The Homesteaders

The nine astronauts selected to serve on the Skylab flight crews represented three different demographics. Only two, Alan Bean and Pete Conrad, had flown in space before. Three of them, Owen Garriott, Ed Gibson, and Joe Kerwin, were members of the first group of scientist astronauts NASA had selected. The remaining four, Jerry Carr, Jack Lousma, Bill Pogue, and Paul Weitz, were unflown pilot astronauts.

The Moonwalkers

Not only were Bean and Conrad the only two flown astronauts on the Sky – lab flight crews, they had flown their last mission together; on it, the two had walked on the moon.

With three previous spaceflights under his belt, Pete Conrad was far and away the senior member of the three Skylab crews. Born in June 1930 in Philadelphia, Conrad at an early age developed a love of flying. After earning a bachelor’s degree in aeronautical engineering from Princeton, Conrad pursued that love as a naval aviator. He went on to earn a place at “Pax River,” the Navy Test Pilot School at Patuxent River, Maryland, where he served as a test pilot, flight instructor, and performance engineer.

It was there that Conrad first applied to become an astronaut in the initial selection process that brought in the original Mercury Seven. Though he was not selected in that round, the experiences of friends who were chosen inspired him to try again, and in 1962 Conrad was named as part of NASA’s second class of astronauts, a group of nine men that also included Neil Armstrong, Frank Borman, Jim McDivitt, Jim Lovell, Elliot See, Tom Stafford, Ed White, and John Young.

His first spaceflight came three years later when he served as pilot of the third manned Gemini mission in August 1965, commanded by Mercury astronaut Gordon Cooper. Gemini 5 was to have a mission length of eight days, the first of two times in his life that Conrad would set a new spaceflight duration record.

|

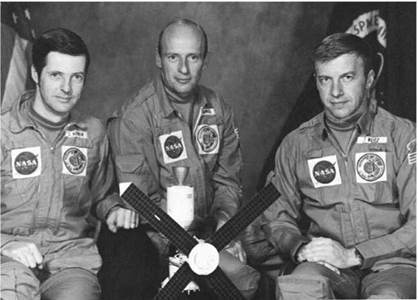

4- Members of the first Skylab crew: (from left) Joe Kerwin, Pete Conrad, and Paul Weitz. |

Just over a year later, Conrad moved up to a command of his own, flying the Gemini ii mission with pilot Dick Gordon in September 1966. The sec – ond-to-last Gemini mission, flown just months before manned Apollo flights were then scheduled to begin, Gemini 11 was intended to gain more experience with rendezvous and extravehicular activity (eva), two areas which would be vital for Apollo.

When Conrad flew again three years later, the success of Apollo was a fait accompli. Four months earlier nasa had fulfilled Kennedy’s mandate “of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth” before the decade was out. Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin had become the first and second men on the moon on 20 July 1969, and next it was Conrad’s turn. The Apollo 12 mission reunited Commander Conrad with Command Module pilot Gordon, and Bean joined the two as Lunar Module pilot. On 19 November Conrad and Bean left Gordon in lunar orbit and touched down on the surface. As he became the third man to walk on the moon, Conrad referenced Armstrong’s famous “That’s one small step for man; one giant leap for mankind” line in his own first words on another world: “Whoopee! Man, that may have been a small one for Neil, but that’s a long one for me.”

Alan Bean was born in 1932 in Wheeler, Texas. Like Conrad, Bean earned

his bachelor’s degree (in aeronautical engineering at the University of Texas) and followed that with service in the Navy, having been in Reserve Officer Training Corps (rotc) while in college. After a four-year tour of duty, Bean also attended Navy Test Pilot School and then flew as a test pilot of naval aircraft.

He was selected as an astronaut in NASA’s third group in October 1962—a class almost as large as both of its predecessors combined—along with Buzz Aldrin, Bill Anders, Charles Bassett, Gene Cernan, Roger Chaffee, Michael Collins, Walt Cunningham, Donn Eisele, Ted Freeman, Dick Gordon, Rusty Schweickart, David Scott, and C. C. Williams.

Bean’s first crew assignment was as backup for Gemini 10, along with C. C. Williams. While his crewmate preceded him in getting an Apollo assignment, as backup for Apollo 9, that slot went to Bean after Williams’s death in a crash of one of the T-38 jets used by the astronaut corps. From that assignment, Bean rotated up to the prime crew (the flight crew, as opposed to the backup crew) of Apollo 12.

