Blue Streak

1. The Government have been considering the future of the project of developing the long-range ballistic missile Blue Streak, and have been in touch with the Australian Government about it, in view of their interest in the joint project, and the operation of the Woomera range.

2. The technique of controlling ballistic missiles has rapidly advanced. The vulnerability of missiles launched from static sites, and the practicability of launching missiles of considerable range from mobile platforms, has now been established. In light of our military advice to this effect, and of the importance of reinforcing the effectiveness of the deterrent, we have concluded and the Australian

Government have fully accepted that we ought not to continue to develop, as a military weapon, a missile that can be leached only from a fixed site.

3. To-day our strategic nuclear force is an effective and significant contribution to the deterrent power of the free world. The Government do not intend to give up this independent contribution, and therefore some other vehicle in due course will be needed in place of Blue Streak to carry British-manufactured nuclear warheads. The need for this is not immediately urgent, since the effectiveness of the V-bomber force as the vehicle for these warheads will remain unimpaired for several years to come, nor is it possible at the moment to say with certainty which of several possibilities or combinations of them would technically be the most suitable. On present information, there appears much to be said for prolonging the effectiveness of the V-bombers by buying supplies of the airborne ballistic missile Skybolt which is being developed in the United States. H. M. Government understands that the United States Government will be favourably disposed to the purchase by the United Kingdom at the appropriate time of supplies of this vehicle.

4. The Government will now consider with the firms and other interests concerned, as a matter of urgency, whether the Blue Streak programme could be adapted for the development of a launcher for space satellites. A further statement will be made to the House as soon as possible.

5. This decision, of course, does not mean that the work at Woomera will be ended. On the contrary, there are many other projects for which the range is needed. We therefore expect that for some years to come, at least, there will be a substantial programme of work for that range.23

The Opposition based their first attack on the grounds of waste of large sums of public money, which Watkinson was able to counter with the argument that Blue Streak would be developed as a satellite launcher. It was a useful point for the Opposition to seize on, as it was an issue which could cover its own internal divisions about the deterrent.

But the satellite launcher option was a useful defence, indeed the only defence open to him, which raises the question: how genuine a statement was this? Did Watkinson and the Ministry of Defence really want a satellite launcher, or was this statement merely a political fig leaf? Given the enthusiasm (or lack thereof) with which the subsequent Cabinet committee greeted the topic, the suspicion is that the fig leaf is the correct answer. Certainly the initial reaction among those in the House was quite vigorous: George Brown was the then Shadow Defence Secretary, and demanded an immediate emergency debate, which, however, was not forthcoming. (Sandys’ absence from the House was noted by Jim Callaghan, who seized upon it to say: ‘I was commenting that it was a little unfair that the Minister of Defence should have to face all this music, and I was wondering where the Minister of Aviation is and when he is going to resign.’)

Given the costs of the project at the time of cancellation, the Opposition managed to force a later debate. Whilst Brown might have been a good speaker, what he said at the debate does not read well today. This is partly because, like all Opposition speakers in any debate, he had not had the Civil Service back up and briefings that Ministers have. It is also interesting to note that he seems to have had some inside information on ‘fixed sites’, but although he makes a great show of saying that he himself had advocated dropping the system, he sidesteps making any justification.

Although Watkinson, as Minister of Defence, opened the debate, Sandys was obviously the target for the Opposition. He gave a very straightforward speech in reply, even if he might not have been entirely convinced by his own side’s case. He was able to undercut Brown by resurrecting a quote from the time of Thor, when Brown had said that what the UK needed was its own missile with its own warhead, which is what Blue Streak had been. The other notable part about his speech is that, by Commons standards, it was not particularly partisan: he laid down the facts as he saw them, and did not attempt to make political capital from the decision.

But with the cancellation now official, interest within the Ministries of Defence and Aviation turned swiftly to Skybolt. The Navy was still not happy that Polaris had not triumphed, as can be seen from another internal Admiralty memo. It comments of Watkinson:

Skybolt lay ready to his hand (he thinks) as a blood transfusion to keep the V bombers effective from 1965-1970. … Our trouble is that the Minister has been advised by interested parties, in very optimistic terms, about Skybolt’s state and prospects. I would almost say that he has been led up the garden path. I would warn you that some of the advisers he will bring to you with him are bitterly anti-Navy.

It is ironic that 20 months later, in December 1962, Skybolt itself was cancelled by the US (as predicted by Brundrett and CGWL), and the UK had to negotiate hard to obtain Polaris. This meant that the ‘deterrent gap’ was now stretched to the late 1960s, and while the Polaris submarines were being built, the deterrent was being carried by V bombers with free fall bombs and the short range Blue Steel stand-off missile.

