The Group 5 Rookies

Of all of the groups of astronauts, the fifth—jokingly self-dubbed “The Original Nineteen” in a nod to the Mercury “Original Seven”—had the most diverse fates when it came to their eventual spaceflight assignments. Nine of them would make their first flights during the Apollo program (Charles Duke, Ronald Evans, Fred Haise, James Irwin, T. K. Mattingly, Edgar Mitchell, Stuart Roosa, John Swigert, and Alfred Worden), with three of them (Duke, Irwin, and Mitchell) walking on the moon. Four would make their rookie flights during the Skylab program (Jerry Carr, Jack Lousma, Bill Pogue, and Paul Weitz); one during the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (astp) (Vance Brand); and three would not fly into orbit until the Space Shuttle began operations (Joe Engle, Don Lind, and Bruce McCandless; Engle had flown to the edge of space on the experimental x-15 plane before joining the astronaut corps). One of the members, Ed Givens, died before flying a mission, and another, John Bull, developed a medical condition that disqualified him from flight status.

Group 5 member Paul Weitz, who made his first flight as part of the first Skylab crew, said that he does not remember any indication being made when his class joined the corps what their role would be, which he said he could live with: “I can’t speak for anyone else, but I just wanted to get an opportunity to fly in space.”

Even if no formal promise regarding their role had been made, some members of the group had some expectations. “When we were brought onboard, there was no end at Apollo 20,” Jack Lousma said. “We were going to land on the moon before the end of the decade, and we’re going to explore the moon. And there was no end to the number of Saturn missions there was going to

|

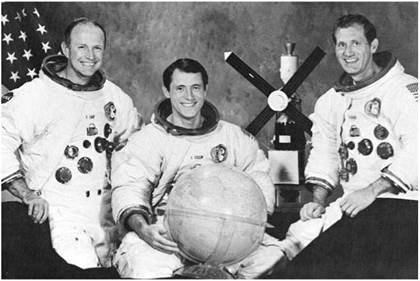

6. Members of the third Skylab crew: (from left) Jerry Carr, Ed Gibson, and Bill Pogue. |

be, the number of Saturn flights, Saturn vs, or the number of landings on the moon. It was going to start with the landing, and then it was going to be increased duration, staying on the moon up to a month. And they were going to orbit the moon for two months; I guess that was more of a reconnaissance type of thing.”

The members of the Original Nineteen were competing for missions both with one other and with their predecessors still in the corps, a competition made even tighter by the cancellation of Apollo missions 18 though 20. “I was very much disappointed that the last three missions to the moon were canceled—I thought I had a chance of making one of those missions,” Weitz said.

While there may not have been much overt competition among the Group 5 astronauts for the remaining Apollo berths, Weitz said, “It became obvious that some of the folks were doing their best to position themselves to punch the right cards to be considered for early flights. But everyone wanted to fly as soon as possible, and I think that no one was consciously considering giving up on Apollo-era flights so that they might get an early Shuttle flight.”

Though he had been disappointed with the cancellation of the last three Apollo missions, Weitz said that he was pleased with his eventual rookie assignment. “I really enjoyed flying Skylab with Pete and Joe, and I thought we did our part to further the benefits of human space research.”

Jack Lousma said, “I was a little naive. I wasn’t a politician; I’d never been in a political organization. I just figured, the harder I work, the better I do. That wasn’t good for this particular system, but I wasn’t smart enough to know that. Moreover, I didn’t know anybody when I came. A lot of the other guys had worked with each other on different projects in the Air Force and things, and I was just kind of a lone ranger. And I was the youngest guy selected, most junior, least experienced. So it seemed as though the people that had more experience, were a little bit older, or had done different things than I had were selected before me. Like Fred Haise was selected for the Lunar Module. Ed Mitchell worked on that. They were senior guys. And Fred was such a competent guy in aviation. So I was just going to do my best and work as hard as I could and see what happened, and if it came to a point where I had to be more overt about this, I would have felt that I’d earned the right to speak up.

