Ion Motors

Ion motors are an extremely promising technology, and have remained mainly at the ‘extremely promising’ stage for the past 40 years. Instead of converting chemical energy into kinetic, as in conventional motors, it converts electrical energy into kinetic. This is done by ionising atoms, then accelerating them through a very large voltage. The main problem is that the only source of electrical energy in space (other than a nuclear reactor) comes from sunlight via solar panels. The amount of energy is not great, and thus the thrust available is small.

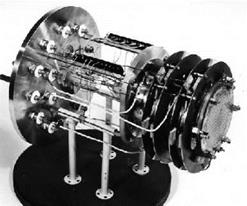

The RAE began investigating ion motors as early as 1963. Initial thoughts were for an attitude control and station-keeping capability. Another possibility emerged as a requirement for a high energy upper stage for the Black Arrow launcher, utilising the spiral orbit-raising principle from an initial low altitude parking orbit.

![]()

Interestingly, at that time ELDO was also considering the augmentation of the payload capability of its launch vehicle by the same means.

Interestingly, at that time ELDO was also considering the augmentation of the payload capability of its launch vehicle by the same means.

The initial designs used mercury: an ion accelerating

potential of about 1.5 kV was chosen, giving a S. I. of close to

3,0 s. The success of the initial

tests with the T1 thruster resulted in the design of a new device, the T2, for which a 10 cm beam diameter was selected to provide a thrust of 10 mN with a beam accelerating potential of 2 kV.10

10 mN thrust might be adequate for attitude control, but not for orbital adjustment. Further development has continued, with the main change being the substitution of xenon gas for mercury as the fuel, but the further story is rather beyond the scope of this book.

As a measure of the work being done by British firms on rocketry, the following figures were given in 1961 for the total expenditure to date (i. e., effectively, since the war):

|

£ in millions |

dates |

|

|

Napier: |

||

|

Double Scorpion de Havilland: |

1.486 |

1955-1959 |

|

Sprite & Super Sprite |

0.881 |

1947-1961 |

|

Spectre |

5.576 |

1953-1961 |

|

Research Bristol Siddeley Engines Ltd: |

0.254 |

1954- |

|

Snarler |

0.226 |

1946-1953 |

|

Screamer |

1.222 |

1946-1953 |

|

Stentor |

3.40 |

1956- |

|

PR.37/2 (Jindivik) |

0.029 |

1960- |

|

Gamma |

1.60 |

1956- |

|

Research |

0.39 |

1955- |

|

Rolls Royce: Blue Streak |

5.379 |

1954- |

|

Supply of HTP |

3.50 |

1946- |

These costings do not include the work done at RPE Westcott, which was considerable. The series of motors leading up to Gamma (Alpha and Beta) were developed there in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Rolls Royce used Westcott’s facilities for early RZ 2 work, and RPE also had its own on-going liquid hydrogen work. In addition, Westcott was a major centre for the development of solid fuel motors.

However, by 1968 the picture had changed radically. Napier no longer existed, de Havilland were doing no more work on rocket motors. Bristol Siddeley and Rolls Royce had been amalgamated. There was just the one firm, and work was shrinking. Val Cleaver, in charge of the rocketry work at Rolls Royce, wrote to the Ministry of Technology to ask how he could keep his team together:

In this atmosphere, it is hard to maintain staff morale, or to retain the good people. Many of our best men have gone out of rocket work over the years (apart from a few who have left our projects, only to emigrate to the States), and we have been able to justify the recruitment of only a mere handful of bright youngsters in recent years.

The Director General (Engineering) at the Ministry of Technology then wrote to CGWL to explain:

My object in encouraging Cleaver to write to you was the conviction that the presently foreseen programme of liquid rocketry development implies the winding up of Rolls Royce’s R&D activity in this field by the early seventies, and the facts need to be faced now, both by Mintech and by the Rolls Royce management.

He then went on to give the following figures for future planned expenditure, based on no further commitments to ELDO, one Black Arrow firing a year, and a limited programme on packaged propellants:

Year: 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971

Expenditure: 1.656 1.900 1.117 0.667 0.437

(in £ million)

It is not clear whether this includes work on the RZ 20 liquid hydrogen motor, which was being carried out under an ELDO contract (and part of the funding had come from Rolls Royce itself).

Indeed, one of Cleaver’s complaints was that it was all obsolescent technology. The RZ 2 had been designed in 1955, 13 years earlier, and although since refined, there was nothing further to be done with it. Similarly with the HTP work: all that was left was derivatives of the Gamma motor, which had started life again in the mid-1950s as the small chamber from the Stentor engine. The liquid hydrogen work was being run on a shoe string.

In the event, work effectively finished in 1971, with the demise of Black Arrow and of Europa. Since then there has been no significant rocketry work done in the UK.