-called “Marshall Sail.” They decided to leave that to the second mission; but the crew unanimously made the decision to substitute Weitz for Kerwin for the end-of-mission film retrieval eva on Day 26. All three had trained, and spreading the experience around would be good for the astronaut cadre.

Suddenly it was the second half of man’s longest space mission; everyone was now thinking ahead to its conclusion. Houston negotiated a plan to shift the crew’s workday several hours earlier, starting with Day 21. The big shift was made necessary by a nominal landing at dawn in the Pacific, and crew and ground agreed it would be easier to take it in little steps. The steps weren’t that little. They shifted earlier by two hours on Mission Days 21 and 22, then by four and a half hours on Day 28, their last night aboard

Skylab. Pete and Paul each took a Dalmane sleeping pill that “night,” but nobody got much sleep.

Days settled into a routine. Had there been a murder on Skylab, and had Hercule Poirot wanted to check everyone’s whereabouts on the crucial day, he’d need only to refer to the air-to-ground conversations and the telemetry data showing what was on or off. Medical experiments were “down below,” and the subject got to pick which music tape to play. More busy passes at the atm, including usually an evening pass. Earth Resources passes daily for six straight days. Somehow the crew started keeping up and getting ahead. On Day 17, Pete actually settled into his sleep compartment at 9:30 with a book. “Yes,” he told Houston, “We ran out of things to do.” Houston answered, “You better be careful, Pete. I saw three guys reach for 482s [a task form] down here to start scheduling.”

They began to look for activities not in the flight plan.

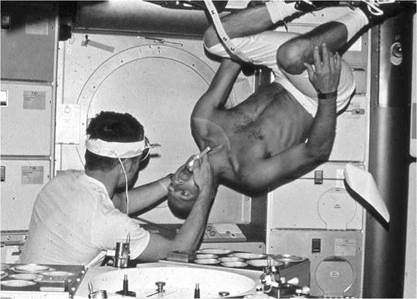

Kerwin, on Day 18: “I have my hobby up here. I have my do-it-yourself real doctor kit. Right now I’m staining slides.”

Conrad: “He’s working on my throat culture or something.”

Pete invented new games involving the blue rubber ball.

Pete: “We’re working on a new game up here, Houston. It’s called ‘get the rubber ball back to you.’ Try it off the water ring lockers first.”

Houston: “Which ball you using, Pete?”

Pete: “The blue rubber one, but—it gives up energy awful fast. It kind of poops out after four or five bounces. What we really need is one of those super balls.”

Paul, on Day 19: “Roger, Houston. We’re pretty busy right now. The cdr is trying to break the plt’s world record of thirteen bounces around the ring lockers. . . . Don’t ask for the rules. It’s extremely complicated, involves orbital mechanics and everything.”

Houston: “Just be sure it’s only the world’s record that you break.”

On the evening of Mission Day 22, the crew gathered around the wardroom table for ice cream and strawberries around bedtime, and somebody said, “It’s been Day Twenty-two up here forever!” Now that routine had taken over, just a little boredom had crept in. They were starting to think about coming home.

The very next day, Houston discussed with the crew the possibility of their staying aboard one extra week, to complete additional experiment runs. Of course Conrad said, “You betcha, Houston—we’re ready!” But all three were just a bit relieved when the idea was dropped, as NASA gained confidence that the second and third missions would take place. This crew was ready to smell the sea air.

As the flight went on, Pete developed an unfortunate addiction to the butter cookies. He was exercising hard and needed the extra calories. And the butter cookies were “homemade” — done in a NASA kitchen to the recipe of Rita Rapp, a wonderful food system specialist. It got so bad that on Day 23 he asked Houston specifically to assure that there were plenty of butter cookies aboard Ticonderoga, the recovery aircraft carrier.

One evening the three decided to check out what it felt like to navigate around a big spacecraft in absolute darkness. They turned off every light in the workshop and covered the big wardroom window, then waited for the spacecraft to fly into night.

“It was really different!” Kerwin recalled. “I never had a sensation of falling till we did that. But you were absolutely clueless about where you were and where anything else was. It was scary. I just clutched my handhold and didn’t want to move. It was my first real sensation of fear in space. And others have reported similar feelings. I remember Ken Mattingly talking about emerging from the Command Module hatch on the way home from the moon on Apollo 16, to retrieve film from a camera in the Service Module. Neither the Earth nor the moon was in sight; space looked like an infinitely deep black hole. He just wanted to hold on to something.”