“There was some amount of politics to the system of selection, but for the most part I felt that Deke Slayton was a fair guy, and I thought he selected the right people for the right job. I felt that everybody there was qualified to handle any mission that would come their way, but I felt that the selections as Deke made them were fair. He would come in and assign maybe two crews for a couple of Apollo flights, assign a backup crew, make a few guys happy and a lot of guys mad. But he would always say, ‘And if you don’t like that, I’ll be glad to change places with you.’ And nobody could refute that. ’Cause poor old Deke, he still hadn’t flown at all.”

Lousma was one of the members of Group 5 who reached a point where he was confident the moon was within his grasp, only to have it snatched away. Upon joining the corps he had originally been put on a different track as one of the first members of his class to be assigned to Apollo Applications rather than to Apollo. Even before he had completed his initial astronaut training, Lousma was tapped to work on an instrument for one of the lunar-orbit aap flights that was planned at the time. Lousma had come to the astronaut corps from a background in military reconnaissance, and so was a perfect fit for the project, which involved using a classified Air Force high-resolution reconnaissance camera attached to an orbiting Apollo capsule to study the surface of the moon.

After Lousma had spent a year working on that project, however, the planned mission was canceled, and he was back to square one. It seemed, though, that fortune was smiling on him. Fred Haise, who had been the corps’ lead for Lunar Module testing and checkout, had been assigned to the backup crew for Apollo 11, which meant he would then be rotating up to prime a few flights later. (Under the standard rotation, Haise would have been Lunar Module pilot for Apollo 14, but Alan Shepard’s return to active flight status bumped the original 14 crew up to Apollo 13.) The corps needed someone to take the Lunar Module assignment that Haise had vacated, and at the same time Lousma needed a new ground assignment. The fit was perfect.

While serving as Lunar Module support crew for Apollo 9 and 10, Lous – ma was also scrounging time in the lander simulator whenever he could. “By the time all of that was said and done, I had seven hundred hours in the Lunar Module simulator, plus all the knowledge that went with the systems of how the lunar module worked,” Lousma said. “Al Bean, when he flew, wanted the Lunar Module malfunction procedures revised, so I did that for him. I knew how this thing worked. So I figured I was probably destined for a Lunar Module mission.

“Before they canceled the last three missions, as I recall there was a cadre of fifteen guys that all worked together to somehow populate the last three missions; and some of them were guys that had flown already, and some of them weren’t. Once it got to this cadre of fifteen guys, I don’t remember there being any politics there. I wasn’t involved if there was. I was just really focused on doing the best I could and qualifying on my own. I felt I was ready to do it. I was not a political person. I don’t think Deke was much of a political person at all. He was somewhat predictable in that the guys who had been there the longest were going to fly first. And in that group of people, probably the guys that were going to fly first were a little bit more senior, militarily speaking, and I was a junior guy; I was twenty-nine years old.

“That’s the way Deke worked. I think Jerry Carr would have flown to the moon before me. Jerry was senior to me in the Marines, so I’m not going to fly before him. The way it worked out on Skylab was I ended up flying before Jerry. And to offset that, Deke assigned Jerry to be the commander, not just the ride-along guy on the third Skylab mission. That’s the way his mind worked. So to some extent, he was kind of predictable for people who were coming up through the ranks. He was kind of unpredictable for guys who had already flown. So there was probably more politics between those guys than there was between me and my friends. Deke never wanted much politics, I don’t think.

“I don’t know if I’d have been going to the moon or not, but there were three flights there for which I was eligible, and I was a Lunar Module-trained guy, so I thought I was definitely going on one of them.”

But, of course, it was not to be. The final three planned Apollo missions were canceled and with them went the hopes of Lousma and the others that they might reach the moon. With those missions canceled, Skylab became the next possible ticket to space for the unflown members of Group 5 (and their Group 4 predecessors). But even after the nine Skylab astronauts were told they had been assigned to the flights, some still had a sense of uncertainty, particularly in the wake of the cancellation of the last three Apollo flights.

“The Skylab missions were always threatened to not fly for a long long time,” Lousma said. “It was never sure until the last six months or a year that the Skylab was going to get to fly. There were those that said, ‘Let’s save the money and put it in the Shuttle.’ So I always felt like I could lose that Sky – lab mission, even when I was training for it.

