How the ACV Works

An ACV is an aircraft only in the sense that it is lifted off the surface supported by the air beneath it. Air can exert a lot of power when it is under pressure, for example when it is blasted into an enclosed space. An ACV uses this power to lift itself, floating on a cushion of air created by powerful fans. In this way, it is able to move smoothly over land or water. An ACV cannot fly at height. Depending on the vehicle, the amount of lift is between 6 inches and 100 inches (15.2 centimeters and 254 centimeters).

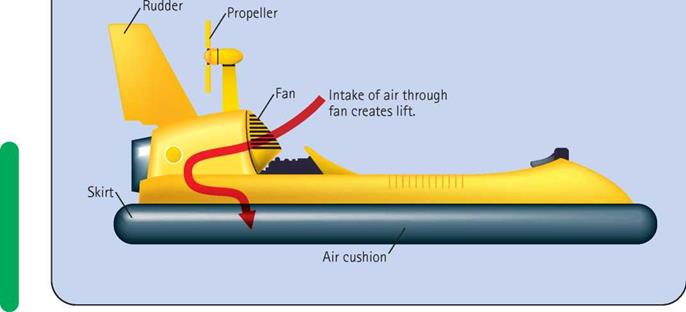

Some ACVs have wings, designed to generate just enough lift to raise the vehicle above the surface when it has reached a sufficient speed. Wings are not essential, however. An ACV will float on the compressed air that is sucked in by the fans and held in place beneath it. The air is contained either by a rigid sidewall or by a flexible skirt fixed around the lower edges of the vehicle. It is this air that gives the ACV its lift.

For forward propulsion, some ACVs use propellers turning in the air (like some airplanes). Others are driven forward by propellers turning underwater or by a high-powered water jet.

О This diagram shows the basic parts of a hovercraft. A fan sucks in air to create lift.

A propeller creates the thrust to move the craft forward, while a rudder is used to steer.

EXPERIMENTING WITH GROUND EFFECT

The principle of ground-effect flight was first suggested in 1716 by Swedish scientist and philosopher Emanuel Swedenborg. In the 1870s, British engineer Sir John Thornycroft experimented with model vehicles that floated on air.

He concluded that, instead of a ship having a conventional sealed hull, it could be designed with a plenum chamber-a box filled with air and open at the bottom. (A plenum is an enclosed space in which the air pressure is greater than the air pressure that surrounds the space.)

The air would reduce the drag from the water, allowing the ship to travel faster on less power. Unfortunately, the technology required to build a full-sized ACV did not exist at the time. In the 1920s, however, German engineers proved that a flying boat could achieve greater range and speed by flying very close to the water, making use of ground effect.

____________________________________________ /

ACV Pioneers

The modern ACV owes much to the pioneer work of three inventors: British engineer Christopher Cockerell and two Americans: airspace engineer Walter A. Crowley and U. S. Navy designer Colonel

Melville Beardsley. Cockerell had the idea that a vehicle would float on a ring-shaped curtain of air. He proved it with experiments using two empty coffee cans and a hair dryer. Crowley, meanwhile, was inspired by his discovery that a household lampshade could be made to float on air. In 1957 he built a hover-chair, which was not unlike a giant lampshade. He and Beardsley separately came up with the invention of a flexible skirt to stop air from escaping beneath the ACV. This escaped air had been the chief weakness of Cockerell’s design.

A skirt was fitted to the first practical ACV, Cockerell’s SR-N1 hovercraft. Big enough to carry three men, this vehicle crossed the English Channel in 1959. The SR-N1 skimmed across the sea at almost 30 miles per hour (48 kilometers per hour). It offered the prospect of an entirely new kind of ferry.