A SPACE SHUTTLE COPY?

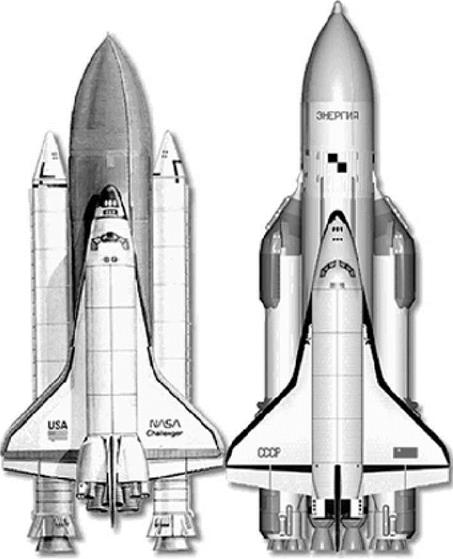

The unavoidable impression one gets when comparing drawings and pictures of the Space Shuttle and Energiya-Buran is that the Soviet vehicle is in many ways a copy of the American one. There were of course basic differences with the Space Shuttle, the most notable ones being the use of liquid vs. solid-fuel boosters, the placement of the cryogenic engines on the external tank rather than the orbiter, the use of cryogenic rather than hypergolic propellants for the orbiter’s orbital maneuvering and reaction control systems and Buran’s higher degree of automation.

However, there is no denying the fact that other differences between the two systems were in details rather than in fundamental design. The similarities far outnumbered the differences. The tank section of the core stage was a virtual carbon copy of the Shuttle’s External Tank and the orbiter was almost identical in layout, dimensions, and shape to its US counterpart. The similar dimensions were a logical result of the requirement to match the payload capacity of the Space Shuttle. As for the strikingly similar shape, when asked about this, Soviet officials usually responded along the lines that the laws of aerodynamics left little room for other designs. However, the dozens of orbiter outlines studied by NASA in the late 1960s and early 1970s and by the Russians themselves disprove this claim. In the end, Buran’s shape was largely determined by the very same Defense Department requirements that

|

Space Shuttle and Energiya-Buran compared (source: www. buran. ru). |

had forced NASA into the design for its Space Shuttle Orbiter (high cross-range capability and ability to transport large payloads). As one veteran admits:

“The deciding factor was not aerodynamics. We were in a position of having to play catch-up [with the Americans] … This is where the, unfortunately, classical opinion in our defense industry surfaced: the Americans aren’t dumber, do it the way they do!’’ [72].

Indeed, Buran was not the only example of following Western designs. Similar examples can be found in other branches of the Soviet industry as well, particularly in aviation. Among the more striking ones were the Tu-4 bomber, a clone of the B-29, and the Tu-144 “Konkordski”, the Soviet equivalent of Concorde. In some instances this was simply the fastest and most practical way of achieving parity, with the Russians apparently being not all too concerned about losing face in the process.

It should be pointed out though that Buran was the only obvious case of copying in the Soviet space program. While several Soviet manned and unmanned space projects were a response to American programs and intended to match their capabilities, the Russians usually came up with their own design solutions (e. g., Spiral vs. Dyna Soar and Almaz vs. the Manned Orbiting Laboratory). In the N-1/L-3 manned lunar-landing project, a program comparable in scale with Energiya-Buran, the Russians adopted the same Lunar Orbit Rendezvous technique as the Americans, but built a rocket that was fundamentally different from the Saturn V. Perhaps the negative experience with that project was one of the reasons that led them to more closely mimic the US design when the next program of comparable proportions came along. If things went wrong again, managers and designers would at least not be held accountable for “having done it differently than the Americans”.

More fundamentally though, this time around the Russians were not sure what the ultimate objectives of the American program where. Whereas the goal of Apollo unequivocally had been to put a man on the Moon, the motives behind the development of the Space Shuttle were much more nebulous from the Russian perspective. Fearing the military capabilities of the Shuttle, they felt it necessary to build an equivalent system, but, unsure of what exactly the threat was, they had little choice but to stick closely to the American design to make sure they would be able to respond to whatever strategic missions the Shuttle would eventually perform. Buran was built not out of some fundamental need in the Soviet space program, but as an answer to potential military and other applications of the Space Shuttle. This would eventually become the root cause of its downfall in the early 1990s.

By copying many aspects of the Space Shuttle design, the Russians could take advantage of the American experience, saving them a lot of research and development time. Although there is little evidence to support this, there can be little doubt that in designing their vehicle the Russians made use of the literature openly available on the Space Shuttle Orbiter. By the time the Energiya-Buran project got underway in 1976, the Shuttle’s design had been frozen for nearly two years and the first Orbiters were under construction. On the other hand, there is probably nothing fundamental that the Russians changed in their design based on actual US flight experience, because by the time Columbia flew STS-1 in April 1981 Buran’s own design had been finalized.

Still, the copying that irrefutably took place should not be used as an argument to belittle the Soviet accomplishment. No matter how much the Russians relied on Shuttle literature and blueprints, they still needed to develop the technology, the materials, and the infrastructure and do the testing all by themselves. Considering their overall less mature state of technology and the country’s smaller economic

potential, this was a remarkable feat, irrespective of whether the expenditures were justified or not.