“Somehow I found out that there was probably going to be a flight with the Russians and probably Tom Stafford was going to command that. Maybe it was common knowledge, maybe it wasn’t. But I decided that if Sky – lab doesn’t fly, I’m going to be ready for the next thing. So I went while I was training for Skylab and took a one-semester course in the Russian language, took the exams and documented it and all that sort of thing, turned it in with my records, and said, ‘Here you go, Deke, in case you’re looking for a guy to go on the Russian flight, well, I’ve got a little head start on the language thing.’ It turns out that before we went on the Skylab mission I knew I was going to be on the backup crew for the Russian flight. It didn’t matter then, because Skylab was going, so backup was okay. But I remember being concerned about Skylab not flying.”

Lousma said he is frequently asked if he felt that Skylab was a poor consolation prize for the lunar flight he missed out on. “ ‘Going on a space station mission instead of going to the moon, did you feel bad about it?’ Heck no, I didn’t,” he said. “I thought any ride was a good ride. And I felt that there weren’t that many rides to go around, so this was going to be all right. But moreover, we were doing things that hadn’t been done before. This is what I

think the lure was for most of our guys, to do things that hadn’t been done. All the things that Apollo did, we became operationally competent in.

“We knew we could fly in space. The question was, could we survive in space for long periods of time in weightlessness, and moreover could we do useful work. [Skylab] proved that this could be done, and it also demonstrated that evas in zero-gravity were doable if you were properly trained and had the right equipment and had been properly prepared. And we didn’t really know that either.”

The term “zero-G” is frequently used to indicate when things appear to be “weightless.” When flying in space, crewmembers do feel weightless, and they really are, but not because there isn’t any gravity at their altitude, about 435 km (270 miles) above the Earth for Skylab. In fact, the force of Earth’s gravity is about 87 percent as strong there as it is on the ground. The essential difference is that on Skylab the crews were in what physicists call “free-fall,” meaning that there was nothing to support their weight, like the ground or a chair. Instead, they were falling freely toward the center of the Earth, our “center of gravity,” just like a diver or a gymnast does until they hit water or the ground. So to be more precise, the free-fall toward the Earth’s center is the source of the apparent weightlessness in space. Space flyers do not hit the Earth because they are traveling so fast that their orbit just matches the curvature of the Earth and the Earth’s surface drops away from beneath them just as quickly as they fall toward it. When “zero-g” is used to mean weightlessness, this is what the correct explanation should be.

While in-space evas had been carried out successfully in the final Gemini flights and then in Apollo, Lousma noted that they were nothing like the spacewalks performed during Skylab. The Skylab spacewalks were much longer and, unlike the earlier carefully planned and prepared spacewalks, involved responding to situations as they occurred.

“We were the first real test of whether you could have a useful space laboratory, and you could do scientific experiments of all sorts that we never did in Apollo, and get useful data back, and investigate things that had not been investigated before,” Lousma said. “I didn’t get to go to the moon, but I got to do something which was one-of-a-kind, first of a kind, to demonstrate all of those things that we were wanting to know and had to learn to go to the next step, and that’s the one that we’re going to take in the next couple of decades. From that point of view, I think Skylab is NASA’s best –

kept secret. We learned so many things that we didn’t know, and we did so many things for the first time.”

Like most of the members of the early groups of astronauts, Jerry Carr’s path to becoming an astronaut began with a love of aeronautics developed in his youth. For Carr, who was born in 1932 and raised in Santa Ana, California, that interest was first spurred during World War 11, when he would spot airplanes, including experimental aircraft flying overhead through the southern California sky. He and a friend would ride bicycles fourteen miles to the airport on Saturdays, where they would spend the entire morning washing airplanes. In compensation for his efforts, he would be paid with a twenty – minute flight. During his senior year in high school, he became involved in the Naval Reserve. He was assigned to a fighter jet and was given the responsibility of keeping it clean and checking the fuel and fluid levels.

After high school Carr attended the University of Southern California through the Naval rotc and earned a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering in 1954. Following his graduation, Carr became a Marine aviator. After five years of service, he was selected for the Naval Postgraduate School, where he earned a second bachelor’s degree in aeronautical engineering in 1961. Carr was then sent to Princeton University and earned a master’s degree in the same field a year later.

