A Black Knight Launcher?

There is a reference made in a file in the Public Record Office1 to a telephone conversation in which the RAE was asked by an official at the Ministry of Aviation in October 1961:

What has the RAE done on solid propulsion and what has been done on smaller rockets? (Opinion and any possible objections).

The context is not entirely clear, but Dr Schirrmacher of RAE sent a fairly lengthy reply, and part of this reads:

![]()

![]()

(b) For smaller satellites two solutions are worth mentioning:

(b) For smaller satellites two solutions are worth mentioning:

Black Knight boosted by two Ravens and carrying a Rook as 2nd stage with a Cuckoo as 3rd stage. One will get 100lb into a 200mile orbit. Present development at Westcott for an improvement of the mass fracture [sic – probably ‘fraction’] indicates that the payload could probably be increased by a factor 2 [sic].’

Dr Schirrmacher was referring to a report which was written at RAE in January “ 1961 as part of a more general paper on the

possibilities of using Black Knight as a satellite launcher, and the study was based around what might be called the ‘Dazzle’ Black Knight – i. e., the 36-inch vehicle with a lift-off thrust of 21,6001b.2

It is also interesting to note, in the Black Knight context, that Saunders Roe’s Aerodynamics Department and Computing Department had produced a joint report of a vehicle which they christened LOVER, standing for Low Orbit Vehicle for Experimental Research. This was

nothing more than the 54-inch Black Knight together with the Kestrel motor (but pointing upwards). Somewhat optimistically, it concludes that

The proposed satellite launcher using a 4′ 6" diameter Black Knight as a first stage and a “Kestrel” powered second stage can be used to inject a small satellite into orbit at an altitude of between 100 and 200 n. miles.. .3

The 54-inch Black Knight is a rather more plausible contender for a satellite launcher than original 36-inch version, and in the context of what might have been possible in 1963, some performance figures would be helpful:

|

Thrust |

Burn time Total impulse |

Weight |

Diameter |

||

|

(lb) |

(seconds) |

(lb. seconds) |

(lb) |

(inches) |

|

|

36-inch Black |

21,600 |

120 |

2,600,000 |

13,000 |

36 |

|

Knight 54-inch Black |

25,000 |

140 |

3,500,000 |

17,000 |

54 |

|

Knight Raven VI |

15,000 |

30 |

450,000 |

2,540 |

17 |

|

Rook IV |

66,700 |

6.65 |

480,000 |

2,370 |

17 |

|

Cuckoo II |

8,200 |

10 |

82,000 |

500 |

17 |

|

Kestrel |

27,000 |

10 |

276,000 |

1,600 |

24 |

|

Waxwing * in vacuum |

3,500* |

55 |

195,000 |

760 |

30 |

Why 1963? This was the time when the design which would become Black Arrow was evolving. Instead of Black Arrow, this section will consider the possibilities of a launcher using Black Knight as a central core and adding assorted solid motors, both as strap-on boosters and as upper stages.

Adding solid fuel boosters to Black Knight:

Initial Thrust Total impulse (lb) (lb. seconds)

36-inch Black Knight + 2 Ravens 36-inch Black Knight + 4 Ravens 54-inch Black Knight + 2 Ravens 54-inch Black Knight + 4 Ravens Black Arrow

36-inch Black Knight + 2 Ravens 36-inch Black Knight + 4 Ravens 54-inch Black Knight + 2 Ravens 54-inch Black Knight + 4 Ravens Black Arrow

The total impulse could be increased even further by ‘stretching’ the Black Knight stage – that is, increasing the size of the fuel tanks. The Raven is the most suitable, since it has a relatively long burn time, so that the central core has had time to burn off some of its fuel. Total impulse is, of course, not the only criterion by which a rocket motor should be judged, but it is useful in this context as a rough and ready guide.

There would be very little extra development work needed to be done, since by 1961, the Raven, Rook and Cuckoo were fully developed – the Raven and Cuckoo were in use on the Skylark rocket, and the Cuckoo II was also the second stage for the 36-inch Black Knight. The Kestrel was to have been the second stage for the 54-inch Black Knight, and so if we have the 54-inch Black Knight, we also have the Kestrel. Waxwing is the only rocket not available in 1963, since it was developed specifically as the apogee stage for Black Arrow.

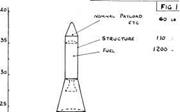

In a launcher which has several stages, it helps if they are well matched in weight. For reasonable performance, very roughly the first stage might be around 60% of the all up weight, the second stage perhaps 30%, and the third stage 10% or so. They also need to be matched in thrust: if the first stage only has a limited thrust, it cannot lift the upper stages. One of the points of the strap-on boosters is to give that extra thrust, so that when they have burnt out, the main stage has used up enough fuel to carry on by itself.