All three crewmen had their twentieth college reunions going on. All of them asked that greetings be relayed to their classmates.

Most evenings the Capcom would have time after the evening report to give the crew a brief news report. There was plenty of unrest on planet Earth:

Houston: “The Texas wheat crop is expected to be the third largest in history, but it’s in danger because of our fuel crisis. . . . They’re limiting gas at lots of places to ten gallons per fill-up. . . . Nixon is proposing a new Cabinet level Department of Energy and Resources. . . . There was a partial brownout of all Federal Buildings in Washington DC. . . . Nixon has established a price freeze for sixty days, and is considering a profit rollback. The markets didn’t like it; the dollar was down and gold was up.”

“There were seven inches of rain in Houston yesterday. . . . Dr. Kraft [the

|

28. Kerwin performs a medical examination of Conrad. |

center director, who lived a few miles west of the center in Friendswood] is spending the night at the Nassau Bay Motel.

“President Sadat visited Libya to discuss the planned merger of Egypt and Libya. . . . General Francisco Franco, now 80 and ruler of Spain for 35 years, is turning part of his duties over. . . . The war in Viet Nam may be nearing an end. . . .”

“A Soviet TU-144 crashed at the Paris Air Show yesterday. There were many deaths. . . .”

“In case you’re going to South Padre Island, Texas, they have just elected a new sheriff who’s a 27-year-old redheaded mother of two. She says, ‘I’m a mean redhead, and if they ever call me ‘pig’ they had better be careful.’”

Paul: “I think we’ll stay up here, Houston.”

Houston: “Come to think of it, maybe you people are well off where you are.”

Also on Day 22, there was “The Flare.” For days, the sun had been tantalizing the crew with hints of increased activity. The crew got daily briefings on what was happening. They sounded like this: “Active Region 37 has rotated onto the disc. . . as a large spot group. And we had a subnormal flare there which began at 8:35. . . .”

The briefers hoped to alert the Apollo Telescope Mount operators (and all three crewmen shared that duty) to where a flare might occur. It was the Holy Grail of solar physics to capture a flare—especially the first crucial minutes of rise—with the variety of instruments onboard Skylab. It would be historic data. Each of the Skylab solar experiments had its own team of investigators. But since just one astronaut would operate all of them during a single fifty-minute sunrise-to-sunset “pass,” the investigators had gotten together to plan a large number of Joint Observing Programs—jops—designed to handle all their various data needs during all levels of solar activity. And the granddaddy of jops was the infamous jop 13, the routine for a solar flare. It required quickly and accurately pointing the Apollo Telescope Mount canister straight at the flare, then activating all the cameras in high speed mode with correct settings. It took lots of photographs; film was flying through the cameras. jop 13 was not to be used lightly—scientists wanted desperately to get a flare, but nobody wanted to waste film on a false alarm.

How could there be a false alarm? The views and instrument readings that the crew had available had never been used this way before, so the “signature” of the beginning of a real flare wasn’t known. As the mission progressed, it seemed that the best clue to a real flare was going to be an increase in x-ray intensity measured by one of the two x-ray telescopes. But another phenomenon also caused the x-ray count to increase—a trip through the South Atlantic Anomaly.

One of the first discoveries ever made by an orbiting spacecraft was made by Dr. James Van Allen, using data from a simple Geiger counter on America’s first satellite, Explorer 1. He discovered two “belts” of solar radiation trapped above the Earth by its magnetic field. The inner Van Allen belt consisted of energetic (and dangerous) protons. Its center was about one thousand miles up, but at one point, just east of the southern end of South America, it dipped close to the atmosphere. That is the South Atlantic Anomaly. And Skylab passed right through it, not on every revolution, but a few times each day. For example:

Pete (on Day 18): “I have an in and out on the flare there, Houston; 650.” [A reading of 650 on the proportional counter.]

Pete (a minute later): “Want us to go after the flare, Houston? It’s 690, 700.”

Houston (after checking): “Pete, you’re in the Anomaly right now, and that’s the reason you’re getting the flare indication. So, we do not want you to press with a flare jop.”