Three years later, he saw the announcement that NASA was seeking candidates for its fifth group of astronauts. He made the decision to apply on a whim. He was friends with C. C. Williams, who had been selected in the third group of astronauts in 1963. Carr figured if Williams could make it, he was curious to see how far through the process he could go. On April Fool’s Day in 1966, Carr learned just how far he had gone when he received a call from Capt. Alan Shepard informing him that he had been selected to the astronaut corps.

Jack Lousma wasn’t always going to be a pilot. Sure, Lousma, who was born in 1936 in Grand Rapids, Michigan, loved airplanes as a kid, building models and going out to watch them land and take off. And he had two cousins who were pilots and still remembers the time one of them flew a jet over his farm so low “I could almost see his eyeballs,” as he recalled in a NASA oral history interview. But Lousma wasn’t always going to be a pilot. Through high school and into college, he planned to be a businessman. However, during his sophomore year, he says, he decided he just couldn’t figure the business classes out and decided to get into engineering. And as long as he was going into engineering, he did love airplanes, and the University of Michigan did have a great aeronautical engineering program.

While completing his bachelor’s degree in aeronautical engineering, though, he saw a lot of movie footage of fast-flying jet airplanes. And so he decided the best thing for an engineer who planned to design planes to do would be to learn to fly them. After being turned down by the Air Force and Navy because he was married, he found out that the Marines not only had airplanes, they had a program that would take married people. After completing his training and deciding he wanted to make a career of the Marines, he went on to attend the Naval Postgraduate School, earning a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering.

Lousma had reached the point where he was starting to look for new challenges when he heard that NASA was selecting its fifth group of astronauts, and he decided that fit the bill perfectly. His application process was nearly cut short, however, by a requirement that candidates not be over six feet tall. According to his last flight physical, Lousma was 6 feet i. The Marines Corps, which screened his astronaut application, agreed to give him a “special measurement” by his flight surgeon. This one came out to 5 feet, 11 7/8 inches. “I was really 5 foot, 13 inches, but I didn’t tell anybody,” he joked.

Garriott notes that at the time of their Skylab flight, Lousma had only had nine birthdays, having been born on 29 February. “But ‘the Marine’ acts in a much more mature manner, and if there ever was a true ‘All American Boy’ in a quite positive sense, this is your man,” he said.

Bill Pogue also was fascinated by airplanes in his youth but like Lousma had plans for his life that did not include being a pilot. Fate, however, had other plans, and Pogue ended up thrust into following his childhood fascination. Born in 1930 in Okemah, Oklahoma, Pogue planned during high school and college to be a high-school math or physics teacher, following in his father’s schoolteacher footsteps. Pogue earned a bachelor’s degree in education at Oklahoma Baptist University. After the Korean War broke out, though, Pogue decided it looked like he was going to be drafted and enlisted in the Air Force. He was sent to flight-training school and then to Korea, where he was a fighter bomber pilot. In the six weeks before the armistice, he flew a total of forty-three missions, bombing trains and providing air support for troops.

An assignment to leave Korea to serve as a gunnery instructor at Luke Air Force Base in Phoenix, Arizona, proved to be fortuitous when after two years there he was asked to join a recently formed group based at Luke—the Thunderbirds air demonstration unit.

When he left the Thunderbirds, Pogue was given his choice of assignment, and he asked to be allowed to earn his master’s degree. He was reassigned to Oklahoma State University, where he earned his master’s in mathematics. About halfway through a five-year tour of duty as a math instructor at the Air Force Academy, he successfully petitioned to be allowed to work toward a goal of becoming an astronaut. He attended the Empire Test Pilot School in England. After completing that, he spent a couple more years there and then transferred to Edwards Air Force Base. Before he even moved there, however, he learned that NASA was selecting a new group of astronauts, and from his first day at Edwards, he was already working to leave Edwards to join NASA.

Unlike Lousma and Pogue, Paul Weitz did always want to be a pilot. Specifically, Weitz, born in 1932 in Erie, Pennsylvania, wanted to be a pilot for the Navy. His father was a chief petty officer in the Navy and during World War II was in the Battle of Midway and the Battle of Coral Sea. That made a deep impression on Weitz, and by the time he was around eleven, he had decided he was going to be a naval aviator.

