PRELIMINARY STUDIES

Meanwhile, six Soviet military and civilian research institutes were tasked with performing a study of the Soviet Union’s future space transportation needs to help determine the need for a response to the Space Shuttle. These were TsNIIMash and NIITP (the Scientific Research Institute for Thermal Processes, the current Keldysh Research Centre) under MOM, TsAGI (the Central Aerohydrodynamics Institute) under MAP, TsNII-30 and TsNII-50 under the Ministry of Defense, and IKI (the Institute of Space Studies) under the Academy of Sciences. TsNIIMash was given the lead role.

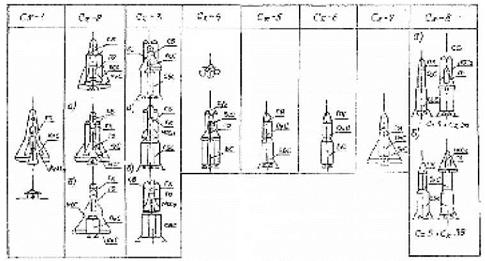

Actually, the studies centered not solely on shuttles, but on a wide array of expendable and reusable launch vehicles that would provide the most economical access to space in the future. They also extended to various reusable space tugs and expendable upper stages with either liquid or nuclear rocket engines for interorbital maneuvers and deep-space missions. Four future directions were considered for the Soviet Union’s space transportation program:

• the continued use of expendable launch vehicles and spacecraft until the year 2000;

• the continued use of expendable launch vehicles, but with standardized satellites;

• the use of a reusable space transportation system capable of returning spacecraft back to Earth for servicing and subsequent reuse;

|

Reusable space transportation systems studied at Soviet research institutes in the early 1970s (source: Ts. Solovyov). |

• the use of a reusable space transportation system capable of servicing and

repairing satellites in orbit.

As for reusable systems, the institutes explored two vehicle sizes, one able to accommodate payloads of 30-40 tons (like the Space Shuttle) and another for payloads weighing 3-5 tons. Furthermore, two ways were studied of recovering the first stage, one involving the use of standard recovery techniques, the other requiring the use of reusable flyback boosters.

The six institutes presented their joint findings in June 1974. They concluded that the development of a reusable launch vehicle was only economically justified if the launch rate was very high, more particularly if the annual amount of cargo delivered to orbit would exceed 10,000 tons. However, it was stressed that much also depended on the vehicle’s capability of servicing satellites in orbit or returning them to Earth for repairs. The size of the spaceplane in itself would not determine its effectiveness and would have to depend on the mass and size of the payloads that needed to be launched or returned. Finally, it was recommended to perfect future reusable systems by developing first stages with air-breathing engines and eventually to introduce high-thrust nuclear engines for single-stage-to-orbit spaceplanes.

Basically, the conclusion was that a Space Shuttle type transportation system would not provide any major cost savings even if a relatively high launch rate was achieved and should be seen as nothing more than a first step towards developing more efficient transportation systems. However, the consensus was that if a reusable system were developed, preference should be given to a big shuttle akin to the American one [4].

On 27 December 1973, without awaiting the results of the studies, the VPK ordered three design bureaus to formulate so-called “technical proposals” for a reusable space transportation system. This is one of the first stages in a Soviet space project, in which various preliminary designs are worked out and compared in terms of their technical and economic feasibility. While the VPK order was significant in being the first official government-level decision on a Space Shuttle response, it was far from a commitment to build such a system, but merely an attempt to explore various vehicle configurations that might eventually lead to to a final decision later on. The three bureaus were MMZ Zenit (headed by Rostislav Belyakov after Mikoyan’s death in 1971), Chelomey’s TsKBM, and Mishin’s TsKBEM. They came up with two basically different concepts that reflected the conflict between a small vs. a large shuttle.

MMZ Zenit was best prepared to respond to this order, having worked since 1966 on its Spiral air-launched spaceplane and benefiting from actual suborbital flight experience with the BOR-1, 2, and 3 scale models. Strictly speaking, the space branch that had been set up in Dubna in 1967 to work on Spiral was no longer subordinate to MMZ Zenit, having merged in 1972 with MKB Raduga (another former branch of Mikoyan’s bureau) to form DPKO Raduga. The VPK order must have been a major morale booster for Lozino-Lozinskiy’s Spiral team, which because of a lack of government and military support had been forced to do its work on an almost semi-legal basis. It did require the team to divert its attention from the small air – launched Spiral, which had been primarily designed for reconnaissance, inspection, and combat missions. With the focus now shifting to transportation tasks, a larger version of Spiral with a higher payload capacity was needed. Although the details are sketchy, Lozino-Lozinskiy’s team seems to have studied an enlarged 20-ton version of the Spiral spaceplane launched by the Proton rocket.

TsKBM also set its sights on a 20-ton spaceplane to be orbited by the Proton, which itself was a product of Chelomey’s bureau. However, the spaceplane project seems to have been low on Chelomey’s list of priorities at this stage. Indications are that the bulk of spaceplane research at TsKBM was done in the late 1970s, by which time Buran had already been approved (see Chapter 9) [5].

TsKBEM was to focus on a Space Shuttle sized vehicle to be orbited by the N-1 rocket, but it appears that little, if any, work was done on this. The research was to be done by a small team headed by Valeriy Burdakov, but as Burdakov later recalled, the team’s work was limited to studying the possibility of reusing the first stage of the N-1 and keeping track of foreign literature on reusable space systems [6]. However, big changes were ahead at TsKBEM that would turn these plans upside down.