From the outset, the British Government had been warned that Skybolt was very much in the development stage, and there was no guarantee that it would actually be deployed by the USAF. The veteran Labour MP, Sydney Silverman, referred to Skybolt in the House of Commons in June 1960 thus:

Would it be a fair summary of what the right hon. Gentleman has told the House to

say that the result of his negotiations in the United States is that what he has really

done is to buy a pig in a poke with a blank cheque?

Whilst Silverman was making his attack mainly on party political grounds, there was more than a grain of truth in his comment.

Polaris did serve the UK well for nearly 30 years (although its mid-life upgrade, Chevaline, was also a source of controversy), and carrying the deterrent offshore leads to the argument that the mainland itself is no longer a target. Given however the number of NATO and US nuclear bases in the UK, that argument rather falls down. The cancellation of Blue Streak, and the reason given, meant that land-based missiles were never again an option for the UK deterrent. As to what purpose the UK deterrent was to serve, however, is another question.

The Powell report may have been ingenuous in its conclusions, but in the end, Blue Streak was indeed cancelled as a military weapon. Was this the right decision?

The answer to this can only be ‘yes’. Skybolt, had it been deployed, would have been almost as effective a deterrent for a good deal less money. Deterrents are there for political reasons: the whole point of them is that they should never be used! Britain’s deterrent was a perfect example – there was no way that it would be used without America becoming involved, and indeed that was one of the points of it.

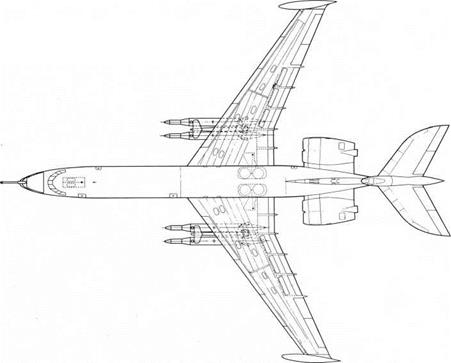

As to the vulnerability issues, the RAF was considering a follow on to the Vulcan as a Skybolt carrier – in the form of the Vickers VC10 airliner.24 This is not as absurd as it sounds: airliners are designed to stay in the air for long periods and to have very short turn round times. The point of Skybolt was that the carrier aircraft would not need to fly anywhere near the enemy defences – and so an airliner would have been an ideal vehicle for the purpose. Proposals were put forward for a system of standing patrols (not possible with the V bombers) using 42 modified VC10s.

As it turned out, Skybolt was cancelled and Britain was offered Polaris. The submarines were designed by the Admiralty, and the whole project was carried out exactly on schedule and within budget – an achievement that had eluded the Ministry of Supply for a decade (and is still eluding the Ministry of Defence today). Polaris served the country well in its function as a deterrent, staying in service until the mid-1990s.

|

Figure 53. Plan view of VC 10 airliner modified to carry four Skybolt missiles. |

Blue Streak, even in its silos, would have seemed outdated by around 1970, if not earlier. It would not have been difficult to have built and designed a substitute which was smaller and cheaper (warheads had become very much lighter in the interim), and which could also have been based in the same silos, but given the pace and cost of the project up to 1960, how much the silos would have cost, and when they would have been finished, is a very open question.

This may seem to be an extended exposition of the cancellation in what is, in the main, a book on the British rocketry programme, but it had a very considerable impact on the future of Blue Streak as a satellite launcher, and thus by extension, on any potential British space programme.

At the time of cancellation there was still a good deal of development work to be done on Blue Streak. If the missile had not been cancelled, then the cost of this would have fallen on the defence budget. Furthermore, there would have been a number of test and development launches needed at Woomera, and the facilities there would also have been charged to the defence budget. Building a launcher from a fully developed Blue Streak would have been relatively cheap. The upper stages would have been Black Knight derivatives, and the development of Black Knight itself had not cost a great deal. The major cost would have been in building the interface between Blue Streak and the upper stages (a further expense which would have been worthwhile would be the uprating of the RZ 2 motor from the 137,000 lb thrust for the missile to 150,000 lb – this would allow for heavier upper stages). Thus a quoted cost of £65 million for a Blue Streak satellite launcher in 1960 might have been reduced to a tenth of that by 1964, making such a launcher far more probable. What such a launcher might have been used for is the subject for later discussion!