Toward that end he attended Penn State on a Navy rotc scholarship, completing his time there with a bachelor’s degree in aeronautical engineering and a commission as an ensign. An instructor there advised Weitz that if he wanted to make the Navy a career, he should begin by going to sea, so he spent a year and a half on a destroyer before going to flight training. From there he spent four years with a squadron in Jacksonville, Florida, where he met Alan Bean.

The next few years of Weitz’s life were not necessarily as he would have planned them. After initially being turned down for test-pilot school, he was accepted for the next class but not until he had already been ordered across the country for an air development squadron. Since the Navy had just moved him from one coast to the other, they refused to move him back for test-pilot school. At last after two years he received unsolicited orders to attend the Naval Postgraduate School, where he was in the same group as Jack Lous – ma and Ron Evans, who went on to be the Command Module pilot for the Apollo 17 mission. Further complicating the situation, Weitz found himself allowed only two years at a school where a master’s degree was a three – year program. With the aid of sympathetic professors, he was able to earn his master’s in aeronautical engineering in the two years he had.

The next year, he made a combat tour in Vietnam. While in the western Pacific, he got a message from the Bureau of Naval Personnel asking if he would like to apply to be an astronaut. Though Weitz had never given the matter any thought before, he decided that he would, indeed, like to be an astronaut.

Those nine men would make up the crews of the three Skylab missions. Pete Conrad and Al Bean, the two veteran astronauts, became the commanders of the first two Skylab crews. Conrad was joined by pilot Paul Weitz and science pilot Joe Kerwin. Bean’s crew consisted of himself, pilot Jack Lous – ma, and science pilot Owen Garriott. Rookie Jerry Carr was assigned as the commander for the third crew, joined by pilot Bill Pogue and science pilot Ed Gibson.

One veteran and five rookies made up the backup crews for the three Skylab missions. Rusty Schweickart, the Lunar Module pilot for the Earth – orbit Apollo 9 mission, was the commander of the backup crew for the first mission, joined by pilot Bruce McCandless and science pilot Story Mus – grave. Commander Vance Brand, pilot Don Lind and science pilot Bill Lenoir (Lenoir and Musgrave were members of the second group of scientist astronauts NASA selected) served as the backup crew for both the second and third Skylab missions.

The first crew chose for their mission patch an image depicting the Earth eclipsing the sun, with a “top-down” view of a silhouetted Skylab in the foreground. The patch was designed by science-fiction artist Kelly Freas.

The second crew’s patch, with a red, white, and blue color scheme, featured Leonardo da Vinci’s famous Vitruvian Man drawing of the human form in front of a circle, half of which showed the western hemisphere of the Earth, and the other half depicted the sun, complete with solar flares. The patch reflected the three main goals of their mission—biomedical research, Earth observation, and solar astronomy.

|

7- (Clockwisefrom top left) The Skylab i mission patch, the Skylab 11 patch, the Skylab 11 “wives’ patch,” and the Skylab ill patch. |

The third crew’s patch featured a prominent digit “3” with a rainbow semicircle joining it to enclose three round areas. In those three areas were depictions of a human silhouette, a tree, and a hydrogen atom. The imagery on the patch symbolized man’s role in the balance of technology and nature.

There was one other Skylab “mission patch,” a companion to the second crew’s patch. The wives of the three Skylab 11 astronauts had been involved in the creation of that mission’s patch, and decided they wanted to do something a little extra. Working with local artist Ardis Settle, who had contributed to the official patch, and French space correspondent Jacques Tiziou, they created their own Skylab 11 “wives’ patch.” The central male nude figure drawn by Leonardo had been replaced with a similar but much more attractive female nude and the crew names altered to Sue, Helen Mary, and Gratia.

“One of our first tasks when reaching orbit was to unpack our ‘flight data file,’ carried up in our csm [Command Service Module],” Garriott said. “What we did not expect to see when we unpacked our individual ‘small change sheets’ and ‘check lists’ was a new crew patch with a much more memorable female nude in the center!”