Paul: “Hey, Houston, I think you guys have got to put those . . . anomaly passes, all of them, on our pads. If that ever happens out of station contact, we’re going to come over the hill minus about 300 frames of film.”

Finally, on Day 22, they got lucky. At eight minutes after nine, Houston advised the crew that a “subnormal flare” had started in Active Region 31. Paul was on the atm console. Thirteen minutes later, Kerwin called back:

Joe: “Houston, Skylab. I’d like you to be the first to know that the plt is the proud father of a genuine flare. . . . Just about the time you called, he got a high count. And this time it was confirmed by image intensity count over 300, by a bright spot in the x-ray image, and a very bright spot on the xuv monitor. He found the flare in Active Region 31, a factor of ten brighter than anything we’ve seen. In other words, it was unmistakable once it happened.”

Paul got about two minutes of flare rise, surrounded by his crewmates, who had dropped everything when he called. Subsequent crews did much better; but they had the first one, and were “proud as new daddies,” as Paul put it.

Pete and Paul, the operators of the Earth Resources Experiment Package, became increasingly skilled at finding and photographing Earth “targets,” even through pretty extensive cloud cover.

Paul: “For information, it’s hard looking out at 45 degrees forward. You look through a lot of atmosphere. It’s hard to see detail. . . . and I got Fort Cobb, and the reservoir. . . . Okay, for special 01, all you’re getting is clouds so far. . . very low sun angle clouds; It’s like a scene from a biblical movie just before the heavens open up.”

Joe: “It’s going to break up in a minute over Lake Michigan.”

Besides doing the scientific erep passes, all the crewmen loved taking pictures of the world. They got pretty good at recognizing continents and islands—not perfect, but pretty good.

Houston: “Skylab, Houston with you for six minutes through Honeysuckle.”

Pete: “We’re just coming up on New Zealand. I think I’ll get some pretty good pictures this pass.”

Houston: “You’re sure that’s not Puerto Rico?”

Pete: “You said Honeysuckle before I said New Zealand.”

Houston: “Okay.”

Honeysuckle Creek was the tracking station in the beautiful hills south of Canberra, Australia, occupied by a few kangaroos. It’s closed now and very peaceful. Pete knew he was nowhere near Puerto Rico.

Each man had his favorites. Pete loved to photograph Pacific atolls; Paul favored the Great Lakes, the Rockies, and Australia and New Zealand; and Joe specialized in the Rockies and Chicago, his hometown; he kept looking for Wrigley Field and the Brach candy factory, where his dad had worked. After the spacewalk on Mission Day 26, they asked permission to use one extra roll of film just for Earth snapshots. Houston approved.

Back on Day 16, the crew had heard that President Nixon had scheduled a Summit Conference with General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev of the Soviet Union at the “Western White House” in San Clemente, California, for 18—26 June. On Day 24 it got a little more personal. Pete received a call from Nixon inviting them to attend. They accepted, and the president wished them all a happy Father’s Day.

On Day 25 Pete relayed Skylab’s respects to the Russian cosmonauts; this crew had now broken their duration record of nearly twenty-four days, set on the ill-fated Soyuz 11 flight. (The Soyuz 11 crew had been lost due to a loss of spacecraft pressure during its return from Salyut 1 in June 1971.) The following day there was a reply from Vladimir Shatalov, “Congratulations and a safe return.” The crew noted with satisfaction the last erep pass, the last run of each medical experiment. There was one more major chore to do: a spacewalk to retrieve that precious Apollo Telescope Mount film.

Around this time, Kerwin had written a poem to his wife that tried to capture the sensations of living in space:

I’m getting used to knowing how to fly.

When I was young I used to fly in dream Up ways so high and easy it would seem As if Earth wheeled and slanted, and not I.

And now it’s real. We move that way at will,

Like dust motes in a sunbeam. Push away,

Drift down your own trajectory, tumble, play And who can say what moves and what is still?

In this high sunlit ship the laws of space,

Height without vertigo, mass without weight,

Entrain our nerveways to their easy pace As if this rhythm were our native state.

What if Man were an exile from the sky?

Are we, perhaps, remembering how to fly?

