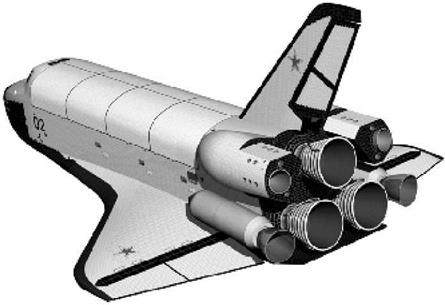

The OS-120 Shuttle copy

This was a virtual carbon copy of the US Space Shuttle, namely a delta-wing orbiter with three LOX/LH2 main engines in the back and strapped to the side of an external

|

The OS-120 orbiter (source: www. buran. ru). |

fuel tank. Sadovskiy’s team even went as far as studying the use of large solid-fuel rockets. Sadovskiy was no newcomer to solids, having earlier headed the development of two large solid-fuel nuclear missiles (the RT-1 and RT-2), the only such rockets ever built at the Korolyov bureau. This may even have been the very reason he was placed in charge of shuttle development at NPO Energiya.

However, the idea to use solids was abandoned because of the absence of the necessary industrial basis for the development of large solid-fuel rockets and the equipment to transport the loaded boosters to the launch site. Also, it would have been difficult to operate the boosters in the temperature extremes of Baykonur. Still, the idea to use solids was briefly reconsidered in the early 1980s as the RD-170 suffered serious development problems (see Chapter 6).

Instead, it was decided to use four 40.75 m high LOX/kerosene strap-ons, each powered by a single RD-123 engine. The orbiter itself would be fitted with three RD-0120 LOX/LH2 engines with a vacuum thrust of 250 tons. The orbital maneuvering system engines and reaction control system thrusters were arranged almost identically as on the US Orbiter (in two aft pods and a forward module) and would also use hypergolic propellants, the only difference being that the fuel on the Soviet vehicle would be dimethyl hydrazine rather than monomethyl hydrazine. The most striking novelty on the Soviet vehicle was the presence of two jettisonable 350-ton thrust solid-fuel escape motors on the aft fuselage that would have allowed it to instantly separate from the external tank in case of a launch accident.

The OS-120 orbiter owed its name to its 120-ton mass, which was the launch mass with a full 30-ton payload and minus the 35-ton emergency escape system, jettisoned

in the course of the launch. The overall launch mass of the stack would have been about 2,380 tons, almost 400 tons more than that of the Space Shuttle. In order to match the payload capacity of the Space Shuttle, the combined thrust of the engines was about 75 tons higher. This was also needed to compensate for the relatively high latitude of Baykonur (45°), where rockets benefit less from the Earth’s eastward rotation than they do from Cape Canaveral (28°). Had the OS-120 been launched from Cape Canaveral, it would have exceeded the Shuttle’s payload capacity by more than 5 tons for launches into 28° inclination orbits.

Being virtually identical to the Space Shuttle, the OS-120 inherited many of its drawbacks. While the LOX/kerosene engines of the strap-on boosters could be tested in flight on the 11K77 medium-lift rocket, the cryogenic engines were going to have to be tested with the priceless orbiter in place from the very first flight. With the spectacular N-1 failures still fresh in their memories, this was not an attractive idea to the Soviet planners. Therefore, they considered testing the engines in flight by mounting them on an unmanned payload canister replacing the orbiter (similar to the American Shuttle-C configuration), but this was a costly plan. The location of the main engines also shifted the vehicle’s center of gravity to the aft, imposing significant restrictions on the payloads it could carry and their distribution over the payload bay. It would also place higher acoustic loads on the orbiter, making it necessary to strengthen its structure, and also worsened the vehicle’s aerodynamic characteristics.

The OS-120 design also posed problems specific to the Soviet situation. If the engines were going to be on the orbiter, they would have to be made reusable, making their development even more challenging than it already was for an industry with very limited experience in cryogenic engine technology. Perhaps even more significantly, the orbiter would be so heavy that it could not be transported by any of the aircraft available at the time. The only aircraft capable of doing so, the Antonov design bureau’s An-124 “Ruslan”, was only on the drawing boards and years away from its first flight. Such an aircraft would also be needed for atmospheric drop tests, similar to the ones performed by NASA with Enterprise and a modified Boeing 747 [55].