Another consideration is geometry, and this is where the idea of using the Rook and Cuckoo as second and third stages falls down. The Rook had a diameter of only 17 inches (at this time, 17 inches was the largest solid motor made in the UK). The Kestrel would have had a 24-inch diameter. The largest motor made in the UK was the Stonechat at 36-inch, but this would have been too heavy to use as a second stage. Larger diameter solid fuel motors were produced on an experimental basis at Westcott in the 1960s. Bristol Aerojet Ltd (BAJ) produced high strength steel tubes using the helical welding process, and Westcott developed the propellant charge design. Tubes up to 54 inches in diameter were produced, and one such tube was filled and fired at Westcott.4

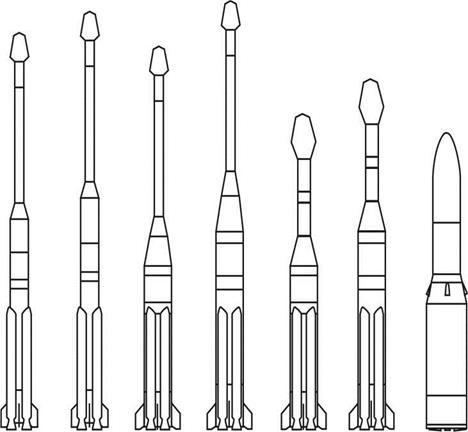

Fitting a 17-inch motor onto a 54-inch stage would have been awkward, but the bigger limitation would have been in the size of satellite carried. Even the smallest satellite would have been more than 17 inches across, and so an extremely bulbous fairing would have to be fitted on top. Even with a Kestrel, the geometry looks awkward, as the diagrams in Figure 121 demonstrate.

|

|

|

The Rook would seem to be better than the Kestrel on grounds of total impulse, but was less structurally efficient. On the other hand, there is no reason why two or even three Kestrels could be used – two Kestrels give nearly the same impulse as the Rook, they are structurally more efficient, and staging improves that efficiency.

In either case, the payload would be in the region of 200 lb or so – possibly more. In fact, the payload could be increased further: the total mass of the launcher would have been in the region of 29,000 lb or so, whereas the lift-off thrust was 75,000 lb. As mentioned, this gives the possibility of ‘stretching’ the Black Knight stage by lengthening the tanks to carry more fuel. By the time the boosters have burned out, the extra fuel will also have been burned off. This is quite efficient – the extra structural weight added is merely that of the thin walled tank.

Why is this a good deal cheaper than developing Black Arrow? There is very little in the way of development costs. By the time of the cancellation of the reentry experiments, BK26, the first 54-inch Black Knight, was quite well advanced in construction. The development costs of the Black Knight and the Kestrel would already have been absorbed by the re-entry programme. One of the major development costs for Black Arrow was the design and testing of the Gamma 8 and Gamma 2 motors. Developing more capable solid fuel motors is a good deal cheaper.

So, it might well have been possible to develop a Black Knight launcher costing not much than around £2 million which might have been able to put 200300 lb into orbit, compared with Black Arrow costing £10 million… and which could put around 150 lb into orbit.

1 TNA: PRO AVIA 65/1567. ELDO satellite launcher system.

2 Black Knight as a Satellite Launcher. AP Waterfall, Guided Weapons Department, RAE. 18 January 1961 (Science Museum Library and Archive).

3 Black Knight LOVER, Saunders Roe, May 1963.

4 Moore PO, 1992. Stonechat, JBIS, Vol 45, pp.145-148.

This page intentionally left blank

[1] R. Maudling. Memoirs. (1978). Sidgwick & Jackson Ltd.

2 The National Archives (TNA): Public Record Office (PRO) DEFE 7/2245.

Development of Blue Streak.

3 TNA: PRO DEFE 13/193. Development of Blue Streak missile.

4 TNA: PRO DEFE 7/2245. Development of Blue Streak.

5 Ibid.

6 TNA: PRO AVIA 92/24. Blue Streak: correspondence leading to the Cabinet decision to cancel as a weapons system.

[2] WJ Boyne, Clash of Wings. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994.

2 TNA: PRO AVIA 65/546. SR53 Finance and Policy. The details of the proposed improvements are outlined in a series of papers in this file.