Mission Day 26 was another eva day, and the crew was up at 2:00 a. m. Houston time. Pete’s jobs today would include brushing away a tiny piece of debris from the rim of the solar coronagraph (it was blurring the view) and attempting to free a stuck relay in one of the battery charger relay modules by hitting the airlock skin over it with a hammer (it was preventing the battery from charging). At 5:45 Pete took stock:

Pete: “All, right now, let me just stop one second. I got the brush, I got the hammer, I got two film trees and I got an ev-i and an ev-2 [him and Paul] in the Airlock. Is that right?”

Brushing off the debris proved easy. Tapping the relay was a bit more complicated. Pete had Rusty Schweickart, who was acting as Capcom, describe twice exactly where to hit. Joe, inside, made sure the charger was turned off. Then Pete gave the relay housing several mighty bangs.

Paul: “There it goes. Yes. Boy, is he hitting it! Holy cats!”

Joe: “Houston, EV-3. He hit it with the hammer. I turned the charger on, and I’m getting a lot of amps on the battery. Do you want to have a look?

Houston: “Okay. It worked. Thank you very much, gentlemen, you’ve done it again.”

Pete and Paul scrambled back into the airlock after just one hour and thirty-six minutes, with all the film. The crew pointed out that they had done their thing with a hammer and a feather, sort of like Galileo (or the Apollo 15 crew on the moon). And that evening, Pete read the following message from nasa: “To Captain Charles Conrad, Jr. On or about 22 June 1973, you and your crew will detach from Skylab One, leaving it in all respects ready

for the arrival of the Skylab 3 crew on or about 27 July, 1973. You will then proceed by space and air to the USS Ticonderoga without delay, and report immediately to the Senior Officer Present Afloat for duty.”

The next day was Day 27, Wednesday, 20 June. Skylab was cautioned that morning not to record anything requiring immediate attention on в Channel — they’d be home before it could be retrieved and acted on. The very last medical experiment was run—a final exercise tolerance test with Paul as the subject. Then there was a press conference.

The conference was relaxed and upbeat.

Joe gave his preliminary appraisal of the medical effects of a month in space: “Right now the score is ‘Man, three; space, nothing.’ . . . What’s been such a pleasant surprise is how nice we feel. We’re able to get up in the morning, eat breakfast and do a day’s work. I’m tremendously encouraged about the future of long-duration flights for that reason.”

Pete’s appraisal of the most significant accomplishment was “that we have now a ninety percent up-and-operating space station to turn over to the SL-3 crew.” He went along with Joe on the crew’s condition. Neither Pete nor Paul thought they’d eat as much as they did. And Pete thought he was in better shape than at the end of his eight-day Gemini 5 flight.

Paul emphasized how important it had been to have very high fidelity trainers and simulators on the ground. “And the things that are easy to do in the trainer are easy to here, ninety-eight percent of the time. And vice versa.” Their advice to the next crew: “Don’t forget the learning curve, don’t worry about your training, have fun.”

With that over, they started packing and got so far ahead of the flight plan that they decided to go to bed another hour early. Tomorrow was going to be deactivation day.

First call on Day 28 was at 1:00 a. m., and for the first time, Houston woke the crew with music: “That’s ‘The Lonely Bull’ for you, Pete.” Pete said, “You should have started doing that on Day Two,” and a tradition was born. Ever since Mission Control has specialized in playing wake-up music for Shuttle and International Space Station (iss) crews, tailored to their personalities.

They raced around the workshop. In fact, Paul clocked one complete traverse from the Command Module to the Trash Airlock at “sixty seconds loaded with gear, twenty seconds at max speed” — just to help out the activity planners. They took front and side “mug shots” of one another for the doctors. Joe squeaked his rubber ducky, the one his brother Paul, the Marine pilot, had carried on missions over Viet Nam. Pete said, “It’s like a day-before-Christmas party up here, Hank.”

Houston (Hank Hartsfield, the Capcom): “You know, it’s 5 in the morning down here.”

Paul: “How about giving him something to do, Houston, will you please?”

Houston: “Can you stomp your foot up there in zero-G as easy as you can in one G?”

Pete: “You bet your sweet bippy, you can also go ‘Ah—haaa!’”

Paul: “You can only stomp once.”