It was his participation in the Apollo 12 mission with Pete Conrad that led to their joint involvement in Skylab. Bean had previously worked on Apollo Applications, supporting the program as a ground assignment while waiting to be placed on a crew. He served as the astronaut head of aap until he became a member of Conrad’s backup crew for Apollo 9. After transferring from aap to Apollo, Bean maintained his interest in the program and kept up with its development (noting with approval, for example, the change from the wet workshop to the dry).

Alan Bean recalled the decision to pursue a Skylab mission: “We were starting to talk about what we wanted to do; this was on the flight home from the moon. Dick wanted to stay in Apollo because we knew we were cycling threes, so he could be commander of Apollo 18. [Under the regular rotation, an astronaut, after a mission, would skip two missions, be on the backup crew for the third, skip two more, and then be on the “prime” crew for the next mission.] First, we decided we’d divvy up every flight, and we’d swap around. This was Pete: Dick would be the commander of the next one, and the three of us would run the space program. But then as we got to talking about it, Pete wanted to do Skylab. And we both felt that we didn’t want it to get crowded, other people deserved chances too. So we thought, well, we’ll try to be part of Skylab.

“So Pete says, ‘That looks like it’d be a good thing to do, looks like it’d be fun.’ I don’t think Dick was interested. A lot of the astronauts weren’t interested in flying for twenty-eight days or fifty-six days. We were; we thought it’d be good adventure.

“I never did go and see Deke. I should have done it, but I never did it. But Pete went over and talked with him. It seems to me the announcement in the meeting of me and Owen and Jack [as a crew for Skylab] was a surprise to me, or maybe Deke phoned me and said this is what is going to be announced. But he didn’t consult me about Owen and Jack. It turned out great. We ended up with the best crew, no doubt about it.”

After Apollo 12 the three members of its crew were sent by nasa on a goodwill tour of the world, and upon returning Bean and Conrad transferred from Apollo to Skylab. In addition to their common background as moonwalking spaceflight veterans, the first two Skylab commanders shared another trait as well. Each has been described by members of their Skylab crew as being one of the most motivated men in the astronaut corps. In Conrad’s case a lifelong drive to succeed had been increased by his rejection from the Mercury astronaut selection. “Pete was rejected, and the basis for his rejection was a psychiatric evaluation that he was psychologically unsuited for long-duration space missions,” Kerwin recalled in an oral history interview for Johnson Space Center in 2000. “So here’s Conrad; he’s gone to the moon, he’s up here in Skylab with us on the first-ever long-duration space station mission, and he’s saying, ‘I’ll show that son of a gun who’s psychologically unsuited for what!’

“So he was very motivated to do a great job on Skylab. Just the kind of commander you want. He exercised more than we did and kept us all up to a very high level, even coming home. He said, ‘Guys, we’re going to walk out of this spacecraft. There’s going to be none of this carrying us out on stretchers stuff. . . . When that hatch opens, I’m outta here, and I want you guys to follow me.’” Bean’s drive was an extremely important factor in the direction the second Skylab mission took. Owen Garriott said that a major reason for the incredibly high productivity of his crew was that “We had one guy that was better motivated than anybody in the astronaut office.”

Despite having accomplished things as a Navy test pilot and astronaut that many other people only aspire to, Bean continually pushed himself further. Even during his days in the astronaut corps, Bean was a devotee of motivational tapes. Three decades after the time of Skylab, Bean continues to listen to the tapes, still working to motivate himself to accomplish all he can, to be the best he can. When his spaceflight days were behind him, Bean channeled that drive into his devotion to capture in his paintings the emotional aspects of his unique experiences. “I’ve always had a point of view that you don’t have to be the smartest person, or the healthiest, or the brightest person to really do good work,” Bean said. “I’ve never felt like I was that, but I always felt like I could do good work. Like these paintings, I never was the best artist in class, but I can do better art than anybody that was ever in any of my classes because I just keep doing it.”

Dick Gordon, who flew with both men on the Apollo 12 mission, declined to speculate as to which was the more motivated, saying only that each was very motivated in his own way and that each had his own distinctive leadership style. He added, “If the space program doesn’t motivate you, you’re in the wrong place.”