3 TNA: PRO AVIA 65/287. F138D Saunders Roe rocket interceptor aircraft for RAF.

4 TNA: PRO BT 233/40.

5 TNA: PRO AVIA 65/649. Saro rocket interceptor: RN aircraft NA 47.

6 Ibid.

[3] TNA: PRO AVIA 65/91. Propelled air-to-surface missiles for ‘V’ class bombers: application to Vulcan aircraft.

2 TNA: PRO AVIA 65/1687. Blue Steel. Development programme.

3 TNA: PRO AVIA 65/91. Propelled air-to-surface missiles for ‘V’ class bombers: application to Vulcan aircraft.

4 TNA: PRO AVIA 65/1289 Blue Steel. Main propulsion unit.

5 TNA: PRO AVIA 65/1467 Blue Steel. Management Board.

6 TNA: PRO AVIA 65/1468 Blue Steel. RAE Study Group.

7 Ibid.

8 TNA: PRO AIR 20/12143. Proposals for OR 1149.

9 TNA: PRO AVIA 65/1697. Stand off bomb, OR 1159: research and development.

[4] TNA: PRO AIR 2/13206. ATOMIC (Code B, 12): Long range surface to surface weapons.

2 TNA: PRO AVIA 48/7. Rocket Research Panel: minutes of meetings.

3 TNA: PRO DEFE 7/2245. Development of Blue Streak. The Operational Requirement for a Medium Range Ballistic Missile system. Note by DCAS 9 August 1955.

4 TNA: PRO AVIA 65/1193. Warhead for a medium range missile: Air Staff requirement OR 1142 Orange Herald (DAW plans action). This file is the source for all the quotes in this section.

5 Ibid.

6 TNA: PRO AIR 2/13745. Warhead for medium range ballistic missile Blue Streak (OR 1139 and 1142).

7 TNA: PRO AIR 20/10299. Ballistic missiles: minutes of Joint US/UK Medium Range Ballistic Missile Advisory Committee and related papers.

8 TNA: PRO AVIA 6/17210. Application of solid propellant motors to medium range ballistic missiles. Technical Note RPD 156. WR Maxwell, December 1956.

9 TNA: PRO AVIA 54/2141. Blue Streak development: A1 Coordination Panel; minutes of meetings.

10 TNA: PRO AVIA 54/2146. Blue Streak development: Joint US/UK Advisory Committee; technical correspondence.

TNA: PRO DEFE 7/2245. Development of Blue Streak.

[5] TNA: PRO AVIA 68/23. Work supporting development of an underground launching system for Blue Streak. RPE Technical Note No. 170. BWA Ricketson and ETB Smith.

2 Ibid.

[6] was surprised and encouraged today that amongst those who are advising both the PM & the Chancellor there is a pronounced feeling that if we are to go on with the deterrent it should only be on the basis of Polaris.

[7] TNA: PRO AVIA 65/352. Space research vehicle design and performance: potential of reconnaissance satellites.

2 TNA: PRO DSIR 23/25364. Preliminary assessment of an earth satellite reconnaissance vehicle (RAE TN GW 393).

3 TNA: PRO AVIA 6/19852. Technical report G. W.455. The Use of Blue Streak with Black Knight in a Satellite Missile. D. G. King-Hele and Miss D. M. Gilmore. May, 1957.

4 TNA: PRO AIR 20/10573. Blue Streak: possible use as satellite launcher.

5 Science Museum Library and Archive

6 TNA: PRO AVIA 65/351. Space Research Vehicle Design and Performance: British Studies.

7 Saunders Roe Technical Publication 435.

8 TNA: PRO AVIA 66/4. Blue Streak as a satellite launcher.

9 TNA: PRO DEFE 7/1397. UK space research programme. 19 December 1960

10 RAE Communication Satellite Study. Working Party No. 2 meeting of 10 June 1963. (Science Museum Library and Archive)

[8] RAE Communication Satellite Study. Working Party No. 2 meeting of 17 June 1963. (Science Museum Library and Archive)

12 TNA: PRO AVIA 13/1351. Space policy: Black Arrow review 1967.

13 TNA: PRO DSIR 23/39853. Blue Streak/Centaur launcher.

1 TNA: PRO AVIA 66/4. Blue Streak as a satellite launcher.

Ibid. 3 Ibid.

Ibid.

5 TNA: PRO AVIA 65/1708. Blue Streak satellite launcher development: European cooperation.

6 TNA: PRO AVIA 66/7. Blue Streak satellite launcher project: Pt B.

7 Ibid.

8 TNA: PRO AVIA 65/1708. Blue Streak satellite launcher development: European cooperation.

9 TNA: PRO AVIA 66/4. Blue Streak as a satellite launcher.

10 Anglo-French technical proposals for the development of a satellite launching vehicle system / Propositions techniques Franco-Britanniques pour la mise au point d’un porteur de satellite; document elabore par le Ministere de l’aviation du Royaume-uni et le Ministere de l’air francais.