So everything was sailing along. Then it happened. The Trash Airlock jammed.

Pete (ten minutes before eight): “Okay, Houston. We’ve got some bad news for you. We were jettisoning the charcoal canister through the trash airlock per procedures, and it has hung itself in the airlock. . . . We’re working the problem, but—it’ll be pure luck if we bounce it off that lip and get it out of there.”

Pete, Paul, and Houston began to work the problem in an atmosphere of grim hurry. No place to dump trash would give the next crew a terrible problem. Story Musgrave, Joe’s backup, went over to the mockup to try to reproduce the problem and solve it. Finally, at 9:15, Paul reported: “So having wound up there [at the end of a malfunction procedure that didn’t work] we started working on it a little more. And by judicious application of muscle, we did manage to get it up and free. So the trash airlock is operative once more.” In other words, they kept fooling with it till something worked—just like you fix things at home. Everybody sighed with relief and pledged never again to put something that big down without taping up all the edges. And they carried on. There would be only one more glitch before the mission ended.

To bed at 2:00 p. m. Houston time, the crew played “America” to the satisfaction of Mission Control. Up at 7:00 p. m., sleepy and in for a long day. They’d be tired and ready for bed about the time they hit the water. Joe told Karl Henize, the Capcom, “It’s wonderful of you to pretend it’s morning, just for us.” Lots of last-minute questions, cross checking that they had the right procedures, messages, and times. There was another review on exactly how to mate the docking probe and drogue, which had nearly sabotaged the mission on Day i, and how to proceed if they didn’t mate. (They did.)

The last problem was that Skylab’s refrigeration system now began warming up. Houston worked the problem for nearly four hours while the crew finished stowage and donned suits. Would their undocking be delayed, canceled? Finally Houston decided the system’s radiator, positioned right aft at the end of the workshop, where the engine nozzle would have been, had frozen up. They maneuvered the cluster to point it at the sun. The crew closed the tunnel hatch and waited in their couches for a go to undock. At 3:30 a. m. it was delayed. At 3:54 it was given; the radiator was unblocked and the loop was cooling down.

Pete flew around Skylab for a farewell inspection and photos; it looked small and friendly as they backed away, with its lopsided solar panel and crumpled parasol against a cloud-flecked ocean background.

The first of two deorbit burns came at a little after five, followed by the last star sightings through the Command Module’s telescope. Joe got drinks for everyone before strapping in for the final burn and decided to save his until after splashdown. At 7:30 Houston gave Skylab the weather in the recovery area.

Houston: “There’ll be two recovery helos, with the call signs Recovery and Swim. And you’re being awaited by the U. S.S. Ticonderoga. And we’re waiting to see you back here in Houston, too.”

Pete: “Alrighty. You can relay to the Tico, ‘We’ve got your Fox Corpen and our hook is down.’” [Pete was playing the Naval aviator coming in for a landing on the carrier’s deck. Fox Corpen is the ship’s heading. It sounded great to the rest of his crew.]

The final deorbit burn was successful at twenty-one minutes after six (Pacific Time). Joe and Paul were surprised to note that they “grayed out” a little during the burn. Pilots knew that fighter plane maneuvers that produced high levels of acceleration—loops or very tight turns—could drain the brain of blood and produce a reduction (grayout) or complete loss (blackout) of vision, or even loss of consciousness. The Service Module engine only produced about one G worth of thrust. That was normally a trivial acceleration. But nobody’d been weightless for a month before.

Joe: “I went kind of gray and then I was coming back.”

Paul: “I think what gets you on that is the spike [abrupt] onset.”

Joe: “We’ll see; there’s no spike onset to entry.”

Entry G force would build up to about four and one-half Gs but very gradually. No problem was really anticipated; but they did rehearse what switches had to be thrown to assure successful splashdown, and by whom.

Joe: “Remember, els Logic to auto if you’re blacking out.”

Pete: “Right.”

Nobody blacked out. Pete got the Earth Landing System switch to auto right on time. And at 6:45 Skylab contacted Recovery, at 4,500 feet, with three good main chutes.

The uss Ticonderoga, cv-14, was a proud old ship at the end of its thirty years of service. Recovering Skylab 1 would be its last cruise. Everyone knew that, and it gave the ship a sense of celebration, regret, and tension.