[10] TNA: PRO AVIA 66/8. Blue Streak satellite launcher project: Pt C.

Historical Archives of European Union, Florence, ELDO 118. Technical Definition of the Initial launching System. October 1963.

13 TNA: PRO EW 25/52. Review of UK space policy including European Launcher Development Organisation (ELDO).

14 Ibid.

15 HAEU, Florence, ELDO 828. Alternative Development Programme.

16 TNA: PRO T 225/2765. Ministry of Aviation space programme: future policy.

17 TNA: PRO EW 25/52. Review of UK space policy including European Launcher Development Organisation (ELDO). FR Barratt, 26 March 1965.

18 HAEU, Florence, ELDO archives.

19 TNA: PRO AVIA 92/259. UK withdrawal from European Launcher Development Organisation (ELDO).

20 Private communication.

21

Ibid. 23 Ibid.

[11] This is the mean thrust (in the original French ‘la pousee moyenne – 550 kN’ as opposed to ‘la pousee maximum – 630 kN’).

[12] to geostationary orbit

As can be seen from the figures for the estimated performance, the boosters produce a useful payload increase – but even 300 kg is distinctly inadequate for a

[13] HAEU, Florence, ELDO 80.

2 Design Studies On A High Energy Third Stage For The European Launch Vehicle. Dietrich Koelle, May 1963. (Private collection.)

3 TNA: PRO DSIR 23/31973. Flight trial of F1 of EUROPA 1 (ELDO satellite launcher system – first stage). RAE TM Space 45, August 1964.

4 HAEU, Florence, ELDO. F6/1 launch, September 1967.

5 HAEU, Florence, ELDO archives.

6 Ibid.

7 HAEU, Florence, ELDO 3569. E. L.D. O. B1 & B2 Vehicles Oxygen/Hydrogen Upper Stages. Rolls-Royce Thrust Chamber Design Study to E. L.D. O. Contract CTR/17/7/10. February 1967.

8 TNA: PRO AVIA 65/1567. ELDO satellite launcher system.

9 HAEU, Florence, ELDO 3515.

10 HAEU, Florence, ELDO 3035.

[14] HAEU, Florence, ELDO 1561. Low cost launchers – conclusions of the EUROPA II AD HOC group. 30 May 72.

12 HAEU, Florence, ELDO 4287. Europa IIIC with 4 RZ 2 engines.

[15] TNA: PRO AVIA 92/128. Policy and financial control of Westland Aircraft Ltd on Black Knight project,

2 TNA: PRO AVIA 48/58. Black Knight: trials. Preliminary Post Firing Meeting Friday October 3rd, 1958. Guided Weapons Department, RAE.

3 TNA: PRO AVIA 13/1268. ‘Black Knight’: hot tests on inertia navigator head. Summary of Direct Kinetic Heating Measurements on Black Knight, Dommett RL and Peattie IW. Guided Weapons Department RAE, 3 November 1961.

4 Interim Report on the Range Safety Proving Trial. Space Department, RAE. 2 January 1964. (Science Museum Library and Archive)

5 TNA: PRO DSIR 23/35658. Project dazzle Pt 5.

6 Minutes of a meeting at Osborne House 19 July 1962. (Science Museum Library and Archive.)

7 TNA: PRO AVIA 65/667. ‘Black Knight’ project: policy and financial control. PD Irons of Saunders Roe to WG Downey at the Ministry of Supply, 30 October 1958.

8 TNA: PRO T 225/2124. Space and general guided projectile research: Black Knight test vehicle; Ministry of Aviation firing programme. Memo by JA Marshall, 2 January 1961.

9 Ibid.

[16] If RAE had decided to go ahead with Crusade and the 54-inch Black Knight, but adapted as a launcher using solid motors as described earlier. Now let us imagine a timeline thus:

[17] If the French proposal for dropping ELDO A and going straight to ELDO B had won the day in 1965. One can sympathise to some extent with the Government’s position on ELDO, but again it lacked the courage of its own

[18] TNA: PRO AVIA 65/1851. WS-138A: Skybolt policy.

2 Ibid.

3 TNA: PRO DSIR 23/ 31835. Performance capability of Black Knight rocket in various roles (RAE TN Space 60).

[19] TNA: PRO AVIA 66/7. Blue Streak satellite launcher project: Pt B.

2 TNA: PRO CAB 129/127. Space Policy. Report by the Official Committee on Science and Technology. November 1966.